1972 Eifelland Type 21

The 2016 Formula One season found the World Championship taken by a German team, Mercedes, and a German driver, Nico Rosberg. Germany has had many successes and failures during the history of motor racing and the life of the modern Formula One World Championship. While pre-war the Auto Unions ruled motor racing circuits and post-war the Mercedes Silver Arrows made a significant mark until the tragedy at the 1955 Le Mans 24 Hours, it’s difficult to appreciate that it took until 1994 for Germany to produce an F1 World Championship driver—Michael Schumacher. Although 1970’s posthumous World Champion Jochen Rindt, had been born in Germany, he represented his grandparents’ homeland, Austria. Since then, a German driver has won the championship on 11 more occasions, with Schumacher’s iron grip on the series from 2000-’04 being the highlight—albeit aboard an Italian car, Ferrari—before Sebastian Vettel’s four-year domination from 2010-’13 with Red Bull, an Austrian marque.

So, Rosberg’s World Championship title is a unique achievement from a German perspective. This battle has taken six decades to realize, but there have been many who’ve tried over that time with teams including Porsche, ATS and briefly Eifelland. Our profile this month looks at the story of the German Eifelland Racing Team chasing the dream and trying to attain motor racing’s ultimate accolade. The story includes the tale of a German Caravan company, Eifelland, an eccentric German sculptor/industrial designer and a great German sportscar driver who wanted to win the F1 World Championship.

Eifelland Caravans

The Eifel region of Germany is a low-mountainous area situated in the western part of the country, close to both the Luxembourg and Belgium borders. Part of the district includes the Nürburgring race circuit at Nürburg, and near to the town of Mayen—home of the Hennerici brothers, Gunther and Heinz, both passionate motor racing fans. It was the closeness of the racing circuit that stirred the brother’s fervor for the sport. In 1967, together with other local race fans, they were responsible for the reformation of the Automobile Club 1927 Mayen eV—a single entity born out of the remnants of three former clubs. Heinz Hennerici, despite the loss of his left arm during the Second World War, was a keen racer and was closely associated with the Nürburgring circuit for most of his life. Meanwhile, brother Gunther specialized in the building of trailers/caravans, his business was called Eifelland Wöhnwagenbau.

Photo: John Colley

With the advent of sponsorship in motor racing, Gunther thought he’d use some of the company-advertising budget on motor racing. Over a very short period of time this turned into entering the sport as a full-time racing team in several formulae of racing including Formula Two. Many notable drivers were seen aboard Eifelland-entered cars including Dieter Quester, Hans-Joachim Stuck, Rolf Stommelen and Hannelore Werner, who would go on to became Gunther’s third wife.

Gunther Hennerici had poured a great deal of money into a German rising star driver, Rolf Stommelen, but he thought it a great investment, if only his sportscar form could be translated into Grand Prix racing. He felt that a major problem lay in the fact that he hadn’t got the backing of a German works F1 team behind him. As the 1972 F1 season neared, Gunther thought that, rather than continue sponsoring his driver to race for a rather lackluster John Surtees/Rob Walker/Brooke Bond Oxo-type outfit, he’d plough his DM5,000,000 budget into a project to build his own F1 car. Eifelland money augmented with other sponsorship from the German Auto Motor und Sport magazine and Ford Cologne would surely produce a winning team.

Lutz “Luigi” Colani

Photo: John Colley

Lutz Colani, today known as Luigi Colani, was born in Berlin, Germany, in August 1928 of Polish and Kurdish descent. His father was from Switzerland and worked as a stage designer. Colani believed his own eye for design was directly from his fathers’ genes, noting that he believed Colani Sr. was an incredibly gifted man whose hands and mind were superior to anything he has become. His mother, on the other hand, held strong communist views and could be described as “militant.”

