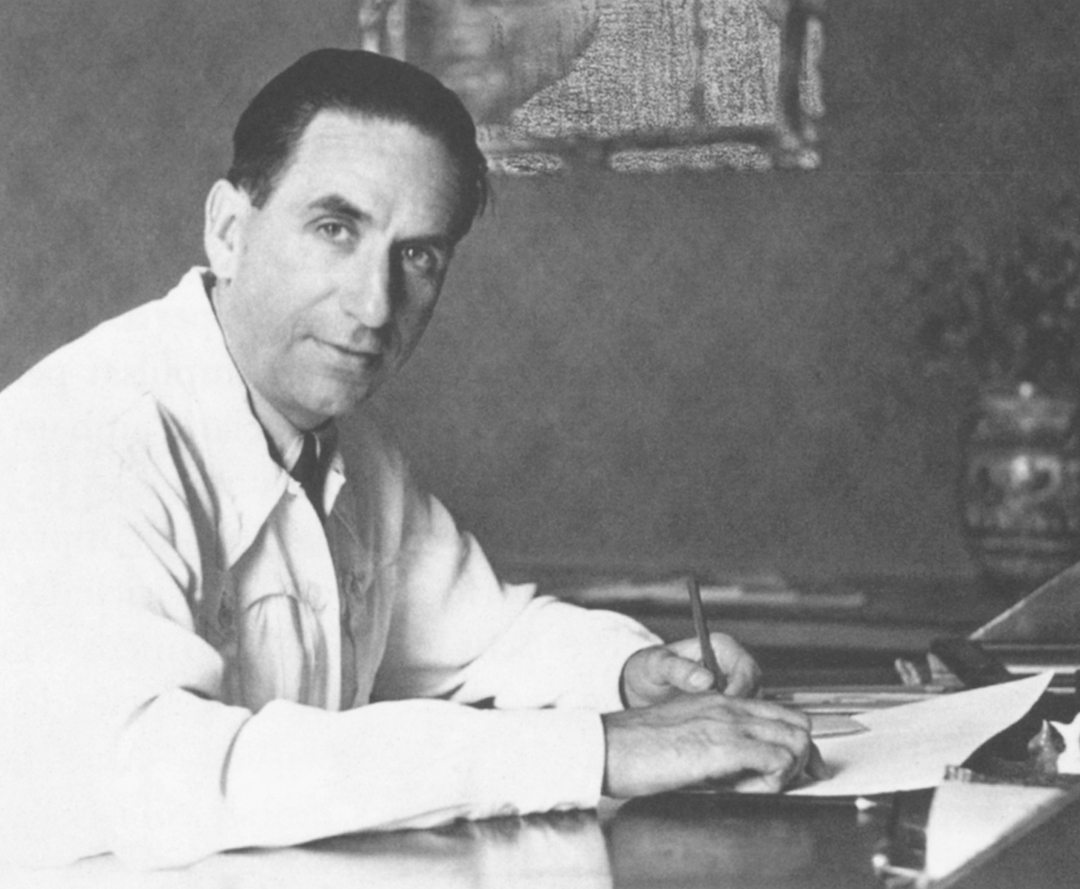

In order to understand the Pegaso story, it’s first necessary to understand the man behind the car and the tumultuous times that he lived in.

Wifredo Pelayo Ricart y Medina was born in Barcelona on May 15, 1897. By 1918, he graduated from the Barcelona School of Engineering as an industrial engineer and went to work for a local Hispano-Suiza dealer, before starting his own company in 1920 (Sociedad Anomina Motores Ricart y Pérez). Ricart’s first car debuted in 1922 and featured a 1.5-liter, four-cylinder engine with twin overhead camshafts and four valves/cylinder. By 1927, a 6-cylinder twin-cam competition car called the Ricart España was unveiled. However, political circumstances in Spain at that time resulted in Ricart closing his company by 1931.

