Heavy Industry

The Aston Martin brand was founded in 1914 by Robert Bamford and Lionel Martin, who started their automotive partnership together as Bamford and Martin, Ltd. in 1913. In its pre-war years, Aston Martin was known for constructing high-performance sports cars that got the most from their small displacement (under 2-liter) engines. Sadly, Aston was also known in these early years for a near constant succession of ownership changes, which by 1936, found the company in the ownership of the British Sutherland family.

reinforced with welded steel panels around the cowl—essentially aircraft monocoque construction. He fitted this forward-looking chassis with independent front suspension that utilized coil springs and long trailing arms, while the rear end featured a live axle suspended by coil springs and located by radius arms and a Panhard rod.

With the war over, the Sutherland family saw little opportunity in restarting the manufacture of automobiles in post-war Britain, and so put the assets of Aston Martin up for sale with an advert in the London Times! One of the potential suitors who expressed interest was David Brown, scion of Britain’s largest manufacturer of tractors and gear trains. Brown bought Aston Martin, in 1947, for a paltry £20,500, after driving Hill’s Atom and being impressed with the car’s handling. The following year, Brown was also able to purchase the Lagonda concern for £52,500, after it went into receivership. While Brown purchased the Lagonda name, factory and assets, he also received a new DOHC, 2.3-liter, inline 6-cylinder engine designed by Willie Watson, under the supervision of W.O. Bentley himself. This new LB6 engine would prove to be worth the value of the purchase, in its own right.

Birth of a Legend

In 1948, David Brown’s Aston Martin took the rolling chassis and 1,970-cc, inline 4-cylinder engine of the Atom and combined it with a new flowing body penned by Frank Feeley. Three examples were built to compete in the 1949 running of the 24 Hours of Le Mans and Spa. Two cars were equipped with Claude Hill’s small 4-cylinder engine, while a third received the Lagonda 2.3-liter inline-6. While the Lagonda-engined car retired at Le Mans, it came tantalizingly close to winning at Spa. This result, combined with Jaguar’s surprisingly enthusiastic reception for its new inline, 6-cylinder, XK120, led Brown to decide to switch production of his new Aston Martin sports car from the 4-cylinder engine, to the sexier 6-cylinder.

By 1953, it became clear that one of the DB2’s shortcomings was its lack of interior space and seating for more than two. As a result, in October of that year, Aston debuted the redesigned DB2/4, essentially the DB2 with a 7-inch longer 2+2 body that included a rear hatch for better access to luggage. Though the car’s weight increased to 2,600 pounds, this was offset by increasing the engine’s displacement to 2,992-cc. Between 1953 and 1954, 595 examples of this first series DB2/4 were built, including some nine rolling chassis that would make their way to Italy for custom coachwork.

