1965 Lola T60-Cosworth SCA

Since the birth of the Formula One Championship, in 1950, there has been a ladder for potential Grand Prix drivers to climb to qualify, or rather amass the necessary skill set/finance, to be able to race at the top level. Obviously, like all things, there have been notable exceptions along the way, but for the most part, drivers have begun their professional racing careers in junior formulae progressing step by step to the highest echelon of the sport. During that course of time, for so many reasons, countless numbers of men (and to a lesser extent women) have fallen by the wayside realizing they don’t have what it takes, or get that lucky break, to be part of the hallowed Formula One circus. Some of that group become great drivers in other disciplines of our sport, while inevitably others fall away completely. Along that path, motor racing enthusiasts have witnessed this very public natural selection process, which continues to this day. However, it has to be said in the current era, for far more than a handful of years, finance rather than pure driving technique seems to be the ultimate attribute to ascend the ladder.

Nearing the top, drivers used to advance from the junior ranks via Formula 3 and Formula 2 to be eligible to drive in Formula One. While the Formula One series has kept its name throughout, Formula 3 and Formula 2 have had gone through a good number of changes and rebranding along the way, which have confused many. Thankfully, since the 2017 Bahrain GP, Mr. Chase Carey, now in charge of Grand Prix racing, and his team have seen sense and reverted back to the tried and tested notations, so Formula 3 and Formula 2 are alive and kicking once again. There are many who have commented that the 2017 Formula 2 season, while a one make series—a Dallara chassis powered by 4-liter Mechachrome V8 engine— proved to be some of the best entertainment during the course of a Grand Prix weekend, despite being dominated by the Monégasque driver Charles Leclerc who’ll naturally elevate to Formula One joining the Sauber team for 2018.

Formula 2, 1964–1966

For the purpose of this profile, we look back just over two generations to the mid-1960s and the Formula 2 series of that era. In those days, while motor racing had always been an expensive activity, the financial qualification of a driver was spelled with a lower case “f” and intense, but friendly competition of racing was a sport spelled with a capital “S”. Like other formulae, over the years Formula 2 has adopted and adapted changing regulations including engine power set by the Commission Sportive Internationale (CSI), known today as the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA). Almost forgotten these days, but from the 1964 through to the 1966 seasons, Formula 2 cars ran with 1000-cc engines. Indeed, as Formula One was restricted to 1,500-cc engines until the return of power in 1966. Formula 2 chassis were simply small-scale Grand Prix cars, or one-off cars built specifically for the purpose. In an era when racing drivers were almost like jockeys at a horseracing meeting, jumping from mount to mount, it wasn’t beyond the norm to see both budding and established stars competing against each other. The likes of Clark, Hill, Surtees and Brabham, by then all World Champions would vie against Attwood, Gardner, Hawkins and Spence – drivers to yet make a name for themselves. No wonder the races were crowd pleasers, but motor racing had established itself as an entertainment and start/finish money was paid prior to the now resident evil of sponsorship, which many blame for the demise and politicking of the majority of today’s sports.

The now “forgotten formula” kicked off on April 5th, 1964 at Pau, France for the 80-lap Grand Prix of Pau, with a 17-car field of now very famous names and faces all vying for victory. Almost inevitably, Jim Clark won the “round the houses” race in his Lotus 32 entered by Ron Harris, teammate Peter Arundell was 3rd in a Lotus 27. Sandwiched between the Lotus boys was Richard Attwood in the Wolverhampton-based, Midland Racing Partnership’s Lola T54. MRP is the stable of our profile car and Attwood did a fine job for him and the team to finish just a shade over a second behind Clark. The T54 was simply a Formula Junior chassis with a 997-cc Ford SCA powerplant and, despite being a dated design, it was always reasonably competitive with more than a handful of podium finishes throughout the season.