Like much of Europe, the 1930s were a dangerous time in Spain. Right wing Nationalists were exerting great influence in many parts of the country, while the left-leaning Republican government desperately tried to maintain its own strongholds, most notably in large cities like Barcelona. The entire Ricart family, including Wifredo, aligned themselves ideologically with the growing Nationalist movement and its leaders in the Spanish military. However, this left the Ricarts dangerously out of step with Barcelona’s prevailing politics and so, by 1936, the family as a whole fled Spain. Perhaps not surprisingly, Wifredo Ricart quickly found himself in Portello, Italy, having been offered a job to work at Alfa Romeo by Ugo Gobbato (whom he had befriended when Gobbato had worked in Spain for Fiat). While first brought in to work on diesel and aero engines, Ricart so impressed Gobbato that he was quickly promoted to Chief Engineer of Special Projects which, in essence, gave him control over a wide variety of Alfa Romeo departments, including the racing department. Unfortunately, this did not sit well with the racing department’s Enzo Ferrari, who saw Ricart’s promotion as a slap in the face to his good friend Vittorio Jano. The result was Ferrari’s unconcealed contempt for Ricart and anything he did. Historian Griff Borgeson relays a telling story of the duo’s enmity when once Ferrari asked Ricart why he wore crepe-soled shoes—something that Ferrari viewed as being in extremely poor taste. With a perfectly straight face Ricart responded that it was necessary to cushion an intelligent man’s brain. Ferrari took this as an example of Ricart’s arrogance, never comprehending the slight that the sharp-witted Ricart had thrown right back in his face!

After the fall of Mussolini, Italy went on a national witch-hunt in an attempt to purge the country of anyone that was even remotely considered to have been a fascist sympathizer. Whether he read the political tea leaves or not, it is interesting to note that Ricart’s contract with Alfa ended on March 31, 1945, hardly a month before Mussolini was captured and executed. With Italy becoming too dangerous, Ricart quickly returned to Barcelona. Interestingly, it may not be coincidental that Enzo Ferrari was very influential in the purging of fascists out of the Italian automotive industry during this same time period!

Civil War

When Ricart returned to Spain, he found a remarkably similar environment to that which he had just left. In the intervening ten years, Spain had fought a vicious and bloody civil war, resulting in a new fascist government taking over, run by Generalissimo Francisco Franco.

After a decade of fighting fascism across Europe, the world had had its fill of fascism and dictators, and as a result, Spain became something of an international pariah. Not unlike apartheid South Africa in later years, much of the free world avoided doing business with Spain, resulting in the country having to produce many domestic products for themselves. One area where this was acutely felt was in heavy trucks and busses. As a result, the Franco government created the Instituto Nacional de Industria (INI), which in turn created a state-owned company called E.N.A.S.A (Empresa Nacional de Autocamiones, S.A). In 1946, E.N.A.S.A. was set up in the old Barcelona works of Hispano-Suiza, with the directive to build busses and heavy trucks under the name, Pegaso (Spanish for Pegasus, the winged-horse of mythology). Fresh from his service in Mussolini’s Alfa Romeo, where he had overseen much work on diesel engines, Don Wifredo Ricart was the natural choice to head up Pegaso as Managing Director and Head of Projects.

Due to Spain having little or no industrial infrastructure or trained technical sector, those first years for Pegaso were vey difficult. In 1946, Pegaso built only 38 trucks, with all the construction being done by hand. By 1949, that number had increased to only 169 units/year. Despite these low numbers, Ricart did manage to take an antiquated factory—with very little resources, other than cheap manual labor—and produce a very serviceable product. In the process, Ricart set up a technical training center at E.N.A.S.A. that would help educate and train the engineers, designers and technicians that Spain’s growing industrial sector would need. But Ricart’s interests and ambitions were much greater than busses and delivery trucks.