The young Luigi Colani studied sculpture at the Berlin Arts Academy and later moved to Paris to study aerodynamics under Charles Deutsch at the Sorbonne. While in Paris, his first public work was sketching motorcycles for a sports magazine and later designed shoes for Dior and Chanel—he regards this period as being “bohemian” and a very satisfying era of his life. Despite numerous offers to design shoes for the fashion industry he opted to move to California, taking a job at McDonnell-Douglas in their New Materials Department. His work there led to a familiarization with many new synthetic materials and how they could be applied into various forms. This knowledge and education was paramount to his later design work.

Photo: John Colley

In the mid-1950s, Colani returned to Berlin and undertook work with Karosserie Friedrich Rometsch designing a concept car, the Fiat 1100 TV, which was displayed at the Geneva Motor Salon and awarded the Gold Rose. Fiat ordered 20 of these cars, but little was heard of them until years later when many Fiat models took on the design style of the prototype. He then designed the Colani BMW 700 delivering them with the first monocoque “kit-car.” In 1957, Colani worked with the great Carlo Abarth in Turin, where they both shared an obsession for sleek and flowing designs. Colani was commissioned to build an experimental aerodynamic car based upon an Alfa Romeo Giulietta Spider. The result bore all the hallmarks of Colani intermingled with much of Abarth’s styling principals. The rear of the car was quite sophisticated in that attention was paid to airflow under the car—lateral and heady thinking in those days, but time has shown it was the way to go. Weighing in at 780 kilograms, the 1300-cc car gave around 110 bhp. It became the first GT car the lap to 14-mile Nürburgring circuit in under 10 minutes, with a top speed of 130 mph.

Colani went from strength to strength, although many thought his works were objet d’art rather than having any practical use. Colani simply suggested his detractors had an inability to look outside the box of common thinking and failed to accept change. Hennerici appreciated Colani’s attributes, recognizing him as a very talented individual and hired him—it also didn’t hurt that he was German too.

Rolf Stommelen

Photo: Maureen Magee

With German financial backing, a German designer, a German driver was the missing ingredient. As has been mentioned previously, Hennerici had seen and indeed invested in the young Rolf Stommelen, who had been racing for a number of years, initially with his own privately entered Porsche 904 GTS. In the mid-1960s, Stommelen was invited to race for the Porsche factory team in long-distance events. He won the 1967 Targa Florio with Paul Hawkins, and in 1968 went on to victory at the Daytona 24 Hours and the Paris 1000 Kilometers. In 1967, he put the Porsche 910/6 K on the class pole for the Le Mans 24 Hours. His climb into F1 started in 1970 with a works Brabham BT33 sponsored by Auto Motor und Sport, alongside the master, Jack Brabham. With a couple of podiums in his rookie season and finishing 11th in the Drivers Championship, he was going in the right direction. He also campaigned the F2 Championship in an Eifelland-sponsored March, and drove for the Alfa Romeo sportscar team in that busy season as well. So, in 1971, looking to build on his F1 success, Stommelen joined the Surtees/Rob Walker F1 team. Unfortunately, the relationship soured as results failed to reach expected levels, finishing the season in 18th place. Gunther Hennerici saw no prospect of investing in a driver who’d lost confidence in his racing team. The decision was therefore taken for Eifelland to enter the Formula One World Championship with Rolf Stommelen as the works driver for 1972 —the first regular German GP driver since Wolfgang von Trips.

Eifelland Prepares for Formula One

With nearly all the pieces in place for an assault on the Formula One World Championship, only a key item was absent—the chassis, including engine and gearbox. Hennerici was hoping to use Francis McNamara, who’d previously built Formula Vee and Formula Three cars. McNamara’s team worked with Andy Granatelli to build an Indycar for Mario Andretti to compete in the 1970 Indy 500, and also modified Andretti’s STP March 701. By 1971, McNamara had gone bankrupt and his Austrian designer, Jo Karasek, was looking for work. Hennerici thought Karasek was the ideal candidate to design the chassis for the new Eifelland. Talks with Hennerici, Karasek, Ford Cologne and Ford Europe were very advanced by the latter part of 1971, and for once an F1 project wasn’t looking for money, the budget was already in place. The car was to be built at Mayen, in a workshop at the rear of the Eifelland Wöhnwagenbau factory—one of three across Germany. Although cash rich, the project was time poor. Negotiations between the various parties failed to find a consensus and way forward. With time running out, only Hennerici and Ford Cologne remained at the table, Ford Cologne provided the engines, and a rather disgruntled Hennerici was left to purchase a customer car from March Engineering, Bicester, England.