New for 1965 was the Lola T60, a monocoque car, in line with the then current thinking of the day. Despite having aerodynamically good clean lines it really didn’t take the promised fight to the likes of the Brabham BT16, or the Lotus 35, although the early signs and performances were good. It has to be said though, that 1965 was the Midland Racing Partnership team’s most successful year with a 1-2 at Vallelunga, with Richard Attwood and Tony Maggs, a win for Chris Amon at Solitude and a further victory at Oulton Park with John Surtees at the wheel. A well-earned and dramatic 2nd place was gained by Frank Gardner and 3rd at Karlskoga, for Jo Bonnier. The Reims race was a fantastic spectacle being one of the closest finishes ever seen. After one hour and 33 minutes, less than a second covered the first four cars, with the final order being Rindt, Gardner, Clark, and Rees in the second Winkelmann Brabham.

The first round of the 1965 series, the BARC 200 for the “Senior Service Trophy” on the 20th of March, 1965, threw up a surprise with Mike Costin in a Brabham BT10 leading, however, the planned 43-lap race had been abandoned on lap 18 due to heavy rain and a water logged track – no points were given for this event as the distance covered didn’t qualify as a race, or even part race distance. Notably in 2nd and 3rd places with equal times were Jim Clark (Lotus) and Richard Attwood (Lola). Just a couple of weeks later at the Spring Trophy, Oulton Park, Attwood put the T60 on pole! Unfortunately, an errant gearbox let him down in the race causing him to retire very early from the 40-lap contest. Hulme took the flag in the Brabham BT16, but champion Jim Clark once again dominated the season in his Ron Harris entered Lotus 35. The Midland Racing Partnership team finished a very creditable 3rd in the overall French Formula 2 series standings for the season, behind the Championship-winner, Ron Harris – Team Lotus and 2nd place Roy Winklemann Racing. Richard Atwood scored 8 points in the British Championship, just one point behind John Surtees.

Formula 2, in 1966, was all Brabham with the Honda-powered BT21, with Jack taking an overall total of ten wins and teammate Denis Hulme two – although Hulme finished 3rd in the final standings, as Jim Clark had a better score of lower placed finishes. The final curtain came down on the 1000-cc Formula 2 “screamers” at Brands Hatch, on the 30th of October, 1966. While much has been written about many of the participating and victorious cars and drivers of that era of screamers, little has been recorded of the Lola T60, in particular chassis SL60/2, which has had a fascinating life.

Lola T60, Chassis SL60/2

Period MRP mechanic, Roger Fowler, now owns the car that he serviced for the race team. So, it is only right and proper that he now takes over the telling of the life story of SL60/2.

