1956 Ford Fairlane Victoria

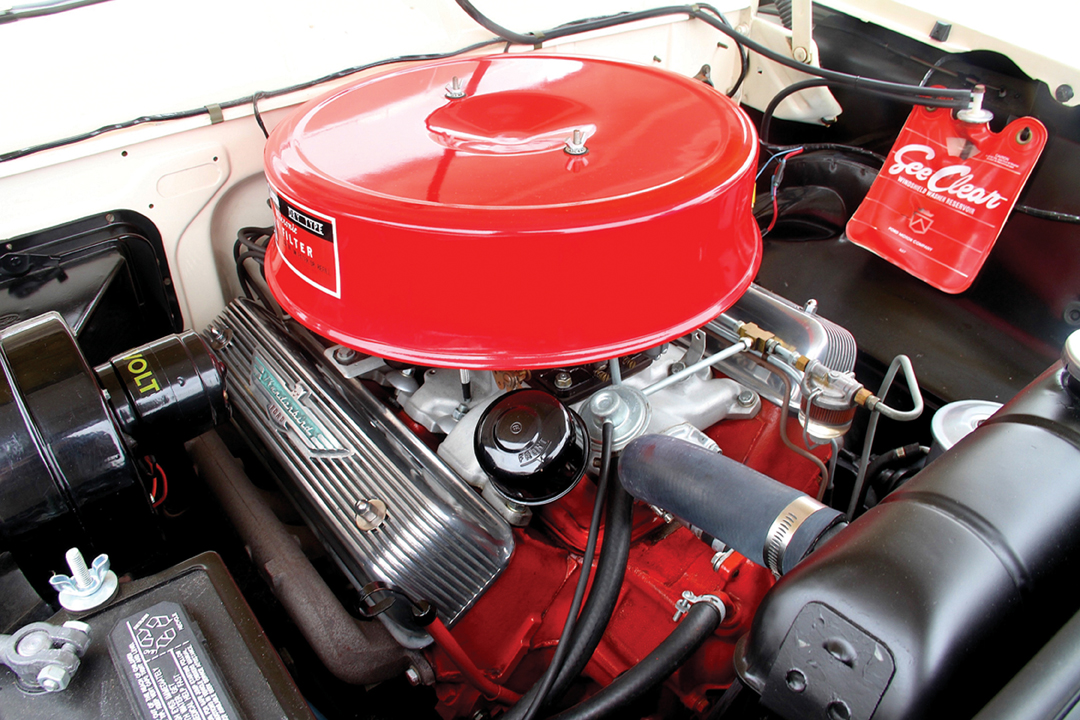

I had seen, and worked on, a lot of mid-1950s Fords over the years, so I didn’t exactly make a beeline over to see Jim Tone’s beautifully restored 1956 Fairlane Victoria at the local show and shine—that is until he opened the hood. In the engine compartment was a big 312 Y block Super Thunderbird V8, which was immaculate, but not unusual, except for the large red air filter on top with two wing nuts holding it in place. That merited closer inspection.

That was back when stock car racing actually involved stock cars. If a component wasn’t available from the factory you could not go racing with it. In fact, that is also where the term “blueprinting” came from. The racers would go through the parts bins until they found pistons, blocks, cranks and rods that were machined as precisely to the specs on the blueprint as possible. That way they would have the best possible stock engine in their racecar, rather than the usual production assembly where the pistons were fitted depending on what slid in the bore.

