1955 Austin-Healey 100S

It was as black as the inside of a coalmine as we left the comfort of the Cadillac back at the roadside. My friend, Alan, and I had been staying with friends in Oregon in 1975 when, over a very passable glass of Californian red, the subject of the Austin-Healey 100S came up. Our friend mentioned that he had heard from a local that the remains of a 100S was under a lean-to just 60 miles away. A phone call later—and the red soon forgotten—we were on our way.

Reading from some scribbled instructions, we stopped at what looked to be the middle of way out past the black stump (useful Australian expression meaning the middle of nowhere). It was certainly black outside but armed with a flashlight we marched off into the gloom to be confronted by long grass, briar and bramble. Some 20 minutes later we found what looked like an old storage shed and, sure enough, lying under some sheets of iron and the odd vine or two, was an Austin-Healey chassis. Well, I suppose it would be more correct to say what was left of an Austin-Healey chassis, as it had been severely cut away from the firewall and footwells forward.

A quick check confirmed that it indeed was a 100S chassis but as with so many old competition cars, a previous owner, through the ever-increasing search for more power, had hacked the chassis up, installing a V-8 before it was left to rot in the field.

Now, some 29 years later, that very same Austin-Healey 100S that Alan and I found was just a car’s length behind me while I, too, was driving a 100S and in front of me was yet another one. I suppose this sounds as if the 100S was quite common but with just 55 built it has become the most desired of all Austin-Healeys built and these days has become a very big-ticket item indeed.

Built for Racing

Donald Healey was no stranger to the world of motorsport, with a successful European rally history behind him. With the introduction of cars under his own name following WWII he set out to promote the new Healey marque through competition.

The first Healeys were more bespoke vehicles with alloy bodies over timber frames. Powered by a 2.4-liter Riley engine, the first Healey to appear on the international motorsport stage was a saloon that won its class in the 1947 Alpine Rally. Other rallies and road races followed, including the father-and-son team of Donald and Geoffrey Healey finishing 2nd in the unlimited sports class in the 1948 Mille Miglia.

The Spa 24 Hour race of 1948 was to be the debut circuit race for the new Healey, with a saloon finishing 2nd in the 2-3 liter class.

While the original Healeys were, and still are, wonderful touring cars, they were not quite suitable for the weekend racer. In 1949, Donald Healey satisfied the demand with the release of the new Healey Silverstone and started a tradition of producing specialist sporting cars suitable for use on road and track. While the Healey saloons and roadsters were well fitted out vehicles, the Silverstone carried the bare necessities with a cigar-shape alloy body over a steel hoop frame.

The Silverstone ran with considerable success in rallies and on circuits all over Britain and Europe. Briggs Cunningham was an early customer running a Cadillac-engined version in the January 1950 Palm Beach Road Races and the Watkins Glen Sports Car Grand Prix of the same year.

A chance meeting in 1949 with George Mason, president of Nash Kelvinator, gave birth to the Nash-Healey. With engines, gearboxes and other components sent across from the U.S., the initial cars were built in England with later cars fitted with bodywork by Pininfarina in Italy.

With the Nash straight-six fitted with a new aluminium cylinder head, sports camshaft and twin SU carburetors the new car made its competition debut in the Mille Miglia in 1950. However, it was at Le Mans where the car shone with a 4th place in the same year. The following year they were up against the likes of Jaguar, Talbot and Cunningham and managed a 6th place overall. However, the best was yet to come in 1952 with a 3rd place behind Mercedes in 1st and 2nd, ahead of teams from Ferrari, Jaguar, Cunningham and Aston Martin.

Austin-Healey Debut

How the 2.6-liter, four-cylinder Austin-powered Healey 100 became the Austin-Healey 100 at the 1952 London Motor Show is well known. The subsequent contract with the British Motor Corporation meant the Donald Healey Motor Company (DHMC) would produce the racing versions.

