On New Year’s Eve in 1950, the first endurance race run at Sebring was won by a very unlikely car, a car with an engine that displaced just 44 cubic inches, put out 26.5 horsepower, and had only been entered the day before the 6-hour race was held. It was a Crosley Hotshot, and it took the overall win in a way that has likely not been repeated since.

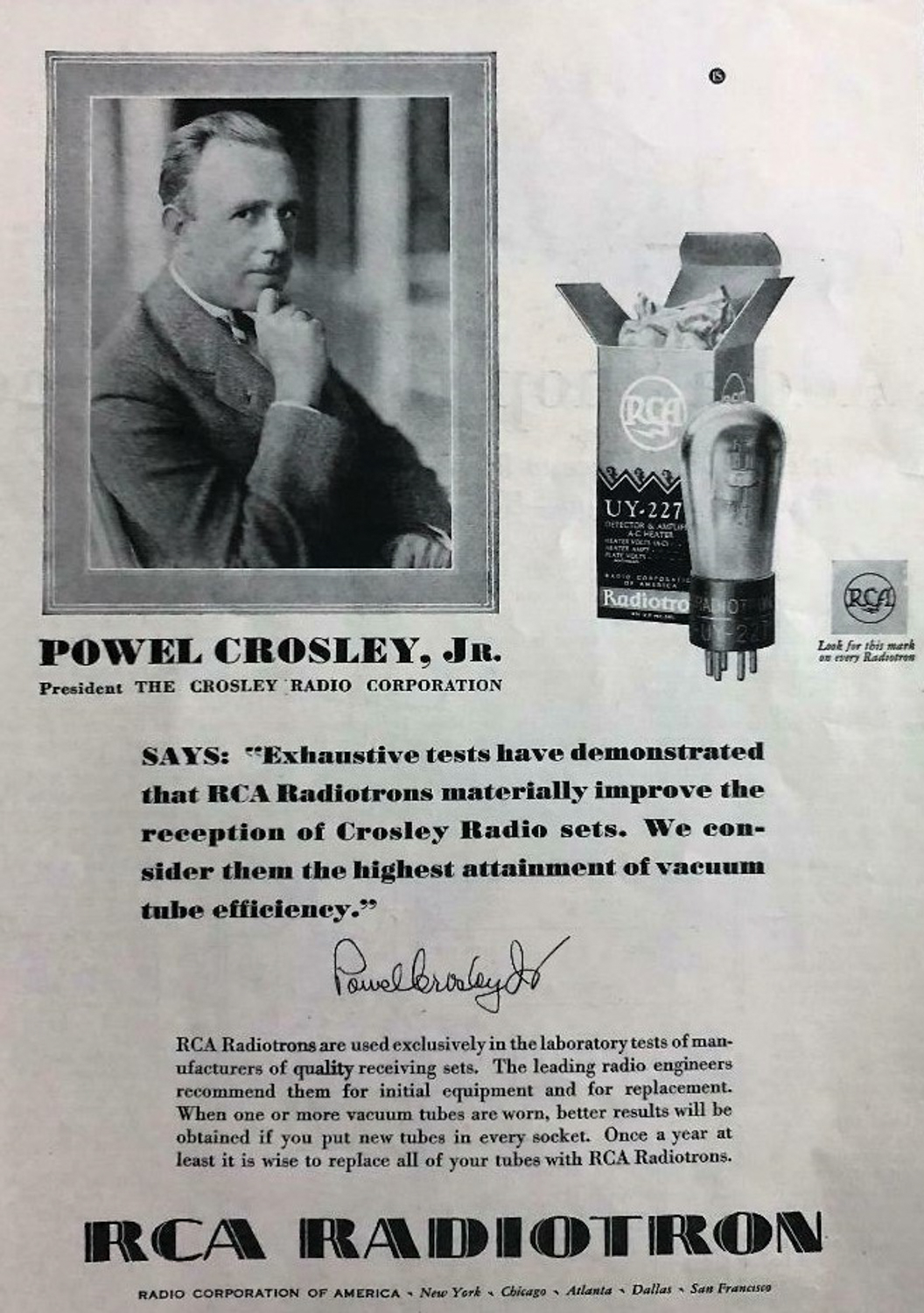

Powel Crosley, Jr. and His Radios, Refrigerators, and Cars

Powel Crosley, Jr. is best known for his radios, next best for his refrigerators and other appliances, and least well known for his automobiles. It was his interest in automobiles, though, that first drove him to become a manufacturer. Crosley was12, in 1898, when he first decided that automobiles represented the future. He also decided to build one and borrowed $8 from his younger brother, Lewis, to make it happen. Together, the brothers bought the parts needed to install an electric motor, drive chain, and steering to an abandoned buckboard wagon to see if they could turn it into a self-propelled vehicle. Impressed with his sons’ efforts, Powel Crosley, Sr. offered the boys $10 if they could make their contraption move under its own power. It did – for a city block. Powel paid back his brother’s loan, and the two split the $2 profit. With that success, Powel Crosley decided he would become an automobile manufacturer. According to Michael Banks (“Crosley and Crosley Motors”), Lewis Crosley often said about his brother, “The only reason he became rich was so he could build automobiles.” It would take many years, with numerous missteps, but Crosley eventually did become an automobile manufacturer.

Crosley dropped out of college, in 1906, after trying engineering and law as majors. He sold municipal bonds for a short time before launching his first attempt at producing an automobile. He had been developing plans for the Marathon Six for some time. He intended it to sell at the low end of the luxury market, at $1700. He managed to convince investors to provide $10,000, and he opened the Marathon Six Automobile Company in Connersville, Indiana, in the summer of 1907. It would be an assembled car – all the components coming from other manufacturers – and have a wheelbase of 114”. A prototype was built and shown, and orders were taken, but Crosley was soon out of money, and the Panic of 1907 meant no investors were willing to help him. When the economy improved, Crosley was again looking for investors and having success. He raised $30,000, and the Marathon Motor Car Company was incorporated in February 1909 in Cincinnati, Ohio. Apparently, though, Crosley’s investors wanted to be actively involved in the company, something Crosley found oppressive. Three months after the company started production, Crosley left for Indianapolis, Indiana, where he spent several months working for other automobile companies. He returned to Cincinnati in the winter of 1909, but he did not rejoin Marathon and instead worked for a competitor, then ran a new car dealership for a few years.

