1936 Alfa Romeo 2900A Mille Miglia

Photo: Peter Collins

For those of you who insist on having your car stories simple and uncomplicated, you are about to be disappointed…again! The incredible machine you see on these pages had no less than four (and possibly five) incarnations and was yet another example of the casual Italian car mentality in the 1930s. This car was sold “new” to one Alfredo Brioschi on December 4, 1936; its luxurious sporting 2-seater body was painted in snappy 2-tone colors and bore the Milan registration number 55316. The car also bore a chassis plate with the number 412006, and it was indeed the car which had appeared on Alfa’s stand at the Paris Motor Show only a month before. If you look on page 306 of the “Alfa Romeo Bible,” Luigi Fusi’s masterwork on all Alfas ever produced, you will see this very car with that registration number.

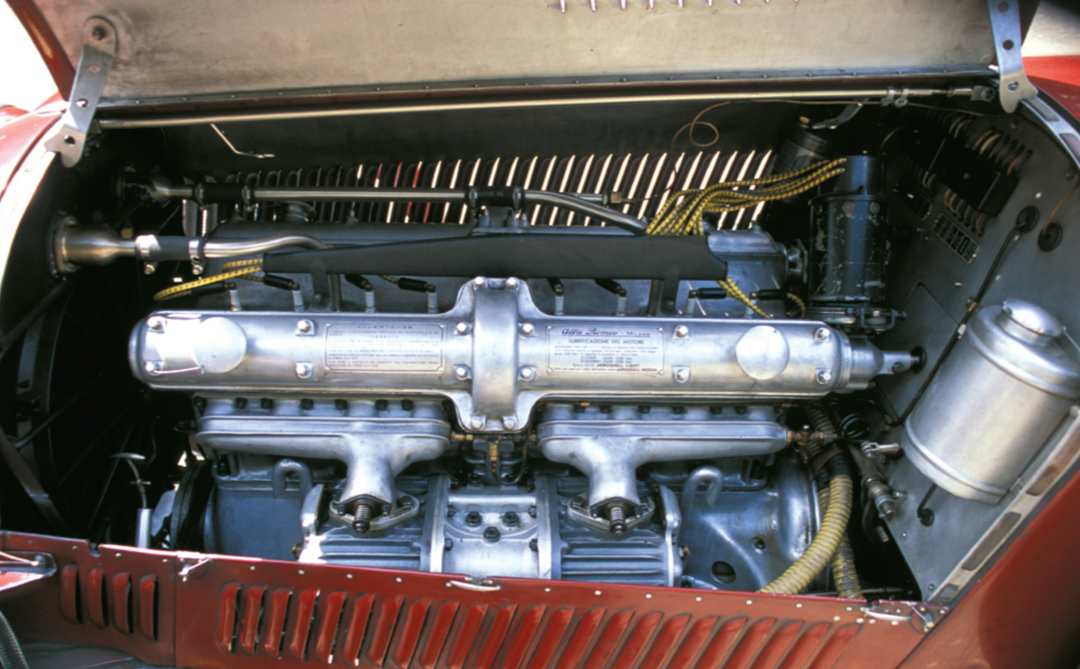

And if you go back two pages, you will see it again, except you won’t know it’s the same car until I tell you this tale…and certainly Mr. Brioschi didn’t know it! Before Mr. Brioschi purchased it, this car had already had at least one and possibly two of its lives! Whether he thought he had purchased a 2900A or a 2900B is unknown, but for clarity’s sake, the designation 2900A refers to the first 10 chassis built and the engine specification which quoted 220 bhp at 5300 rpm.