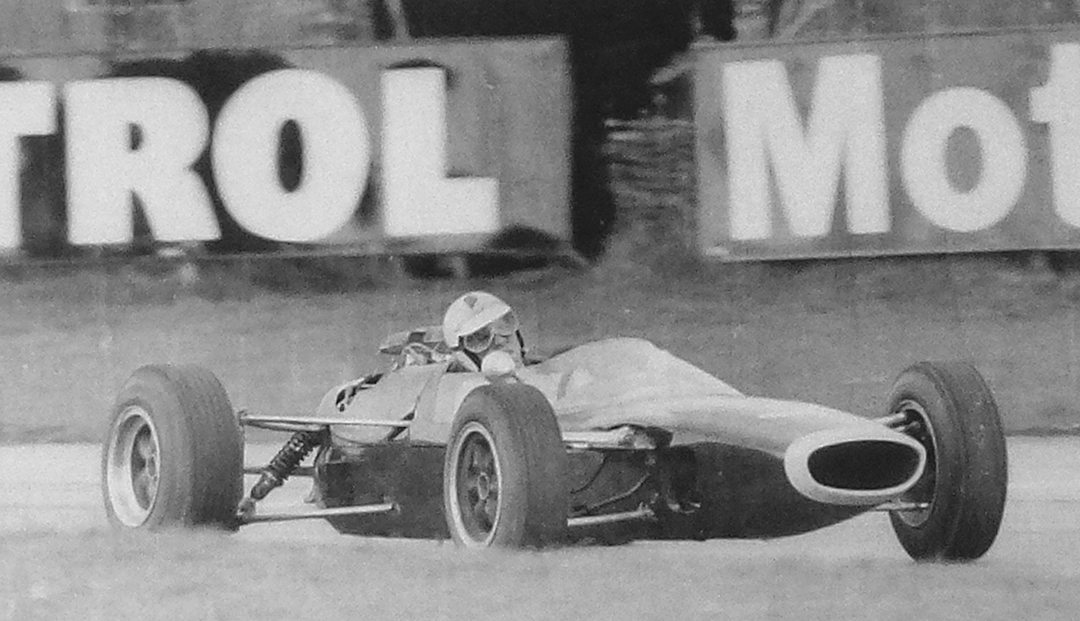

Photo: Derek Hill Archive

As denoted by its chassis number prefix it was built at Lola’s Slough factory over the winter of 1964/’65 and was the second monocoque single-seater the company had built. Tony Southgate carried out the majority of the design work as Eric Broadley was committed to the lucrative T70 Can-Am project. There has been some controversy over the exact number made of the T60/T61/T62 series, with figures of 11, or 12 suggested. Rob Shanahan who is rebuilding Chassis No. 4 in America has done a lot of research on this, and we know that the third car built, SL60/3 was fitted with a fuel injected SCA early in 1966 and re-numbered SL61/6, thus a total of 11 Formula 2 and Formula 3 cars would seem correct.

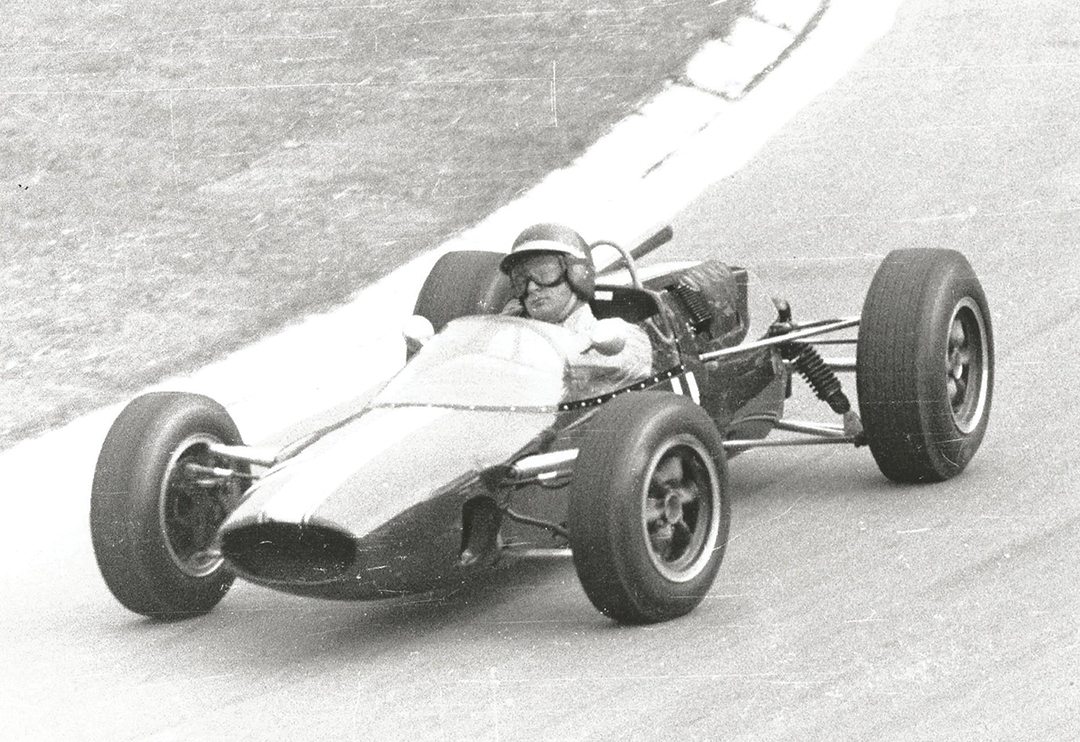

The minimum weight limit for the new 1-liter Formula 2 introduced in 1964 was a relatively high 420-kg, allowing Lola to build the tubs for their new cars out of folded 18-gauge mild steel sheet, which was cheaper and stiffer than aluminum. The first car’s tub was of mainly riveted construction, which was sealed and the fuel poured directly into it. As Colin Chapman discovered with his early Elites, this was not a good idea as fuel tended to leak out particularly from around the gear lever area. So the tub of SL60/2 was spot welded and made 3.5” longer with bladder tanks employed to give the same capacity. Rocker actuated inboard front suspension is used much like the Lotus 25 and 33, and the fairly “beefy” rocker arm is paired with a conventional lower wishbone and a small non-adjustable anti-roll bar. The conventional outboard rear suspension features top and bottom radius arms, an inverted lower wishbone, and a single lateral top link. The rear anti-roll bar is adjustable as are the front and rear Armstrong dampers.

