1953 Austin-Healey 100

Is this the ideal sports car of the 1950s? The car that sparked thousands of people into thinking they could buy a production machine and go racing? This 1953 Healey did just that, essentially a production car that found glory at Le Mans and the Mille Miglia. But is this racer still a true “street machine”? As the car was being prepared for its return to the Mille Miglia last year, I was able to put Vintage Racecar behind the wheel to see if it was still capable of high-speed work on public roads.

Healey Cars

Donald Healey was an avid competitor in the prewar years, and a regular participant in the Monte Carlo Rally in a variety of cars. He was doing experimental design work at the Riley Company, and then, in 1934, moved to the Triumph Motor Company. There, he was responsible for the design of the Gloria and the Dolomite models and he would use these in the Monte Carlo Rally, as much for testing his design as for his own enjoyment. He was general manager at Triumph at the outbreak of WW II, then moved to the Humber Company, working on the development of armored cars. During this period, he met Ben Bowden, A. C. Sampietro, and James Watt, and this quartet came up with the idea to design and build their own car—an ambitious project during wartime. Bowden sketched ideas for different body styles, and Sampietro worked on suspension. In 1944, they tried to convince Triumph to build their car but were turned down.

However, they were offered the chance to base their work at Westlands, the Humber distributors in Hereford. They had assistance from Westlands in getting supplies and had their initial bodies and frames built by Westlands. The group then moved to Warwick in the summer of 1945 and started to assemble the first car with a Riley engine and gearbox. Roger Menadue joined the company as an engineer and the prototype “Westland” was launched in January 1946. The rather basic chassis design of the Westland remained the design for Healey cars until 1953. As head of the company, the cars became known as the Healey Westland and then the Healey Elliot. Johnny Lurani and Teodoro Serafini shared a Healey Elliot in the 1948 Targa Florio, a 600-mile event around Sicily. They finished 13th after a long stop to repair a broken chassis, and Healey competition cars were on their way.

The Healey Silverstone followed in 1949, and then came the Nash-Healey in 1950. Many of the cars were very successful in long-distance races and rugged international rallies, and Healey quickly became well known for producing cars fit for both roads and racing. Healey took these events seriously, and Nash-Healeys were run regularly at Le Mans. A number of cars with special bodies were also built for road use only: the Healey Duncan, the Sportsmobile, the Tickford, the Abbott, and the Sports Convertible.

These were all rather expensive cars built in small numbers. Donald Healey, working with his son Geoff, finally decided to design a new car which would be a sports machine, light in weight, compact, simple in layout, and which would also use a strong, unmodified engine that was not costly. The new car would look good, have impressive performance and handling, and this was the Healey 100…which, of course, would later become the Austin-Healey.

The Healey 100

When Donald Healey’s Healey 100 appeared at the London Motor Show in October 1952. It had a fabulous reception: it went on to win the Grand Premier Award at the World’s Fair in Miami, and then the same award at the New York Motor Show, and it was voted as the International Show Car of the Year.

The car was designed to be something special, but it was also very much influenced by practical matters. The Riley engine was about to go out of production, and Healey wanted something lighter and cheaper, and chose the Austin A90 Atlantic unit. Geoff Healey himself designed the chassis. They only managed to complete the first car in time for the London show, but had built a few chassis. The first 25 cars were built at Warwick, and after establishing an agreement with Austin, the remaining production run would be constructed at Longbridge.

When the show car made its appearance, it was immensely popular, and the order book soon filled up as the price was set at £750, something within the reach of many people. However, the Warwick factory did not have the facilities to cope with large-scale production. Sir Leonard Lord was the Chairman of the Austin Motor Company, and he had been involved with Donald Healey since 1951 when Healey started using Austin components. Sir Leonard made the offer to Healey at the London Motor Show to take over production at Longbridge, and the new car would then be called the Austin-Healey 100—the 100 representing the £100 discount from the original £850 price proposed by Healey!

The new Healey sports car was a departure from previous designs. The new chassis was to be a two-seater and it would have two straight 3-inch-square box-section side-members running in parallel for the length of the car, 17 inches apart. These were braced by parallel cross-members with the steel floor attached to the cross-members. It was a compromise between traditional box-section and integral chassis/body construction in modern saloon cars. Coil and wishbone suspension would replace the trailing links in the front, with lever arm hydraulic shock absorbers. The rear was similar with half-elliptic leaf springs, and one advantage was that the suspensions were built from standard Austin parts. The final choice of engine for Healey was the Austin A90, which produced 90 bhp at 4,000 rpm. In basic form, this was not a very exciting engine, but was rugged and reliable and would be a good starting point for tuning.