Franco Builds a Sports Car

Ricart still longed to build advanced automobiles like the cars he built at Alfa Romeo. Like so many influential automotive industry leaders before him and since, Ricart saw the educational value that building a sports car would have for his engineering team, as well as the E.N.A.S.A. training center. Fortunately for Ricart, Generalissimo Franco had a complementary problem. His country was suffering from the world’s poor view of Spain. He needed something that could show the world that Spain wasn’t a backward country and that it had industrial potential—investment potential. What better way to spread that message than with a world-class automobile, sought out by affluent “influencers” the world over. Additionally, Franco’s INI was also in the midst of trying to launch a major joint venture with Fiat, to mass produce cars in Spain under the new SEAT (Sociedad Española de Automóviles de Turismo) brand name. In order to do this, Spain was going to need trained labor—lots of it. As a result, in 1950, Ricart was given the go-ahead to begin work on Pegaso’s first automobile.

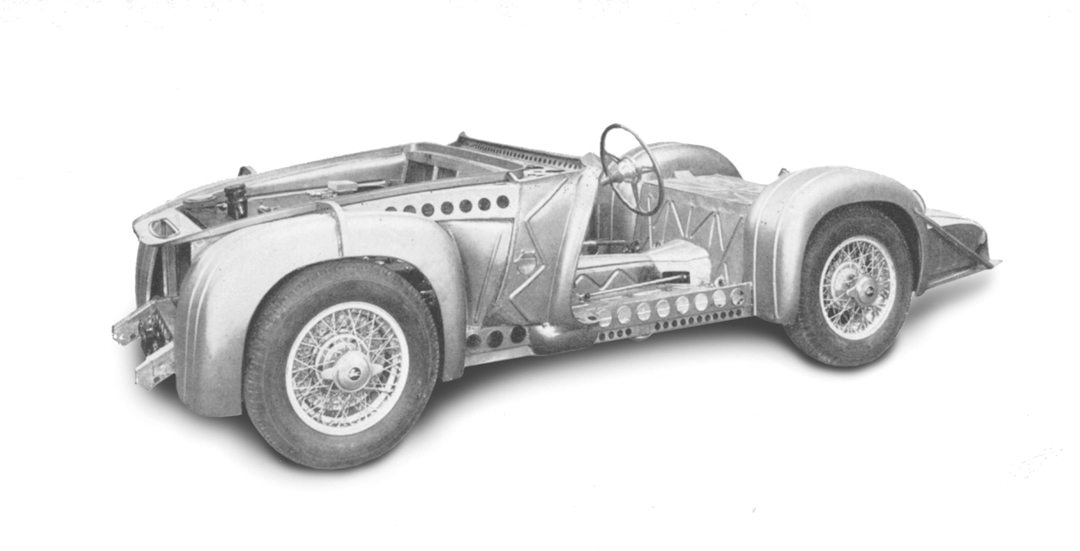

That first car, the Z-102, was debuted at the Paris Salon, in October 1951. To say it was a revelation is an understatement. On the Paris stand were two Z-102s, both a coupé and a convertible, clothed in elegant bodywork by famed Turin coachbuilder Carrozzeria Touring. While both cars looked the part of an elegant sports car, it was under that superleggera skin, where the Pegasos really shined. The short, 91.5” wheelbase chassis was a pressed-steel platform, with reinforced sheet steel box members. When welded together with the firewall, front body pillars and wheel arches they formed one of the first, production unit-body constructed passenger cars. Surprisingly, Pegaso shares the credit for one of the world’s first production unit body cars with Alfa Romeo, who unveiled their 1900 sedan at the 1950 Paris salon as well.

Under the bonnet, the Pegaso dumbfounded pundits with a 2.5-liter, all-alloy, 90-degree, V-8 engine. Despite Spain’s reputation for lack of industrial capacity and expertise, Ricart and his staff had managed to construct a jewel of an engine that featured gear-driven, twin overhead camshafts, hemispherical combustion chambers with two, sodium-cooled valves per cylinder, an integral dry sump lubrication system and the choice of either single or four Weber carburetors. With an over-square bore and stroke of 75-mm x 70-mm this completely bespoke unit boasted 165-hp and 138 lb-ft of torque.

