1961 Ferrari 156 F1

Photo: Archives Trips

Icon is probably an over-used word in automotive journalism, and modern commercialism has seen it applied to many automobiles which are clearly not icons – and sometimes not even interesting. However, it is difficult indeed to find a more fitting term to describe the Ferrari 156 – the “Sharknose” – a Grand Prix car which dominated its championship season in 1961 and just as quickly faded away the following year. While the car itself was hardly revolutionary, it came at a key moment in Grand Prix racing, and it was at its peak when a whole collection of great racing drivers were also at their peaks. It was a car for a time, and the time was a remarkable one in racing history.

Where did the Ferrari “Sharknose” come from? This question has several possible answers: one relates to Ferrari’s long-term traditions and design philosophies; one in relation to the changes which took place in motor sport at the time; and at least one related to the people who worked at Ferrari in 1960, most notably Carlo Chiti.

One long-standing tradition at Ferrari was to concentrate on what Enzo Ferrari considered to be the heart of the car, the engine. Enzo Ferrari was sometimes viewed as being almost obsessed with engine rather than chassis development. Indeed, the company produced some of the finest road and racing engines of all time.

In 1958, the CSI governing body announced that starting in 1961, all Grand Prix races would be run to a 1.5-liter formula. While many manufacturers believed this would never happen, the seeds for the future had indeed been firmly planted. As late as 1959, Enzo Ferrari announced he had no plans for a rear-engine Grand Prix car, but within a very short time, Carlo Chiti – then senior competition engineer – announced that he had a rudimentary chassis on the workbench. He intended to try this new chassis out with the 65-degree engine, but also had a more potent 120-degree engine in the design stage. Both of these engines would become the “heart” of the “Sharknose.”

First tests of the rear-engine car took place in 1960 with a 2.4-liter version of the Dino engine. In 1960, American Richie Ginther gave the chassis its first race at the Monaco Grand Prix with the larger engine, and finished sixth, but many laps down. In July, Wolfgang von Trips drove the same chassis with the 1.5-liter unit in an F2 race at Solitude, near Stuttgart. In the wet, von Trips took the somewhat ungainly looking car into the lead and went on to win. As a result, Ferrari then gave Chiti a free hand to design rear-engine sports and Grand Prix cars and finally accepted that the front-engine racecar was dead. Some interpretations of this shift in design philosophy have tended to view this changeover as sudden and enlightening. However, it was far more likely that wily Enzo had gotten the message from the early success of the Coopers and had been working away to produce an engine that would clean up under the new rules in 1961.

