Quite simply, cars raced by Dick Seaman are few and far between. The British driver was active in our sport for only a handful of years, and for three of those he was employed as a factory driver for Mercedes-Benz. This alone makes it extremely difficult to “get your hands” on one of his machines. However, I will be forever thankful that an opportunity arose for me to sample one of his iconic racing machines for Vintage Racecar on a cold sunny February morning and fulfil an ambition to follow in the wheel tracks of my biggest racing hero…

SETTING THE SCENE

Richard John Beattie Seaman was born on February 4, 1913, and almost 100 years to the day I was handed the golden opportunity to drive one of his cars—the 1936 Aston Martin Speed Model, chassis H6/711/U. In this car Seaman contested the ’36 Tourist Trophy at the Ards circuit in Northern Ireland—a race he led until his 2-liter engine seized due to a lack of oil.

In the pre-war era Seaman was quite simply Britain’s finest racer. Starting his career with an outing at Shelsley Walsh in 1931, the determined young man quickly found success on the circuits with an MG Magnette during the 1934 season. For 1935, he switched to one of the new Bourne-built English Racing Automobile (ERA) cars. Driving R1B, painted black, Seaman scored victories at Pescara and Bremgarten in the Coppa Acerbo and Prix de Bern events.

While the ERA remained the weapon of choice for many, Seaman changed direction away from the marque and purchased a Delage for the 1936 season, winning multiple races with the car, while also taking in the TT with the Aston and winning the Donington Park Grand Prix with Hans Ruesch in a 3.8-liter Alfa Romeo, among others.

Photo: Mike Jiggle

Courted by Mercedes-Benz, Seaman was signed as a factory driver for the 1937 season—becoming a titan of the golden age in the process. In spite of the dark clouds gathering over Europe, the Englishman shone brightly in his “Silver Arrow” and displayed skills that rivalled those of other Mercedes-Benz drivers such as Rudi Caracciola, Hermann Lang and Manfred von Brauchitsch.

His finest hour was on a summer’s day at the Nürburgring, when driving a W154, he won the German Grand Prix. The German crowds cheered wildly for the popular Seaman, to the obvious embarrassment of the officers of the Nazi regime present at the circuit. Second at Bremgarten and a 3rd-place finish at Donington were other notable highlights.

Seaman found his on-track activities limited during 1939. A broken clutch ended his hopes of another success at the Nürburgring, his only outing of the season before Spa-Francorchamps and the Belgian Grand Prix.

On June 25 in torrential rain, Seaman was on top form. At the wheel of the #26 Mercedes-Benz W154 he was lapping quickly and leading the race. Pressing on in awful conditions, Seaman’s luck ran out and he spun at the Club Corner, the left-hander prior to La Source. The Mercedes-Benz was sent crashing into the trees, catching fire on impact. Trapped in the car, Seaman suffered horrific burns and was eventually extracted from the car and taken to the Croix Rouge Hospital in Spa. He was conscious, but in terrible pain. He told those by his bed that the accident had been his fault. He even apologized to his wife, Erica, and said he would now not be able to take her to the cinema that evening!

Later that night, Britain lost its finest racing driver, at an age of just 26. Seaman’s funeral was well attended. Practically the entire Mercedes-Benz team was present, including two directors from Daimler-Benz and team manager Alfred Neubauer, as well as representatives from the German Embassy. Colleagues from the British racing scene also paid their respects, while a six-foot wreath of white lillies tied with red moire ribbon delivered to the church simply carried the words “Adolf Hitler.”

The Royal Automobile Club Tourist Trophy has always been one of those races that everyone wants to win. Its roll of honor by 1936 was already long and distinguished, and its victory laurels were a prize that Aston Martin indeed wanted to possess.

The Ards circuit in Northern Ireland played host to the race at that time. Close to Belfast, the Ards track followed a fast triangular layout, with the Pathe News film of the period describing the course as the fastest within the British Isles. Running between Dundonald, Newtownards and Comber, the County Down track didn’t suffer fools gladly and thus demanded respect. Speeds were high and its nature left little room for error.