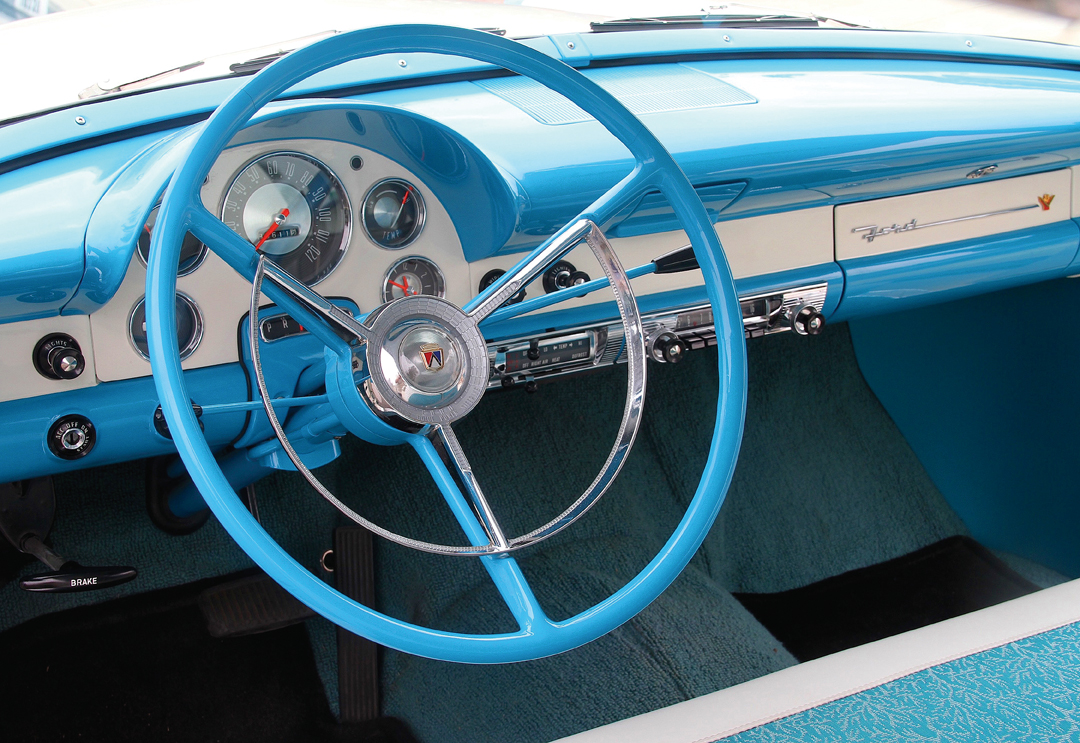

I climb in and get comfortable with the controls. The interior of Jim Tone’s 1956 Ford Fairlane Victoria is dazzling in its Peacock blue patterned-fabric and Colonial white Naugahyde interior. Remember Naugahyde? It was originally developed in Naugatuck, Connecticut, in 1936, as an imitation leather, hence the name, but by the early ’50s it had been perfected and was ubiquitous in production cars, and much less expensive and easier to care for than real leather. Of course, you had to pull your shirt away from the seat on hot days because the stuff didn’t breathe, but it was very durable.