Photo: Casey Annis

Ricart’s engineering tour de force continued from the engine all the way through the powerline. A single, dry plate clutch was mounted onto the flywheel, which then fed power out of an aluminum bellhousing and to the back of the car where it mated with an aluminum transaxle. Inside the transaxle, a 5-speed, close ratio, gear cluster was mounted to the rear of the differential, similar to a quick-change rear-end seen in Indianapolis cars of the day. Uniquely for a passenger car, the gearbox was comprised of bevel-cut, constant mesh gears with dog rings that then fed forward into the ZF limited slip differential. This transaxle unit even had its own 1.8-gallon oil sump and pump for lubrication.

For suspension, the differential unit and half shafts were located by a DeDion tube, with location by radius rods triangulating to the back of the car at the centerline. Suspension at the front was independent, parallel wishbone while the front and rear were sprung by torsion bars, with E.N.S.A.-built shock absorbers. Stopping power came from separate front and rear circuits feeding into vented and finned 12.8-in aluminum brake drums that housed a massive 190-sq.in. of total brake lining material—one of the largest of any production car of its day. Rounding out this impressive package was a worm and sector steering box that yielded an extremely fast 1.6 turns, lock to lock.

Shock and Awe

The public and the motoring press were astounded by the level of sophistication and quality found in the Pegaso. This was made all the more unbelievable by the fact that the car came from Spain, a country considered to be technologically third world at the time. When Ricart was asked why a country so backward and poor, would produce such a fine car exclusively for the rich, he responded: “We are a poor country and therefore we must make jewels for the rich. In jewels, in exceptional products like the Pegaso Z-102, destined for a limited élite and made with great mechanical refinement, handiwork is the most important factor, and only a low standard of living and labor cost can provide handiwork economically.”

Only three or four examples of the Z-102 were built before Pegaso came out with an upgraded model, the Z-102B, in 1951. While the core chassis remained essentially the same, the engine was now enlarged to 2.8-liters (2,816-cc) by taking the bore out to 80-mm and leaving the stroke the same at 70-mm. Power output for the 2.8 was raised to 170-hp, with 160-lb-ft of torque. However, should the enthusiast want even more performance there was also a 3.2-liter model (85-mm x 70-mm) that boosted output to 195-hp and 185-lb-ft of torque. Across all the engine displacements, Pegaso also offered a supercharging option that yielded 250-hp (2.8-liter) and 285-hp (3.2-liter) with single-stage supercharging, or one could opt for a two-stage supercharger on the 3.2-liter model that boosted its power to an astonishing 350-hp! In its 2.8-liter, supercharged form the Pegaso Z-102B was able to clock a flying kilometer speed of 151 mph on Belgium’s Jabekke Highway, making it the fastest production car in the world at that time.

From Jewels Back to Trucks

In 1956, Ricart had ideas of selling more Pegasos to the growing American market. Due to the expense of the dual overhead cam engine, Pegaso began developing a less expensive engine, now with a pushrod V-8 that could be had in 4.0-liter (247-hp), 4.5-liter (254-hp) or 4.7-liter (276-hp) displacements. This new engine was mated to a Touring 2+2 body and was dubbed the Z-103. However, only 3 examples were ever actually made as the new engine proved problematic and the car itself was really more of a “prestige” showpiece than a commercially viable automobile. By 1958, Ricart and Pegaso were faced with a problem. The truck and bus business had become very profitable, with high demand for Pegaso products in a number of European markets. But due to Pegaso’s lack of a mass production assembly line system, whenever one of the sports cars was to be built, truck production had to halt, while workers assembled the car! After having produced perhaps only 84 examples of the Z-102 and Z-103, the decision was made to halt production and focus on heavy trucks.

As soon as 1959, Ricart was exploring the idea of building a six-passenger Pegaso, but sadly the caballo volador (the flying horse) would never again grace the hood of another automobile.

The Panorámica

The story of the car you see on these pages (Chassis #72) is both fascinating and moving. Chassis #72 was built in 1956, but is in fact, one of the three rare Z-103 cars built for that year’s show circuit. One of the Z-103s remained in Barcelona where it received a body from Carrocerías Serra, while the other two examples (of which this is one) went to Touring to receive a Superleggera 2+2 coupé body. Unlike many of the other Touring-bodied Pegasos that featured a fairly flat windscreen, these two examples were given a more curved windscreen with less prominent A-pillars. As a result the cars were termed “Panorámica Coupés,” for their more panoramic windscreens.