Photo: Ferret Fotographics

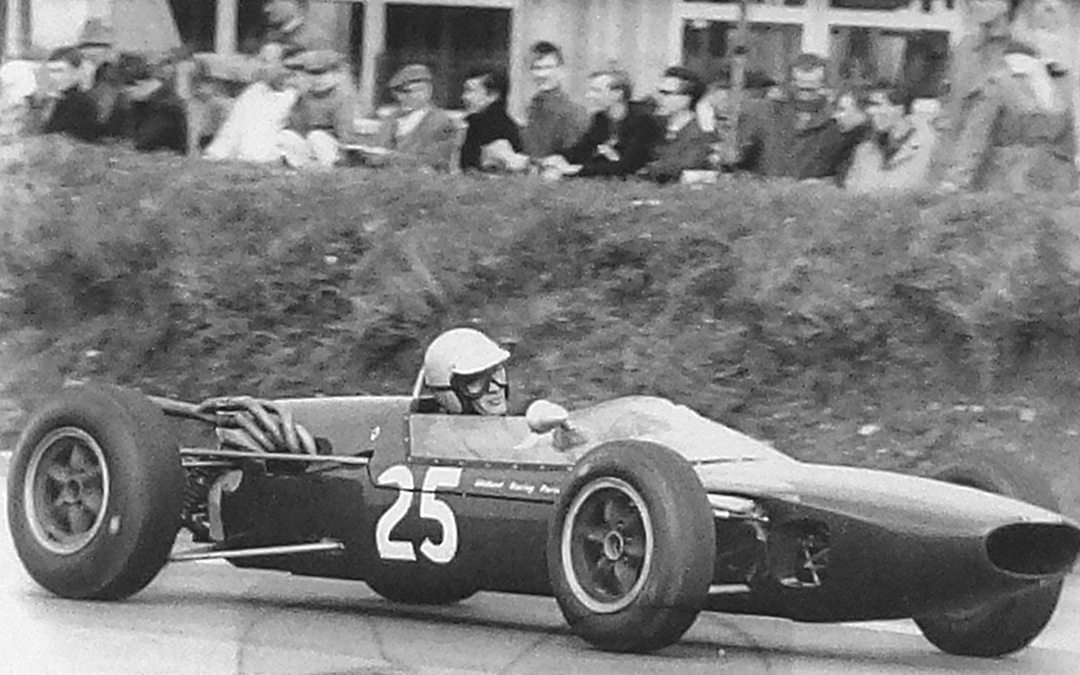

Run by Midland Racing Partnership (MRP), the official Lola factory team for International Formula 2 racing, it was initially fitted with a fuel injected BRM type 71, twin-cam engine, and made its race debut in the hands of Tony Maggs at Snetterton for the Autocar Trophy in March 1965. Later, in mid-season, the BRM was swapped for an SCA. As has been already mentioned, in 1965 the Lola SL60/2 finished 2nd at Vallelunga and Reims and 3rd at Karlskoga.

Usually driven by Frank Gardner it was retained by MRP and run by them throughout 1966 with a fuel injected SCA, but the Brabham Hondas were all dominant and the team’s best result was a 4th place by David Hobbs at a rain soaked Barcelona. During the car’s front line Formula 2 career, other drivers included Chris Amon, Richard Attwood, Paul Hawkins, and David Hobbs. At the end of the year it was sold less engine and gearbox to Brian Nelson in Ireland.

New life for the Lola

For its new life in Formula Libre, Nelson fitted a Lotus twin-cam engine together with a Hewland FT200 box and raced successfully for three years to the end of 1969. From him it passed to a now defunct company called D & A Shells in London who made fiberglass car bodies amongst other things. New Zealander Keith Laney became the next owner in 1972. After some use in the UK, he shipped it home to Christchurch, but it appears the car was damaged in transit. In a letter on file to Eric Broadley dated November 6th, Laney states that “the car is Chassis No. SL60/2, is in original condition, and that he would like to purchase a replacement windscreen and four new wheels.” His stated intention was to race the car in the NZ National series.