Allemano

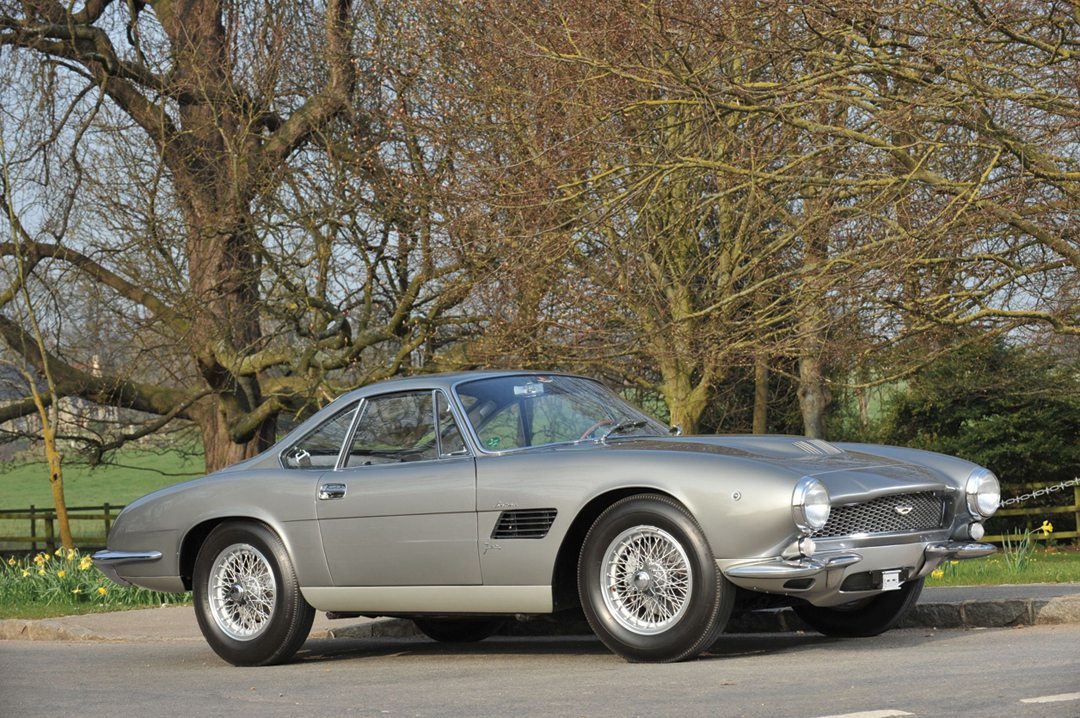

In 1953, a Series I, DB2/4 rolling chassis (LML/761), equipped with 3-liter DB3 engine, was sold directly to a J. O’Hara of Casablanca. Mr. O’Hara was a personal friend of David Brown and elected to have his chassis shipped to Ghia in Torino. However, Ghia was unable to get to the Aston in a timely manner, so O’Hara had the chassis moved to the carrozzeria of Serafino Allemano, for coachwork. There it was given a berlinetta body designed by Giovanni Savonuzzi, who would a few years later design another unique, one-off Aston. Savonuzzi’s clean, fastback design, with large wraparound rear window, was an elegant interpretation of the DB2/4 form and would serve as a remarkable prelude to the DB4, still some five years off in the future.

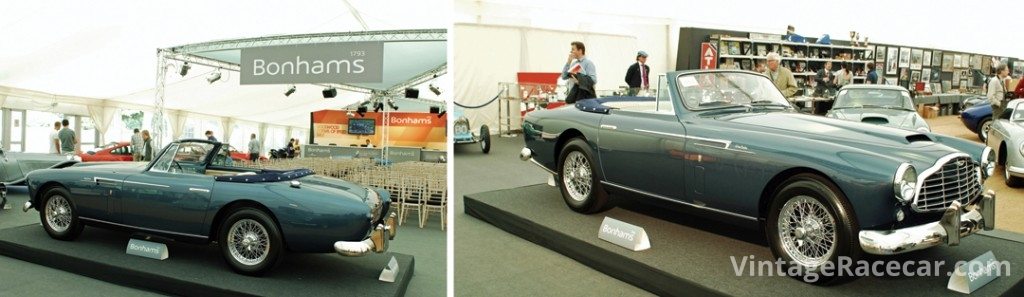

Stanley “Wacky” Arnolt was a Chicago, Illinois, businessman that after World War II, secured the Midwestern distribution rights to such British nameplates as Bentley, Bristol, MG, Morris, Riley, Rolls-Royce and Aston Martin. Desirous to be able one day to offer his own brand of automobile, Arnolt forged a relationship with Nuccio Bertone, in 1952. Impressed with Bertone’s rebodying of an MG TD, Arnolt ordered eight DB2/4 chassis and had them shipped to Bertone. There, Arnolt had Bertone clothe the chassis with striking bodies penned by either Giovanni Michelotti or Franco Scaglione. While the exact breakdown is somewhat unclear, it appears that two of the chassis (LML/504 & 506) received Michelotti-designed, drophead coupé bodies that expressed a subtly more stylized take on Aston’s existing drophead coupé penned by Feeley. However, three chassis (LML/502, 505 & 507) received much more radical, Scaglione-designed spider bodywork that featured shapely, curved fenders with pronounced ridgelines. These, combined with a pronounced center ridgeline that ran the length of the car, gave the Arnolt-commissioned spiders a very aggressive and distinctive look.

In addition to the convertibles, Bertone also built at least one (LML/765) and possibly two (LML/503, believed to have been destroyed in a fire at Arnolt’s factory) Scaglione-designed berlinettas. Replete with wraparound windscreens and subtle fenderlines that blended into tailfins, it has been suggested that this was to become the basis for a much larger run of Bertone-bodied, Arnolt-built Astons. However, the Aston factory at Feltham stopped selling rolling chassis to Arnolt, presumably due to his insistence on badging these as his own car! Aston was looking to build its own brand in the U.S., not to help create someone else’s. Interestingly, when Aston refused to sell more chassis to Arnolt, he took his Scaglione Spider design and began offering his own Arnolts, only now with Bristol power.