Chassis #72 was placed on the stand at the April 1956 Turin Auto Show, where it was displayed with one side of its Borrani wire wheels removed to show its shiny painted DeDion rear end and independent suspension. The car next turned up on the Pegaso stand at that October’s Paris Salon. Subsequently, the car was sold to a resident of Bilbao, Spain, by the name of Florentino de Lecanda Arrire. While his ownership is well documented (the factory even installed a custom ID plate with his name inscribed on it), what isn’t well known is when exactly the rare pushrod 4-liter engine was removed and replaced with a 3.2-liter, 4-cam engine. Whether the engine was changed before Arrire purchased the car, or whether he returned it for replacement after purchase is unknown. However, the factory saw fit to reissue the chassis tag, which indicates a Z-103 chassis, mounted with a Z-102 engine, which might suggest that the engine was replaced, before the sale, otherwise why change the tag to reflect a different engine number after the fact?

From this point forward the Panorámica’s ownership trail goes cold until the early 1970s. In 1972, an 18-year-old, Southern California gearhead by the name of Jeff Vopal befriended a doctor who owned not only Chassis #72, but also a Saoutchik-bodied Coupé (Chassis #35). Vopal fell in love with the now down around the edges Pegasos and hounded the good doctor to sell him the cars. Eventually, the doctor agreed to sell Vopal and his father Jack both cars for the same amount he paid for them…$5,000!

The Vopals planned to restore the Pegasos as a father and son project, but soon Jeff went away to school, followed by a job out of Simi Valley, California where they lived, and so the Pegasos sat in storage. But in 1990, Jeff’s work brought him back to Southern California and he soon moved into a house just three miles from where his parents lived. The long awaited restoration could begin, with the ultimate goal being showing the cars at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, an annual pilgrimage that father and son had made together for over 20 years.

But soon thereafter, tragedy struck. Jeff was diagnosed with Lymphoma in March of 1992 and he would succumb to the illness a scant 6 months later, just shy of his 38th birthday. The Vopal family was devastated. So much so, that Jack couldn’t bring himself to make his annual trip to Pebble Beach—too many memories. But his daughter Cindy and her husband Karl Baker convinced Jack to go the following year in 1993, where they learned that the next year, one of the featured marques was going to be Pegaso. With only 50 weeks before the 1994 concours, Jack and Karl decided that they would restore one of the Pegasos as a tribute to Jeff.

In disassembling the car, Karl and Jack were surprised by the fact that one side of the car’s suspension appeared to be surprisingly well preserved and painted while the other side wasn’t. This fact and a conversation with someone who had actually been present at the 1956 Turin Show helped confirm that Chassis #72 was in fact one of the two show cars that year.

Over the coming weeks, Karl found himself needing to remanufacture more and more parts for the Panorámica. As a result, he and Jack ended up purchasing a local machine shop, which Karl still runs today. Finally, after weeks of painstaking work the Panorámica was finished in time for Pebble where it was judged Best in Class. Since then, the Panorámica has won over 100 awards, including another win at Pebble, Best of Show at Concorso Italiano, a class win at the Louis Vuitton in New York and Most Elegant Sports Car at Amelia Island. A fitting reward for all of Karl and Jack’s hard work and a stunning tribute to the life and memory of Jeff Vopal, the car crazy kid who made it all possible.

Driving the Panorámica

With some degree of anticipation I press the chrome dot on the driver side door of the Pegaso and an elegant chrome door lever sprouts from the car’s aluminum skin. Pulling the door open, I slide my right leg under the Nardi wood rimmed steering wheel and settle myself into the soft burgundy leather seats. For all of the Pegaso’s cutting edge ’50s technology, the luxurious interior does fall victim to the same set of bizarre ergonomic notions found in so many cars of this period. Italian cars from the ’50s are noted for having the pedals extremely close to the driver, while the steering wheel is quite far away. Conversely, British cars of this same time period, seem to always have the steering wheel right under the driver’s chin, but so much leg room that a basketball player could drive. Strangely, Pegaso somehow captured the extremes of each with both a close steering wheel and close pedals!