The Austin A90 4-speed gearbox was also used on the original prototypes including the steering wheel–mounted switch for the Laycock overdrive. When the first cars were tested, Healey discovered that the car wasn’t well suited to the very low first gear, so first gear was locked out and the production models had a 3-speed box with overdrive, with full synchromesh. The 2.7-liter engine, 3-speed gearbox, and overdrive on the top two gears proved a good combination.

Though the mechanics were well thought out, it was the lovely two-seater body that caught everyone’s attention. The simple but comfortable cockpit and reasonable size boot were very attractive, and the body shape remained similar for many years.

Photo: Peter Collins

NOJ 392

By February of 1953, three of the first batch of 20 “pre-production” cars built at Warwick were complete. The next cars completed were the four “pre-production competition” cars. Experimental engineer Roger Menadue was in charge of building these cars that would look like the production machines but would be lighter. The plan for these cars was that they would be raced at international events and attempt to set new distance and speed records. They were also used on promotional tours as Donald Healey understood the importance of competition in selling production cars in that period.

In reality, only 19 rather than 20 cars were built at Warwick…the first 4 preproduction cars, then the 4 competition cars, numbers 5, 6, 7, and 8, and then the remaining pre-production vehicles, with number 10 never being built for some reason. “Our” car was number 6.

The competition cars, built by Menadue’s team of eight in the new experimental workshop, looked very much like the production cars, although the Jensen-built bodies were of Birmabright alloy material. The first three cars were supplied with bumpers, and these were in a chemically polished alloy rather than steel. The fourth car to be used for speed records was even lighter. All four were painted in what was known as Dockers’ metallic light green, because Donald Healey was superstitious about British Racing Green. The interiors were done in dark-green leather and the dash carried a stamp with the car’s numbering. The 15 pre-production cars were painted in the classic pale metallic blue.

The engines in the competition cars had special nitrided crankshafts, racing pistons, lightened flywheels, and a special camshaft to provide higher lift. There were stronger valve springs and were eventually fitted with cold-air boxes and 1.75-inch SU carburetors, so power was up to 103 bhp at 4,500 rpm. There was a Borg and Beck racing clutch. The gearbox was the same as the Austin Taxi! The high-ratio overdrive gave the engine much greater flexibility. The radiators, also aluminum, were very light, and the car was fitted with Girling brakes, 11.2 x 1-3/4-inches, with Mintex M20 linings. The competition cars also had a thicker front anti-roll bar, long-range fuel tanks, and Dunlop Racing tires.

After the cars had been built at Warwick, series production began at Longbridge in May 1953. The new production model was given the factory code BN1, and this code was used more in later years to distinguish the early cars from the BN2 series that was introduced in August 1955. The BN2 would have the 4-speed BMC gearbox.

Going Racing

NOJ 392 was the 6th of all the cars built, 2nd of the competition cars, and as it happens, the only one to remain in its original specification all through its life.

One of the prototypes was taken to the Jabbeke Highway in Belgium, where it took records for the flying kilometer and mile. One car was then sent on the difficult Lyons–Charbonnieres Rally in March 1953, where it showed strong potential before the suspension broke after hitting a deep hole.

The Healey team had already had Mille Miglia experience, so two cars were made ready for the 1,000-mile event. Bert Hadley and Bertie Mercer were to drive NOJ 392 and the second car, NOJ 391, was in the hands of Lockett and Reid. There were 480 starters and the Hadley/Mercer car was number 552, as it is today, since the car has been restored to the condition it was in for that event. Unfortunately, both cars had clutch problems from the start. The high speeds built up gearbox oil pressure, which was forced onto the clutch. NOJ 392 broke its throttle linkage and was retired on the first 180-mile stage from Brescia to Ravenna, a stage that claimed a total of 64 cars. The second Healey managed to keep going, only to retire some 100 miles from the finish. However, a number of lessons were learned that helped make improvements in the production cars.

The Mille Miglia was won that year by Giannino Marzotto and Nearco Crosaro in the Ferrari 340MM followed by Fangio and Sala, Fangio having his epic drive in the Alfa Romeo 6C 3000CM with a broken steering arm for the last 100 miles.