The next automobile Crosley conceived was the six-cylinder Hermes. His Hermes Motor Car Company was incorporated in December 1912. The car was called the Hermes 6-50 for its six cylinders and 50 horsepower. It included some innovations, such as an electric starter, battery-powered headlights, and wire wheels. However, Crosley’s timing proved, once again, to be unfortunate. He needed money for production of the Hermes, but the country fell into a recession, and his company failed. His next misadventure was in the cyclecar market. Crosley incorporated the DeCross Cyclecar Company in October 1913. The company’s motto was “For the Masses, Not the Classes,” but the cyclecar market was already overloaded with competition and, together with the falling prices of cars like the Ford Model T, this venture was also a failure.

Crosley’s first real successes came from sales of automobile accessories. Some of the accessories were of questionable quality and usefulness, such as an additive called “Gaso-Tonic” that did little to help engines run better. And there was the “Little Friend,” a gadget that allowed the engine to “burn free air,” and the “Booster,” an auxiliary water carburetor. He did have some legitimate products which he was able to patent. The “Litl Sho-Fur” was a clever device that caused the front wheels of a Model T to return to straight forward after the car suffered a bump that put the wheels out of alignment. Another development was the “Insyde Tyres.” This allowed a car owner to put a worn out tire carcass inside a new tire making it less susceptible to having a flat. Crosley became the sole owner of the American Automobile Accessories Company in 1917, and was very successful in selling the products he had developed, as well as tools, wax, spark plugs, and other car parts and accessories.

During the “War to End All Wars,” Crosley’s company produced military supplies to support the American troops fighting in Europe. It was after WWI that Crosley found his true place in the American economy. Lewis Crosley, now a degreed engineer, joined his brother and took over daily operations of the company, which was a good move since Powel Crosley was much more of an idea man than a manager. The company took a new direction with the creation of a division called the Crosley Manufacturing Company, created to produce non-automotive parts, including a phonograph. Many of the products the new division built were wholesaled to Sears Roebuck and Company. But it was a request from Crosley’s son that launched his father’s business into a national and international giant. In 1921, Crosley’s son asked his father for a radio receiver. Crosley discovered that those available were quite pricey, so he and his son built a radio. Crosley found that he could build radios at a fraction of the cost of those available at the time.

Over the next few years, Crosley launched the Crosley Radio Corporation, established his own radio station, WLW, and produced the second automobile radio, the “Roamio.” The Crosley Radio Corporation was soon the largest radio manufacturer in the world, and WLW became the world’s most powerful radio station. Crosley took his corporation public in 1928, and he and the company prospered. Crosley amassed a large fortune, bought mansions and retreats, acquired controlling interest in the Cincinnati Reds baseball team, and diversified into home appliances. He even tried airplane manufacturing, but he quit before any planes went into regular production. Crosley was still interested in gadgets and produced quite a few, even some, like the “Xervac” hair growing machine, that were clearly scams.

Among Crosley’s toys were a number of automobiles, from Fords to Duesenbergs, but he also had an American Austin, which he used at an estate in Florida. Crosley had long been interested in small cars, and the success of his appliance company allowed him to re-enter the automobile manufacturing business. He created the Crosley Radio Automotive Division (CRAD) in order to bring his small car vision into reality. While Americans appeared to like large, fast cars, Crosley believed there was a market for a small, economical automobile in America. Initially, his concept for his CRAD automobile was for it to have three wheels and an air-cooled two-cylinder engine, have room for four adults, and be cheaper than anything else being sold. Eventually, the three-wheel concept was dropped for a four-wheel car, although with the rear wheels only 18” apart. The intent was for there to be pleasure and delivery versions of the CRAD, but ultimately there were two designs penned by a draftsman at the Murray Body Company, who would build the actual bodies. They were a slope-backed coupe and a pickup truck, both with canvas tops.