To win the Tourist Trophy Aston Martin had to work hard and they constructed a car they hoped would do the job. Built in their Experimental Shop, and sporting a body by E. Bertelli Limited, a Speed Model two-seater was produced to be driven by Dick Seaman. Hopes were high for the marque’s challenge in the race as the car was sent on its way across the Irish Sea to the docks at Belfast.

Photo: Andy Bell-Ecurie Bertelli Collection

The entry list for the TT was divided into classes depending on engine capacities, with the largest being for cars ranging from 3- to 5-liters, and so it was a typically diverse field. Bentleys and Lagondas could be found leading the list with TT regular E.R. Hall headlining the efforts for Bentley. Lord Howe, Brian Lewis and Pat Fairfield represented Lagonda, while in the 2-liter class, the Aston settled alongside a sister car entered by Doreen Evans. Two German BMW cars, one of which was driven by B.Bira, could also be found here, while Rileys largely made up the 1.5-liter class with Fiats and Singers rounding out the field in the smallest displacement category.

The Ards circuit was formed on closed public roads and measured about 14 miles in length. Practice runs could only take place during certain hours, on days prior to the race, so that the roads could be re-opened for the public to move about. Many competitors found that they had teething problems to sort with their racing machines, Aston Martin being one of them. The car had not enjoyed any run time before its departure to the peninsula, and so the first teething problem was when it failed to pick up its oil during practice and it consequently seized a piston. The offending item was replaced prior to the race, although concerns were raised as to the potential longevity of the car once the race was under way.

Photo: Andy Bell-Ecurie Bertelli Collection

Heavy rain greeted competitors on the morning of the race and for the first half of the event made for incredibly treacherous conditions. However, these were conditions that Seaman revelled in and thus allowed him to push on with a pace that didn’t put his doubtful engine under too much stress. As the race progressed, Seaman moved the Aston into contention. With huge plumes of spray following the cars around the track, Seaman settled down and broke the class lap record on a number of occasions until the Aston once more failed to feed itself sufficient oil and its engine seized. Seaman was out and a long walk back to the pits followed. His time behind the wheel of the little Aston was over.

THE CONTINENTAL SCENE

Rebuilt at the works following the TT, the car found its way to a new enthusiastic owner in the shape of Dutchman Eddy Hertzberger during the early months of 1937. Paying nearly £500 for the car, the Dutch industrialist had it colored from time-to-time in the Dutch national racing colors of orange and entered it for the Mille Miglia. The Aston retained its original number to facilitate customs documentation, although the car’s original engine made way, eventually finding itself into an Aston single-seater track car.

Hertzberger teamed up for the legendary Italian race with his mechanic, Jacques van der Pijl. Hertzberger insisted on meticulous preparation of the car, and the faithful van der Pijl was happy to oblige. He fitted an extra driving headlamp to the front and moulded it into the fairing. Internal fuses and switches were fitted to look after each light, to avoid any time being lost during night driving should the electrical circuits fail, and a second SU pump was fitted with a switch to bring this reserve unit into action should the primary pump fail.

The race was on April 5, and Hertzberger was in fine form with the car. Running as high as 4th overall at one point, the Aston settled into a steady 7th to 9th position having led the 2-liter class from Bologna to Siena. Only after Siena did things go against the Aston when the engine revved hard and a valve spring broke. Under a scorching sun, the spring was replaced and Hertzberger and van der Pijl were back on their way, although valuable time had been lost. Late in the evening, the car was still running 2nd in class but after some 13 hours behind the wheel fatigue took its toll and an approaching car with only one headlamp sent Hertzberger driving toward the ditch. The Aston plopped off of the road and it was only thanks to spectators that the car was able to be lifted back onto the road to allow its race to be completed. Egged on from the passenger seat by his friend, Hertzberger ensured the Aston completed the race, finishing 16th overall and 2nd in class. It was a fine result at the fall of the checkered flag.