As soon as the Mille Miglia was over, the cars were returned to be prepared for Le Mans, and three cars were sent. NOJ 391 and 392 were the official Healey entries and 393 was the works spare car. In the days before the race, team members suffered from food poisoning and, then, after practice, NOJ 391 was seriously damaged in a road accident on the way back from the circuit after scrutineering. The organizers refused to allow 393 to be substituted for the damaged car. There are then two tales of what happened…one was that they were forced to totally rebuild 391 so it was road-worthy, and the second was that 393 was rebuilt exactly to the specifications of 391; and it does seem that indeed 393 was the second car in the race. There are still arguments over this point. Driver Gordon Wilkins’s wife was injured in the crash and dentist Alfred Moss, Stirling’s father, set to work to improve her personal damage.

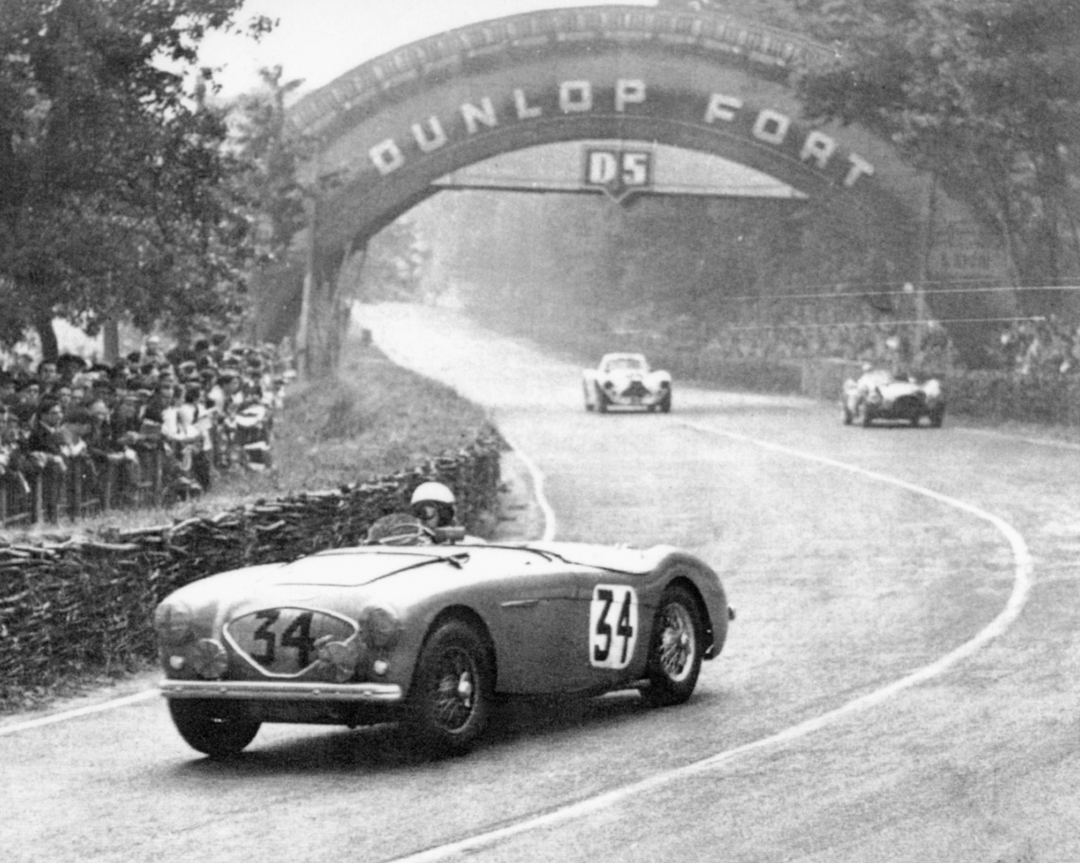

NOJ 392 was driven by the experienced team of Maurice Gatsonides and British motorcycle racer Johnny Lockett, while the second car was in the hands of Frenchman Marcel Becquart and British journalist, the late Gordon Wilkins. The intention at Le Mans was to show that the cars could run reliably at high speed with a minimum of trouble, and that is exactly what they did. Gatsonides and Lockett in NOJ 392 finished a very impressive 12th overall and 2nd in the Sports 3000 class, at an average speed just under 90 mph. The second car was two places back in 14th and was 3rd in the class, a Frazer Nash separating it from its teammate. This was especially impressive for what was being called the “world’s cheapest 100 mph sports car.”

One of the competition cars then came in 10th at the Goodwood Nine Hour race later in the summer of 1953, and Healey led a group of drivers who took over 100 records at Bonneville. A tuned version of the 100 managed a time of 142.6 mph over the mile at Bonneville.

NOJ 392 Continues

After Le Mans, the team returned to England and NOJ 392 was the car used most often for test reports by the national and specialist press. The car reached 119 mph, and was tested with its windscreen and top down, which later led to some owners of the production models being concerned that they could not get quite the same performance.

