This man was a motor racing whirlwind, journalist, author of seven motor sport books, vintage car fan, ran driving courses for the British police and was the founder, president or vice-president of some of the UK’s most prominent motoring and racing organizations. And he kept up that pace until he died at the age of 94 in 1981.

The only time I ever met Sammy Davis was in 1978, when he was a friend’s lunch guest at a London restaurant. We had all finished eating, so I was invited to join them both for coffee. And what an experience that was! Even at 92-years old, Sammy Davis was a motor racing dynamo, bubbling over with enthusiastic memories and still drove himself around in a frog-eyed Austin-Healey Sprite.

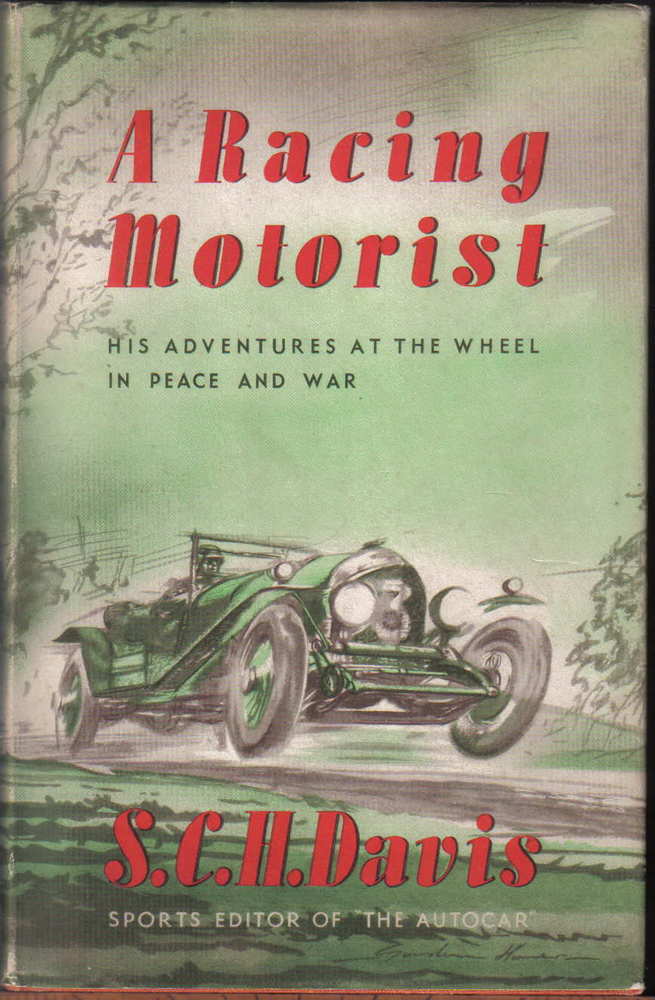

Born in central London on January 9, 1887, Sydney Charles Houghton Davis, aka Sammy, went to the Westminster School and, later, the University College, London. After that, Davis became a Daimler apprentice draughtsman and was a junior member of the team that designed the company’s car for the 1907 Kaiserpreis, a motor race in honor of Kaiser Wilhelm II, the ruler of Germany, won by Vincenzo Lancia in a FIAT, while the Daimler retired. Sammy also fancied his chances in the motoring press, so in 1910, he first became a technical illustrator for the new publication Automobile Engineer and later a journalist sub-editor in 1912. After the First World War, Davis joined the British motoring magazine Autocar, first as its motor sport editor and later he became the author of his famous “Casque” (French for helmet) column for the publication.