Photo: James Beckett Collection

For the Le Mans 24 Hour race, Hertzberger was joined by French racer Albert Debille. This was a partnership that would share several adventures in the Aston, although at the Circuit de la Sarthe things did not go their way and they were forced to retire after 136 laps with engine failure. The race was won by the Bugatti of heroic French drivers Jean-Pierre Wimille and Robert Benoist, much to the delight of the huge crowds watching from the tribunes. Victories did follow for the Aston though. Debille took a win in the Montlhéry Speed Cup, as did Hertzberger in both the Belgian Grand Prix des Frontieres and the A.G.A.C.I. Grand Prix run by the French Drivers Association.

For 1938 the car was again entered into the Mille Miglia, where Debille became a late replacement to share with Hertzberger after van der Pijl switched to the Talbot driven by Carriere. Van der Pijl had lovingly carried out all the pre-race preparation on the Aston, and so it was ironic that he went on to finish 2nd overall in the Talbot while the Aston retired with engine failure. The car did score one final victory in Hertzberger’s hands though, claiming the Coupe des Paris in a 20-lap race around the 3.33-kilometer Montlhéry short circuit. The Dutchman’s final race in the car was on a street circuit in the St. Anneken event near Antwerp in Belgium. In this race, the BMW 328s were formidable opponents to the Aston, as always, and in trying to beat them Hertzberger over-revved the engine and a rod broke. Hertzberger also called a halt to his racing career—and gave up up on his marriage!—in late 1938. The car was subsequently rebuilt and sold back to England from Rotterdam through the Aston Martin dealer and was not seen again until after hostilities had finished at the end of the Second World War.

Photo: Andy Bell-Ecurie Bertelli Collection

INTERNATIONAL CHALLENGES CONTINUE

A quick blast along the Brighton seafront, during the Brighton Speed Trials of 1946 with Mrs. Elwes at the wheel, put H6/711/U back on the map, and by 1948 the international world of motorsport was once more, spreading its wings as the horrors of WWII began fading into memory.

The Aston again headed for mainland Europe where its first stop was in the Ardennes for the Spa 24-Hour Race. Now known as “Red Dragon” (Registration FGY 409) and prepared and rebuilt by John Wyer at Monaco Garage, the car was driven by Dudley Folland, a man famous for importing the first Ferrari into Great Britain. The Welshman would be joined by Ian Connell. The pairing was joined on the grid by another Aston Martin Speed Model driven by St. John “Jock” Horsfall and Leslie Johnson. In typical Spa weather, the race ran in torrential rain. Huge clouds of fog also hung over the wooded circuit, making racing conditions some of the worst ever seen at the venue. The cars pressed on, however, and as the race progressed the track became littered with the remains of cars that had crashed off the road. One such car was our Aston. Running 2nd overall, Connell skidded on the wet track and, looping round twice, slid from the track and into a roadside ditch. Connell escaped uninjured, as did the car—its engine still capable of running. However, the state of the ditch meant that the car could not make it back to the track, and so its race was run. It might not have been our car’s day, but Aston did win, with Horsfall and Johnson driving their #54 machine to victory.

Photo: Andy Bell-Ecurie Bertelli Collection

Just under two months later, Folland and Connell were back in action, this time in the A.G.A.C.I.-administered 12 Heures du Paris at Montlhéry. The duo enjoyed some luck, with John Wyer again running the team from the pits. After a spirited drive they scored a very satisfying 3rd overall, 2nd in class.

For 1949 the car once again headed to Le Mans to take part in the world famous Grand Prix d’Endurance where numerous Aston Martins were entered to compete. The “works” cars were managed by John Eason Gibson, while “Red Dragon” was to be looked after again in France by Wyer, with Folland joined at the wheel by Anthony Heal. The race was short-lived for our Aston when the Speed Model lost its ignition control. The inevitable holed piston soon followed. After Le Mans the car traveled to Spa for the 24-Hour Race, an event that would be remembered for Jock Horsfall’s incredible solo drive for the entire duration of the race in the “Spa Special” Speed Model. The Red Dragon was again driven by Folland and Heal, but exited the proceedings on lap 142 with a broken track rod when lying 3rd in the 2-liter class.