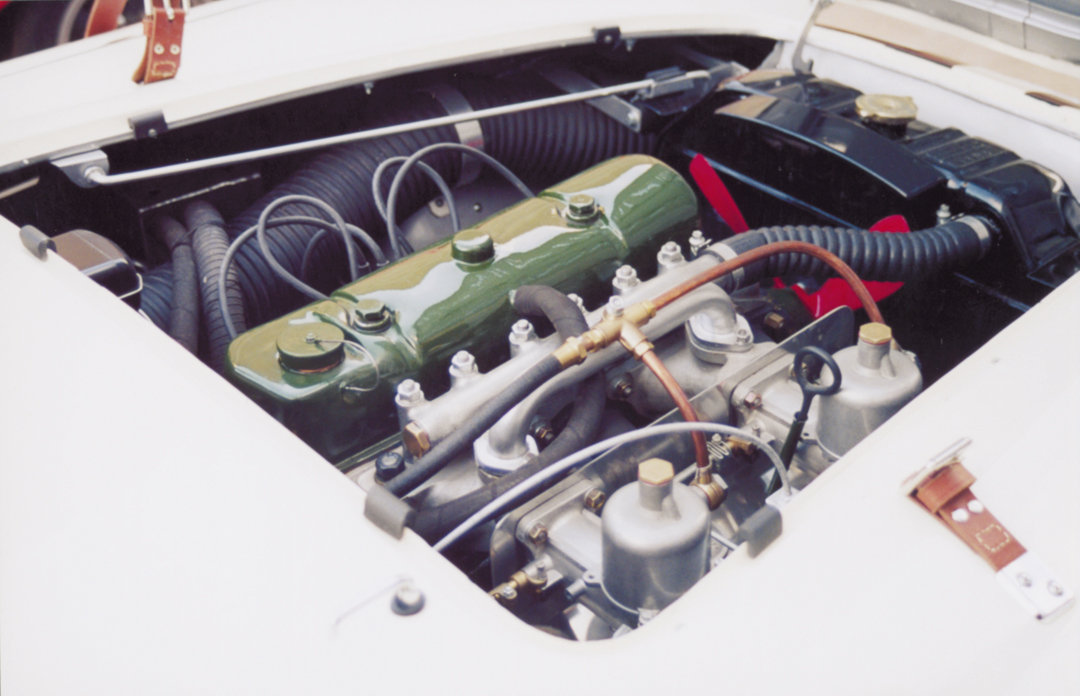

Photo: Patrick Quinn

Le Mans 1953 was the event and two cars were entered. Externally, the Austin-Healeys looked standard but significant mechanical modifications had been carried out. Fitted with a higher axle ratio, the cars were timed with a top-speed of just less than 120 mph. After 24 hours, one Austin-Healey finished in 12th position, having covered 2,153 miles at an average speed of just less than 90 mph.

While success at Le Mans was highly important to the small Warwickshire company, it was the crucial U.S. market where the greatest sales potential lay. To publicize the new Austin-Healey, Donald Healey prepared for record-breaking at Bonneville, Utah for the close of the 1953 competition season. One car was prepared at Warwick while the other, a standard car, was selected by officials of the American Automobile Association from an American Austin dealer.

With Donald Healey leading a team of drivers including George Eyston, John Benet, Roy Jackson-Moore and actor Jackie Cooper the two cars captured more than 100 records. The standard car averaging 104 mph for 24 hours gained all U.S. records for its class and the tuned car achieved a timed speed of 142.6 mph.

Sebring Success

Again, with the immense U.S. market in mind, a single car was prepared for the 1954 Sebring 12 Hours. It too looked like any other Austin-Healey 100, but the original cast-iron cylinder head was replaced by a Weslake design with improved breathing from separate inlet and outlet ports on the reverse side from the pushrods.

Other modifications included a more robust David Brown gearbox, Dunlop center-lock disc wheels and, importantly, Dunlop disc brakes on all four wheels.

Photo: Patrick Quinn

Before the race the big interest was on the works teams from Lancia, Cunningham, Ferrari, Aston Martin and Maserati. Lancia brought along drivers of such caliber as Fangio, Ascari and Taruffi. While none were entered by the factory, there were also a total of 11 Jaguars in the field, as well.

From the start Taruffi was in front, driving his Lancia D-24, with Ascari and Fangio close behind with the Ferrari 375 of Bill Spear and Phil Hill in 4th. Two hours into the race, the lone Austin-Healey driven by Lance Macklin and George Huntoon was in 7th place and running very reliably. By halfway Fangio and Ascari were out with engine trouble and Phil Walters and John Fitch were 2nd in the Briggs Cunningham–entered Ferrari 375. Two hours later all the Ferraris had dropped out, as had the Cunninghams. The Austin-Healey was now in 2nd place with the Cunningham- entered OSCA MT4 of Stirling Moss and Bill Lloyd behind.