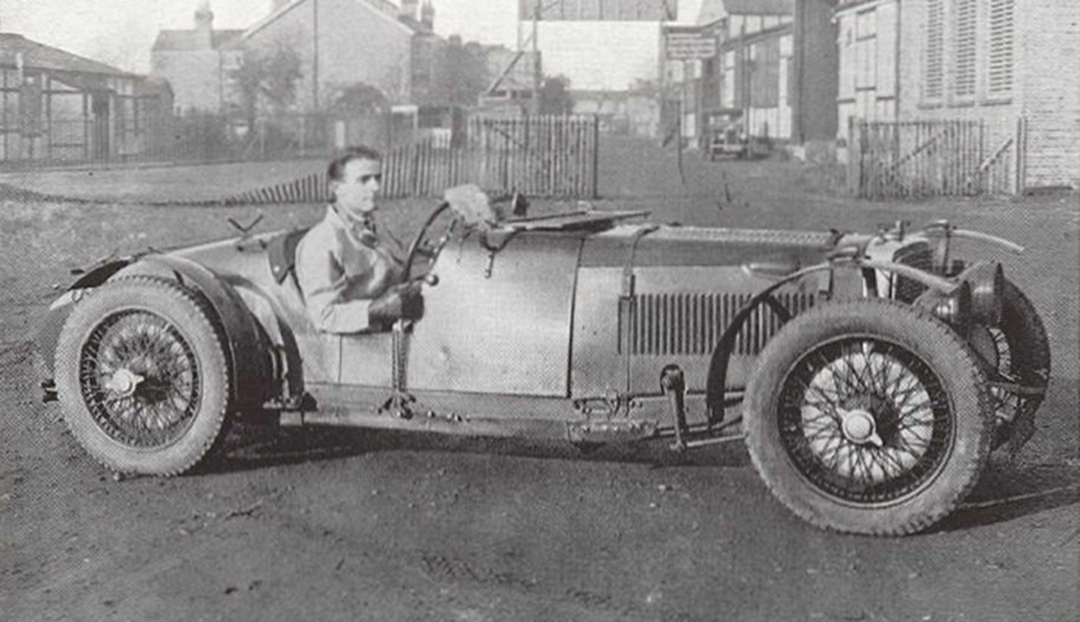

As a racer, Sammy first drove for businessman and 1902 Gordon Bennett Cup winner Selwyn Edge’s S.F. Edge Brooklands AC racing team in 1921. A year later he moved to Aston Martin, for whom he helped break no fewer than 32 world and class records at the mythical circuit in Weybridge, Surrey, England.

One of the original Bentley Boys, Davis helped brothers W.O. and H.M Bentley to establish their company, in 1919, and was key in persuading a skeptical W.O. to allow one of his cars to compete in the first ever 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1923. Bentleys ended up winning the prestigious endurance classic six times, in 1927 with Sammy Davis and Dr. Benjy Benjafield driving a Bentley 3-liter Sport. Sammy had already come second with Jean Chassagne in the 1925 race campaigning a 3-liter Bentley; crashed at the Sarthe in 1926 when he and his Bentley 3-liter Speed were trying to snatch the lead 20 minutes before the race’s end; came ninth in an Alvis in 1928; a stone smashed his goggles in the 1929 Le Mans so he had to retire from the race; and in 1933 he came seventh in a 1.5-liter Aston Martin.

There is quite a tail behind Davis’s victory in the 1927 24 Hours of Le Mans. He and Benjy Benjafield won driving their badly crumpled 3-liter Bentley, the survivor of a six car pile-up at the White House at 9.30 at night.

Frank Clement’s Bentley 4.5-liter was in the lead, with Jacques Canterelle in a Théophile Schneider trying hard to catch him, but Jacques got it all wrong at the White House series of corners. Cantarelle went into Maison Blanche too fast, cannoned into a ditch, bounced back onto the track again and ended up almost blocking the circuit. Next on the scene was Leslie Callingham in a 4.5-liter Bentley and, seeing his path was blocked, purposely rolled his car and was thrown out into the center of the track for his trouble. Then along came Robert Poirier in a second Théophile Schneider, but he had no time to take evasive action and charged at full speed into a stricken Bentley and Cantarelle’s car. Then another two cars smashed into the wreckage, after which Sammy Davis charged around the bend in his works Bentley and, seeing the five mangled cars, put his 3-liter into a slide to hit the wreckage sideways.

Although Sammy’s car was badly smashed about, he was still able to re-start it and limp back to the pits. Only the drivers were allowed to fix their damaged cars in those days, so Davis and Benjy did their best to put the Bentley back together again, which included fixing the front wing back on the car with string! Other damage included a broken front headlight, a bent front wheel, axle and chassis, but Sammy decided to press on regardless, although well down the field. Benjafield took over six laps later and set off after the new leader Jean Chassangne in a 3-liter Ariès. As well as tying the front wing back on with string, they rigged up a powerful torch that was anchored to the other side of his windscreen frame as a meagre substitute for the smashed headlight. The lead car had ignition trouble, which took it into the pits several times and was eventually retired. Now leading, the strung up Davis-Benjafield Bentley slowed noticeably, but still won the race having covered just 1,472 miles against the period’s record of 1,585 miles.

Two years later, it was back to Brooklands for the Le Mans winner, where Sammy in his Bentley 4.4-liter came second to Alfa Romeo star Giulio Ramponi’s Alfa 6C 1750 TF in the exhausting Brooklands Double Twelve – a two, 12-hour heat event – and won his class in the car. A year later, Davis partnered the Earl of March in an Austin Seven to become outright winners of the circuit’s British Racing Drivers’ Club 500-mile event by averaging 83.1 mph. In 1929, Sammy also set five class H records at Brooklands in the Austin, including a flying kilometer of 143.36 kph (89.08 mph). All of which earned him the prestigious BRDC gold star.

In 1930, Davis came second in the Brooklands Double Twelve again driving a Bentley 4.4-liter.

Writing his weekly columns under the pen name “Casque” for Autocar and with a distinguished racing career on the go, Sammy still managed to become a founding member of the Veteran Car Club of Great Britain in 1930, and 30 years later he regularly drove his 1897 Bolleé tri-car until he sold it to the Indianapolis Speedway Museum. He was elected vice-president of the Aston Martin Owners’ Club in 1935 and was the designer of the car maker’s winged badge.