Photo: Peter Collins

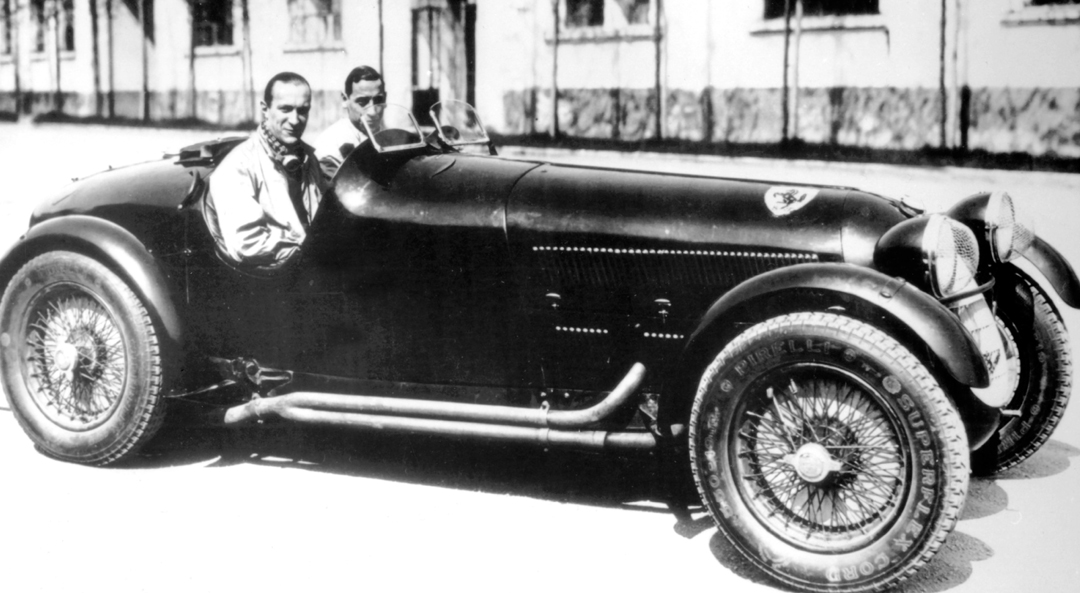

What the wealthy Italian gentleman didn’t know was that his car had a few hard miles on it already, but the story goes back a bit further. In April 1936, Alfa Romeo entered three 2.9s in that year’s Mille Miglia. These cars had very functional spider body-work and cycle wings and were christened with the nickname Botticella, which means cask or keg and was a reference to the car’s shape. The cars featured twin aero screens and were driven by Brivio/Ongaro (#75), Farina/Meazza (#82) and Pintacuda/Stefani (#79).

Photo: Peter Collins

Brivio started eight minutes ahead of Pintacuda, but the previous year’s winner caught up with him and went past somewhere on the Futa Pass and almost immediately had carburetor problems and lost half an hour before the cars reached Rome. By this time, Clemente Biondetti in a privately entered, modified Tipo B had taken the lead from the works Alfas. Eventually, Brivio went on to re-take the lead and beat the other two 2.9s and Biondetti, but it wasn’t an easy win. His battery came loose and fell off at Peschiera (near the finish), however another old Alfa stalwart, Count Trossi, was a spectator at Peschiera and offered to drive his Packard behind the Alfa to provide light for the final 20 kilometers! Farina finished just thirty seconds behind.

After the Mille Miglia, two of the team cars, supposedly chassis 412002 and 412004 (the victorious Brivio car) were registered for the road. These two were then sent to South America. Early mistakes in the records meant for some years it was not clear which cars went to the Brazilian races as 412004 is listed as hav- ing been at both Sao Paulo and Spa at the same time!

However, in August, Farina recorded a win at the Freiburg Hillclimb in 412004, so in fact, the Mille Miglia winner had not been sent to South America after all but had been the car driven by Farina/Siena in the Spa 24-Hours where it retired in the 9th hour. The other factor which makes identity difficult were the rules which governed particular events of that era; the cars some- times ran with cycle fenders, sometimes without, the headlights were removed on occasion, and the cars switched back and forth between one or two aero screens. Case in point, at Modena in September, Severi drove 412004 and finished 4th in a car with no lights, wings and one screen.