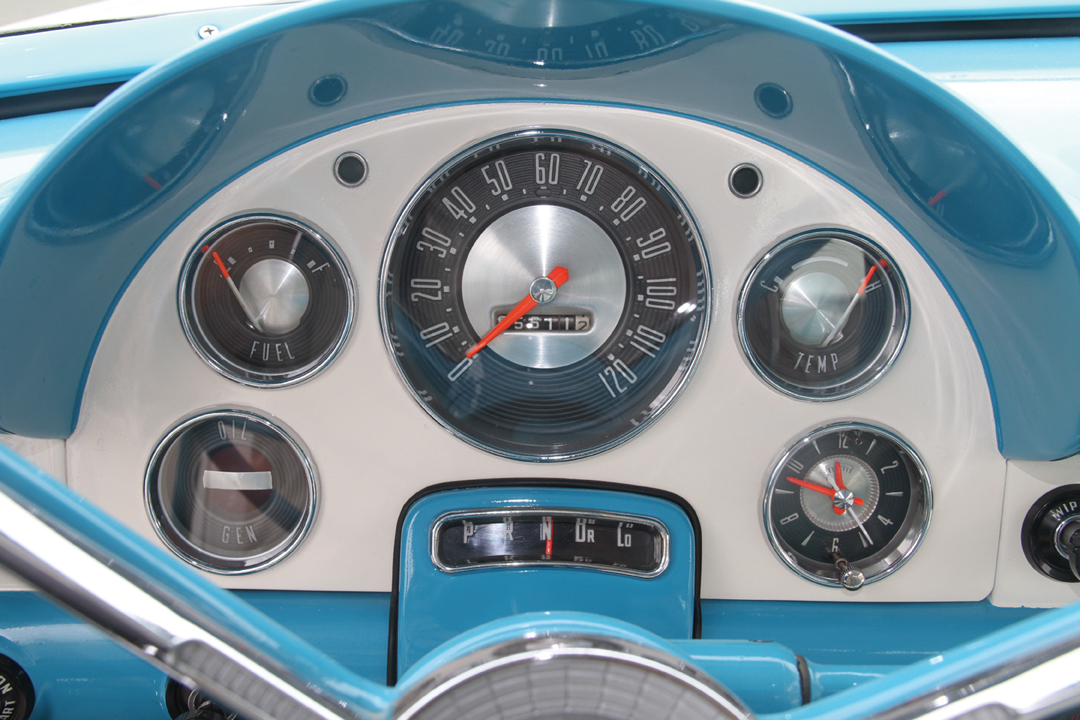

The dash for 1956 is a knock-off of the ’55 Thunderbird. It is beautifully designed, with a hooded console of big, round, easy-to-read analog gauges with everything you need close at hand. The head- and legroom is ample, and the front seat is wide enough for three people. The back seat is easily as commodious as the front, unlike modern cars in which the back seat is vestigial and would be cramped for even Danny DeVito’s little brother.

I twist the key and the starter kicks the engine over a couple of times to get fuel up to the carbs, and then the engine starts and quickly settles into a quiet mellow mutter. I pull the column-mounted gear lever into “Drive” and we are off. The engine pulls well and the Ford-O-Matic transmission shifts smoothly from second gear into high at the appropriate moment, just as the car was intended to be driven under normal circumstances. There is also an L for low—which is first gear—on the indicator too. It is intended for pulling hills, as well as for extra off-the-line acceleration when required, but not normally used, or needed while driving around town.

When the gas pedal is all in, though, with this specially equipped chariot at about 30 miles an hour, it goes like a spit watermelon seed. On straightaways it would be hard to beat with any other production vehicle of the day. This is largely a result of the fact that, in 1955, the new Chevy small-block V8s were blowing the doors off of the Fords, and that monumentally miffed Blue Oval management.

Ford actually offered a wider range of engines and packages than Chevrolet at the time, but Ford’s Y blocks were heavier due to their deep crankcases that came down around the main bearings (hence the name Y block) and their more complex valve trains. The new Chevrolet small-block had the block truncated at the parting line of the main bearing pillows, and its valves were operated by stamped steel rockers with no rocker shafts.

That drubbing, at the track in 1955, encouraged Ford to come up with their B6A-9000-B Interceptor performance package, which originally consisted of two Holley “teapot” four barrels, an aluminum manifold, the above mentioned Purolator paper air filter, plus special ECZ-C cylinder heads, stouter valve lifters and springs, a hot cam, and a recalibrated distributor. All of this brought mileage down to about ten miles to the gallon, but almost nobody cared.

Ford’s early Y blocks were good dependable engines, except for one problem. They did not always get enough oil to the rocker arm assemblies because the oil first went to the crankshaft bearings, then to the cam bearings, and finally to the rocker shafts. The problem was further exacerbated by a design problem in which the passage from the center cam bearing to the cylinder head was offset by an inch and a bit too small.

The oils of the period were non-detergent or low detergent and high in sludge production, so if you didn’t change your oil at the recommended 1,000-mile intervals, these galleries plugged up, and though the engine’s bottom end got more oil as a result, the rocker shafts and assemblies galled and burned due to a lack of it.

