Since the dawn of motor racing there have been those who continually ask the question, “Who is the best driver?” Some give very qualified opinions, others are dogmatic that the man they have supported over many years is the best and then there are those scholars and mathematicians who believe a complicated algorithm, taking in all the various disciplines of the sport and the cars driven, will ultimately yield a definitive answer. Interestingly, the sport itself thought of a much easier answer, put these drivers on a track and let them fight it out between themselves.

In the UK the “Race of Champions” was an F1 race held at Brands Hatch where teams would go head to head, not for a Grand Prix crown, but to find the champion driver. The first of these races was held in 1965 with Mike Spence taking the honors (over two heats) in a Lotus 33, beating teammate Jimmy Clark, after Clark’s car failed in Heat Two. From 1965 to 1983, there were 14 editions of this race—the last being won by Keke Rosberg in a Williams. However, while the first running included the top drivers of the day, by 1983, it had become somewhat diluted and meaningless. Ultimately, it didn’t prove a great deal and simply became a test session prior to the onslaught of the European rounds of the F1 World Championship series of races.

Photo: Pete Austin

IROC I – Porsche RSR

In North America, there was a more conclusive idea for finding the best driver of the day. The drivers, who had won major races, or major championships at major tracks throughout the world, were invited and selected to participate in the “International Race of Champions” (IROC). These drivers, from many disciplines of the sport, raced in identical cars and, over a series of races, a true winner and champion would be found. Created and developed in 1972 by Roger Penske, Les Richter and Michael Phelps, the first three of the four-race series took place on the weekend of October 27-28, 1973, at the Riverside International Raceway, with the final race being held at the Daytona International Speedway. The drivers, Mark Donohue, Peter Revson, Bobby Unser, David Pearson, George Follmer, A.J. Foyt, Emerson Fittipaldi, Denis Hulme, Richard Petty, Gordon Johncock, Bobby Allison and Roger McCluskey were great international drivers of the day representing Can-Am, Formula One, Indycars, NASCAR and the SCCA series of races. As the entire series was run on road courses, the car for the inaugural event was the Porsche 911 Carrera RSR. In total, 15 of the cars were prepared by Penske Racing (12 racecars and three spares), to identical specification, and although RSR in name they were actually upgraded RS cars with 3-liter Carrera RSR engines fitted. Modifications were made to the bodywork to include a revised rear wing and extended wheel arches to accommodate Fuchs wheels. These identical cars were allocated to their drivers by a blind drawing before each race; the only difference between them was the color and the race number. Although practice was allowed, there was no qualifying, once again there was a draw for starting positions for the first race, the second race start was in finishing order of race one, but with the winner starting in last place and the loser starting from pole. Race Three started in an inverted points order of the first two races—the driver with the least points being on pole and the driver with the most in last place. Race four started in points order—the driver with the most points on pole. Winning wasn’t confined to the first man crossing the line, but the driver who earned the most points/prize money over the series of racing. All 12 drivers took part in the first three rounds and the top nine prize money winners fought it out in the last round. Mark Donohue took the spoils by winning the first IROC series, amassing some $54,000, 2nd place was Peter Revson with $21,200 and 3rd Bobby Unser with $19,100. However, reports suggest it was George Follmer who wowed the crowds with a brilliant driving display starting from 12th and finishing 4th in Race 1, in Race 2 starting 9th he finished 1st, in Race 3 he again started 12th and finished 5th and, in the final race, the duel between Donohue and Follmer only ended when Follmer spun leaving Donohue to head for victory.

Despite the theoretical success of this pioneering series, many drivers complained about the curious handling of the Porsche with Hulme, Revson, Fittipaldi and Bobby Unser reportedly referring to the car as a “heap of trash,” adding that they felt Donohue had an “unfair advantage” as he was a regular Penske Porsche driver. Like many new ideas there were those spectators who thought the drivers were just having a jolly time and not taking the racing too seriously, but once the helmets went on and they were buckled and belted in their cars, it was clear they meant business. On the driver front, A.J. Foyt was a particular skeptic, originally saying he didn’t like the idea and wanted no part of it, but then reconsidered saying, “If there’s going to be a race of champions, no way am I not going to be in it.” On the whole, the concept of the series was widely approved, and this first running would lay the foundation for an annual series for the next six years and beyond in various guises. It was, however, agreed the Porsches needed replacing. A new chassis was sought for the following season.