On September 28, 1954, a DB2/4 rolling chassis (LML/802) was sold to Prince Baudouin of Belgium and delivered to Carrozzeria Vignale, in Turin, Italy. Equipped with the larger capacity 3-liter engine, Vignale crafted a one-off, fastback berlinetta body that featured a unique wraparound rear window that hinged open, like a hatchback. The car was delivered to Prince Baudouin on March 10, 1955.

DB2/4 Mk II

In 1953, David Brown added to his automotive portfolio when he purchased the British coachbuilder Tickford. With Tickford now in-house, Brown let its designers address certain design issues with the DB2/4.

Touring

In 1956, three DB2/4 MkII chassis (AM/300/1161, 1162 & 1163) were shipped to Carrozzeria Touring, in Milan, Italy. Touring was directed to construct three, two-seat spiders. Designed by Federico Formenti and company leader Carlo Anderloni, the elegant flowing spiders foreshadowed timeless design cues that are reminiscent of the much later Ferrari 250 spiders designed by Pininfarina. Chassis AM/300/1161 was displayed at the 1956 Turin Auto Show, while Chassis 1162 was shown at the Paris Motor Show and 1163 at that year’s Earl’s Court Motor Show. One American was so taken with the Earl’s Court Show car that he bought it directly off the stand and owned the car until his death in 1989.

Ghia Supersonic

Giovanni Savonuzzi—designer of the 1953 Allemano-bodied berlinetta—developed a custom body design for an Alfa 1900-based racecar built by Virgilio Conrero, for the 1953 Mille Miglia. Savonuzzi penned a futuristic-looking design that appeared aerodynamic and incorporated many of the soon-to-be styling cues indicative of the dawning “jet age.” His design, which came to be known as the “Supersonic,” was brought to life by coachbuilders Ghia, in Torino, Italy.

The Aston Martin Supersonic was built on chassis AM300/1132 for American Grand Prix racing driver Harry Schell. Completed some time in the spring of 1956, the car was first sighted on the roads around Spa-Francorchamps, on June 3, during the weekend of that year’s Belgian Grand Prix. The Supersonic later made its official public debut, on the Ghia stand, at that October’s Turin Auto Show.

By the following year, the Supersonic made its way across the Atlantic and became the property of Robert Lee, in New York City. By 1958, the Supersonic changed hands, going first to a Mr. Caldwell and shortly thereafter, his girlfriend Paulene Whitney. Whitney drove the car for a short while—replete with a devil mascot on the hood!—until it passed into the ownership of racer and car dealer Bob Grossman, in Nyack, New York. Grossman eventually gave the Supersonic to his employee, Fred Bedford, in lieu of payment for his work, and Bedford took the car back to his home in New Hampshire. From there the car was sold to an Arnold O’Brien in the Midwest, and subsequently to Bill Mains of Detroit.

It was 1974, when the Supersonic’s current owner, Brian Joseph of Classic and Exotic Service in Michigan, spotted the now beat-down Aston in an East Detroit parking lot. Joseph chased the car’s owner until he was finally successful in acquiring the car—some 30 years later in 2004! Joseph undertook an extensive restoration of the car, which was completed in time for the 2011 Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance.

By 1955, it was clear that the DB2/4 was getting long in the tooth and in need of more power if it was going to stay competitive in the marketplace. As such, David Brown gave marching orders to his successful racing director, John Wyer, to spearhead the development of a new road-going sports car, with a larger displacement engine.

While work had already begun on a Feeley-designed DB2 successor as early as May 1955, this project was replaced by a newer approach in 1956, whereby Aston Martin enlisted the help of Carrozzeria Touring—who had so stylishly created their own take on the DB2/4 spider—to style what would become known as the DB4. Working in conjunction with Touring, Aston Chief Engineer Harold Beach designed a new platform chassis to replace the DB2’s perimeter frame. The design brief was that Touring would create a lightweight alloy body and then license Aston Martin to produce it in-house, using Touring’s patented “Superleggera” technique of welding alloy panels to a lightweight steel substructure. In the DB4’s case, the underlying framework would be a component part of Beach’s pressed steel, platform chassis. The result was a surprisingly robust chassis, clothed in an elegant body penned by Touring’s Gaetano Ponzoni, and very reminiscent of Touring’s earlier DB2/4 Spider.