Towards the end of the tenth hour, Taruffi was slowing with engine difficulties and Macklin pushed the Austin-Healey in the hope of taking the lead. Without warning the Austin-Healey went off song but stayed in 2nd place until passed by the OSCA that was quickly running out of brakes. With just 53 minutes to go, Taruffi pushed his Lancia into the pits with a seized engine but was subsequently disqualified, as it had previously left the pits without the use of its own starter.

Photo: Autofan Media

The Austin-Healey’s loss of power was caused by a broken rocker arm but it stayed in the race, only to be passed by the Lancia D-24 of Rubirosa and Valenzano. The race finished with the OSCA 1st, Lancia, 2nd and the Austin-Healey, 3rd.

The 3rd placing came as a complete surprise to the small team from the DHMC, who were, of course, ecstatic with the result.

The 100S

Donald Healey was quick to capitalize on the Sebring success and saw a small gap in the market for a well-priced competition car, not unlike that of the earlier Healey Silverstone. At the 1954 London Motor Show, the Austin-Healey 100S was announced. With the “S” standing for Sebring, in commemoration of the success of earlier that year, the 100S has gone on to be one of the most well-sought-after of all Austin-Healeys.

Externally and internally, the 100S was very different from the standard Austin-Healey 100. With all-alloy bodywork and subframes, full-width Perspex racing screen, rudimentary upholstery and 20–imperial gallon fuel tank, the 100S weighed in 220 lbs lighter than the standard 100. While the 100 engine produced 90 bhp, the 100S engine with alloy cylinder head and revised camshaft profile punched out 132 bhp from its 2,660 cc. Fitted standard with a low 2.92:1 ratio differential, the car was good for 0–60 in 9.8 seconds, standing quarter mile in 16.8 seconds with a top speed of 125 mph. Stopping came from four-wheel Dunlop disc brakes. To the end of Austin-Healey production the 100S retained the title of being the fastest model produced.

Production facilities at the Donald Healey Motor Company were tiny, necessitating that the 100S be built in batches of 10. In total, just 55 examples, all in right-hand drive configuration, were built during ’54 and ’55, nearly all in the color scheme of Lobelia Blue over white.

Photo: Ozzie Lyons – www.petelyons.com

One of the first competition events for the new model was the 1954 Pan-American Road Race. Two cars were entered with Lance Macklin and Carroll Shelby as drivers and Roy Jackson-Moore and Donald Healey as reserves. However, the race was not to prove a success, as Macklin was disqualified after being late in a stage and Shelby crashed heavily, breaking his arm.