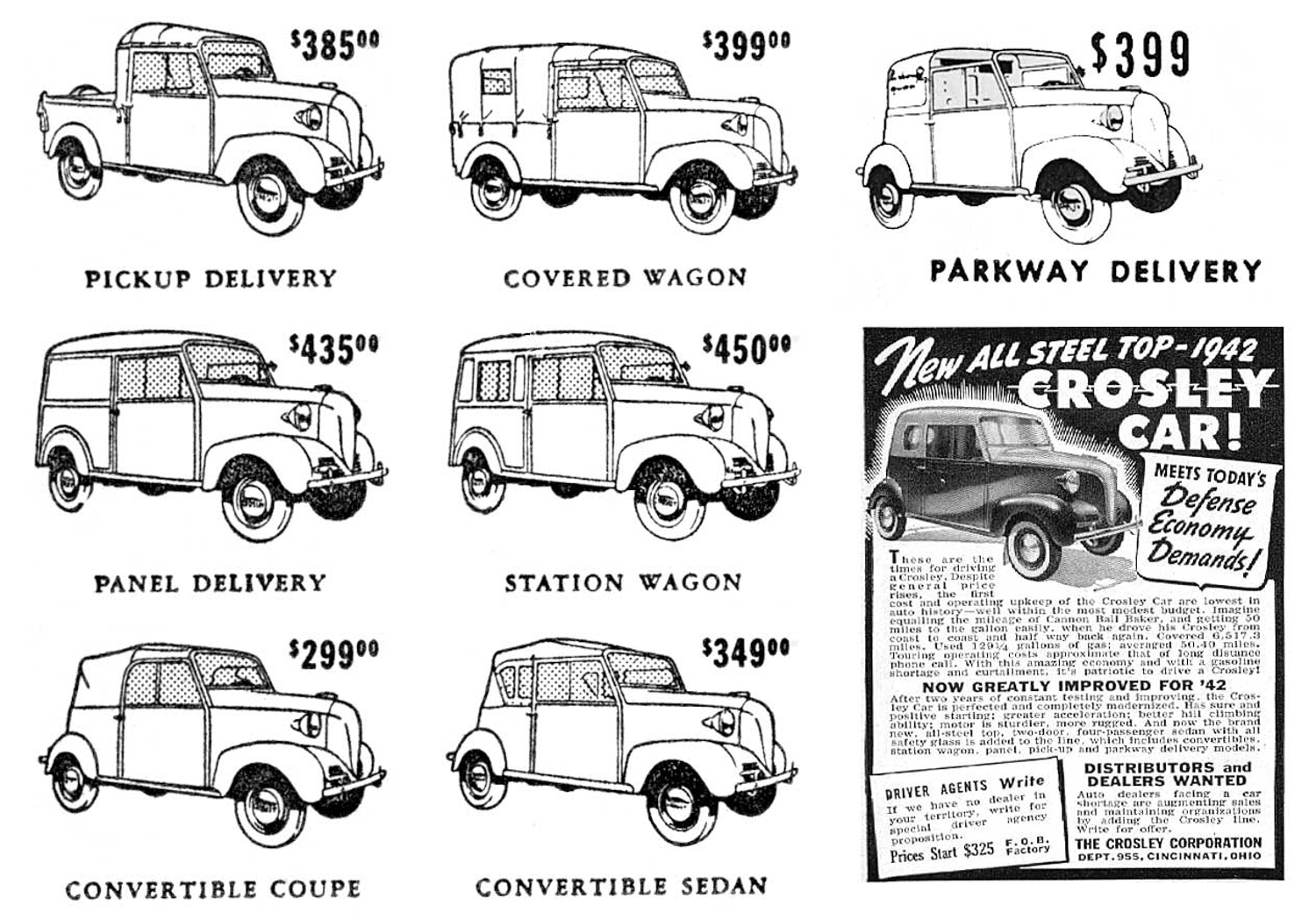

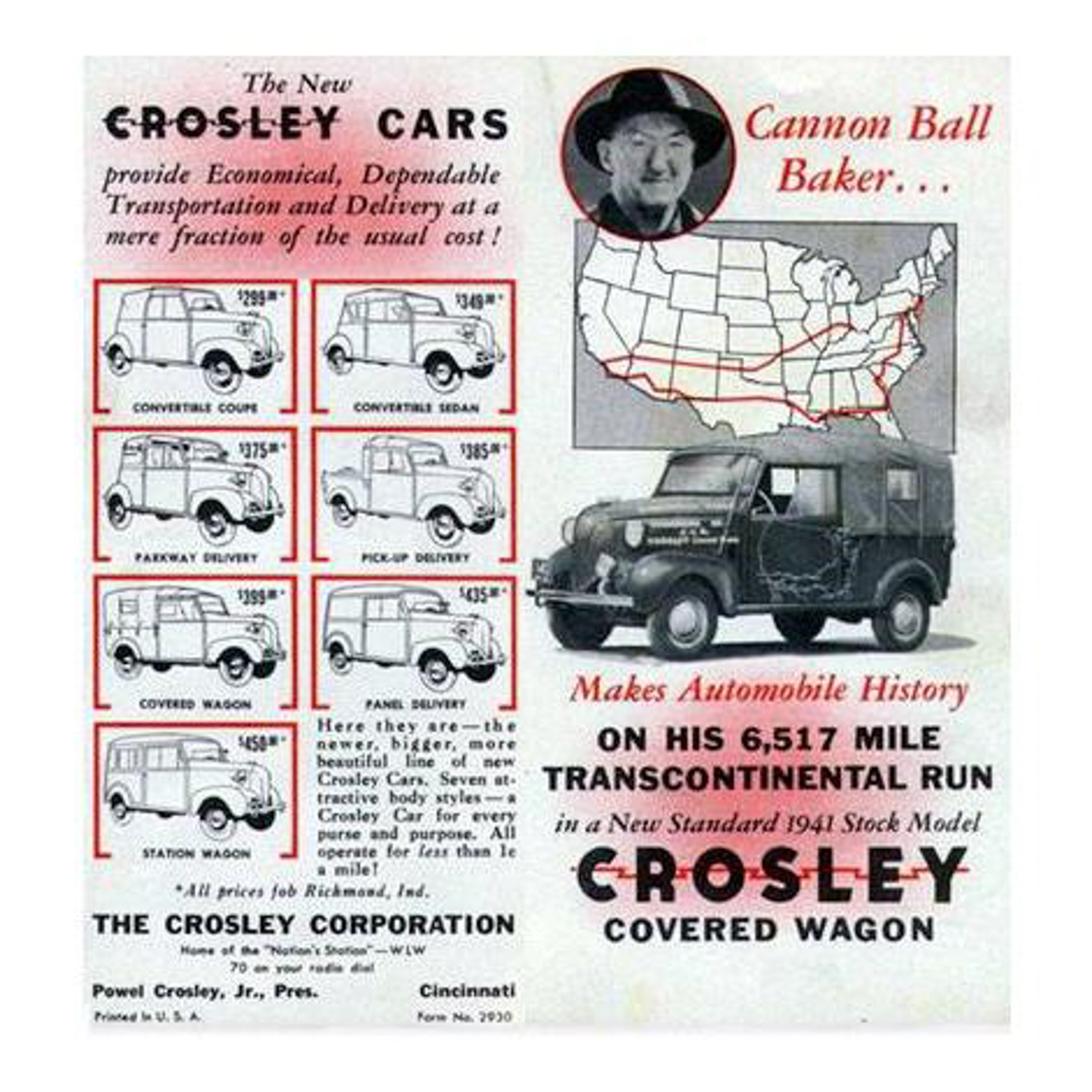

Patents were filed for the cars in July 1938, but there were some changes that needed to be made. The most significant for the company may have been its name change that year. Crosley Radio Corporation became the Crosley Corporation to allow for automobile production. Another name change was for the car, which would now be called a “Crosley.” When Lewis Crosley announced the specifications of the new car on April 2, 1939, it no longer had the narrow rear track. What it did have was an 80” wheelbase and 40” track, a two-cylinder, air-cooled boxer engine displacing 580-cc and producing 13½ horsepower. The Crosley would come as a coupe, sedan, and pickup. It had a three-speed transmission with reverse and an electric starter, but it came with few creature comforts. Standard equipment included a speedometer, oil pressure gauge, and an ammeter gauge. Fuel level was checked with a 24” ruler that doubled as the hood prop. And, of course, a radio was available as an option. The Series 1A vehicles of 1939 all sold for less than $400. The cars were displayed at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, although the first actual showing of a Crosley was on June 19, 1939, in the window of Macy’s Department Store in New York. There was also a chassis displayed inside the store. The display at Macy’s resulted in 14 orders, including two cars ordered by Mrs. Averell Harriman. Powel Crosley wanted his cars to be sold by his appliance dealers, but many were too small to include a showroom and maintenance shop or to take trade-ins. Eventually, Crosley cars would be sold in department stores, by larger Crosley appliance dealers, dealers in other marques, and by newly established Crosley dealers. There was even a dealer in the city of Sitka in the Alaska Territory. A total of 2,017 Crosley automobiles were produced in 1939.