First Success

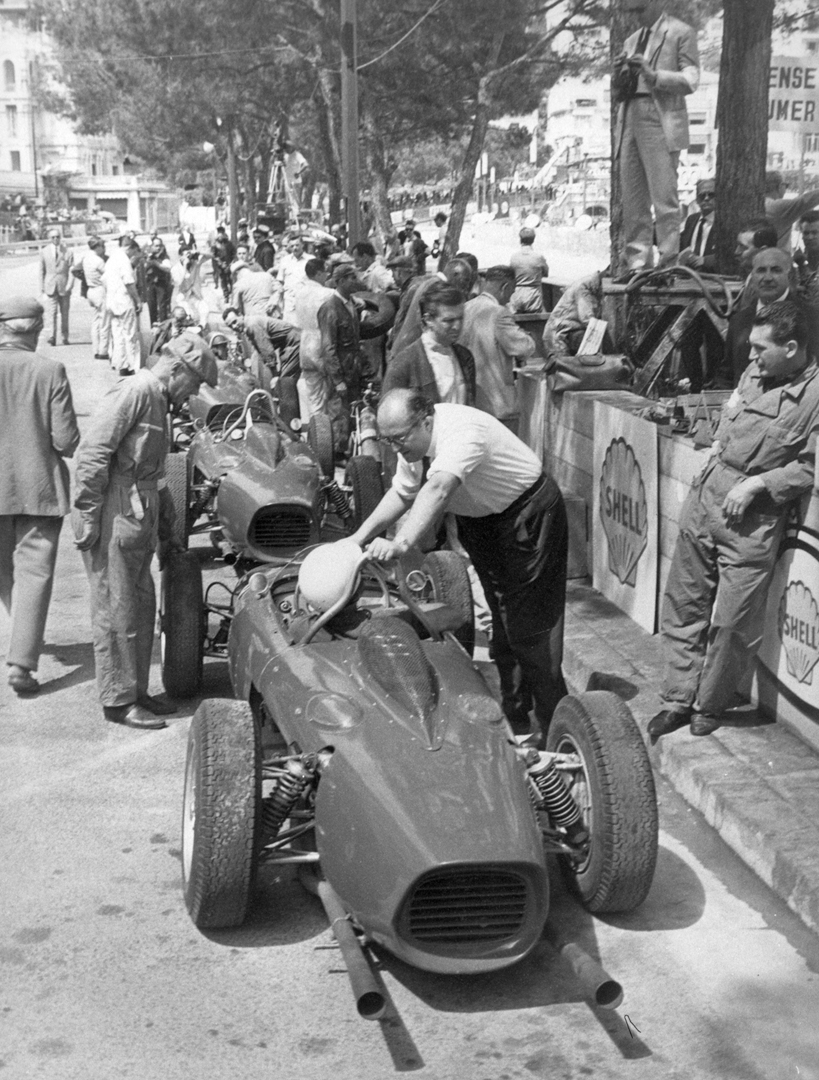

Photo: Julius Weitman

As was the custom of the time, 1961 opened with a number of nonchampionship Formula One races, and these were run to the new 1.5-liter regulations. Ferrari entered none of these events until April, when the relatively unknown Giancarlo Baghetti was entered in a Dino 156 for the Siracusa Grand Prix in Sicily. However, the chassis which von Trips had been successful with in 1960, had now been refined and carried a stunning new body – elegant, elongated and adorned with a nostril-like nose. It wasn’t long before this new design was dubbed the “Sharknose” – an icon had been born. Something about that shape enclosing the new chassis and beautiful sounding V-6 caught the imagination of racing fans immediately. It became the symbol of motor racing for that period.

While stunningly beautiful, the “Sharknose” design wasn’t entirely new. Journalist and Ferrari expert Hans Tanner claimed the original concept was the idea of Medardo Fantuzzi who had tried a twin nostril approach on the “piccolo” Maserati 250F. The French Sacha Gordine also utilized a similar treatment in the early 1950s. In the case of the 156, model-maker Casoli produced the first model for the body and was working on a parallel treatment for the sports cars at the same time. However, it is virtually impossible to determine exactly when the body made its first appearance on the car. Phil Hill couldn’t remember seeing it before the Siracusa race, and there was virtually no testing of the 156 with the new body. The car, of course, made a dream debut, and Baghetti won from Dan Gurney’s Porsche to give the “Sharknose” and himself maiden F1 wins.

Photo: Brian Joscelyne

Understandably, Baghetti’s victory sent a chill through the other teams. The British F1 establishment, which had been hedging its bets and was hoping that the 2.5-liter Intercontinental Formula might rival the new 1.5-liter Formula, soon saw the writing on the wall. If an unknown driver could win with a brand new car, what would happen when the aces got in it? And these aces were Phil Hill, von Trips and Ginther, all known quality drivers.

In reality, it wasn’t really a brand new car, it was more a serious refinement of the 1960 F2 machine, with Chiti working away at making the engine more powerful, while simultaneously developing the 120-degree variant. The 156 chassis followed the general lines of the F2 car, but there were also many differences. The front wishbones were forged, while the rears were of welded tube construction, and the chassis frame was of large diameter tubing – more like a Cooper than a Lotus. The space frame had the engine behind the driver with a 5-speed gearbox on the end of which was mounted the flywheel and clutch. The drive from the engine passed through the gearbox/differential housing to the clutch and back into the gearbox. A 12-volt battery was carried at the front of the chassis behind the oil tank, and both of these were mounted behind the radiator and above the rack and pinion steering mechanism. The radiator, of course, was housed inside the shapely new nose – menacing and, at the same time, beautiful.

Photo: Ferrari

The car’s short steering column passed through a chassis member and was carried in a bearing mounted behind the instrument panel. The fuel tanks formed the cockpit sides, and there was a well-padded seat and pads on the chassis to support and cushion the drivers’ shoulders. A 10,000 rpm tachometer faced the driver with a gear gate on the right and a curved Perspex screen, which wrapped around both sides of the body. To counter the look of the long nose, the rear of the body was finished in a blunter shape with slats in the rear. Through 1961 and 1962, however, there were variations on the length and shape of both the front and rear. The car carried front and rear disc brakes, the rear inboard mounted and the fronts hub mounted. Borrani wire wheels completed the package.

The 1961 World Championship

While the highlights of the 1961 Grand Prix season have been well documented, much less has been reported about how the team worked, how the very human characters of the time got on with each other, and how Ferrari’s drivers got along with the man himself. While Phil Hill has a great recollection of 1961, he remains hesitant about talking in evaluative terms about his fellow drivers and other team members. One thing is for sure, Enzo Ferrari was not easy to work for. He was arrogant and demanding, and Carlo Chiti’s contribution to the Championship in 1961 is often overshadowed.