Despite having a little difficulty getting my 6-foot frame to conform to the Pegaso’s cockpit layout, the interior is richly appointed and nicely finished with the dashboard dominated by a large black binnacle with three oversized Jaeger gauges providing the necessary information (in Spanish) and a uniquely shaped Bakelite shift lever positioned just to hand.

To the left of the binnacle, I give the key a twist to turn on the ignition, flip up two toggle switches for the electric fuel pump and the magneto and then press my thumb down on the black starter button. The starter grinds away, releasing an ensemble of whirling and gnashing sounds from the engine compartment, but the engine doesn’t fire. Sitting next to me, Karl Baker, encourages me to give the accelerator a few more deep pumps and another try. After a few more seconds of whirling, the Pegaso’s V-8 slowly comes to life as it gradually clears its throat. Somewhat surprisingly the Pegaso’s V-8 has a fairly loud, raspy engine note, overlaid with the distinctive whirring and whining of the four gear-driven, overhead camshafts. The sound very much reminds me of a purpose-built racing engine, rather than what I would expect from a grand tourer.

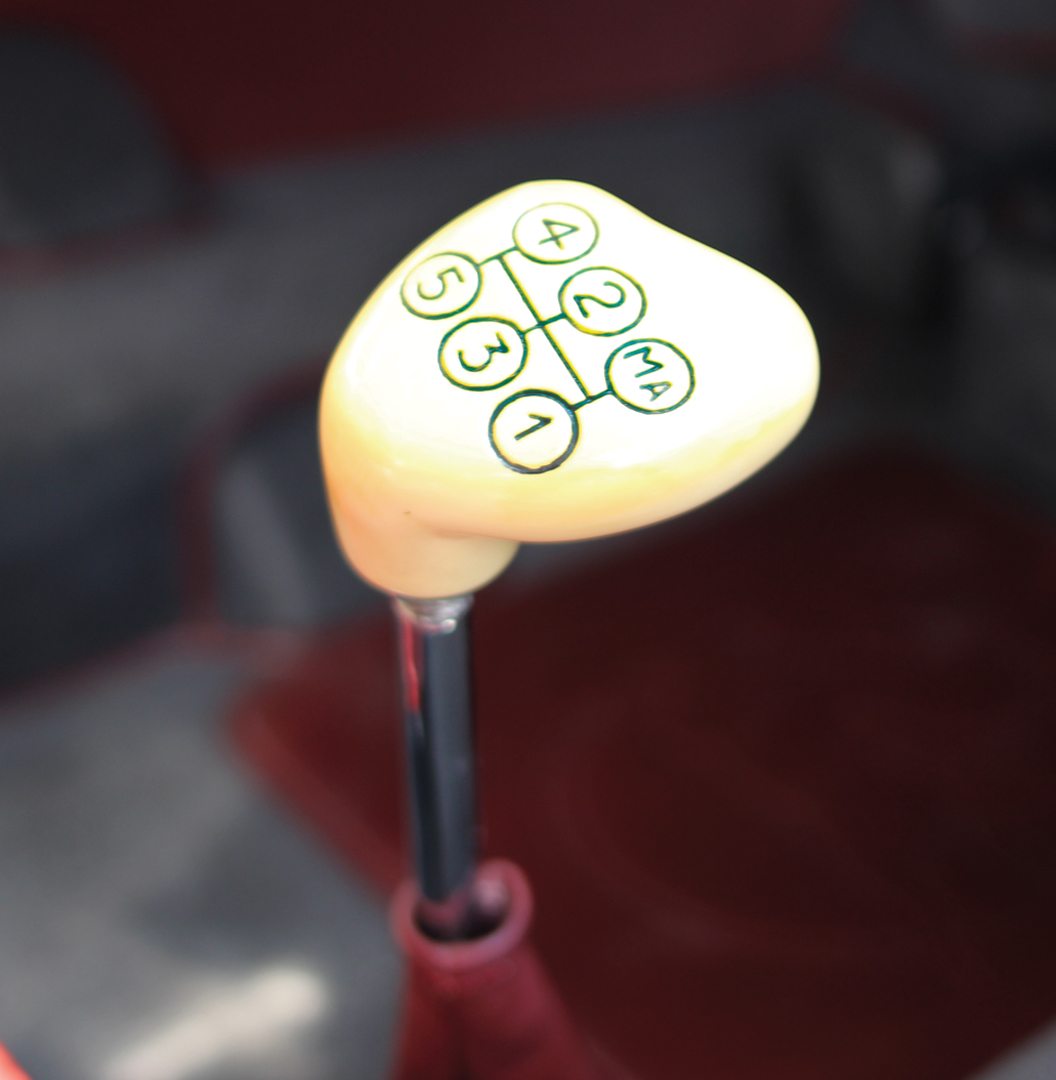

Grasping the strangely-shaped, ivory-colored gear shift lever, the pattern etched on the surface reminds me that the Pegaso’s shift pattern is reversed, with first over to the right and back, reverse forward of that, with second central and forward, third straight back and fourth and fifth back towards me. Due to its dogring-engaged gears, selecting first requires several attempts at dipping the heavy clutch and forcefully pulling back to try and engage the gear. After three such attempts I get the Pegaso in gear, feed in some gas from the vaguely communicative accelerator pedal, let out the clutch and the Panorámica pulls away.

Chugging along in first gear, the dominant sensation is that of whirling gears—gear train in the engine, and constant mesh in the transaxle—its a wonderfully purposeful collection of sounds that communicates to the driver that the car has something serious up its sleeve. With a further push of the right pedal the Pegaso unleashes a growl from the almost delicate set of four exhaust pipes at the rear and quickly yearns for an upshift. It’s in the shifting where things become counterintuitive. For anyone who has ever driven a purpose-built racecar with a dogring gearbox, you will