The UK’s Celtic county of Cornwall is a land full of mystical fables and folklore of piskies, giants and mermaids, together with dramatically true stories of smuggling and pirates. It is situated on the southwest tip of England and has a coastline of around 445 miles. On the northern Cornish coastline just 37 miles northeast of Lands End, the most westerly tip of England, is the tiny seaside village of Perranporth. With the Celtic Sea and the Atlantic Ocean as neighbors, Cornwall is noted for seafaring industries, including fishing and boatbuilding. Mining for tin, copper, zinc and other metals was another industry synonymous with the county for many years. This mining industry was also responsible for a famous local pastry, the Cornish pasty. What has this got to do with our car? Well, Perranporth is the birthplace of Donald Mitchell Healey. Which begs the question, how did Donald Healey become a constructor of cars when he was born and grew up so far from the epicenter of the motor industry?

Photo: Pete Austin

Healey’s beginnings

Healey was the elder son of Frederick and Emma Healey, who ran The Red House Shop, a general store, in the village. The young Donald became interested in aviation. The fascination of flight for those growing up in the early 20th Century was very similar to those youngsters curious about space travel growing up in the mid-1950s and 1960s. It was a frontier man was yet to conquer in Healey’s era. Time and history now reveals how, mainly due to the World Wars, flight technology grew so fast. Today, we fail to be marvelled by it. Donald Healey, or DMH as he preferred to be known, was captivated by aircraft development. His parents—in particular his father, an avid motorist—encouraged him and after he’d studied engineering at Newquay College, he paid for his apprenticeship with the Sopwith Aviation Company at Brooklands. In 1916, prior to completing his apprenticeship, DMH volunteered to join the Royal Flying Corps and flew several missions before a crash invalided him out of the service. Continuing his studies in automotive engineering, at home in Perranporth, his interest was now diverted to motorcars, opening his first garage in his home village in 1920. While the garage was used to service and repair customer cars and as a base for his car hire business, there was still a burning spirit of adventure running through DMH’s veins. Motor racing and rallying consumed his mind from then on and his garage became his race preparation center. His first forays into rallying were with cars like the ABC, Ariel and Triumph Seven, entered into local events.