New hires in 1940 worked to improve brakes, drive shafts, and reliability. They also developed a new body design for 1941, added a three-wheeled motorcycle to the Crosley line-up and were in the process of designing a boat. Crosley had plenty of schemes in mind to promote his products, including a drive by Erwin “Cannonball” Baker from Cincinnati to Los Angeles and then to New York. Baker drove 6517.3 miles and got an average of 50.4 mpg. With the prospect of war on the horizon, Crosley Corporation announced 1942 models called the Victory Coupe and Liberty Sedan in the fall of 1941. A possible war allowed Crosley to play up his car’s economy and the resultant support for a possible war effort. It wasn’t long after that the U.S. was in the war, and all automobile production ended in February 1942. Crosley had produced a total of 5,757 cars and trucks by that time.

Wartime production was good for Crosley Corporation. They had ideas for military vehicles, but few were produced. Instead, Crosley had success in selling engines, generators, radios, and proximity fuses. The thought of auto production was never out of Crosley’s mind during the war, and he was ready to get back into civilian production as soon as the war was over. The Crosley brothers were realistic about their ability to compete with the Big Three, but Powel Crosley believed there was room for their small car in the American market. Crosley called it, “The Forgotten Man’s Car.” It was for “the man who didn’t have a fat wallet; who didn’t need a large, shiny car to prove something.” Crosley needed an updated car, and he had Carl Sundberg, a radio designer, work on the body shape and Paul Klotsch direct the engineering design. In order to fund his new automobile, Crosley sold the Crosley Corporation and WLW, providing him with $15 million for his new venture – Crosley Motors – which was incorporated in August 1945 as a public company. Crosley projected production of 150,000 cars per year.

The new Crosley was an entirely new design – longer but narrower than the original, and significantly smaller than the minimally re-designed pre-war cars the Big Three were selling. A major change was the use of the “COBRA” engine. The engine was developed by Lloyd Taylor for an air deployable electric generator. Unlike most automotive engines, the block was not made of cast iron or aluminum, it was made of 125 steel stampings that were crimped or press-fitted together. Copper was melted into the joints which were then brazed using hydrogen, thus the name – COpperBRAzed or COBRA. It was a water-cooled engine with cylinder walls made from chrome-molybdenum tubing and using aluminum pistons. It was a “square” engine, with both bore and stroke of 2¼”, giving it a displacement of 44 cubic inches or 721-cc. It had a single overhead camshaft, a 7.8:1 compression ratio, and a single barrel carburetor. It produced 26½ horsepower at 5800 rpm. A complete engine weighed only 133 pounds. As with the engine, the automobile was built with economy in mind. It had sliding windows, simple external door hinges, a single taillight, no trim, and one door lock. Storage space was in the cavity behind the seats. The only options were a radio, ashtray, and heater.

Gas was still rationed in the years immediately after WWII, so Crosley emphasized the cars gas mileage. It was one of the very few new designs in 1946, and it was inexpensive. Crosley was sure enough of his car that the company did very little advertising – mostly small ads in the back of magazines. The future looked good for Crosley. There were 600 dealers and orders for 30,000 cars. But production was slowed by internal issues and by strikes, and only 5,007 cars and pickup trucks were produced in 1946. Because the cars were unique, they received considerable press, although not all of it was positive. Consumer Reports was not kind in their review, emphasizing “substandard comfort and resale value.” By the end of 1946, new 1947 models were in the hands of the dealers. There were now four models – sedan, convertible, station wagon, and pickup truck – and sales were much better than in 1946. Production was 100 per day. Crosley automobiles were also sold in Canada, Europe, South America, and Asia by Crosley Corporation appliance dealers. Export cars were called “Crosmobiles” in order to avoid any confusion with British engine and vehicle manufacturer Crossley.

Crosley had its best year in 1948, selling 31,570 cars and trucks. By far, the best seller was the station wagon, which accounted for all but about 8,000 of the sales. There were some minor changes for the 1948 models, the most noticeable of which was a change from red to white wheels. A new front piece was added mid-year to change the look of the cars, and Crosley increased its advertising, although they still used small ads in the back pages of magazines. The 1949 models had several important changes, some of which were necessitated by competition. The Big Three all had brand new models, so Crosley was no longer unique. Gas rationing had ended, so gas prices were low and fuel economy was no longer a selling point. Crosley now had a different look at the front with a new grille. The sides were more rounded, and the car now had character lines in an attempt to suggest speed. The car looked larger than its predecessors, but it was the same size. There were two significant changes. The first was four-wheel disc brakes – the first use on a production automobile. The second was an engine change. The COBRA engine had problems. It had a low tolerance for heat, and issues with internal plastic lines breaking down allowed electrolysis causing pinholes to develop in the block. Klotsch developed a new cast-iron block with the same specifications as the COBRA. The new block, called CIBA for Cast Iron Block Assembly, was put in production in late 1948, although the remaining stock of COBRA engines continued to be put in the cars for several more months. Crosley offered to replace COBRA engines for $89 plus the cost of labor. The problems with the COBRA and Crosley’s solution for replacing them resulted in damage to the company’s reputation and falling sales. Crosley’s solution was to change company management.