HOME SERVICE

By the turn of the decade Red Dragon was beginning to show its age on the international scene and, as it did for many such cars a career in national racing was beckoning. In 1952, the car enjoyed a run out at Silverstone where it finished 3rd, while it also won a handicap event at Goodwood in the hands of Jack Fairman. Sporadic outings continued through the 1950s, before the car became settled with the Bishop family starting in 1960. Geoff Bishop became a regular in Aston Martin Owners’ Club events with the car, winning races and sprints at Silverstone, Wiscombe and Curborough. Additional outings at Brands Hatch, Crystal Palace, Oulton Park and Prescott also featured before the car disappeared from active service for a lengthy period before reappearing again in the summer of 1989, with Geoff Bishop once again at the wheel. The partnership enjoyed their first race action again after an absence of 17 years, once again thrilling spectators who instantly recognized the now famous car.

Red Dragon is still a regular on the race circuits of Britain and Europe today. The car, I believe, has one of the most impressive histories of any machine to carry the famous Aston badge, and is certainly one of the most significant Aston Martin cars of all-time. It is as happy racing around the streets of Monte Carlo and Pau, contesting the Mille Miglia, roaring down the Mulsanne Straight at Classic Le Mans or taking part in national events, as it ever has been. This car is a racer, it always has been and it always will be.

FOLLOWING IN “THOSE” WHEEL TRACKS

Walking toward Red Dragon I must admit I felt the hand of history on my shoulder, somehow guiding me, steering me, in the right direction. As I said earlier, Dick Seaman is my all-time racing hero and I felt a huge responsibility climbing over the side of “his” Aston and lowering myself into the cockpit behind the huge steering wheel and preparing myself to follow in “his” wheel tracks.

It didn’t take long though to feel comfortable and right at home in the car. A quick wriggle into the comfortable, but basic, leather trimmed seat and a check of the mirrors was really all it took and I was ready for the off! My stretched-out legs easily located the pedals and with a winter sun shining on my back I reached for the ignition switches and button to fire the car into life.

Starting the Aston required a flick of three switches, all banded together for ease, and a press of a starting button. The engine barked immediately and it didn’t require any throttle to keep it ticking over. However, the sound of the car’s two-liter engine was so good I couldn’t resist a blip or three of the throttle to hear the sound of its exhaust as it exited along the side of the car behind me.

Sitting in the Aston the gear lever was well positioned. I didn’t need to stretch to find first gear. A well-machined gate allowed me to push the lever directly into first and as I let out the clutch Red Dragon rolled forward. Quickly picking up speed, I took second gear almost straight away as my weight on the throttle had caused the car to judder. A dear friend of mine advised me that if that happened I should change up instantly and this would eliminate this kind of trouble in a car of this age. He was right. I could hear his advice in my head as I also moved from second to third.

At slow speed the car displayed great torque and pulled readily. It seemed more than happy on the small winding British roads of Northamptonshire and Buckinghamshire, but I can imagine it would also feel pretty happy at high speed in the Ardennes, at Le Mans or around Ards! As I drove along I noticed how incredibly responsive the two-liter unit was and how it drove like a true racecar, not a road car. This car has undergone much preparation work for the track over the years, and this I believe has been a true benefit to how it performs today. This car has always been a racer and it felt like it. The steering was smooth and direct, the car didn’t want to dive away to the left or right, even on a British “A” road, and under acceleration out of tight corners the traction was, I must say, enjoyable.

Picking up speed and moving into top gear (fourth) the Aston sang loudly as it continued to accelerate. With its current gearing I was told that the car would be more than capable of over 130 mph on the Mulsanne at Le Mans—exciting stuff—especially in the 1930s!