Photos: Pete Austin

March had produced the first customer F1 cars in 1970, and although they hadn’t been too successful there was a kind of promise shown. With aerodynamicist Frank Costin on board for 1971, March was confident of making headway in its second season. Unlike today’s F1, at that time designers were relatively free and not hindered too much by regulations. Colin Chapman’s Lotus 72 wedge-shaped contender reinforced the view that cars were not restricted by the conventional cigar shape—Derek Gardner’s new Tyrrell also broke new ground as did the Costin-influenced March 711 with its round nose and “Spitfire-esque” tea-tray front wing. March improved on its initial season, making reasonable progress in 1971.

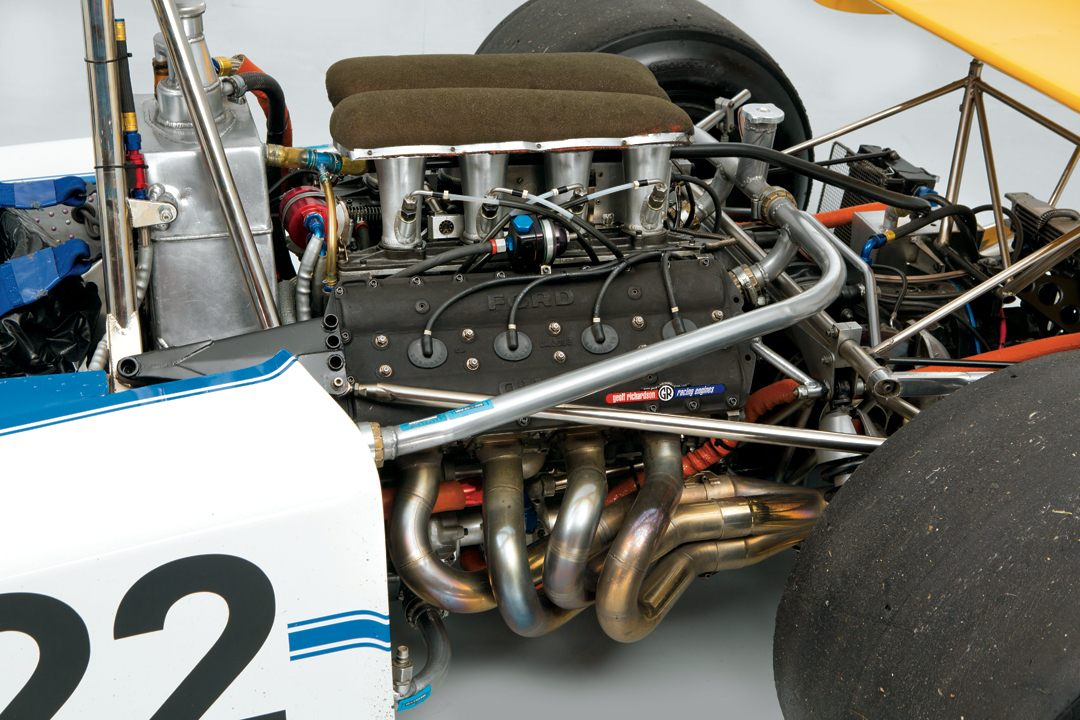

The March 721 was more of a back-to-basics car, at least as far as the customer cars were concerned. Nevertheless, as can be read in this month’s “Legends,” March was all at sea with its works 712X cars, dumping the “new thinking” for the F2-based 712G. Having purchased March chassis 721-4, Eifelland registered its team with the FIA as Eifelland Wöhnwagenbau, and the car as an Eifelland Ford Type 21, which understandably angered Robin Herd and his Bicester team. Whatever the body style or design, the car remained a March in Eifelland clothing.