A letter from Geoff Healey to the then-current owner in 1981 stated: “The car you have is NOJ 392, the car that ran at Le Mans and will be the only one of the first 1953 special test cars that remained as a 100. 391 and 393 developed into 100S cars. The car that was in the accident after scrutineering was rebuilt from the ground up, body work by Jensen. NOJ 392 had 11 x 2-1/4 Girling drum brakes at Le Mans, if you want to restore it to Le Mans trim. The Girling disc brakes went on in 1954. The front callipers were larger than the rear. They were a one-off set similar in design to the rear.”

In its role as a development car, NOJ 392 was sent to Girling to test their new disc brake system to compare it with the Dunlop system. The car was used frequently by Roger Menadue, almost as his personal car, and with which he would tow a small boat. It was used by Geoff and Margot Healey as their wedding car which they drove to Italy. Donald Healey then gave it to Roger Menadue who used it as his daily car until 1962. The car was registered in the name of the Austin Motor Company from 1953 until 1958 when it was changed to the Donald Healey Motor Company. In 1962, it was finally sold out of the company to John Berry; in 1966, it went to John Shuttlewood, to Jonathan Roberts, to Geoffrey Orme, back to Jonathan Roberts. Malcolm Hay owned it from 1967 to 1970; then for nine years, it belonged to B. Dermott. It was sold to John Gray in Australia in 1979, and it was Gray to whom Geoff Healey wrote to clarify details of the car. It was then sold to another Australian, Warwick Sell, in 1993, and he owned it until it was returned to the UK. Warwick Sell and his brother Cameron did some races with the car at Wakefield Park in late 1994, and then the Healey Company in Ringwood, Victoria, did a restoration, although the car was still in remarkably original condition. When the restoration was complete, the car won the Austin-Healey Motor Club Concours outright. There was very little rust or damage in spite of the fact the car had been off the road for sometime in the ’70s. All the original components were refurbished rather than replaced. Roger Menadue was reunited with the car in Melbourne, after it had been restored, and confirmed the early history.

Testing for the Mille Miglia!

Cars International put the car in exactly the condition it was in for the 1953 Mille Miglia, complete with race number.

When Paul Osborn and Jonathan Kaiser said it was available for “testing,” it was clear that it needed to be run in conditions very similar to that experienced in the great Italian road race. So, a mix of quick roads, normal traffic, demanding corners, and even cobblestone streets were found to create just the right conditions. And all these roads were in the middle of London!

On a bright Saturday morning, NOJ 392 roared out of its home in South Kensington. Well, it took a little fettling and the addition of some more fuel to prime the carburetors before it would get started on this cold day. The choke needed to stay on for several minutes, but it then settled down and ran smoothly for the entire test.