Crosley Hotshot

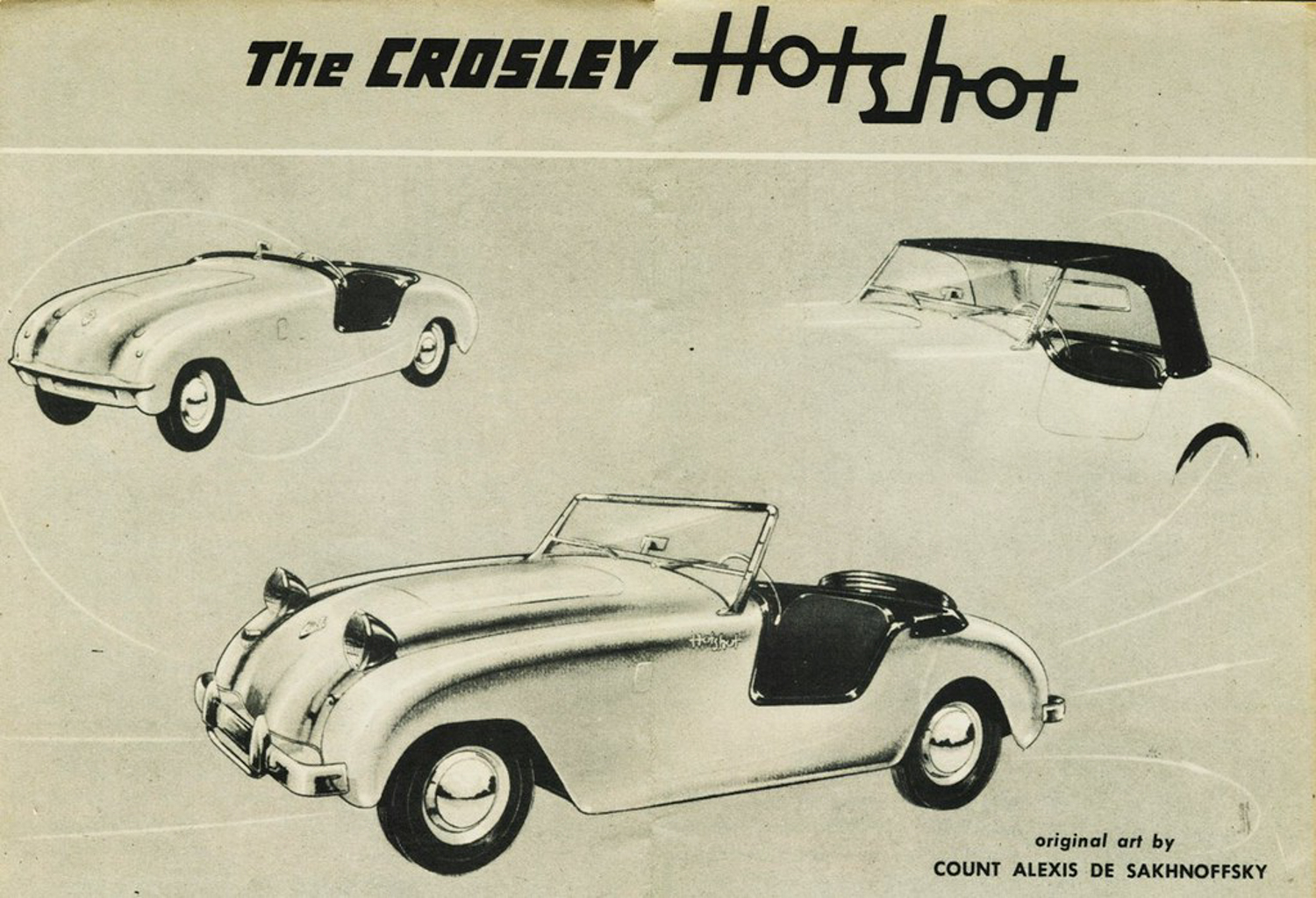

The timing was perfect for a new American two-seater, open car when the Hotshot was introduced in New York on July 13, 1949. American service personnel were coming home from Europe with sports cars like the MG TC, and the only American competition was the Dodge Wayfarer, which was billed as a three-seater and, in comparison to the TC and Hotshot, was huge and cost twice as much. Apparently, Powel Crosley also thought the timing was right, since he projected a demand for 10,000 Hotshots per year. The Hotshot had the 26½ horsepower CIBA engine sitting behind the front axle, making it a mid-engine car. It had a cradle frame, hydraulic shock absorbers, and disc brakes. Its wheelbase was 85”, and it weighed about 1,000 pounds. Rear wheels were driven through a three-speed plus reverse, non-synchronized transmission with the long shifter coming out from under the dashboard, making it possible to hit one’s hand on the ignition key while shifting if not careful.

The Hotshot was designed to be sporty and economical. It had little in common with the other Crosley models except for the engine. It had the typical Crosley high nose, but it dropped at a steeper angle than the other models. It had no grille, and the headlights were mounted in pods high up on the nose. It was pretty basic, with simple seats that Crosley called “airplane type,” a fabric top and side curtains, and optional small doors that could be removed by lifting them off their hinges. As with other Crosley cars, a radio, heater, and ashtray were offered at additional cost. The Hotshot had a spare tire mount, but the tire itself was an extra cost option. The target price was $849, but it actually cost between $935 and $995, allowing Crosley to still claim a price less than $1000.

Powel Crosley claimed that the Hotshot was influenced by classic European racecars, and the car was designed to be easily stripped for racing, a weight savings of 104 pounds. The engine was also quite modifiable. Autocar magazine popped the compression ratio up to 9:1 and used 100 octane fuel to produce 36 hp and a top speed of 84 mph. But the compression ratio of the CIBA engine was easily raised as high as 14:1, giving it considerable potential for development of well more than its stock 26½ hp. In “Crosley and Crosley Motors,” Banks suggests that the Hotshot’s design may have been influenced by another car Powel Crosley owned – a Jaguar XK-120 – and there are some similarities, but it does require some squinting. But it is unknown who actually did the design of the Hotshot. Lewis Crosley influenced a few of the details in order to get the car into production quickly, and it’s possible that there were professional designers involved in the Hotshot design. Tom Tjaarda did a little work for Crosley, but it is more likely that Count Alexis de Sakhnoffsky was the most influential. He had done sketches of Crosley cars for advertisements, and, uncharacteristically, Powel Crosley credited Sakhnoffsky as having contributed – Crosley seldom recognized other people’s contributions.

Production numbers for 1949 were down nearly half from 1948. A total of 7,718 cars had been produced, 752 of which were Hotshots, albeit in a limited run. Sales were slow for all manufacturers, and the big companies were cutting prices, something Crosley was unable to do. It was not a good time to be producing a car as different as a Crosley.