Chevrolet Camaro

General Motors produced the Camaro, a two-door coupé, or convertible 2+2 seater, originally named Cheetah, under its Chevrolet banner back in 1967. Most performance cars of the day were named after animals; Mercury Cougar, Shelby Cobra, Corvette Stingray, Pontiac Firebird, et al. So, at the launch, when Chevrolet product managers were asked, “What animal is a Camaro?” they were simply told, “a small animal that eats Mustangs.” Yes, the Camaro was a direct competitor, in the pony and muscle car stakes, to Ford’s popular and very successful Mustang. The Regular Production Option (RPO) of the Camaro was the Z/28—possibly one of the most famous production codes ever, and synonymous with outstanding high performance. The cars were initially produced in the seven-year period from 1967 through to 1974. After a hiatus of just two years, in 1977 the Z/28 returned. The big bumpers were still a prominent feature, but some new styling included a wraparound rear window and new power by a 350-cu.in. V8 engine giving around 185 hp. Handling characteristics were upgraded by using stiffer spring rates, thicker stabilizer bars and firmer shock absorbers. Despite only being launched in the spring of 1977, record Camaro sales outsold Ford’s Mustang by year end.

In racing terms, the Z/28 was accepted by the SCCA to race in the Trans-Am series, and worked effectively well with Roger Penske’s Penske Racing Organization winning the 1968 and 1969 titles with Mark Donohue at the wheel. Eventually, the Chevrolet Camaro Z/28 was identified as the replacement to the Porsche Carrera RSR as a more suitable racer. So, from IROC II onward it became the car of choice for the subsequent years of competition. Of course, Penske’s relationship with Chevrolet must have been a major sway. Again assigned to ready 15 identical production-based cars, Penske Racing hurriedly prepared the first generation of IROC Camaros in just nine weeks. They were powered by the Chevy small block V8 engine and had 4-speed transmissions and were very similar to the cars raced in SCCA events. Donohue, the reigning IROC champion, had now retired from racing, although history shows he was lured back to drive for Penske’s F1 team and tragically killed in practice for the Austrian GP. However, at the time of his brief sabbatical, he remained with Penske in a role to assist with the technical direction and development of the Camaro, ensuring the car was fit for the purpose, stating, “The object wasn’t to build the world’s greatest racecar. It was to build 15 cars with equal potential.”

There was a rule change for IROC II in as much as the races would now be run on two ovals and two road courses, alleviating any suggestion that the series benefited road race drivers over oval racers. The 1974-’75 season found Bobby Unser winning the series. In 1975-’76 (IROC III) and 1976-’77 (IROC IV), A.J. Foyt was the overall winner despite not having won a single race, though he stacked up a winning prize tally with a series of good finishes. Although the production-based Trans-Am Camaro had basically fulfilled the role required by delivering great racing and performance, issues with rebuilding and setup after the inevitable crashes became a problem. The fervent driving styles of competitors, breaking and bending the cars, had dramatic effect on the various crewmen, many of whom had to pull all-nighters to ready the cars for the following day’s racing—despite having three reserve cars. It was also found that production-based cars were not suited to racing on ovals, so a solution had to be found. Additionally, there was still a desire to ensure it was driver, rather than car, performance that produced a true champion. Minimizing mechanical variables was the order of the day for the next generation of Camaros to be readied for IROC’s Series V. Enter Banjo Matthews.

“Banjo” Matthews

By the time Roger Penske went looking for a new car for IROC V, Edwin “Banjo” Matthews had already developed a professional standing for building successful NASCAR racers. Prior to full-time building cars, Matthews was a very proficient racer from Akron, Ohio, winning many, many races behind the wheel of his modified cars on both dirt and asphalt tracks. By this time, he moved to Asheville, North Carolina, where after retiring from racing he spent time preparing cars for Ford and opened his own workshop. His following and reputation soon grew for producing some great cars, being dubbed a maestro mechanic and the “Henry Ford of racecars.” A sign displayed in his race shop exhibited his basic principal of preparing racecars that is still true today, “Banjo’s, where money buys you speed—how fast do you want to go?!” Modestly, Matthews always said, “It’s not the basic construction of a car that wins races. It’s the team effort after the car leaves our facility that separates the winners and losers. We strive to build our cars as good for one customer as we do for another. The credit for the performance goes to the people who operate them.” Having already prepared Winston Cup championship-winning cars in 1975 and 1976, Matthews became an understandable candidate and was commissioned to build the next IROC cars—with an emphasis on indestructability.