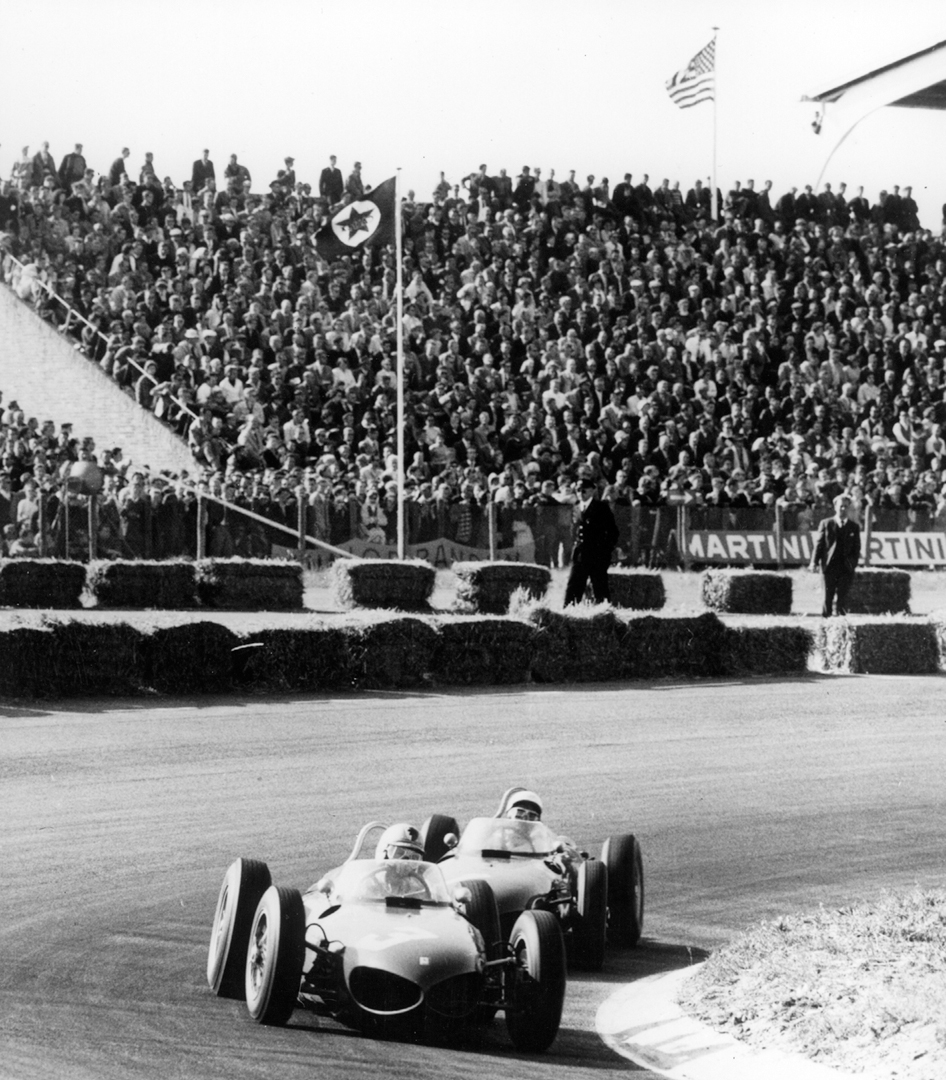

The cars weren’t as great as they may have seemed either. The chassis was reasonable but not nearly as nimble as Stirling Moss’s year-old Rob Walker-entered Lotus 18-Climax. At the first championship Grand Prix in Monaco, Moss drove one of his greatest and hardest races to defeat the three “Sharknose” cars from Modena. Ginther, in the 120-degree-engined car, gave the best chase to Moss and finished a very close second with Phil Hill third. This was a race between the two Ferraris and Moss… no one else really got a look in. Trips was a distant fourth. Ginther, who did and would continue to do most of the development work on the car, said the handling couldn’t match the Lotus, though the engine was brilliant.

Photo: J.T. Fodisch

On the same day as Monaco, Baghetti managed his second F1 win in another nonchampionship round at Naples, where all those who didn’t get invited to Monaco had gathered.

Three Ferraris were sent to Zandvoort for the Dutch Grand Prix, all with the quicker and more flexible 120-degree engine. Phil Hill thought that Zandvoort would suit the chassis characteristics of the car, and he was right; but it was von Trips who won from Hill in a dominant manner, becoming the first German to win a modern Grand Prix. This race was also noteworthy in that it was the only one in which not one car visited the pits.