know that these transmissions require a very firm, almost heavy hand when shifted. They don’t like slow, gentle shifts. Shifts must be quick and decisive. Of course, when driving someone else’s gorgeous 100 concours winning show car, one instinctively wants to be delicate and gentle! However, delicate and gentle is rewarded with graunching and grinding from the expensive Pegaso transaxle, so quick forceful shifts become the order of the day.

Out on the open road, the Pegaso feels ever more lively with increased speed. The engine doesn’t produce masses of torque, so it likes to be revved in order to make its power, which is fine, since the gearbox is at its happiest when being shifted quickly at higher rpms. Steering is quick and gets lighter with speed, though some of the looseness I detect in the linkage Karl informs me is due to a bushing that he never had the opportunity to replace. Stepping on the brake pedal, the Pegaso hauls down from speed very quickly. The massive vented drums do a very effective job of slowing the relatively heavy Pegaso down. Whether they would prove up to the rigors of extended and heavy use would be difficult to answer, though some contemporary reports did complain of eventual fade.

While the Panorámica is now seldom driven and suffers from a few of the peccadillos of a car that is not regularly exercised, overall when fully sorted, the Pegaso would be a fantastic car to take on high-speed runs through open, meandering roads, where the car could be given its full head of steam. While sold in period, as a luxurious tourer, the Pegaso would have been a difficult machine to live with in a urban environment where its relatively noisy, higher-revving engine and challenging gearbox would have made city driving exhausting work.

But then, that assumes that Ricart’s jewels were intended to be something more than the fabulous technological showpiece that they were.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis Steel platform

Wheelbase 91.5-in

Front Track 52-in

Rear Track 50.8-in

Weight 2350-lb

Suspension Front- independent wishbones, with torsion bars, Rear- DeDion with radius rods and torsion bars.

Engine All-alloy V-8, with twin overhead camshafts

Displacement 3.2-liter

Bore x Stroke 85-mm x 70-mm

Carburetion Twin Weber 4-barrel

Compression 11:1

Horsepower 195-hp

Torque 183-ft-lb @ 3500

Gearbox 5-speed, close ratio, constant mesh, dog ring transaxle

Brakes 12.8-in drum

SteeringWorm and sector