While the Camaro was still the flavor of the series, Matthews gave these new cars the stock car treatment by building an all-new steel frame, square sectioned rails with round tube section for auxiliary parts to hang the heavy-duty drive train and suspension from. Very briefly, heavy round section stock also formed the roll-cage to give maximum protection to the driver. To save weight, body panels were predominantly replaced with fiberglass, although original GM panels were used on the roof and trunk sections. Power came from the thirsty 4.5 mpg Traco 350 Chevrolet engine producing 450 bhp at 6500 rpm, transmitted through a T-10 four-speed gearbox. The steering was changed between oval and road course tracks, utilizing a slower Ford box for the ovals and the quicker Chevrolet for the road courses. This change ensured high performance levels and suitability to the differing characteristics of circuit racing. Holman-Moody products replaced many of the original parts, including front hubs and parts for the live axle, but the Hurst-Airheart 12-inch diameter, dual-caliper, four-wheel ventilated disc brakes were as on standard Z/28s. Indeed, although from the outside the car resembled a Z/28-Camaro this car was a “wolf in sheep’s clothing” in reality, a racing silhouette of the road car. Test driver George Follmer was asked to drive all the cars to ensure parity. His findings were summed up at the conclusion of the test, “I can’t say that one car is going to favor Foyt because he oversteers more than one for Johncock, who prefers a car that pushes. If a car suits a little guy a little better, well that’s the way they all are. Each driver will have to make his advantages where he finds them.” The real acid test would be performance on the day.