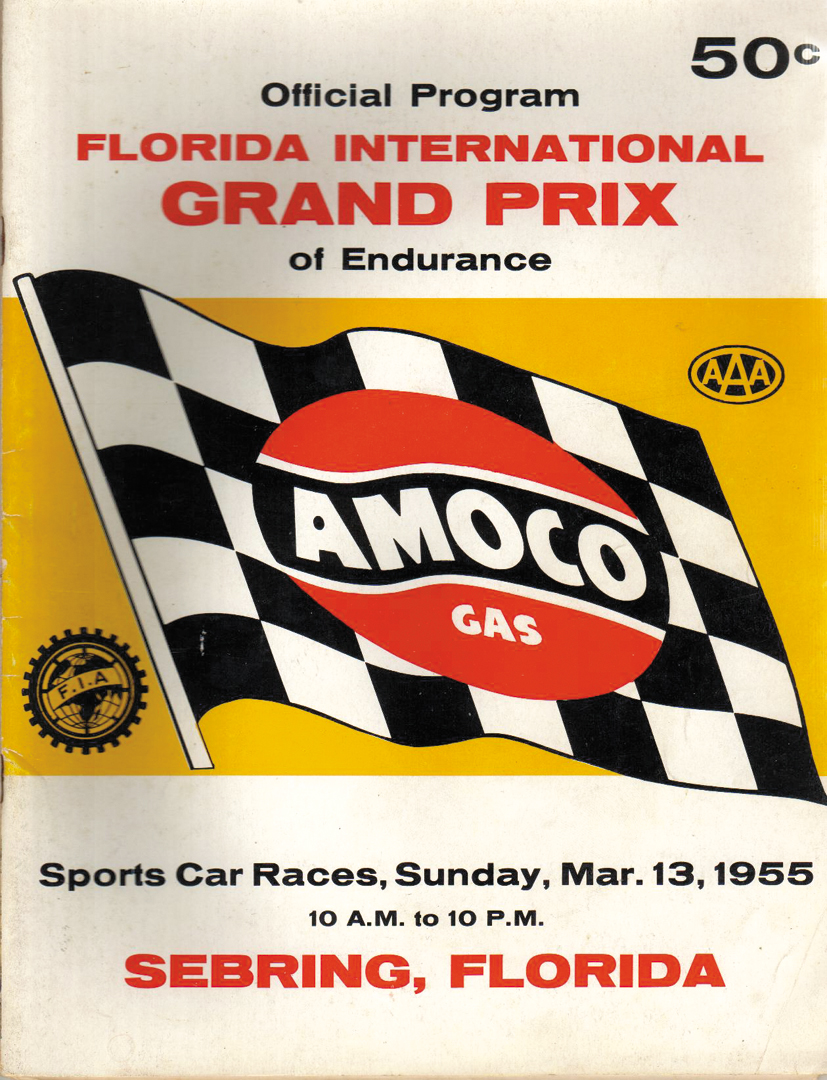

Return to Sebring

For Sebring in 1955 the DHMC prepared two 100Ss, with Stirling Moss and Lance Macklin driving one car and Jackie Cooper and Roy Jackson-Moore, the other. By early 1955 the 100S was well and truly available on the U.S. market and there were a further six examples driven by the teams of William Brewster/Charles Rutan, Bill Cook/George Rand, Joseph Guibardo/Fred Wolf, Bill Wonder/William Wellenberg, Bob Wilder/Rowland Keith and Gus Ehrman/Fred Allen.

Once again the money was on the big-name entries like Ferrari, Maserati and Jaguar but Moss, after his usual super quick Le Mans–style start, was soon up in 9th place with Jackie Cooper not far behind. Two thirds through the race, Moss and Macklin had climbed to 6th behind two Ferraris, a couple of Maseratis and a D-type. Back in 15th was the car of Brewster/Rutan and just behind them were Cook and Rand. Unfortunately, Jackie Cooper had earlier enjoyed the delights of a sandbank and was out of contention.

Moss and Macklin maintained their position through to the end of the twelfth hour and managed a 1st in the Series Production Class with Brewster/Rutan, 2nd and Cook/Rand, 3rd in the class. The winner was the Briggs Cunningham–entered D-type Jaguar of Mike Hawthorn and Phil Walters.

Unfortunately, the success of the previous years was to elude them in 1956. The DHMC entered two 100Ss for the event, with each car breathing through double Webers and producing 145 bhp—both cars looked destined for success. However, the cars driven by Macklin/Archie Scott-Brown and Jackson-Moore/Elliott Forbes-Robinson both dropped out with broken exhaust systems. William Brewster and Bill Rutan backed up for the second year in their 100S but were out after 39 laps with gearbox problems. The most successful 100S was driven by Phil Stiles and George Huntoon, finishing in 11th place after covering 168 laps, some 26 laps behind the winning Ferrari 860 Monza of Fangio and Eugenio Castellotti.

It is worth mentioning the unfortunate role played by the 100S in motor racing’s most infamous disaster. Lance Macklin was driving a works-entered car at Le Mans in 1955 and, while running down the straight, took evasive action against Mike Hawthorn’s D-type Jaguar. However, coming up behind was the Mercedes of Pierre Levegh which, on hitting the rear of the 100S, launched itself into the crowd, killing more than 80 spectators, as well as Levegh.

100S Restorer

I had driven a few Austin-Healey 100Ss over the years but nowhere near the number of my fellow Australian and friend Steve Pike, who now says with some enthusiasm that his tally has reached 28—not bad out of a total production of just 55. However, I have never had the excitement of driving one as part of a group. We were northwest of Melbourne, the capital of the Australian state of Victoria in what is called the Rowsley Valley where trees are scarce but granite outcrops abound. The countryside is starkly beautiful with rolling hills, and the roads are a combination of long sweeping curves intersected by the occasional straight. One of the interesting things about the 100S is that everyone talks in chassis numbers. There is not that many of them and I suppose that’s one way of keeping track.