And when the Second World War ended, Davis was a key player in getting Britain’s motor sport back on its feet as vice-president of the country’s Vintage Sports Car Club and president of the Half Litre Car Club, as well as a committee member of the BRDC. He was later elected to the Competitions Committee of the Royal Automobile Club, the motor sport sanctioning body in the United Kingdom.

While all this was going on, he still found time to go to races and write and paint excerpts from them, as he was also a keen artist – and was an enthusiastic competitor in the London to Brighton Veteran Car Run in his Leon Bolleé.

This remarkably active man—and, in his day, star racing driver—died in 1981, in a fire at his Guildford home that took place on his 94th birthday.

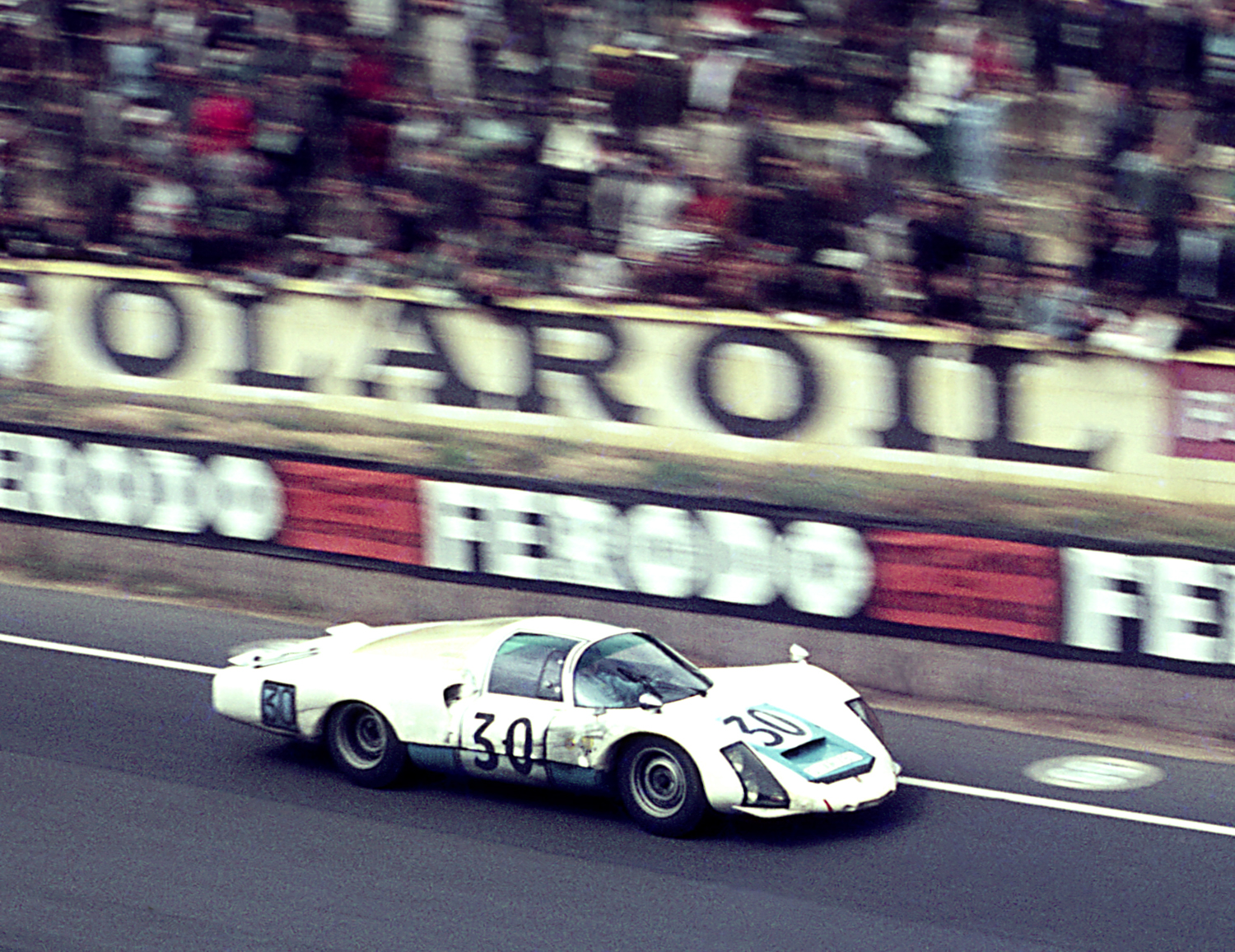

His son Colin also raced, his greatest result victory in the 1964 Targa Florio with Antonio Pucci in a Porsche 904 GTS and came fourth with Jo Siffert driving a Porsche 906/6 LH in the 1966 24 Hours of Le Mans. Colin died in 2012 after a long illness.