IROC V

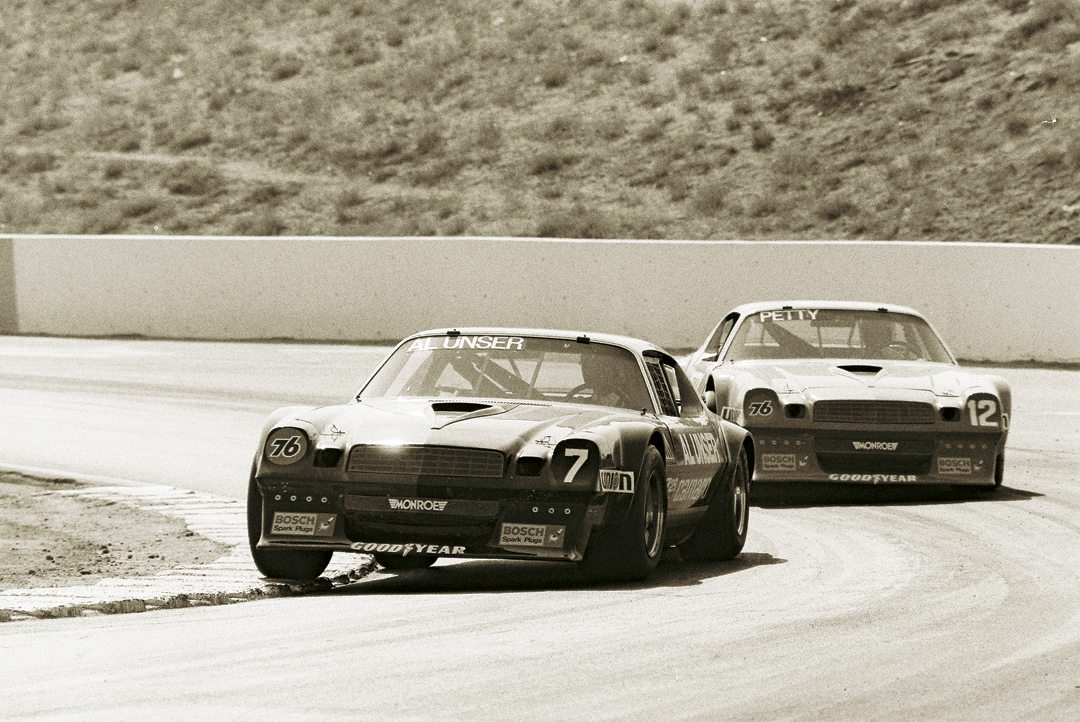

Invited drivers for IROC V were, Al Unser, Mario Andretti, Darrell Waltrip, Cale Yarborough, Richard Petty, Gordon Johncock, Gunnar Nilsson (due to ill health Nilsson was replaced by Benny Parsons in the finals), Jacky Ickx, Johnny Rutherford, Tom Sneva and Al Holbert. The series was reported as being one of the most physical up to that point, giving credence to the organizer’s decision to use Banjo Matthews-designed cars. Round 1 was held on September 17, at Michigan International Speedway, a two-mile banked oval, theoretically suiting the NASCAR boys. Rain had delayed the start, but once under way Al Holbert was the first to test the strength of the new chassis, crashing on lap one and sliding on the top of his Camaro for the entire length of the back straight! Sneva and Ickx were also involved in this incident and all three retired from the race. Al Unser narrowly took the flag, followed by Yarborough, Waltrip and Petty. One month late, on October 15, 1977, the IROC circus moved to Riverside International Raceway in California, and Al Unser once again proved he was the “cream of the crop” with a flag-to-flag victory. Petty, Johncock and Andretti were the next to finish, but the series was Unser’s to lose having an almost unassailable lead with maximum prize money. Again at Riverside, Race 3 was held the following day—inverting the finishing order to determine the grid meant Big Al needed to pull something out of the bag to gain victory in this 30-lap race. Indeed, a gritty performance saw him rise to 3rd place and a podium finish, but Yarborough took the spoils followed by Andretti, with Darrell Waltrip finishing 4th.

Four months later, on February 17, 1978, the final reckoning would produce the final standings in the series, although Unser was already the 1977-’78 champion. The top nine drivers from the previous races made their way to the 2.5-mile Daytona banked tri-oval for the 40-lap, 100-mile finale. On a sad note, Gunnar Nilsson had qualified for this final reckoning, but due to ill-health (that would ultimately claim his life in October 1978) withdrew and was replaced by Benny Parsons. The race would again test the resolve and strength of the new cars. Just after the midway point of the race a crash involving two-thirds of the field red-flagged proceedings. The tangle included Petty—who had to be taken to the hospital for treatment after being knocked unconscious—Unser, Andretti, Rutherford, Johncock, Waltrip and Parsons. Unser’s car was damaged beyond repair, but Mario Andretti would go on to win the restarted race, with Waltrip, Johncock and Yarborough finishing 2nd through 4th respectively. The real success of the series though, was the car, a Banjo Matthews creation that more than stood up to the rigors of IROC racing and was used for the next three iterations of the IROC series.