Catching the eye, the car’s dashboard glinted beautifully in the morning sunshine and the chrome from the mirrors and window surround added grace and beauty to go with the racy look that it inherited courtesy of John Wyer back in the late 1940s, a little wolf in sheep’s clothing. The little car—and I call it that because when I was driving along it did feel small and compact—was a real thrill and an absolute delight to drive, in my mind things don’t get much better than this, and numerous pre-war cars I have driven simply do not compare.

SPECIFICATIONS

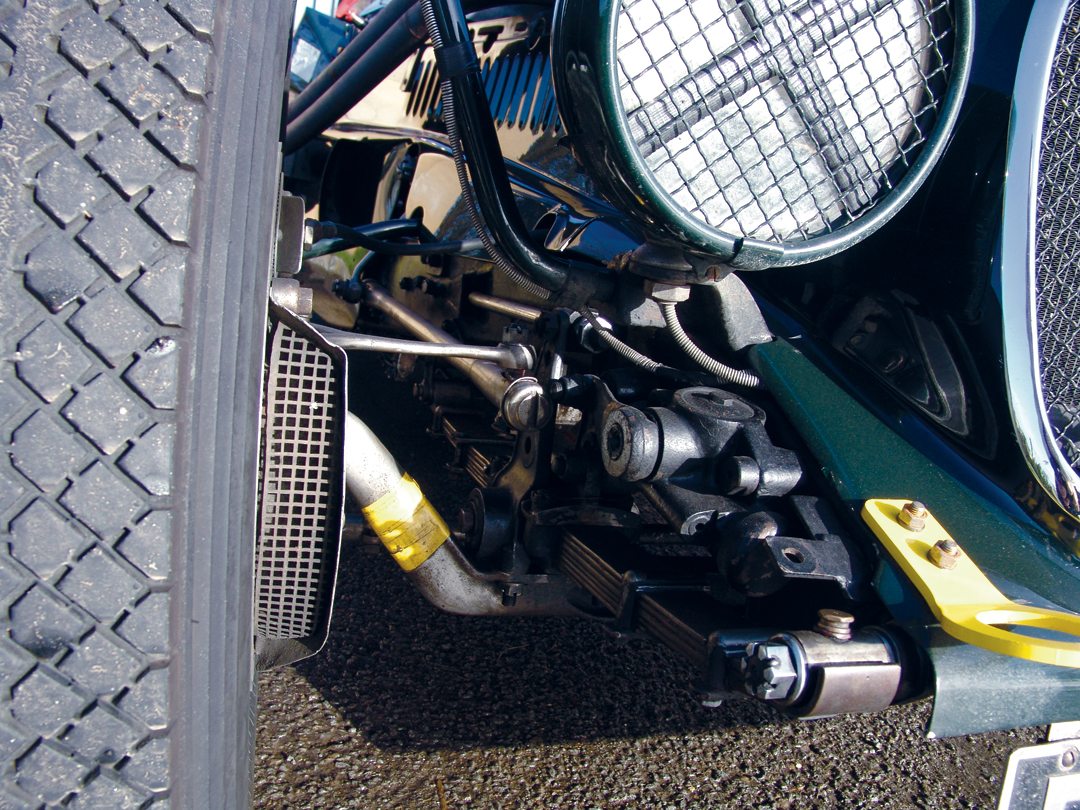

Chassis: Steel channel with four channel section crossmembers and round section cross tubes to take chassis pins at front and rear

Wheelbase: 8 feet, 6 inches

Track: 4 feet, 6-1/2 inches, F+R

Suspension: H-section beam front axle and solid rear axle, semi-eliptic leaf springs with hydraulic shocks front and rear