Luigi Colani’s thought process and styling philosophy was to create and characterize in a way nature intended. In an interview, he described his view quite eloquently: “We evolve on a round planet, all that surrounds us is curvilinear, therefore I don’t see why we should detach ourselves from our environment, hiding behind straight lines and sharp corners that correspond to nothing. I’ve come to a pretty certain conclusion. Nature sculpts perfect designs. I’ve spent hours, weeks and even months observing nature. It reaches perfection over millions of years of evolution, by modifying, adapting itself little by little. Take a shark for instance; its forms haven’t changed for millions of years, a perfection, totally adapted to the aquatic environment. There’s nothing better.”

Photo: Chris Willows

Like those designers from an aviation background (Colin Chapman and Frank Costin), Colani’s designs were steeped in aerodynamic practices and principles. His patented work “C-form” explored a rationale that later racing car designers would describe as ground-effects. Colani’s patent for this was registered in 1967, many years before it became a common practice within motor racing—truly a forward thinker. Prior to starting work on the new car, Colani purchased a March 711 from the Bicester team for £2,500 to get an understanding of the current standards.

Eifelland Type 21 is born and racing …

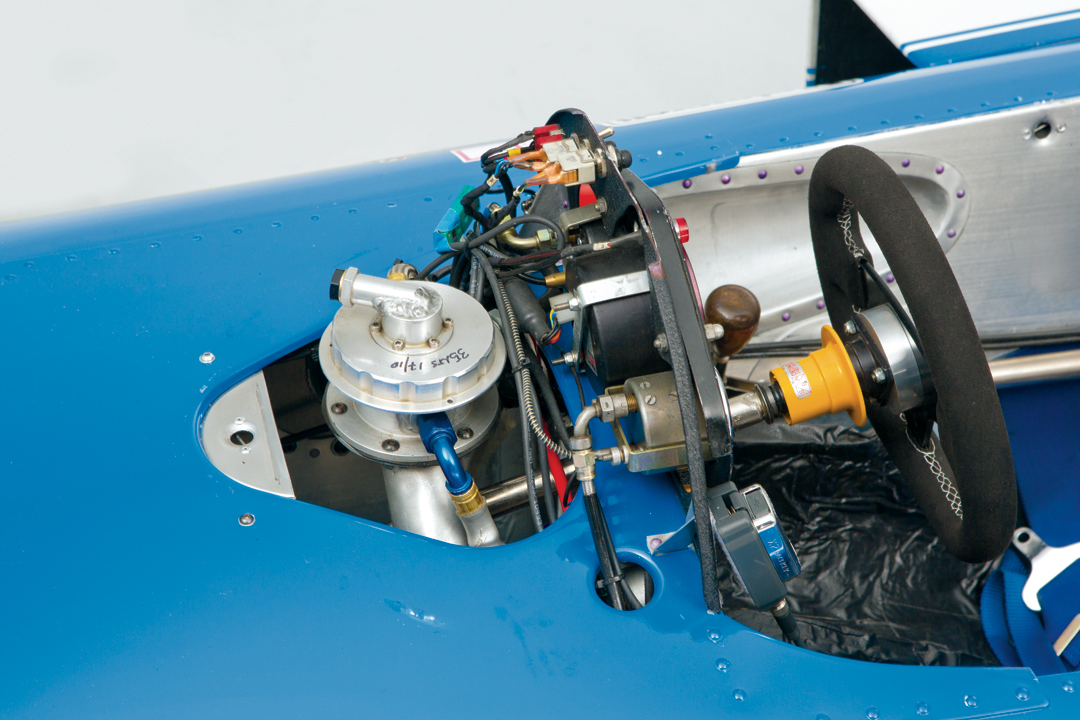

Given the foregoing, it came as no surprise when Colani unveiled his first incarnation at a rather damp Hockenheim—it was truly radical and futuristic in its styling. The car in essence gave an appearance of an open-wheeled sportscar with all enveloping bodywork from the nose to the rear wing. Breaking with convention, the airbox was centrally mounted, low down and forming part of the cockpit surround. A striking move away from standard practices too was the centrally mounted, periscope fashion, rear view mirror. Colani is reported to have been “cock-a-hoop” at the media launch and attacking and smearing current motor racing designers for being un-inspirational and having no clue of aerodynamics.