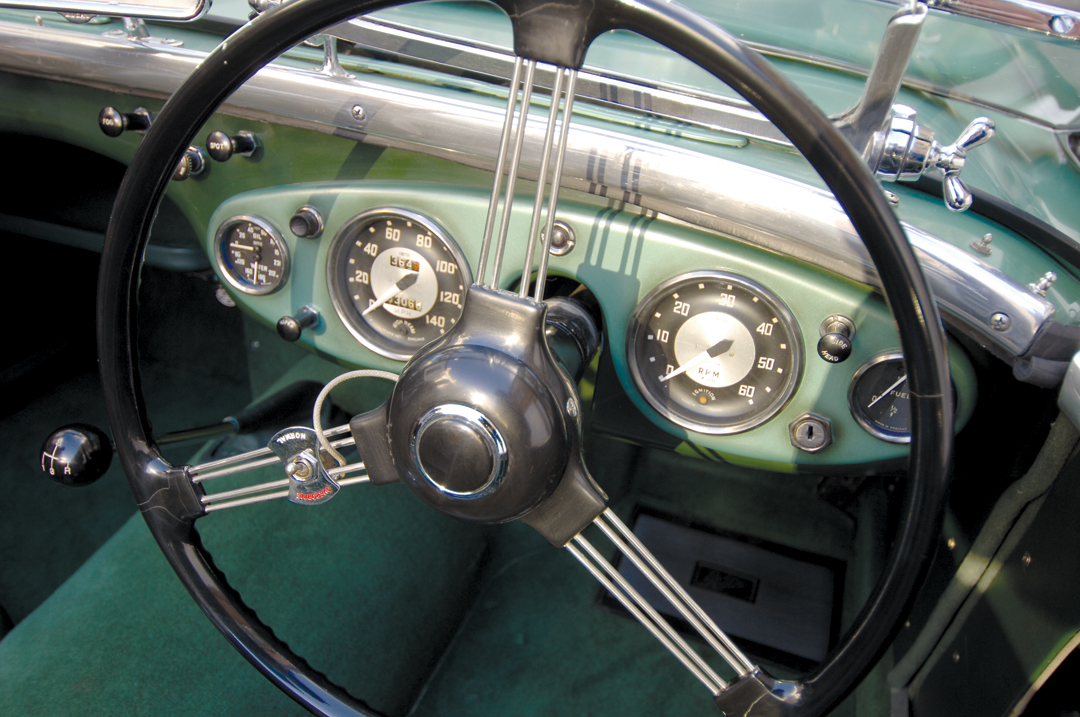

I never drove an early period Austin-Healey, being a Jaguar XK120 person way back in…1961…my first “proper” sports car. The gearbox took me by surprise, discovering the 3-speed and reverse box rather than a 4-speed, although, with the overdrive, it was absolutely fine to work with, and in traffic was totally adaptable to conditions even without using the overdrive. Before driving off, I had a good look at all the details…the chassis plate reading chassis SPL225B, and the all-important build number AHR6, the six indicating it was indeed the 6th car built. It also had the original identity information, number IB 36876, as well as the impressive original dash plaque from Le Mans. The leather interior is not only good looking but very comfortable. The choke knob is tucked under the dash, and so is the direction-light switch…which is really well hidden!

The rev counter reads to 6,000 rpm and the speedometer reads to 140 mph, and there are oil and water temperature and fuel gauges. The three-spoke steering wheel has the overdrive switch right in front off you for easy use…you don’t have to take your hand of the wheel. On Dunlop SP Radial tires, 165 x 15-inches all around, the car is precise with a very light feel, the steering quite neutral in most conditions, with a touch of understeer under heavy braking, but still very manageable.

The exhaust exits near the passenger’s door, so it is very quiet for the driver, though there is a lovely boom as we accelerate hard through the canyon of buildings which is London, going up through the gears and chopping through traffic as we move slightly east and north to head across the open road over Hyde Park. Here, NOJ 392 eats up the series of bends, off-camber road sections, and barks as it leaps away from other traffic. As we find a quiet part of the park, I have gotten used to the gearbox. Each gear has to be taken deliberately; the lever doesn’t slide into gear, it has to be taken there, though after ten minutes it can be forgotten. Reverse is up, out to the right, and back, again easy once you have found it.

The car was at its pure best winding up through first and second gears, flying through the sun-dappled fallen autumn leaves, flinging them through the air as the car rushed past. With the windscreen at its adjusted angle, the aero screen is all that is needed as the green machine slides through the air. On a deserted piece of this major park in the center of London, we got nearer to the upper end of the speed limit—a truly great feeling. Then, it was back through the busy areas, nipping past cars and pedestrians, all with mouths open. There were several places where hard cornering could be tested as it should be. The Healey sticks firmly to the road with no loss of control at the tail end. Then, back through that hidden area of mews with cobbled and narrow roads.

The Mille Miglia was re-created as the car leaned heavily being forced into left and right hand corners, braking as it should, all the gauges working, and a few spectators gathering to watch the fun.

Very few people would know just what an important and valuable bit of history was being driven past them. The car, though it was ready for the 2008 Mille Miglia at the time of our test, was on the market for a very significant figure…and sold for some £350,000…there can be very few cars so right for the events that today commemorate the historic past. This is a truly great little car…which was what Donald Healey intended it to be.

Specifications

Chassis: Steel box-section frame

Body: Aluminum

Wheelbase: 2290 mm

Track: Front 49.5 inches; rear 47.2 inches

Suspension: front: independent-wishbone, coil springs, lever-arm damper, anti-roll bar, rear: live axle, semi elliptic leaf springs.

Weight: 940 kg

Engine: Cast iron four-cylinder

Displacement: 2,752-cc

Bore x Stroke: 88.8 mm x 111.1 mm

Carburetors: 2 H6 SU

Power output: 110 bhp @4500 rpm

Gearbox: Austin 5-speed including overdrive plus reverse

Steering: Burman cam and lever

Brakes: Girling discs

Wheels/Tires: 15-inch Wire spoke center lock wheels Dunlop Radial 165 x 15 tires

Resources

Many thanks to Cars International for the opportunity to experience this bit of history.

Healeys and Austin-Healeys, Peter Browning and Les Needham, Foulis 1970, ISBN 0 85429 101 6.