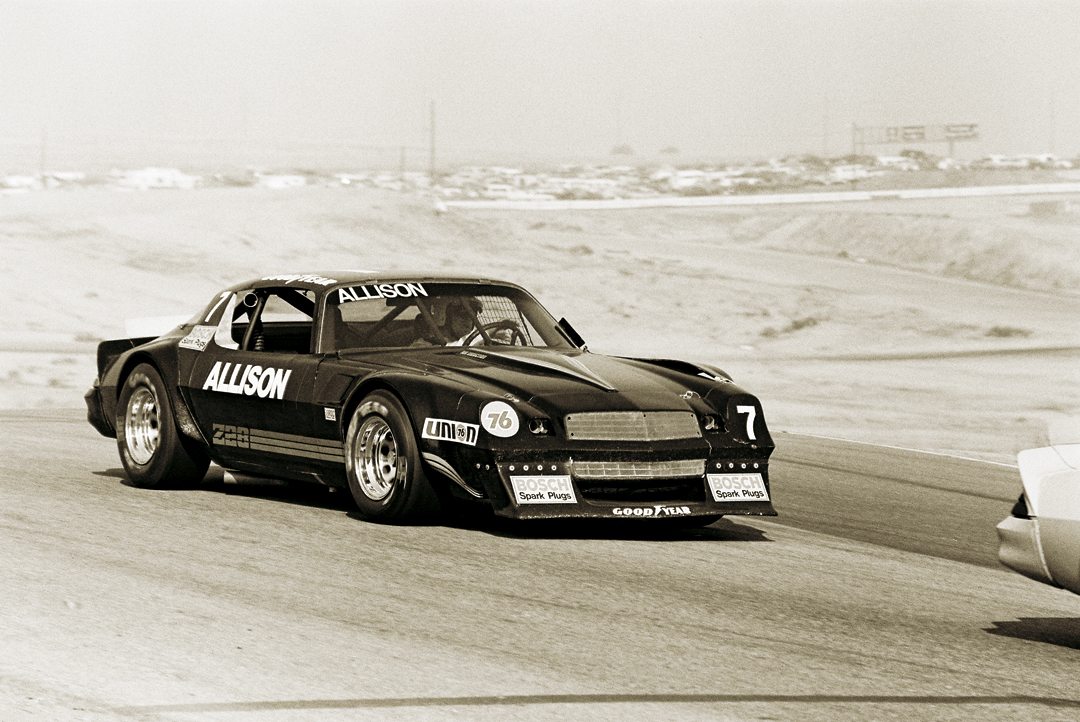

IROC Camaro chassis 7

Our profile car is chassis 7, the black car, that saw battle not only in the 1977-’78 IROC V series in the hands of Mario Andretti, Al Unser and Jacky Ickx, but it was then raced through to the IROC VII series final in 1980, having also been driven by David Pearson, Gordon Johncock, Mario Andretti, Neil Bonnett, Cale Yarborough, Rick Mears and Bobby Allison. From 13 races it took seven podium places including two victories—Al Unser at Riverside for IROC V and Neil Bonnett at Atlanta during IROC VI.

The car is a true Banjo Matthews creation, second-generation Camaro. It has an original floor pan, A-post, B-post, roof and trunk sections that are all standard, with the modified subframe where the engine is moved forward. Effectively, the front suspension is all NASCAR-style in construction and design. All the front-end body shell is fiberglass. Regrettably, the original engine was removed post-IROC racing period and replaced with a 5.7-liter Dodge Dart engine with alloy heads and all-steel bottom end and dry sump. Over the years, the cubic capacity has been increased, for one reason or another, so now we’re at 5.8, or 5.9 liters, yielding around 500 hp. While the car is very robust, there were certain repairs that have been necessary over the years to bring the car up to its present finish, but all of these have been done in a sympathetic way to retain the true appearance and specification of the car. The car, now owned by John Truslove for the past nine years, has been restored and prepared by Mike Luck’s Classic World Racing facility in Redditch, Worcestershire, England. It has been seen recently at Goodwood’s Festival of Speed and now is taking to the track for its first racing since the IROC series of nearly 40 years ago.

Driving the Black 7

It is normal practice for us to take the car on a test drive around a particular circuit and report back our findings. Yet, in this case, it would be only right and proper to give the Z/28 a run in true IROC style and conditions using both a road course and an oval. The chosen venues, situated in Northamptonshire, were the National Circuit at Silverstone (1.6 miles) and the UK’s only banked American-style oval at Rockingham Motor Speedway (1.48 miles).

Silverstone National Circuit

Photo: Jutta Fausel-Ward

I have to say, on a rather bleak, damp and cold day, apart from the odd spell and glimmer of light from the sun, the Camaro Z/28 truly warmed the soul. Even silent and stationary, the black, menacing, but purposeful body shape and style gives vibes of power, performance and ultimate racing pedigree. If proof were needed, the large ice white decals “AL UNSER” underlined by the word “Camaro” emblazoned on the side panels give notice of the car’s positive racing history. What more will the Camaro give when sparked into life? Inside, the roll cage overwhelms the sparse cabin and the black metal dash supports gauges of function rather than elegance. Having gone through the relevant and conventional sequence of readiness, the car is now fully prepared and readied for our test. On ignition the noise emitted is a cacophony that fills the whole of the pit lane, adjacent garages and immediately turns heads. Yes, it’s not the burst from a Chevy block, but I’m assured the grunt and muscle delivered from the Dart unit are on a par with the original.