The first major testing was done in intense heat at South Africa’s Kyalami circuit, prior to the second Grand Prix of the new season, but Gunther Hennerici was absent from the race as disaster had struck at his Eifelland Wöhnwagenbau works. Two of the factories had been totally destroyed by fire. As team manager Heinz Koblitschek took control, heat of a different nature was causing initial car setbacks. With the dramatic all-enveloping bodywork there was little room for ventilation or any allowance for the engine to breathe, or cool. On the plus side, the car was quick in a straight line, in fact one of the fastest on the straight and only beaten by Denny Hulme’s McLaren. The overheating problems weren’t present on that cold and wet launch day at Hockenheim—maybe an oversight by the great Colani? He’d concentrated too much on aerodynamics and ignored ambient or other outside influences. In the race, Stommelen somehow managed to drag the car home to 13th place, a plucky finish from a lowly 25th grid place of 27 cars.

… but the project is thwarted.

Photo: David Shaw Collection

The factory fires had a devastating effect on the racing team. The large budget earmarked for a great Grand Prix campaign was now required to help save the business. Nonetheless, the team soldiered on to the next races, first at the non-championship Race of Champions at Brands Hatch, just a couple of weeks after the South African GP. As the car was wheeled out for first practice, much of the Colani bodywork had gone and replaced with more conventional panels. Stommelen finished the race in 12th place —the same position he’d started from the grid. For the Spanish GP at Jarama, once again new bodywork and new paintwork for the car as the team looked to make a step forward. Sadly, they were thwarted when they failed to show any pace. Qualifying on the penultimate row of the grid, by lap 17 Stommelen had lost control, spinning out of the race and crashing into a barrier. For the next two GPs, Monaco and Belgium, it was much the same story—although the car was finishing in classified positions—10th at a rain-drenched Monte Carlo (so, no mean feat for Stommelen to finish that race) and 11th at Nivelles, in Belgium. By the French GP, Gunther Hennerici had managed to sort his business affairs out by selling the remnants of his once powerful company to the window manufacturer Meeth Fensterfabrik. Unfortunately, the new owner of Eifelland Wöhnwagenbau, Josef Meeth, didn’t share the same passion and interest in motor sport as Hennerici. The French GP produced a lackluster performance with a 16th-place finish. The new owner had his Meeth Fenster company stickers on the placed engine cover as the car rolled up at Brands Hatch for the British GP. By this time, a creditable 10th-place finish was not enough to keep the new owner from walking away. Rolf Stommelen was handed the team, lock, stock and barrel—no payment was involved, Josef Meeth owner of Meeth Fensterfabrik Gmbh simply wanted to wash his hands of a project that by its very nature hemorrhaged money.

The end is nigh – enter John Watson.

While Stommelen managed to compete in both the German and Austrian GPs, he knew his time as team owner and driver were numbered. He had little or no money to carry on, and finished his home race with a retirement due to electrical problems after just six laps. Believe it or not, this was the first time the car had broken down with mechanical issues—a glimmer of achievement for the rookie team. Despite another classified finish at the Österreichring, the 15th place was the last hoorah for the Eifelland Racing team. Cash strapped and with no sponsors, Stommelen had little choice but to withdraw from the championship. While the German press had many criticisms for their home driver, German racing fans took him to their heart—he was flying the flag for the mother country. It was, therefore, an unhappy finish to a project that had started with such great enthusiasm—where have we heard that tale before?