I had taken up Steve and Helen Pike’s long-standing invitation to view the 100Ss at Steve’s restoration business. Seeing a total of three ready for the road and a further two under restoration is rather mind-boggling when the rarity of the model is taken into consideration. As I said earlier, the car behind our little caravan was the Austin-Healey 100S AHS 3510 that we found under the lean-to back in 1975. The car I was first to drive (AHS 3507) was purchased new by well-known Broadway, New York restaurateur Vincent Sardi and driven by him at various U.S. East Coast races back in the 1950s. However, the provenance of the 100S sporting the number 45 (AHS 3506) is impeccable as it was raced by William Brewster and Charles Rutan at Sebring in 1955 and 1956. The other two cars under restoration were Australian delivered cars AHS 3906 and AHS 3907.

Sebring, Florida and the countryside of Victoria, Australia are continents apart but Steve has earned himself the reputation as being second to none when it comes to his knowledge and restoration of the 100S.

Steve bought his first Austin-Healey when he was just 20 and, like many owners of the time, aspired to own the coveted 100S. His interest was racing back at that time and he thought that a 100S would be the car to use. However, then as now, the model is elusive and he went to the other extreme by purchasing one of the three Rolls-Royce–powered Austin-Healeys produced.

However, the idea of owning a 100S continued to burn in his brain and the opportunity came when, for the princely sum of just $100 (U.S.), he purchased the remains of the car we found during that black night in Oregon. It wasn’t all that long before it was back to being a rolling chassis but, as happens, other directions took control and it was sold to fund the establishment of his vehicle-restoration business.

Photo: Ozzie Lyons – www.petelyons.com

It also didn’t take long for the word to get around and Steve and Helen’s business became known throughout Australia. Another 100S was purchased in 1983, restored and eventually sold.

The Brewster/Rutan 100S

The history of the ex-Brewster/Rutan 100S after Sebring in 1956 is not entirely clear, but it is known that it saw service at Watkins Glen. Like most competition cars, it soon became just yesterday’s racecar and was sold off to be replaced by something a little more competitive. The current owner is Jon Savage, who lives on the East Coast and, wanting to get into a 100S, made contact with Steve hoping that Steve might be able to help. With his eye very much on the 100S’s around the world, Steve did know of one that might be up for sale in Texas.

After its racing career, the Brewster/Rutan 100S found its way to Tortola in the Virgin Islands, where it sat rotting in a banana plantation. Thankfully, it came up for sale during the mid-1970s, when it was purchased by an enthusiast in Connecticut who had it shipped first to Miami and then north. It was then sold in 1986 to another enthusiast in Texas who had some work carried out on the car’s bodywork before, once again, it sat awaiting its fate.

Following some six months of negotiations, Jon Savage became the new owner of the Brewster/Rutan 100S and, before even seeing his new possession, had it shipped to Steve Pike in Australia for restoration. Steve says it certainly gave him a boost when Jon Savage was happy to send him the car along with his full and absolute trust.

“Despite being unused for years, the body was in excellent condition.” Steve Pike told VRJ. “I think its racing years must have been kind to the car, as it hadn’t seen too many accidents. On arrival in Australia there was just 25,500 miles showing on the clock. I was a little dubious about this at first but I have found the easiest way to check this is to look closely at the wear on the brake disc rotors and door catches. Although rusty, the rotors were in surprisingly good condition and showed the amount of wear you would expect for a car with that sort of mileage. The door catches were also in excellent condition.”

“From what we have found out, the car was probably raced from 1955 through to 1965 and not much since. There is really nothing unusual with that as by the mid-’60s the car would have been just another old sports car; AHS 3507 and 3510 are also typical examples of this. The ex–Vincent Sardi car was raced extensively by Sardi and, despite receiving quite a few modifications such as the extra cooling holes beneath the grill, soon became yesterday’s racecar. Subsequent owners had problems with the aluminium cylinder head and then someone started preparing it for a V-8. Luckily, it was purchased by an American Austin-Healey enthusiast and initially restored in the U.S. He then took it to New Zealand and it then found its way here for a little refreshing before going to a new owner in Switzerland. AHS 3510 was fitted with a V-8 but severely damaged in a road accident before being left to rot away under the lean-to.”