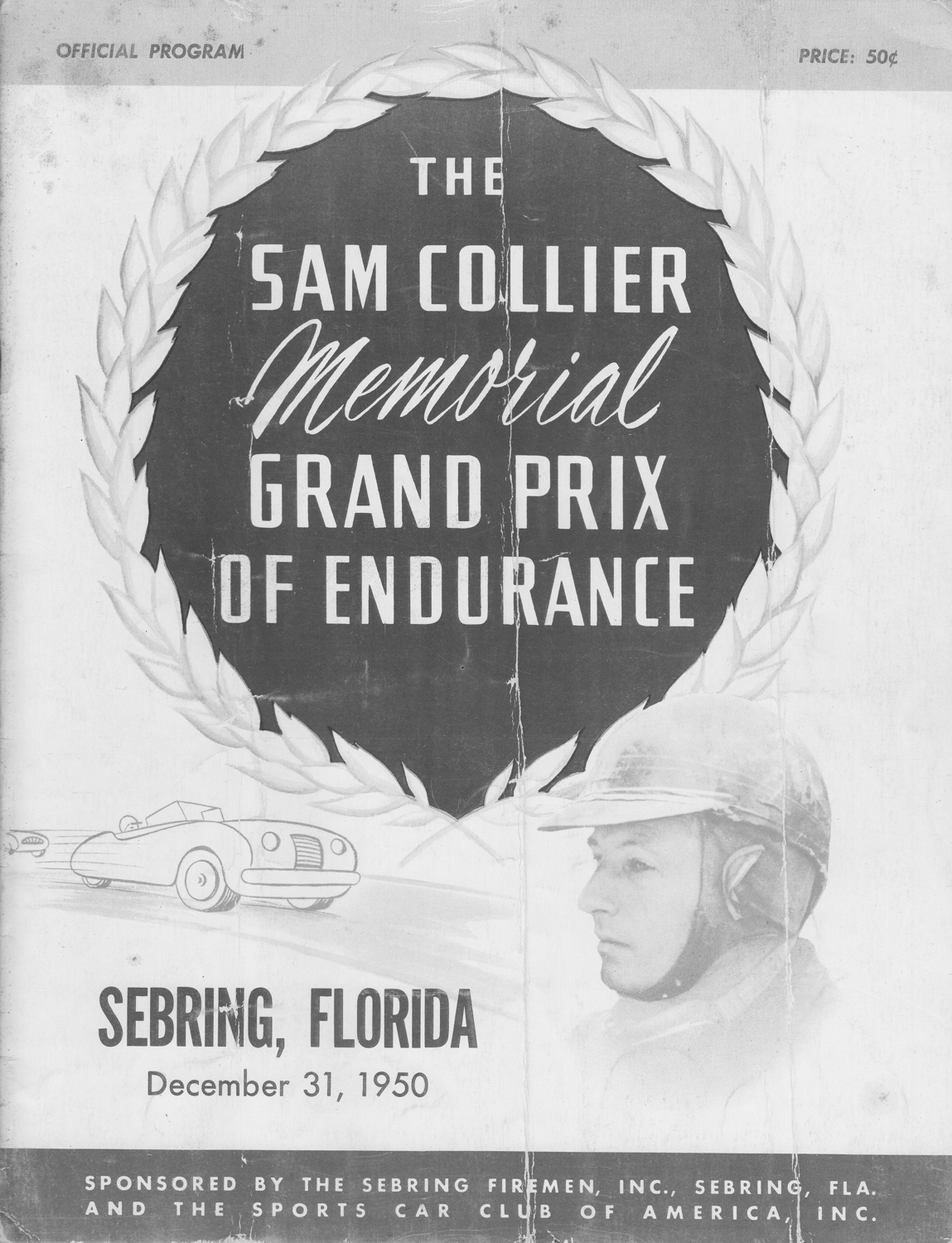

The Sam Collier Memorial Grand Prix of Endurance

On New Year’s Eve 1950, one of the 752 Hotshots that had been produced in 1949 was about to accomplish something few thought possible. A motorsports enthusiast named Alec Ulmann thought it would make good use of the former Hendricks Army Airfield, just outside Sebring, Florida, to have a sports car race. It would be a six-hour endurance race on a course laid out on the airfields runways and taxiways, and it would be called The Sam Collier Memorial Grand Prix of Endurance, a six hour race that would start at 3:00 pm and end in the dark at 9:00 pm. The idea of a winter race in central Florida proved to be popular, and entries for the race included many of the important race teams of the day, including drivers/entrants like Briggs Cunningham, John Fitch, Phil Walters, Alfred Momo, and Luigi Chinetti. They’d be driving Ferraris, Aston Martins, Jaguars, and Allards, to mention some of the faster cars. The story of how a Crosley Hotshot came to be in the race is one of serendipity.

Victor V. Sharpe, Jr., arrived at Sebring to deliver a couple tires to T.L.H “Tommy” Cole for his Cadillac-Allard and to help on his race crew. Sharpe’s family owned a Cadillac, Crosley, and Austin dealership in Tampa, so it was no surprise that his transportation was a Hotshot, with the tires piled in the passenger seat. When Cole saw the Crosley, he thought it might be competitive in the race because of an odd decision made by Ulmann. Normally, the car leading the race at the end of the six hours would be declared the overall winner. But Ulmann liked the idea of a race where the overall winner would be decided on an Index of Performance, although a trophy would also be given to the car that went the farthest distance in the six hours. An Index of Performance had be used for many years at Le Mans, but it was always secondary to the main prize. The formula for the index takes into account the engine size of each entry to produce a target number of laps and average speed for each car entered. Some reports said that a slide rule was found, and the index calculation run. Slide rule or not, the calculation produced a target of 288.5 miles at an average speed of 48.1 mph for the Hotshot over the six hours. Tom Cole would have to go 400 miles at an average speed of 67 mph in his Cad-Allard. If multiple teams met or beat their index, the team that exceeded its index by the largest percentage would be the overall winner. Cole borrowed the Hotshot and ran it on the course to see if it could handle the track. He found that it was sound enough to handle the bumps of the Sebring track and recommended that Sharpe enter the car in the race.