Waiting in the wings was a wily fox, a certain Mr. Bernard Charles Ecclestone, who purchased the car and all the kit from Rolf Stommelen for an undisclosed fee. The car was subsequently sold to John “Monkey” Brown, an Irish motor trader. It was to give John Watson his first taste of F1 machinery. I’ll let John take up the story,

Photo: Simon Lewis Transport Books

“Tony ‘Monkey’ Brown was an Irish car dealer, based in London. I’m not too sure where the ‘Monkey’ bit came from, but he was a bloody good dealer, I can tell you that. To look at you’d not think he was a car dealer with his long hair, moustache and that sort of thing. He regularly bought and sold stuff and generally traded with Bernie Ecclestone. God only knows why ‘Monkey’ Brown did this deal with Bernie to buy the Eifelland. I got a phone call from this guy, quite out of the blue, to ask if I’d like to drive the car at Phoenix Park. I’d previously raced at Phoenix Park; indeed I won the race in 1967, ’68 and ’69. It was a pretty special moment for me to drive my first F1 car—albeit at the most dangerous racetrack in the world. Phoenix Park has a great history, first racing done there in the 1920s.

“So, I drove the car at Phoenix Park, Ireland, it was in a Formula Libre race. I remember the car rocked up at the circuit on the back of a Bedford TK lorry, late on the Saturday. At that time, it still had the strange Colani bodywork on it. Many people have asked the question, ‘what was the center rear view mirror like?’ Well, my helmet was made by Bell, it had a center bar rather than a full opening. I think Jacky Ickx came up with the original design, it was to add more facial protection should we collide with the catch fencing—a safety device around most circuits during the 1970s. So, because of the helmet design I never really saw it. As a racing driver, your vision is so much further down the road than a couple of inches from your eyes, it really made no difference to me. Our first job was to get the car started. It was an art in itself to do. Foolhardy on my part, I assumed that being a Formula One car it would be a properly prepared car. I jumped into it and set off. I drove it until something went wrong and I retired. That was it.

“A month further down the road, I think ‘Monkey’ sold it to Paul Michaels at Hexagon Racing. Hexagon had been racing in historic racing fielding D-Type Jaguars, Maserati Birdcages and the like. At the time, it’s right to say a 1970s F1 car wasn’t too much different to anything else. They were ‘mechanical beings’ rather than the nightmare F1 cars are today. They took it into their workshops at Highgate, it was in appalling condition, but they worked hard on it and it became a more conventional looking March F1 car devoid of all the Colani nonsense. On reflection, I think I was fortunate that nothing fell off the car when I first took it out.

Photo: McKlein raceandrally.com

“Hexagon Racing Team entered the rebuilt car for me to drive at Brands Hatch in the John Player Challenge Trophy race—an end of season celebration, non-championship event. The car went well, I qualified in the top third of the grid (made up of F1 and F5000 cars) and had a great race finishing 6th behind Beltoise, Pace, de Adamich, Schuppan and Peter Gethin. Although, through lack of experience in F1, I’d had no real judgement I could make on the car, I thought both the car and I performed perfectly well. I’d finished ahead of a great deal of regular top drivers. The whole thing was regarded as a success by Hexagon, ‘Monkey’ and, of course, the onlooking Bernie Ecclestone—who had a hand, not in his pocket, but on most things. It was no accident that I was signed up by Bernie to do a full season of F2 racing for him in 1973. It was from that drive that Hexagon became an entrant in F1 in 1974 with the Hexagon Brabham.

“It has to be acknowledged that Luigi Colani was a designer ahead of his time in many respects. His concept was an interesting design. It was something no one else had looked at, quite unique. Whether it would, or could have been made into something better is debatable. It certainly was good on straight-line speed due to its aerodynamics. Since then he’s designed many other things unrelated to the automotive industry, like furniture, and become renowned and celebrated for a lifetime of work and achievement.”