Access to “the office” is gained by climbing through the left-hand window aperture. Once in, although the racing seat is basic, it feels more supportive and workmanlike than first impressions suggest. Strapped in, the vibrations are felt not only through the seat of the pants, but the steering wheel too, it’s similar to sitting astride an untamed horse, every sinew of your body is awakened by the power of this beast. From a racing point of view, particularly here at Silverstone, I appreciate I’m sitting on the “wrong side” of the car, with minimal if any chance of viewing the almost all right-hand apexes of the corners—although I have to say that my vista is far greater than I’d imagined. Apart from a minor tweak to the final drive ratio (fairly low at 3.7) to assist performance on the Silverstone National Circuit layout, the Camaro is largely set to how it would have been in period for a road circuit. After two or three laps of the drying track we’re now getting used to the car and ready to put it through its paces. Up to now the Camaro feels very compliant and soft compared to most contemporary cars.

The wide track and long wheelbase are instrumental to this impression, and as a result the car doesn’t feel the beast I first thought it was. There’s an air of confidence in that it can be pushed without any dramatic, or unsavory, effects. The braking is very good, given they are the original calipers—albeit fully restored. Any preconceived issues with apexes have been dissolved on these initial laps as the car actually responds well and steers where pointed. So, we’re exiting Woodcote in fourth gear with foot down, taking advantage of the pit straight and building to around 130 mph prior to approaching Copse. The car is very torquey and it’s a question of using just third and fourth gear—even through the tightest of corners. Nearing 130 mph as we approach the first marker board, we’re off the gas and gently nudging the brakes to scrub off speed, gently changing down to third gear ready to accelerate again through to Becketts. Becketts is tight, but we’re told that second may cause a few problems, so use third and the torque of the engine to negotiate the right-hander. Club Straight, now known as Wellington Straight, gives an opportunity to touch 150 mph, but once under the bridge it’s time to consider the tight left, only the second time in the lap where the apex is clearly visible. This time, it’s prudent to slow the car down and use second gear to negotiate and provide that extra acceleration needed on the short straight between the exit of Brooklands, through to the entry of the 180 Luffield Corner. Building speed as we turn and changing back up to third and then fourth, we soon exit Luffield and drive through Woodcote hugging the pit-walled apex, then moving to the left as we drive through to the cross the Start/Finish line. It’s a satisfying feeling hurling this big brute of a car round the relatively small club circuit, knowing that you’ve possibly got the best performance you can, given the damp track and cold ambient conditions. We’ll now head some 40 miles northeast, but still in Northamptonshire, taking the car to Rockingham Motor Speedway, knowing the Camaro will feel more at home there and trusting the British climate improves.

Rockingham Motor Speedway

We’re on the outskirts of the former steel town of Corby, indeed virtually on the site of the Stewarts & Lloyds original works that produced tons of steel tubing, until the industry was nationalized and became part of British Steel in the mid-1970s. A few short years later and 5,000 jobs were lost and the former buildings stood empty, lifeless and derelict until the mid-1990s when regeneration brought the construction of a 350MW power station that now sign posts the entrance of the Rockingham Motor Speedway, opened just a handful of years later. Built to full U.S. oval track specifications the 1.48-mile long, four-turn track is 60 feet wide with a 3.5 to 7.9-degree maximum banking. Full of promise the new facility opened in 2001 with the CART Championship as its headline event. Gil de Ferran in a Penske Reynard-Honda won this first “Rockingham 500” and the second CART race, the “Sure for Men Rockingham 500,” found Dario Franchitti in a Team KOOL Green Lola-Honda taking the win. The outright lap record was set in that first event by Tony Kanaan in his Reynard-Honda lapping at some 24.719 seconds, 215.397 mph. Of course, 9/11 intervened and the U.S. series hasn’t visited since. For a time, the future of Rockingham Motor Speedway was in some doubt, but while the Indycars no longer visit the UK, thanks to the addition of a road circuit inside the oval, there is still life at Rockingham.

As the IROC Camaro Z/28 was being unloaded from the transporter, the weather once again played a hand. Our track time was in some doubt for most of the morning with heavy precipitation and rain clouds rolling over the circuit. By chance, the wind took hold, the clouds dispersed and although the ambient temperature was still very low, the track started to dry allowing us time to run the car. Yet again, the Camaro, every inch a racecar, looked resplendent in its black IROC period livery, hopefully the 7 displayed would be a sign of good luck that the weather would hold, giving us enough track time to evaluate the car. Once prepped and ready to go it was time to alight through the driver window and put the car through its paces. With the lone unsilenced engine echoing through the deserted grandstands, a handful of people stopped in their tracks and stared as we made our way down the pit lane.