In 1976, he sold it to fellow New Zealander, Mr. Henry Holt. Mr. Holt was obviously a man of exquisite taste as it’s recorded that he had the car hanging on the lounge wall of his house as decoration! The story goes that a tax issue caused his hurried departure to Australia and that he left with the Lola strapped to the deck of his yacht! How much truth there is in this tale is not known. What is certain is that by late 1977 the car was in the hands of an Australian movie producer named Matt Carroll, who wrote in December of that year seeking information from Mike Blanchet of Lola Cars. At this time, it had a side-draft 1100-cc Cosworth Ford engine and sported 8-inch and 10-inch wheels. By May 1978, he had changed the engine to a Cosworth 1-liter MAE, and registered the car with the Confederation of Australian Motor Sport (CAMS). Carroll kept the Lola for several years racing it with the MAE until 1985, before selling it to a Mr. Don Black of Galston, New South Wales.

Numerous letters from Black are on file including lengthy correspondence between him and Bill Bradley, one of the original MRP Partners. From his records, Bill provided detailed information on the different Lolas owned by the Partnership, and who drove which; all making most interesting reading. It appears that from early in his ownership, Don Black decided to try and obtain an original SCA to return the car to true Formula 2 spec. To this end he wrote to Cosworth Engineering asking if they knew where he could obtain one. They in turn, put him in touch with John Fenning who subsequently supplied an SCA and some of the parts to rebuild it. However, it seems there were lengthy delays with the installation, and in the meantime, Don fitted a 1600 twin-cam and raced the car in this form up to September 1994. The SCA project was never fully completed as, due to illness, Don lost interest and eventually offered the T60 for sale in 2001. A deal was agreed with one-time saloon car racer Rob Tweedie of Sydney who became the new owner; which brings me back to the start of this story.

As explained earlier, he decided to restore the Lola, and over the course of the next five years it was stripped down and the rebuilt SCA engine was properly installed. A launch party at which Frank Gardner was guest of honor took place upon completion of the newly rebuilt car in mid 2006, and it returned to the tracks in the hands of son Tom Tweedie. It created a lot of interest, but there was no obvious category for it in Australia, which was the main reason Rob eventually decided to sell. Also, as he explained, was the fact that he couldn’t fit into it!

On arrival back in its homeland, in July 2013, it came with a vanload of spare body sections and moulds, wheels, engine parts etc., and the aforementioned documentation. It was a great feeling to just look at it standing in my garage. Never in my wildest dreams had I imagined owning one of the old MRP team cars. It took me a while to go through everything but gradually I sorted it all out and began to take stock. Thankfully, the car was basically very original and unmolested, and due no doubt to its long sojourn in the benign Australian climate there was no rust, or rot in the monocoque tub. Valuable references were the numerous period photographs I had collected over the years, and particularly useful was a 1966 “Motor Racing” track test showing the car without its bodywork. Another valuable find on an American photo site was a brilliant frontal color shot of Jo Bonnier in the car in Sweden. This was also less the body so revealing all the suspension, steering, brakes etc. This sort of photo is invaluable to a restorer. Although Rob Tweedie and his team had carried out a workmanlike restoration there were numerous details that were incorrect. The most obvious of these being that the tub was painted black. In period they were always a pale grey color. To put this right, of course, meant a complete strip down, but I wanted to get the car as near as possible to how I remembered it. Another factor to consider was the raising of the roll over bar to comply with current regulations, which could be done at the same time.

Driving SL60/2

Our driving impressions of the Lola were made during a “shake-down” test at Castle Combe racing circuit. Situated about 20 miles east of Bristol, Castle Combe is in the county of Wiltshire. Like many of the racing circuits in the UK it was a World War II airfield, now converted to racing around the almost 2-mile former perimeter track. Opening in 1950, it has attracted many forms of motor racing and has attracted many stars of former eras of the sport, including Peter Collins, Mike Hawthorn and Stirling Moss. The circuit layout has changed little in the years since it opened, apart from the necessary upgrades for safety purposes. Similar to Goodwood, it’s a circuit that time almost forgot and a great favorite with many drivers.