Driving the Eifelland Type 21

The car has gone through a few hands since that first season in 1972. During 2015, the current owner purchased the car to compete at the 2016 Monaco Historique Grand Prix. A decision was taken to restore the car to the way it was originally entered for the 1972 Monaco GP. So, this unique car resplendent in period livery returns to the “jewel in the crown” circuit at Monte Carlo. We’re fortunate that the Mediterranean sunshine is beaming down on us—unlike race day in ’72 when the heavens opened. Looking at the car, it’s relatively easy to understand the radical design, but this is with a wealth of knowledge gained over a further 40-plus years of motor racing history. It’s also not too difficult to understand some of the problems encountered in period. I’m sure Mr. Colani would make significant improvements should he be asked to contribute today. It has to be said, that the free spirit and radical thinking of a man such as Luigi Colani would be suffocated within the strict rules and regulations governing today’s Formula One World Championship.

While outwardly the car looks unique, sitting in the cockpit is like climbing aboard any other conventional F1 of the period—indeed, it’s a March! The sides of the cockpit are higher than a normal F1 car of this period and it does have a tendency to make you feel a little claustrophobic at times—it takes a little getting used to. John Watson remarked that the centrally fitted rear view mirror caused him no problem when driving, but it does draw the eye when stationary. The restored air-intake and cockpit surround has had to be reconstructed as it outwardly appeared. Neither Colani, nor any records that survive from the team suggest how the air flowed once it entered the central duct. The new duct simply guides the flow toward the engine rather than compressing it in any way. With the car prepared, started and completing a couple of installation laps it’s time to try a flying lap. Things of note in the preparatory laps are firstly, the amount of noise emanating from the Ford DFV engine located inches from the back of your skull. Second, while the rear view mirror caused no significant interruption of frontal view, it was restricted in vision, direct rear view was fine, but there is an inability to see who is coming up inside or outside. Remembering to keep the revs above 7,000 rpm is vital due to the lack of engine torque below that figure. The acceleration the engine provides is just something else and needs to be carefully harnessed—especially on such a tight circuit. The car is set rather neutral with a leaning toward understeer if anything, while the braking and gear shifting is excellent. The gears have very close ratios to second, third and fourth, with a little more of a gap to fifth—maybe a slight oversight given the drive uphill from Sainte Devote.

Now onto our test lap, as we exit the second gear Anthony Noghes complex we’re onto the start/finish straight, so it’s straight through the gears to fifth, reaching around 155 mph before the first braking point for Sainte Devote. The near 90-degree, second-gear, right-hander is a little difficult, the apex is blind as the road falls away prior to heading up the hill. While it offers a challenge it’s very satisfying to get this corner just right—fortunately, unlike the 1970s, there’s now an escape route if we’d got this wrong. Driving up the hill, we’re again through all the gears to fifth, flying as we take Beau Rivage and through to Massenet and Casino Square. Road markings are ideal reference points at Monaco, so braking for Massenet is at the road crossing. Due to the gear ratios, we’re able to take both Massenet and Casino in fourth. Downhill now to Mirabeau, taking care to avoid the hump on the left side, Mirabeau offers great road camber, getting the braking right here feels like the corner has “hooked you up” and you’re on rails through it in second and squirting the accelerator pedal to the old Lowes Hairpin—another iconic corner—staying in second gear we hug the entry. Care has to be taken here due to the limited amount of lock on the steering. It’s a matter of using accelerator and brake to assist a good passage to the next right-hander, the first Portier, and onto the second Portier, another right, leading to the entrance of the tunnel. This is probably the hardest corner of the entire circuit, it looks like a 90-degree bend, but it’s more like 120 in reality. As you turn in you’re tempted to accelerate, but you have to wait for the corner to finish unwinding before you do.

By the time you put your right foot down again you believe you could have gone quicker, but you couldn’t—it really messes with your mind. It’s back full on the throttle to the tunnel, which is a long right-hand curve that seems to go on forever—some say it’s flat, especially the professionals. We’re nearly flat, around 130 mph in fifth as we exit the tunnel on the downhill section toward the chicane. From an armchair enthusiast’s perspective, this section of the circuit offers no real challenge. In reality, it’s a steep downhill section with an unforgiving road surface and a steep curb to the right, the ideal racing line. Many an experienced driver has completely lost it here. The 150 and 100 boards come into sight, hard braking at the 100 and down to second as quick as you can. Your eyes are on stalks here, looking for the left apex, then flick with the steering immediately right when the marshal’s post comes into full view. Driving through here, it almost feels as though you’re going to take the marshals out, but it’s an optical illusion. Again, avoid the curbs here—it can spell disaster! Now we’re heading toward Tabac, changing up as we go. It’s also a point where you can feel the crowd is part of the circuit, just like a stadium section.