In order for this larger and heavier (2800-pound) Aston sports car to remain competitive with offerings from Ferrari and Jaguar, it was decided that it, too, would need to be powered by a 3-liter engine. The task of redesigning a larger, inline-6 was given to polish émigré Tadek Marek, who joined Aston Martin from Austin in 1954. Marek took the basic W.O.Bentley/Lagonda layout of the LB6 engine and completely redesigned the bottom end to allow for seven, plain main bearings and a square bore/stroke of 92-mm. While Marek had originally intended for the block to be cast in iron, like its predecessor, capacity at the foundry that Aston used was at its limit for iron but was able to accommodate the production in alloy, resulting in a rejigging of the design for an alloy head and block!

Zagato

It is said that the idea of having Zagato create bodies for the DB4GT came when someone at Aston saw the body the Milanese carrozzeria created for the Bristol 406, in 1959. Whatever the impetus, the decision was made to commission Zagato to create a super-lightweight body for 25 examples of the DB4GT. The project was handed to Zagato’s newest designer, Ercole Spada, as his first project (!) and the result is arguably the loveliest and most coveted Aston Martin of all time.

Newport Pagnell sent Zagato DB4GT chassis that were shortened to 93-inches and featured Girling disc brakes with no servo assistance and included a higher compression (9.7:1) engine that could boot out 325-hp. Spada and Zagato, in turn, draped this potent package with a sinuous, flowing aluminum body that shaved an additional 100 pounds off of the already lightened DB4GT’s curb weight. The result was a stunning GT racer that could go from 0-60 mph in 6.1 seconds, with a top speed over 153 mph.

Bertone Jet

With the end of the DB4GT production run at hand, Aston Martin decided to use the last chassis (DB4GT/0201/L) as a flamboyant show car for the 1961 Geneva Motor Show. Harking back to their early days with the DB2, Aston selected Bertone to craft a stylish one-off body for this special show car. Bertone, in turn, entrusted the project to a young designer named Giorgetto Giugiaro. Just before Christmas, 1960, the final DB4GT chassis was sent to Turin where, oddly, Bertone crafted Giugiaro’s new “Jet” design out of steel, rather than the traditional aluminum.

Finished in light green with gray interior, the Bertone Jet featured a relatively small greenhouse, with a long, fastback-like rear window and elongated front fenders that terminated with protruding headlights. A visually striking car, many aspects of the Jet’s design can be found in later cars such as the Ferrari Lusso (front fenders/headlights) and the 500 Superfast (rear window and pillars).

While the Bertone Jet looked stunning at the 1961 Geneva Motor Show, sadly all the attention that year was sucked up by the debut of the Jaguar E-Type.

As the ’60s advanced, Aston Martin went on to introduce the DB5 and DB6, though these were essentially evolutions of the DB4 concept. While examples were built in the UK, with “Shooting Brake” or station wagon-style bodies, Aston Martin no longer looked to send its chassis abroad for bespoke special editions.

By 1965, Aston Martin was again faced with the need to come up with a larger engine to maintain the performance of its now ageing and ever-heavier offerings. The solution was to be a Marek-designed V8 engine. After having worked so successfully together on the DB4, Touring was asked to develop a design for a four-passenger version of a new car to feature the V8. However, uncharacteristically, Aston didn’t like the direction that Touring took the concept and ultimately scrapped the project late in 1965.

While the 4-seater was a non-starter, Aston also asked Touring to design a two-seat, 170 mph sports car using the existing DB6 chassis as a basis and incorporating the new V8 engine. Originally, the plan was for this new car, internally codenamed MP226, to debut at the 1967 London Motor Show, but with sales of the DB6 fading, it was decided by Aston to push the schedule up so that the new car could drum up some excitement at the September 1966 Paris Auto Show. Touring struggled to complete the project, but did manage to complete two cars in time. However, the V8 engine was not really ready yet and there were packaging issues with fitting the long, inline-6 into the Touring-bodied cars, which bore a striking resemblance to the Ferrari 275. While the cars, dubbed the DBS, were shown at the 1966 London Motor Show, Touring went out of business shortly thereafter and Aston ultimately went a very different direction with their production DBS the following year.

In the years that followed, car construction techniques and governmental regulations would make it ever more difficult for vehicles to receive custom bodies in the way they did for the preceding 60 years. As a result, the 1950s and 1960s stand out as an exceptional period of time when an enthusiast of means could order the latest Aston Martin and make it even more unique with a bespoke suit of clothing. The coachbuilt Aston era had come to an end.