It’s a relatively warm, sunny day with good visibility and a dry track – conditions near perfect for this first run in the recently restored Lola T60. As in period, the car has been warmed and fluids are up to temperature. With just a 997-cc engine to power away, it must be remembered that keeping a high rev range is imperative to performance. The sunrays glisten off of the dark blue MRP colored car with its distinctive yellow nose band. The yellow names “Amon, Attwood, Bonnier, Gardner, Hawkins, Hobbs and Maggs” positioned on the lower front, offside, side panel gives an idea of the provenance of the car’s early racing history. Comfortably seated in the cockpit, five dials are on the sparse dash, the two significant ones are easily seen through the top aperture of the three spoke steering wheel. A small diameter oil pressure gauge, with a red line marked at 45-lbs and the larger rev counter with – for this shakedown purpose – a red line marked at 10,000 rpm.

Engaging first gear—remembering to keep the revs up—and we’re away down the pit-lane and onto the circuit. The first lap or two are simply to get relaxed with the car, warm the brakes and ensure there are no gremlins lurking – so far, the only running the Cosworth SCA engine has done is on a dyno. As we cross the start/finish line we’re in sixth gear and up to around 130 mph, we’re probably at the fastest point of the circuit now, through Folly and toward a shallow right-left at Avon Rise. Dropping a couple of gears, Quarry Corner is a tight right, but is easily taken in third gear, back up to speed its along the short Farm Straight to The Esses another chicane, right-left, and again taken in third.

Thanks to the modern set-up procedure and wheel weighting—not available in period, at least not at MRP—the car seems perfectly balanced, with no sign of over, or understeer. Having said that, this is at shake down speed rather than racing mode, so it could be considered that we’re not being too aggressive. The brakes are responding exceptionally well and totally balanced, as is the steering that feels very direct. Almost two-thirds of the lap gone and it’s down to third again for Tower Corner, a 90° right turn. Again, we’re building speed towards Bobbies, another right-left chicane, but more open than The Esses. Having negotiated the last technical part of the lap we move through Westway and Dean Straight to the last corner of the lap. Camp Corner, a right-hand bend takes us back to the start/finish line where we build speed as soon as we’ve exited. It’s easy to see how the likes of Attwood, Gardner and Hawkins got their thrills out of racing this car and how a World Champion won the Oulton Park Gold Cup with it. It also shows how continued development in racing is the only way. Eric Broadley’s Lola F2 cars were indeed fit for purpose, but little time was spent on further development due to the more financially lucrative T70 program. With a shortage of funds, MRP did a great job preparing the cars for competition, but lacked the finance to improve the car into a regular race winning machine.

Specifications

Engine: 997-cc Cosworth, single overhead camsha , 4-cylinder, fi ed with 2 twin-choke, side draught Weber carburetors. Dry sump lubrica on.

Gearbox: Hewland 6-speed manual (various ra os) – rear wheel drive

Brakes: Girling discs brakes front and rear – 10-inch front, 91⁄2-inch rear.

Steering: Rack and pinion

Chassis: Monocoque construction

Body: Fiberglass

Suspension: Front and Rear – Double wishbone, telescopic shock absorbers, co-axial coil springs mounted inboard.

Wheels: 13-inch rim diameter, cast magnesium bolt-on wheels

Tyres: Front – 71⁄2-inch rim for 500 x 13 Dunlop res. Rear – 9-inch rim for 600 x 13 Dunlop res.

Width: 65 inches

Wheelbase: 88 inches

Track: 53 inches

Bibliography

A-Z of Formula Racing Cars by David Hodges 1964-1966 La Courte Histoire de la Formule 2

1000cc by Chris an naviaux Drive It! The complete book of Formula Two Motor Racing by Tristan

Wood Midland Racing Partnership – A Celebra on in Words and Pictures – Compiled by Derek Hill

Periodicals

Autosport, Motor Sport and Motor Racing

Thanks

Sincere thanks to Roger Fowler for allowing us to profile his car and supplying such detailed, informa ve and factual input. Thanks also to Derek Hill and Ferret Fotographics for period photos.

Click here to order either the printed version of this issue or a pdf download of the print version.