“The 100S was very much a competition car.” Steve added. “Certainly not built for a long racing life and, in fact, rather short term, like most racing cars. It is surprising how many still exist almost half a century later.”

Driving an Austin-Healey 100S

You would think that the very low differential ratio of 2.9:1 would be more of a hindrance to performance than a boost, but far from it. While the standard Austin-Healey 100, with just 90 bhp, is no sluggard, the 100S feels positively alive.

Punting the ex-Sardi car along those delightful rolling roads was a delight. The exhaust of the standard 100 exits at the left rear but with the 100S there are twin pipes exiting just behind the driver’s door, emitting a wonderful cackle. Like most competition cars, there is a certain urgency when driven with any degree of enthusiasm.

The urgency is even more pronounced when behind the wheel of the Brewster/Rutan 100S, as its new owner had a date at the Monterey Historic Races last August and Lime Rock a few weeks later. His instruction to Steve was to prepare the car with racing in mind. So the engine was breathed on just that little bit more and down the back was a 3.6:1 differential.

The difference was amazing. While the Sardi car would power its way smoothly through tight corners, the rear of the Brewster/Rutan 100S squatted in the corners and with a little flick of the steering wheel it was around and bellowing towards the next corner. On the straight, the rev counter spun readily towards the red line while the legal speed limit was left far behind.

Living with a 100S

While built for racing, the 100S is relatively straightforward to look after, not unlike the production Austin-Healey. With a robust chassis and an engine that shares its design with that of the 1950s London taxi, a properly cared-for example will provide years of enjoyment.

The original aluminium cylinder heads did cause problems, but with advances in technology new heads are available and, if fitted correctly, will keep all the fluids correctly in place. In fact, due to the efforts of people like Steve Pike and others throughout the world, those early troublesome components are all now reproduced, albeit in very small numbers. Heads, brake calipers/rotors, manifolds, oil coolers/filters and the numerous brackets, pipes and so on that are peculiar to the 100S are all available.

According to Steve Pike, servicing is virtually no different than with any other Austin-Healey. This means regular oil changes including the filter that is, in the case of the 100S, a large cartridge that fits into a cylindrical oil cooler below the radiator. Greasing the front end, rear spring hangers and drive shafts should also occur when the oil is changed. Plus, as the Armstrong lever type shock absorbers are oil filled, these should be checked as well.

The market for the Austin-Healey 100S is very buoyant at the moment and with 47 examples known to exist out of the original 55, they do come up for sale occasionally. However, cars in good to excellent condition command premium prices with examples recently sold for $235,000 (U.S.) with ex-works cars selling for quite a bit more.

Specifications

Chassis: Box-section steel frame with riveted alloy sub-frames

Body: All-alloy two-seater bodywork

Wheelbase: 7ft 6in

Weight: 1,888 lbs

Front Suspension: Independent with coils, double acting Armstrong shock absorbers and anti-roll bar

Rear Suspension: Semi-elliptic springs, double-acting Armstrong shock absorbers and Panhard rod

Steering Gear: Burman cam and lever

Engine: Four-cylinder, 2,660cc (87.3mm x 111.1mm)

Power: 132 bhp at 4,700 rpm

Carburettor: Twin SU H6

Clutch: Single dry plate

Gearbox: BMC C-series close ratio

Gears: Four forward, one reverse

Foot Brake: Four-wheel Dunlop single-pot discs

Hand Brake: Operating on rear discs

Wheels: Wire-spoke knock-on wheels

Tires: 5.50 X 15 Dunlop racing

Resources

Browning, Peter and Needham, Les. Healeys and Austin-Healeys. 1970. G T Foulis & Co Ltd, ISBN 0-85429-101-6

Healey, Geoffrey. Healey, The Specials. 1980, Gentry Books. ISBN 0-85614-062-7

Breslauer, Ken. Sebring, The Official History of America’s Great Sports Car Race. 1995, David Bull Publishing. ISBN 0-9649722-0-4

Many thanks to Steve and Helen Pike for their hospitality and the opportunity to test these English-built racing thoroughbreds. Also thanks to Jon Savage for his kind agreement to allow VRJ to test his 100S even before he saw it, let alone get behind the wheel.