In mid-June, Hill led a crushing Ferrari attack at Spa in Belgium, ahead of von Trips, Ginther and Belgian Olivier Gendebien, whose car was painted in yellow Belgian colors for the race. Two weeks later, another milestone took place at the flat-out circuit of Rheims in France when Baghetti, brought up for his championship debut, outlasted his teammates and became the first ever driver to win his first Grand Prix. Phil Hill had been in control when he had a controversial coming together with Stirling Moss. Hill claims Moss pushed him into a spin, and Moss says Hill spun and he then hit him! Hill finished well down after push starting the car, but this race had also seen the first retirement of a “Sharknose.”

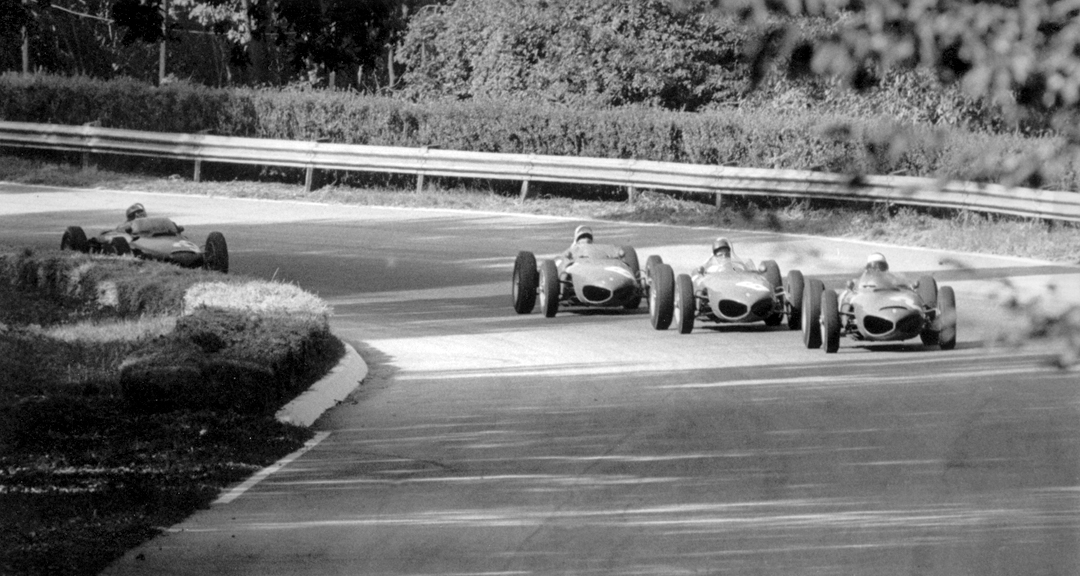

Photo: Brian Joscelyn

Von Trips took the British GP at Aintree, and then Moss had perhaps the other of his “great races” when he beat von Trips and Hill at the Nurburgring. All this time there was no mention of team orders, and tension was rising in the Ferrari camp as Hill and von Trips remained close for the world title. Then came Monza and the Italian Grand Prix.

The three regular drivers were joined by Mexican new-boy Ricardo Rodriguez, who became the youngest Grand Prix debutant ever. After two days in the car, Rodriguez put it on the front row alongside von Trips. This result didn’t harm the iconic legend of the “Sharknose” one bit, but that year’s Monza race is remembered almost entirely for von Trips’ crash, which killed him and 14 spectators as the championship-conscious German fought to defend his position from an attacking Jim Clark. The two touched and von Trips went up the banking in one of racing’s great tragedies. The “Sharknose” was beautiful, but now it was “lethal.”

And that was, basically, the end. Hill won the World Championship, deservedly after a season of brilliant driving. Ferrari didn’t go to the US Grand Prix, and an internal battle saw Chiti and several other senior personnel at Ferrari leave or be fired, depending on which version you choose to believe. Hill, Bandini, Mairesse, Rodriguez and Baghetti all drove in 1962. But by then Lotus and BRM had caught up, and the “Sharknose” had very little further development in spite of the efforts by engineer Mauro Forghieri. The chassis was good on tight circuits but wouldn’t work on the quick ones. Despite some good results for the “Sharknose,” it was Graham Hill who took his BRM to the title in 1962. Interestingly, Stirling Moss would have been one of the team drivers to race the “Sharknose” in 1962, if his horrific Goodwood crash hadn’t prematurely ended his career.