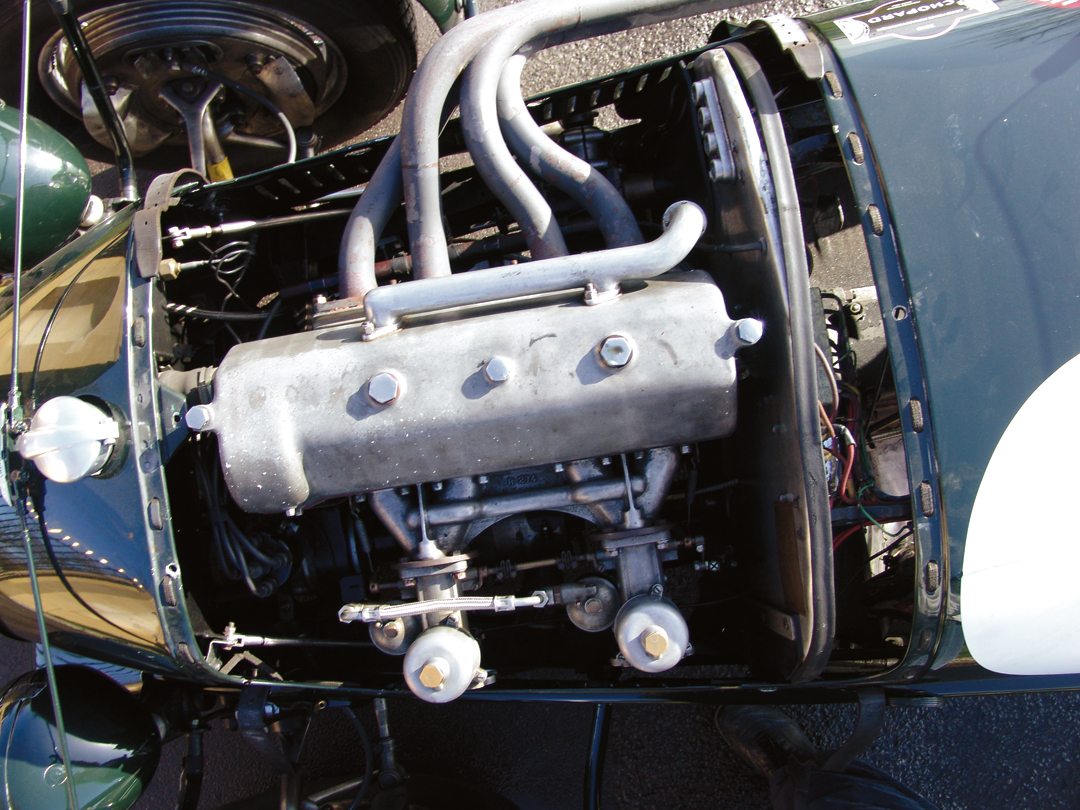

Engine: Overhead cam, 4 valves per cylinder; Electron replaces all aluminum castings to works racing spec

Displacement: 1950-cc

Bore x Stroke: 78-mm x 102-mm

Induction: Twin 1 3/4-inch SU carburetors

Power: Approximately 120 bhp

Transmission: Close-ratio, straight-cut 4-speed with Electron casing

Differential: ENV

Brakes: 14-inch hydraulic drum brakes

Wheels: 18 x 4-1/2 steel wellbase wire wheels with 52-mm hubs

Tires: 550/600 Dunlop racing tires

Acknowledgements / Resources

The author would like to thank Andy Bell of Ecurie Bertelli for his kindness and support in the preparation of this article, in particular allowing me to drive Red Dragon. My thanks also go to John Pearson for his words of wisdom prior to me driving, and during the test of, the car. His knowledge of cars from this period is second to none and I really can’t thank him enough for the continued support he gives me for my endeavours.

The archive of Ecurie Bertelli and Andy Bell

The AMOC Register of Members’ Cars

The AM Magazine

Shooting Star – The Life of Richard Seaman by Chris Nixon

Aston Martin The Story of a Sports Car compiled by Dudley Coram

Speed Magazine

Road Racing 1936 by Prince Chula

Aston Martin and Lagonda by Michael Frostick