The car had behaved remarkably well in similar conditions to those at Silverstone. In hindsight, it made this test more valid and on a par with the previous, so a true validation could be made. However, it was important to remember that the car now has a “symmetrical” geometry suitable for road circuits rather than the typical “asymmetrical” geometry designed specifically for IROC’s left-turn ovals. Damp or otherwise, this fundamental setup would ultimately govern lap speeds. The whole driving position and steering wheel position encourages a relaxed approach to driving these cars quickly, and it was important to build up speed steadily. The gearing is relatively low (as referred to above) for Rockingham, although under the circumstances this was probably not a bad thing. Progress through the gears is swift as the car settles into a steady 3500 rpm top gear rhythm. At this speed, there was no need to lift on the approach to the corners, again indicating that speeds were way off racing pace. Input to the steering is relatively small and reflects the long, steady radius corners. Even at these steady lap speeds, the proximity of the wall dictated by the need to open out the curve and the subsequent noise levels in the cockpit at turn-in and exit points soon conjure up one of the iconic in-car experiences and add to the desire to speed up. Three more laps bring a steady increase to a 5000 rpm peak in a straight line, now definitely requiring a long lift on approach to the corners. Progressively earlier application of the throttle on the exit of the corners now starts to promote wheelspin, which if pushed would lead to losing it (oversteer) on exit, and while slightly more controllable than a car that is intent on a tight (understeer) entry, this is now the point where visions of an abrupt visit to the wall can be experienced and would be most unnecessary. The #7 has certainly been lucky for today.

Conclusion

It was good to have the opportunity to run the car on both a road course and an oval, and sincere thanks has to be given to the owner, John Truslove, Mike Luck of Classic World Racing—who prepped and delivered the car to both venues, and lastly, but not least, the circuits and the marshals at Silverstone and Rockingham. I’m not too sure we’ve achieved this in the past, but it has been a great eye-opener into the differing worlds of road and oval racing, if not at full competition speed. As for the car, it is clear that this Camaro, originally built by Banjo Matthews, was the right tool for the job. History shows that the long relationship between the Camaro and the IROC series confirmed the car as an all-round racer irrespective of the type of circuit. Our driving experiences were satisfactory to show it was the input and ability of the driver that would make a difference, not the car. While the weather conditions were problematic, they served as a leveller and parity for both test drives. Yes, there are those who would say the Chevy rather than the Dart engine would have made a difference, but our test viewed the handling of the car rather than the power source. It’s good to see these cars restored and racing around the circuits stirring memories of a bygone era. Did the IROC series prove who the greatest driver of the day was? I think the jury is still out on that, but it did give some close and exciting racing, and I’m sure all of those who took part would do it again at the drop of a hat.

SPECIFICATIONS

Engine Traco 350 Chevrolet V8 (period) / replaced with a 5.7litre Dodge Dart

Fuel 102-octane

Gearbox Borg-Warner TX10 4-speed

Brakes Hurst-Airheart 12inch dia. Vented discs all round

SuspensionMonroe shocks all round, Front: “unequal length A-arms, anti-roll bar”. Rear: live axle on long trailing arms and Panhard coil springs.

Track 65inches front and rear

Wheels Norris Industries 15 x 9.5

TyresGoodyear

Wheelbase 108 inches

Length 180 inches

Width 80 inches

Height 50 inches

Ground clearance6 inches

Weight3013lbs – dry

Resources / Acknowledgements

Bibliography:

Young, A., Camaro, Motorbooks, 2000,

ISBN: 978-0760307830

Leffingwell, R., Porsche 911-Fifty Years, MBI, 2013,

ISBN: 9780760344019

Various issues of Car & Driver, Road & Track, Autosport and Motorsport.

Vintage Racecar would like to express sincere thanks to John Truslove, owner of the Camaro, for loaning us his car for this profile, as well as Mike Luck of Classic World Racing, Redditch, UK for prepping and transporting the Camaro.

Additional thanks to the staff and marshalls of Silverstone Circuit and Rockingham Motor Speedway for all their assistance and support. Special thanks to Jens Torner of Porsche Archive.