Photo: G. Molter

Driving the Sharknose

In spite of the efforts of rock musician Chris Rea to re-create a Ferrari 156 in recent years, no “real” cars have survived. So there has been no opportunity to track test this piece of history. The general belief has always been that none of the cars survived Ferrari’s custom of destroying or cannibalizing old Grand Prix cars. In spite of occaisional rumors to the contrary, the experts have tended to agree that no examples of the “Sharknose” remain. The immediate future may spring a surprise or two, but at this stage we can only talk about driving the “Sharknose” through the experience of the only survivors of the period. Cliff Allison tested the car in its pre-Sharknose state, and of course, 1961 World Champion Phil Hill took his title in it.

While the interview which accompanies this article goes into further detail, Hill was very impressed with the rear-engine format from the beginning, being most struck by how much difference the positioning of the driver changed the whole approach to racing – especially the handling of the car. He confirms that the chassis was nothing special but had undergone some reasonable development in 1961, in spite of a very limited testing program. However, Chiti continually improved the torque and flexibility of the engine; and even though the Lotus was nimbler, the Ferrari engine/gearbox/chassis combination managed to dominate in 1961.

Photo: Archive Trips

The “Sharknose’s” braking was always superlative, as the balance of the car was so well sorted out. In 1962, however, the chassis was improved in only minor fashion, and the layout of the clutch and gearbox became a particular weakness according to Hill. The other issue, of course, was that not all the team cars were the same in either 1961 and 1962, and at times, two identical chassis would produce very different handling characteristics. The engine, however, hardly ever missed a beat and there was rarely an engine failure. The body layout remained essentially the same through the two years, with the shape changing in minor ways, until in 1962 Lorenzo Bandini appeared in a new 156 with the distinctive “nostril-nose.” The modern Grand Prix shape had appeared, and the next season the V-8 would replace the V-6. As fast as it burst on to the international scene, the 156 “Sharknose” disappeared into obscurity.

Some of the material in this article has been extracted from Ed McDonough’s new book, “Ferrari 156:Sharknose” which will be available from Sutton Publishing in late August.

Specifications

Chassis: Multiple tube, spaceframe.

Bodywork: Hammer-formed aluminum.

Front suspension: Double arm wishbones with coil springs.

Rear suspension: Double arm wishbones with coil springs.

Front track: 1961: 3’ 11”. 1962: 4’ 1″

Rear track: 1961: 3’ 11”. 1962: 4’ 1″

Wheelbase: 7’ 7″

Engine type: Dohc, aluminum V-6.

Capacity: 1476cc

Bore & stroke: 73 x 58.8 mm

Horsepower: 65-degree: 180bhp. 120-degree: 190bhp

Max. RPM: 65-degree: 9000. 120-degree: 9500

Carburetors: 3 Weber twin choke

Gearbox: 5-speed

Brakes: Dunlop disc brakes

Wheels: Borrani wire

Resources

McDonough, E.

Ferrari 156: Sharknose

Sutton Publishing, 2001

Gloucestershire, UK

Motorsport

June, 1961

Tanner, H. and D.Nye

Ferrari (6th Edition)

Haynes Publishing, 1984

Somerset, UK

Bloodlines: Ferrari 360 Spyder

For power, the 360 benefits from an all-aluminum alloy, 3.6-liter dohc V8, with 5-valves per cylinder, variable valve timing, fly-by-wire throttle and a variable geometry intake manifold that can alter the length of the induction system for maximum efficiency at all engine speeds. This sophisticated powerplant knocks out an amazing 400 bhp at 8500 rpm. Couple this engine with Ferrari’s F1-developed six-speed electro-hydraulically controlled semi-automatic gearbox and you have a lightning-fast car capable of going from 0-60 in under 4.5 seconds, with a top speed of over 180 mph. If one can find any fault with this impressive combination, it is perhaps the engine note, which has lost that characteristic throaty Ferrari growl found on earlier cars.

Interior features are somewhat minimalist by Ferrari standards, but nicely finished with very comfortable, power-adjustable, leather-covered sport seats and one of the nicest air-bag equipped steering wheels of all time. One of the most impressive comfort features is the fully automatic soft top, which opens and is stored away under its own tonneau in 20 seconds.

There is no question that the 360 Spyder is a fabulous car and a technological tour de force for Ferrari. However, for the dyed-in-the-wool racer, it may be almost too good. Some very experienced drivers have commented that the 360 is so good that it has removed some of the challenge (and fun) out of high-speed driving. For those who still relish their string-back driving gloves, we might suggest you consider a 360 with available manual trasmission. Regardless of which gearbox you prefer, you will certainly be impressed with Ferrari’s F1 car for the road.

Reviewed by Casey Annis