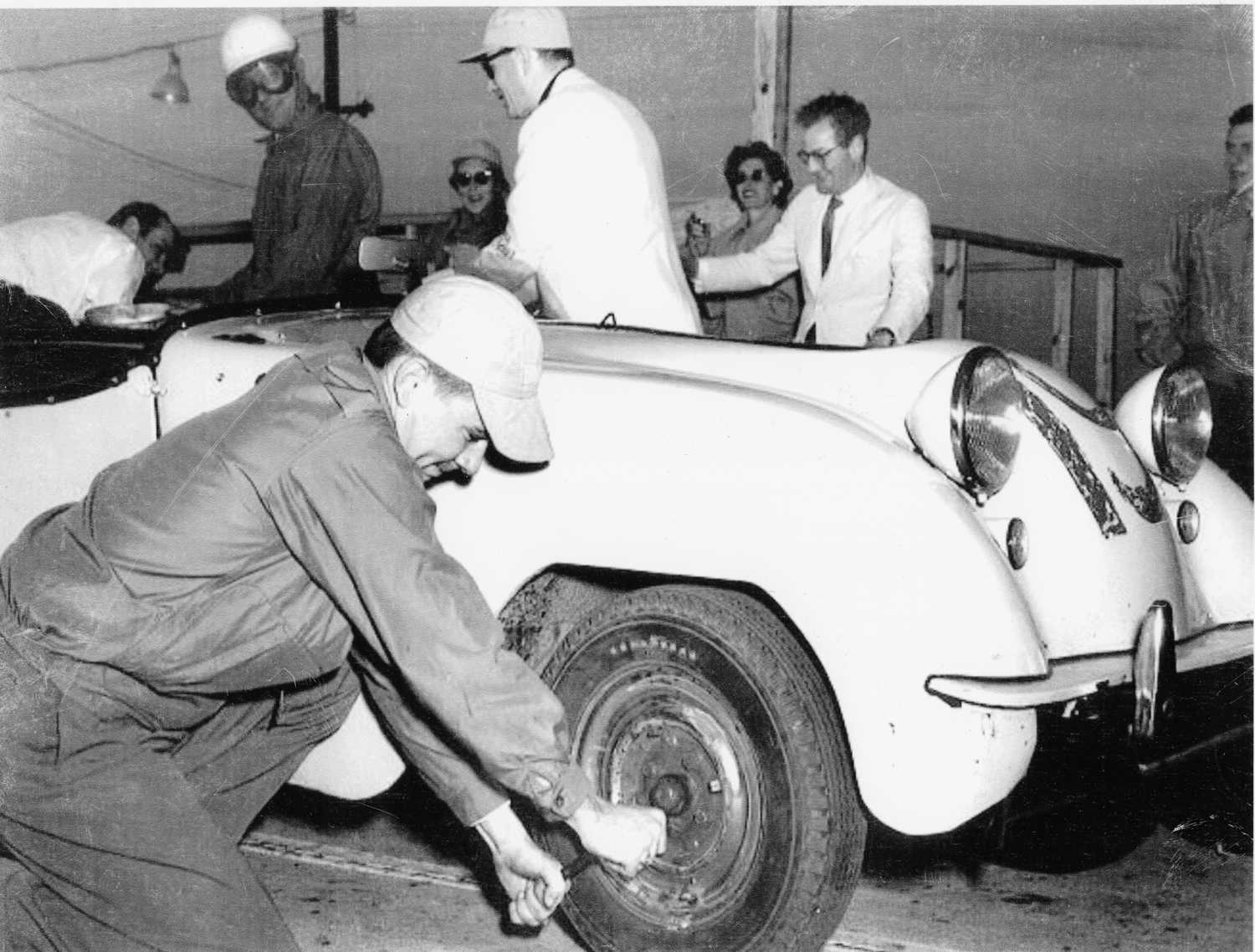

The next challenge was finding drivers for the Hotshot. Sharpe had no race license, and Cole was committed to run the Allard, so they searched the crowd to find a couple of guys Cole knew who had a competition license. Cole had raced with Ralph “Bobby” Deshon and knew he was a decent driver. Deshon had introduced Cole to Fred “Frits” Koster, a Dutch born racer. Both were at Sebring as spectators. Cole introduced them to Sharpe, and the decision was made to enter the Hotshot in the race. Sharpe was not a great fan of the Crosley, having bought it wholesale, so he had little concern about whether it would survive the race or not. The Crosley was officially entered in the race on December 29th, the day before the race. Race preparation of the car consisted of taking off the windshield, bumpers, and hubcaps. A piece of plexiglass was found and crafted into a windscreen, and the car was ready to race. The team visited a store in Sebring and bought a can of black paint and a paint brush. At the track, each team member painted the car’s number, “19,” on one of the fenders and the hood. Each of the numbers were slightly different – unique.

One advantage the Crosley had, other than appearing to have an upper hand with its index, was four wheel disc brakes. A serious disadvantage was its three-speed, unsynchronized gearbox. When anyone described the car’s transmission, they held out two cupped hands, indicating how small it was. As with much of the car, it was designed to be inexpensive not tough. The team realized that there was little chance that the transmission would survive being shifted up and down through the gears for six hours at race speed… even at the Crosley’s race speed. The decision was to avoid shifting except when leaving at the start and from their one pit stop. Their tactic was to keep the accelerator flat to the floor whenever on the straights and use only the brakes and a novel aero device to slow the car for the corners. That novel aero device was the driver. On the straights, the driver would remain hunched down in the cockpit in an attempt to be out of the airstream. Going into corners, he would sit upright so that his head and chest would be in the airstream and help slow the car.

The team made only one pit stop during the race, changing drivers, adding fuel, and checking the lugnuts. The Crosley is reported to have led the index of performance for much of the race. There was a moment, late in the race, when a Ferrari appeared to be catching them, or, more accurately, catching their status of having the best performance according to the index. The team grabbed a black suitcase and showed their driver a message in chalk to “speed up.” He did and at the end they had done 89 laps and had an index score of 1.0854, meaning that they had beaten their index by 8.54%. The second place car was the Ferrari 166 of Jim Kimberley and Marshall Lewis with an index score of 1.0385. Only the top five finishers met or exceeded their index, including a Fiat 100MM, another Ferrari 166, and an MG TC, in that order.

There were a lot of upset competitors when the Hotshot got the big trophy. John Fitch, who had driven a Jaguar XK120, was pretty outspoken, “The index was something off in the distance somewhere. That didn’t matter to us. You raced to win and to get across the line first. The rest was a lot of nonsense.” About the Crosley drivers, he was complimentary, saying that while he was doing 120 mph, they “were puddling along at 70 or so. They didn’t hold up the faster cars. They made it so it wasn’t a problem.” Apparently, there were times when the Crosley hit 80 mph but, compared to the competition, they certainly were “puddling along.” Their average speed over the six hours and 312 miles was 52 mph with a best lap speed of 54 mph, and they got 35 mpg for the race. While an Index of Performance, or Thermal Efficiency, is still popular at some endurance races, it appears that it has never again been used to determine the overall winner.

Bill Cunningham and the Sebring Hotshot

Bill Cunningham could be called a life-long Crosley enthusiast, although he had a detour along the way to Mustangs and still owns a GT 350. He remembers his Great Grandfather having a 1948 Crosley Station Wagon and vaguely remembers riding in it. His Great Grandfather was a big man, so he remembers that there was little room for him in the passenger seat. He had not thought about Crosley cars for quite a while when he saw a Crosley pickup at a car show. It re-ignited his interest, and he started looking for one of his own. In the early ’80s, it wasn’t easy to find a Crosley. You had to search for one. Eventually, he found a project car, then he found a Hotshot. He cleaned that one up and drove it. It got serious, in 1991, when he started going to the Crosley national show. Then Crosleys started finding him! He bought junkers for parts. He bought a number of them at a time. Then he found 14 Crosley’s in Texas – all complete but not great. He did a deal with the former owner, paid for fuel, and the former owner put them all on a flatbed and drove them to Cunningham in Memphis.