A little earlier I mentioned a possible additional incarnation, which now enters the story. At the end of the 1936 racing season, 412002 was re-bodied, had its chassis number re-stamped 412007, and appeared at the Milan Auto Show in October. A second car was also on the stand, chassis 412006. On the rear engine bearer (on the driver’s side) was a chassis stamp with the number 412006 with the 6 clearly stamped over the top of a 4. In addition, the original Scuderia Ferrari number given for 412004 – 54 – could be found on the central casing between the superchargers. This car was then re-bodied, yet again, for the Paris show, and thus already had two short but dramatic chapters in its life before Mr. Brioschi bought it: “…never raced nor rallied.” If this weren’t bad enough, Alfa Romeo, having re-numbered and sold off the 1936 cars, laid down a batch of new Botticella cars for 1937, and gave them – wait for it – chassis numbers 412003, 04 and 05, repeating the previous year’s numbering!

Photo: Alfa Romeo

Life as a road car

Brioschi had the car for five and a half years and sold it in 1942 to Vittorio Roncoroni, who in turn sold it on to Jean Studer in Switzerland in 1946 or 1947. Studer raced it regularly and also bought a second 2.9 (incidentally, another car with multiple bodies!). Studer thought 412004 was indeed 412006, but the car remained fairly original to its Paris Show identity while he owned it, though it had acquired larger superchargers. Studer then sold it in 1947 to Hardy Fortmann who raced it from 1947-1949. The car was sold again, this time to Alfred Senften who had Martin of Berne re-body it with a much lower and lighter spider body with a circular grill and cycle wings that turned with the steering. (Senften was one of the first people in Switzerland who had a business installing central heating, and he used the car to trans- port oxygen bottles and welding equipment!) Hans Matti saw the car in 1964 and finally bought it in 1971, and from that time, it appeared in many Swiss vintage events. The engine had a major rebuild during his ownership and he enjoyed the car for many years. It then went to France and then to the U.K. about 10 years ago and is now owned by Matt Grist.

Matt and his father, Paul Grist, use the car regularly in historic events, and perhaps the ultimate glory shone on them at the 2002 Historic Le Mans 24-Hours when the father/son duo won each of their four races during the marathon classic, thus, winning the class and the Alfa Romeo Award. Not to mention bringing a small piece of Alfa history alive at the Sarthe where the Milanese team did so well in the pre-war races.

On a sunny and cold winter’s day, we gathered at Grist’s English home to try the car on the road…where else should you drive a proper road-racing machine? In addition to filling me in on some of the car’s history before I got behind the wheel, Paul also relayed an interesting story about one of his and his son’s many adventures on the Mille Migla Retrospective with their Alfa Monza. Apparently during one of the Mille Miglias held in the early ’80s, Paul and his then teenage son, Matt, pulled up at a roadside halt near Modena. An elderly man in a dark suit and dark glasses got up from the table placed near the road for his comfort and wandered over to start an elegant reminiscence of the car in “the old days,” with genuine tears in his eyes. As the Grists departed, Matt asked Paul “Who was that old geezer?” The reply: “Enzo Ferrari.”