Tabac is a strange left-hander, we’ve braked and changed down at the 50 marker board, but the corner flares out on exit—it’s here where you especially have to feel at one with the car to keep your lap flowing. Thinking too hard can cause you to have problems. Piscine is the next to negotiate a quick left-right before the swimming pool. We’re on the corner before we see the apex, then we’re immediately looking right for the other apex—again, you’re on it before you know. The exit, by comparison, is great, and takes us on the short straight. The next right-hander has been re-profiled to give an easier and gentler entry; it’s a quick move to the left as we take the curve prior to La Rascasse. We can hit the curb here, in fact, it helps you through the corner if you do. La Rascasse is totally blind and the exit has an uphill gradient. A last-minute dab on the brakes to scrub the speed off is required here—too tight and you’ll hit the Armco. You also have to consider the rear track is four or five inches wider than the front. If the front is tight you’ll certainly catch the back…so, caution! We’re in second gear and squirt the throttle uphill driving past the pit lane entry on the right and toward the Anthony Noghes complex, taking us back to the start/finish straight. It’s a great feeling, to have completed the lap – challenging, but a great buzz when it turns out right.

Conclusion

Over a near 70-year history, Formula One has had its fair share of mavericks, and dreamers—Eifelland was such a team. The brash and out-spoken sculptor, Luigi Colani, thought his ideal design would make other F1 contenders overnight antiques. Despite his back-to-nature thinking and his work in the aero industry, he found that F1 design is more complex than going fast in a straight line. Many parts of the car have to work in splendid harmony to be successful. Gunther Hennerici, the romantic fantasist, in the mold of Ken Tyrrell and Rob Walker, daring to take on motor racing’s establishment for national pride—unfortunately, suffering severe financial ruin almost before the car hit the track—and Rolf Stommelen unable to convert all his sportscar driving mastery into a competitive F1 challenge, all conspired to the downfall of the Eifelland Team. It’s worth asking this question though, without that failure would John Watson have got his F1 baptism?

SPECIFICATIONS

Wheelbase: 2560-mm

Length: 4270-mm

Width: 2090-mm

Height: 990-mm

Weight: 550-kgs

Track: Front: 1580-mm, Rear: 1620-mm

Suspension: Front: Double wishbone coil over spring, Rear: Reversed lower wishbones; single top link

Engine: Ford Cosworth DFV 2993-cc

Gearbox: Hewland FG400

Brakes: Girling: Front 4pot CP 2661 vented, Rear 2pot AR3 vented

Steering: Rack and pinion

Wheels: Cast Magnesium, Front: 11 x 13, Rear: 17 x 13

Tires: Avon

Resources/Acknowledgements

“Colani” by Philippe Pernodet & Bruce Mehly

“The Story of March” by Mike Lawrence

“A-Z of Formula Racing Cars” by David Hodges

“March – The Grand Prix and Indy Cars” by Alan Henry

“Grand Prix Who’s Who” by Steve Small

“Motor Racing Year 1973” by MRP

“History of the Grand Prix Car 1966-1991” by Doug Nye

“The Forgotten Races” by Chris Ellard

Vintage Racecar would like to express sincere thanks to the following for their assistance with this piece:

• Dave Shaw for allowing us to profile the car

• Liaz Jakhara of Zul Racing for allowing us to use his works premises

• John Colley for the studio photography

• Gilles Bouvier Photosports for the Monaco photography

• Pete Austin and Peter Collins for current and period photos

• …and last but not least Blyton Park Driving Centre.