By this time, Cunningham was well known in the Crosley world. He was an active member in the Crosley club, and he had become friends with Tim Freshley, a Crosley expert and very competent restorer. It was Freshley who eventually sold the Sebring Hotshot to Cunningham. After the car’s hero status wore off, it remained with the Sharpe family, but it suffered from a lack of attention. Before it deteriorated, though, it was at a show in Texas in 1968, where a young man named Barry Seel saw it and offered to buy it. The owner didn’t want to sell it, so Seel gave him a business card, which the owner put in the glovebox. Years later, after the owner’s death, his daughter found the card. There was a note written on the back saying, “Nice kid. Wants to buy Crosley.” The daughter called Seel, and the car changed hands. Seel was, by then, a Crosley engine expert and competent restorer. He restored the chassis, engine, and all the mechanicals. In preparation of doing the bodywork, Seel had someone start to sandblast the body, but he stopped them because they were starting to warp the sheet metal. Apparently, that was too much for Seel, and he reluctantly sold the Hotshot to Tim Freshley. Knowing the race history of the car, Freshley set out to restore it to its as raced condition. He finished the restoration then undertook having the numbers added to the car. Using original photographs, he projected each number onto the car. His sister, an artist, then hand painted the numbers and made them very close to how they looked on December 31, 1950. The car is restored sans windshield, bumpers, and hubcaps and with a plexiglass windscreen, just as it was raced.

Cunningham was very interested in purchasing the car from Freshley, and, in 2009, Freshley offered the car to Cunningham. Freshley gave Cunningham a year to sell off some of his Crosley cars in order to pay for the Hotshot, and it became Cunningham’s car in 2010. The car changed hands at the Keeneland Concours in Kentucky, where the Hotshot had just won a trophy. While waiting at his trailer to load the car, Cunningham reports that he got a call from Freshley saying, with a laugh, “I’m sitting in line for the winner’s trophy; you better get up here right away. By the way, the price just doubled.” Cunningham became the new owner of the Sebring Hotshot, saying, of Freshley, “He, very graciously, allowed me to be the caretaker of this car.” As the car’s caretaker, he has it on loan to the Edge Motor Museum, a small but high quality museum in Memphis displaying a number of rare American automobiles. It’s a museum worth your time if you’re in Memphis.

Cunningham shows the Hotshot whenever he can, happily telling the little car’s story to anyone who is interested. He’s also trying to get the car recognized as a winner at Sebring. Until the track changed hands some years ago, there was a sign showing all the winners of the races at Sebring. The Crosley was shown in the upper left spot as the 1950 winner of that year’s race. Subsequent owners decided to change that sign to show only the winners of the 12-hour race, so the Crosley is no longer on the sign. Cunningham is working to get some recognition for the car inside the track’s hotel. Hopefully, he’ll be successful.

The End of the Forgotten Man’s Car

Crosley tried to continue production of his automobiles into the early 1950s. He even used a photo of the Hotshot in the winner’s circle at Sebring, although the photo was doctored – mustaches and hats were added apparently so that Crosley would not have to pay royalties to anyone who might be recognized in the photo. New models were added. The cars were updated, with some models getting rollup windows. There were improvements in the clutch, seats, and interior. CIBA engines were popular power plants for sports racing cars and racing boats. Even so, by 1952, Crosley was losing around $500 per car. Powel Crosley was ready to retire, so, with sales falling and mounting losses, he closed automobile production on July 3, 1952. He was able to sell his company to Goodyear, who were looking for more capacity for government contracts during the Korean Conflict, so Crosley made out quite well. Powel Crosley died in 1961, still a very wealthy man.

Driving Impressions

After hearing Cunningham’s cautions about difficulties with shifting the Hotshot’s transmission and finding the driver’s side of the car very difficult for an old guy to enter, I opted for having him give me a ride in the Crosley. Even with the doors open, the Hotshot is not an easy car to enter. The best way to get in the passenger side is to lift your left leg high over the raised body sill, brace your hands on the seatback and body (not the door), lift up until you’re nearly standing, then swing your right leg into the car and slide down into the seat. Cunningham has a lot of experience driving Crosley cars, and the effort it took to shift the Hotshot made me glad of my decision not to try it.

It has a delicate transmission, and I didn’t want to be the guy who broke it. The car is underpowered, but it is also very light, so it is surprisingly quick. The power to weight ratio is good. Cunningham took me on a ride on city streets near the museum, but he chose a route with plenty of corners, and the Hotshot took them very well at speed. There was some lean in fast corners, but my Alfa Romeo sedan leans more than the Hotshot. I can’t say the seats provide a lot of lateral support, so holding onto the doorframe was necessary. I have to admire Koster and Deshon for being able to drive the car at speed for three hours each, but I bet they had a smile on their faces while they did it. I certainly was smiling during my ride.

Specifications

| Chassis | Cradle frame |

| Length | 137 inches/3480 mm |

| Width | 51 inches/1295 mm |

| Height | 51 inches/1295 mm |

| Wheelbase | 85 inches/2159 mm |

| Front and Rear Track | 40 inches/1016 mm |

| Weight | 1175 lbs/533 Kg |

| Body Style | Roadster |

| Drag Coefficient | 0.5 (estimated) |

| Engine | Front, mid-engined CIBA – Cast Iron Block Assembly 4-cylinder, single overhead camshaft. |

| Drive | Rear-wheel drive |

| Displacement | 44.2 cid/724 cc |

| Bore/Stroke | 2.5 inches (63.5 mm)/2.25 inches (57.15 mm) |

| Power | 26.5 hp/19.8 KW @ 5400 rpm |

| Torque | 33 ft-lb/45 Nm @ 3000 rpm |

| Compression Ratio | 9.8:1 |

| Carburetion | Single Tillotson DY-9C single barrel carburetor |

| Transmission | 3-speed non-synchromesh with reverse |

| Drive | Rear-wheel drive |

| Brakes | Goodyear-Hawley Aircraft style 4-wheel disc |

| Shock Absorbers | Hydraulic |

| Tires | 4.50/12 |