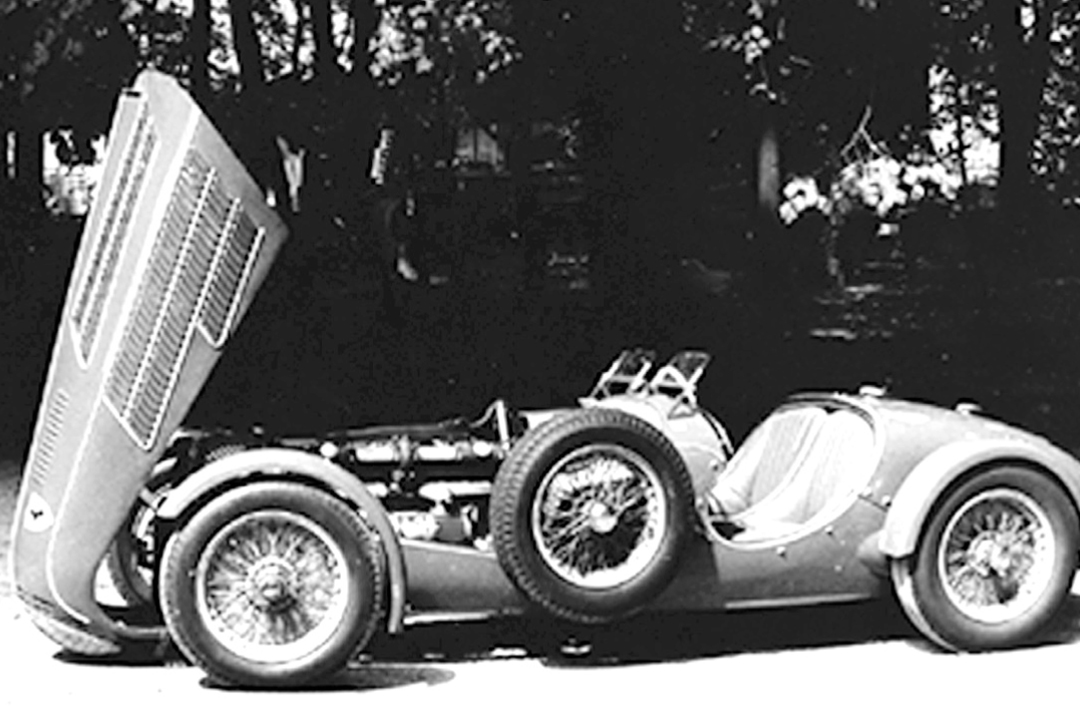

As relating to the Mille Miglia-winning 2900 Paul explained, “None of the original Botticella bodywork survived, and when we got this car, we had to think about what to do with the strange Swiss Martin body, and whether we should have it bodied as one of the sporting 2-seaters as the car was at the Paris Show or whether it would be best with the original 1936 Mille Miglia body. Simon Moore owns 412002 and he found the sports body on a strange Jaguar-powered device and re-united that with the chassis and restored that body. During that time Simon was doing a lot of research on the cars and, we confirmed pretty much that the 412004 could not have been out to Sao Paulo and sent back in a short period of time. That’s more or less when we decided to build a Botticella body. We found out from Simon that the car which had been 412005, a spare chassis, became 412013 and that too had been owned by Jean Studer and he had put a Martin body on that as well.”

“The car came to me through France after Matti had it for some twenty years. The car was mechanically totally original. It has its original engine, unusual for a racecar of the time. I went through it and then did the things which needed to be done but that was not a lot. It had its original block. Being sporting in my aspirations, I went for the body it has now as I didn’t really want a boulevardier car as the second body was. I liked the idea that you could take the wings off and run it as a Grand Prix car or as a sports car; it’s a lovely dual-purpose car.”

Driving the 2900A

My first run in this car was all about getting familiar with its quirks and characteristics, mainly that it would jump out of first gear if not held firmly in place. The second run was about driving.

Photo: Ed McDonough

If you have never heard the whine and whoosh of a pair of superchargers on a massive Alfa racing engine, then you have missed out, and it’s worth scouring the Internet or eBay to find a recording! I like the sound when it emerges from a Bugatti or a Bentley, but the Alfa is in a league of its own. This car is so visceral. There is a huge three-spoke wheel right in your face, no more than fourteen inches away, behind which is one of the two separate aero screens as fitted on the Mille Miglia winner. Ask yourself what car can provide such a physical and sentient experience and the 2.9 has to be very near the top of the list.