As we cruise around Tone’s, neighborhood people wave and get out their cell phones and take pictures. This is a car from America’s golden age of design and style. Of course, it doesn’t measure up to modern cars in terms of electronic falderal, but in sheer driving pleasure and adventure, there is nothing like it today. The pillarless hardtop and bright interior make you feel out and in it instead of enclosed, and the mellow rumble of the factory dual exhaust exiting through the rear bumpers gives you a feeling of power.

Because of the increases in power and speed and the high-speed highway programs of the time, fatal crashes became all too common, but Jim Tone’s Vickie is a uniquely safe car in which to be cruising. That’s because Ford put a lot of emphasis on safety in 1956, though in the end it did not increase sales a great deal, but it very likely saved lives.

Sadly, safety was never a big selling point for the auto industry. Nevertheless, Ford offered their Lifeguard double-grip door latches and a deep center steering wheel for 1956 and a padded dash and visors were available for a few more dollars. Also, Ford offered safety belts for the first time beginning in 1955 as an option. All of these innovations became standard later.

Much of the styling of the ’50s took its cues from jet aircraft, including swept back fins, hooded headlights that looked like air intakes, and taillights that appeared to be jet engines with the afterburners kicking in. There is no doubt that, though the innovations of the jet age were done for aerodynamic reasons on aircraft, they had an undeniable iconic beauty to them which was as much as anything else, the result of science homing in on the essential truths of physics. Somehow using those innovations as symbols, albeit with a basic shoebox body, worked for Ford.

In 1956, there was little inflation, little unemployment, and gasoline was 22 cents a gallon, so people wanted more out of their Fords than what had been offered during the depression years, and they got it. Also, by the mid-’50s the railroads had lost ground as long-distance transportation due to the development of inexpensive, fast, comfortable cars, the suburbanizing of the population and the new highway system fostered by President Eisenhower.

We have the atomic bomb to thank for that. The cold war thinking was that spreading out the population would make it more difficult to annihilate, and the highway system would make it more efficient to move troops and supplies in the event of an invasion.

My plan, as a lad back then, was to heroically throw myself on a girl named Rita Garcia, thus shielding her from harm and earning her everlasting love.

I also wanted to be a jet fighter pilot in the worst way, and loved the cool new automotive styling cues of the Vickie that would at least let me do that vicariously.

At the same time, owning such a car might have also impressed Miss Garcia. It was not to be though. The Russians may have had a tyrannical, maladaptive economic system, but they weren’t crazy, and besides, all I could afford in my youth was a ten-year-old Chevrolet anyway.

Aside from the possibility of nuclear obliteration, things seemed very positive in the ’50s. We were aware of the great strides in medicine, such as finding the polio vaccine, the new electric appliances that made life easier, and 3D Cinemascope movies that made you part of the story. It seemed that science and progress would solve all of our problems as long as no one lost it and pushed the button.

Jim Tone lived through all that too, and during those years his mother drove a 1955 Sunliner convertible that his father bought for her. His father also bought a 1956 Victoria a year later that Jim would take on dates, and for which he developed a great affection.

Although his racing hobby was largely consumed with GMC six-cylinder truck engines, he always retained a soft spot for the mid-’50s Vickies.

And then, in 2011, Tone’s wife Jean, after years of listening to his reminiscences, told him she had always admired the mid-’50s Vickies too, and why didn’t he buy one? They started looking, and Jim soon discovered one at a dealership in Arizona that had undergone a 12-year restoration. He needed to fix a few minor items, such as the headlight switch, radio and power steering, and he had to go through the cooling system, but the rest of the car was show quality.

Then Jim acquired one of the very rare big red Purolator air filters, and decided to see if he could gather the rest of the B6A-9000-B racing kit. He found all the important items, but says: “Due to problems finding parts and information I took a few liberties with lines, linkage and brackets; but overall I am happy with the result. A 1956 Victoria with dual quads is not something you see every day.” And that is an understatement.