The ignition key is a pull device which makes those 8 cylinders burst into life and promise an exciting trip down a damp, leaf-strewn country lane. You push in the key for pumps and electrics, and there is a push button starter and a magneto on/off switch. The speedometer reads to 240 kph and also incorporates four ancillary gauges: oil, water temps, and a lovely old clock. To the left of the speedometer is the rev counter, which reads up to 6000 rpm and is placed in front of the passenger to keep him or her amused presumably. Other items include a hand throttle and various light switches. The fuel tap is located to the right, and the exhaust pipe on the right is near enough to the driver’s elbow to be worrying but it’s protected with period wrapping so that you don’t have to worry too much. But people did get burned on those things!

Photo: Alfa Romeo

Once settled in, there are a number of surprises. What on the surface looks like a fairly heavy car turns out to handle and respond as if it were several hundred pounds lighter. The gearbox is straight forward and easy to adapt to, making it possible to use the acceleration even on our open public road. While the car has the look and feel of something wild, it is docile in the nicest sense of the word, presumably why it performed so well at Le Mans a full 67 years after it had been built. I recall Paul and Matt sliding the rear of 412004 out of Arnage with consistency and verve and thought then that the car must be very predictable. While there would be no hanging out of the tail by me on these Essex country roads, the controllability was evident. What really requires management is the driver’s urge to stay hard on the throttle…you just want to go on listening to that exhaust howl in your left ear.

What I wasn’t getting on this test was the top end experience but rather a closer relationship with pre-war Alfa handling and braking. Grip was provided by the large. Engelbert Racing 7.00/18 competition tires on the rear and 6.00/18 on the front. The car stands tall on these 18 inch rims but in no way feels uncomfortable. There is no roll or lack of precision, and the car can be lined up for a corner and neatly powered through on the throttle. This was truly an opportunity to savour. Once the distractions are dealt with (i.e., the central throttle and the gearbox’s tendency to jump out of first gear), there is time to take in the many features such as the fine leather saddle bags on the left side, cushions for the driver’s and passenger’s legs, and the luxurious leather seats. I found myself quickly acclimatizing and was soon able to enjoy the utter pleasure of feeling the torque in second and third gears as you press that central throttle towards the floor (The car even has a tasteful leather covered grab handle on the passenger’s side if he or she thinks you are enjoying the torque too much).

The gear pattern is slightly unorthodox, with first being over to the right rather than on the left side of the box, and reverse takes some learning but that old Alfa transmission is a miracle of strong engineering. The multi-plate dry clutch was not at all temperamental, which is supported by the fact that the Grists have taken this car on tour many times. The independent suspension on the 2.9 was ahead of its time, making this the ideal car both for so-called sprint and endurance races of the period. Much of what Vittorio Jano was learning as he developed the 8C-35 Grand Prix car was incorporated directly into the 2.9. Front suspension is by double trailing arms with enclosed coil spring damper units, and rear suspension is by swing axle, radius arms and a transverse leaf spring. This remains consistent through the production of both the race and road cars of the A and B series, though fine details on these cars do tend to vary. While the specifications say the 2900A had a frame length of 2.75 meters, individual cars tended to differ slightly.

Buying and running a 2.9

The Grists say that maintaining their car is a relatively easy business, and it is very, very reliable. On the other hand, they are amongst the elite of pre-war Alfa Romeo specialists and they can handle anything that comes up. A 2.9, either A or B, rarely comes on the market so you are not going to have much of a dilemma about choosing one. However, according to Simon Moore’s wonderful “Immortal 2.9,” now some 17 years old, not all the 2.9s have been accounted for, and back in 1986, he was theorizing about something stuck in a barn somewhere. It may still be out there. But how would you put a price on a machine that became a national icon in Italy after winning the Mille Miglia and whose teammate was the great Farina who raced this very car himself. It was Farina who chased this car mile after mile in the desperate and ultimately unsuccessful attempt to take the prize from the taciturn Brivio. Then there’s the magic. Brivio’s friend provides lights for the final miles and still Farina can’t catch him. You can buy that history, but at what price, and does it matter?