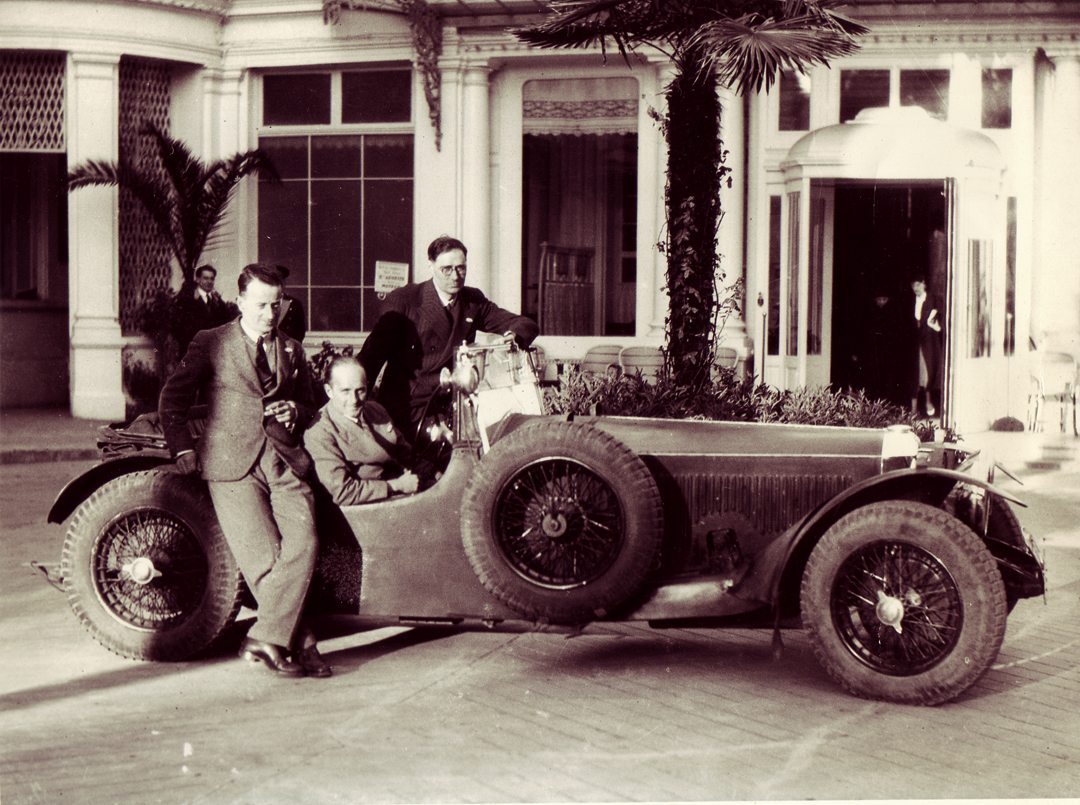

A first major event for the young English rally driver was the 1929 Monte Carlo Rally driving a Triumph Seven, finishing 7th—a creditable debut. An invitation from Sir Noel Macklin (Lance Macklin’s father) saw DMH join the works Invicta team, in 1930. Just two years after his debut, he won the 1931 Monte at the wheel of a 4.5-liter Invicta. His success continued in the event when he was the runner-up the following year. Victories in The Coupes des Alpes and three successive Alpine Trials didn’t go unnoticed by other manufacturers. Following the liquidation of Invicta, he sold his Perranporth garage and moved first to Riley and then Triumph, who were both based at Coventry in the Midlands of England—at that time, the heart of the British motor industry. It was Triumph that offered him the opportunity of exploring ways to engineer a proper works rally car by making him manager of their experimental department. Healey’s Monte Carlo Rally success continued in 1934 with a class win and 3rd overall placing driving his own design of the Triumph Gloria Monte Carlo. As the war years loomed, Triumph was in serious financial trouble, finally closing its doors in 1939. Healey arranged the sale of Triumph to Thomas Ward. In his time with Triumph, DMH had designed the Gloria roadsters and sedans and the Dolomite, a very advanced two-seater sports car powered by a twin-overhead-camshaft, 2-liter supercharged engine, based on the Alfa-Romeo 8C 2300…some would say a virtual copy, but much cheaper! Other versions of the Dolomite were powered by four- and six-cylinder engines.

In late 1939, the Triumph premises were taken over by the Air Ministry, in the form of H. M. Hobson, to assist the war effort and so DMH now turned to designing and building carburetors for aircraft engines, while always dreaming of one day becoming a constructor of his own sports car. Part way through the war years, DMH moved to Humber, again in Coventry, and worked on advanced armored vehicles. It was there that he developed a friendship with a fine mechanical engineer, A. C. “Sammy” Sampietro, formerly of Thompson & Taylor of Brooklands, and Ben Bowden, a talented body stylist. Between them they worked on a car design—taking a step closer to DMH’s ultimate dream.

Photo: Pete Austin

First Healey production car

Taking a small factory unit on an industrial estate in Warwick, all previous dreams became reality as the first car was produced, the Healey Elliott (Elliott of Reading producing the aluminum bodywork). The design of this new car was very advanced in relation to other vehicles of the day and, with power from a 4-cylinder, 2.5-liter Riley engine through a four-speed Riley gearbox, it achieved a top speed of 105 mph, becoming the fastest British production closed sedan—a record it would hold for some years. The Healey workforce amounted to some 50 staff producing around five cars per week.

The next design was a failed attempt; it amounted to a re-bodied Sportmobile version of the original car. However, the next model was more popular, the two-seater Healey Silverstone. Unfortunately, after initial success on both sides of the Atlantic, the Jaguar XK120 stole the thunder of the Healey together with sales in both the U.S. and UK markets. The Healey Silverstone had a good presence on the racetrack, especially in club racing, with drivers of the era coming to the fore at the wheel of the car, including a certain Tony Brooks.

Photo: Pete Austin

New Healey cars came into production as DMH forged associations with other manufacturing companies, including Tickford, which re-bodied the sedan and Abbott, who bodied the drop-head models. An association with Nash saw a new three-seater sports car, the Nash-Healey, with a massive 3.8-liter power unit by Nash and built, in the main, for the U.S. market. The first prototype model of this 125 bhp car, the X5, built on a modified Healey Silverstone chassis, was entered in the 1950 Le Mans 24 Hours driven by Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton to a very encouraging 4th place. Had it not been for Henri Louveau’s errant Delage ramming the Healey on the Sunday morning and delaying progress for 45 minutes, the car may have had a chance of catching the dominant Talbots. The U.S.-based Nash-Kelvinator Company looked upon this as a success and commissioned the build of replica models for the American market. The Healey works thrived with this order; success on the track had paid dividends and confirmed the adage “win on Sunday, sell on Monday.” The British market demanded a similar car from Healey and a few Alvis-powered models were made, but at over £2,000 each, customers considered them too expensive.

Birth of the Austin-Healey 100

Leslie Johnson and Tommy Wisdom had fared well racing the Nash-Healey to a 7th in the 1952 Mille Miglia and 3rd in the Le Mans 24 Hours. DMH knew he had to regain a footing in the UK market and needed a model to capture their imagination. At the 1952 London Motor Show, he unveiled a sleek new two-seater sports car with flowing body lines and powered by a 4-cylinder, Austin A90 engine. Named simply as the Healey Hundred it was an instant success, but Healey soon realized his factory could never cope with the volume and production of so many cars. Sir Leonard Lord of the Austin Motor Company, noted for the modernization of UK car manufacture, witnessed the clamor and interest for this new car. Lord came to Healey’s rescue by offering a partnership where Austin would produce the cars and pay Healey a royalty for each and every car made. Production by the Austin Motor Company couldn’t start until mid-1953, so Healey produced the first 20 at Warwick, after which they would be free to work on experimental models of the car at the factory that was still “flat out” producing the Nash-Healey for export to the U.S.

Here lies the headache for all of you keen on chassis numbers, Geoffrey Healey mentions in his book, The Specials, that the chassis numbers of these 20 cars have caused much confusion. The numbers issued by Austin ranged from 133234 to 134379, but with many gaps in between—the difference between the numbers being 1145. Austin production models started with the 21st car having chassis number 138031.

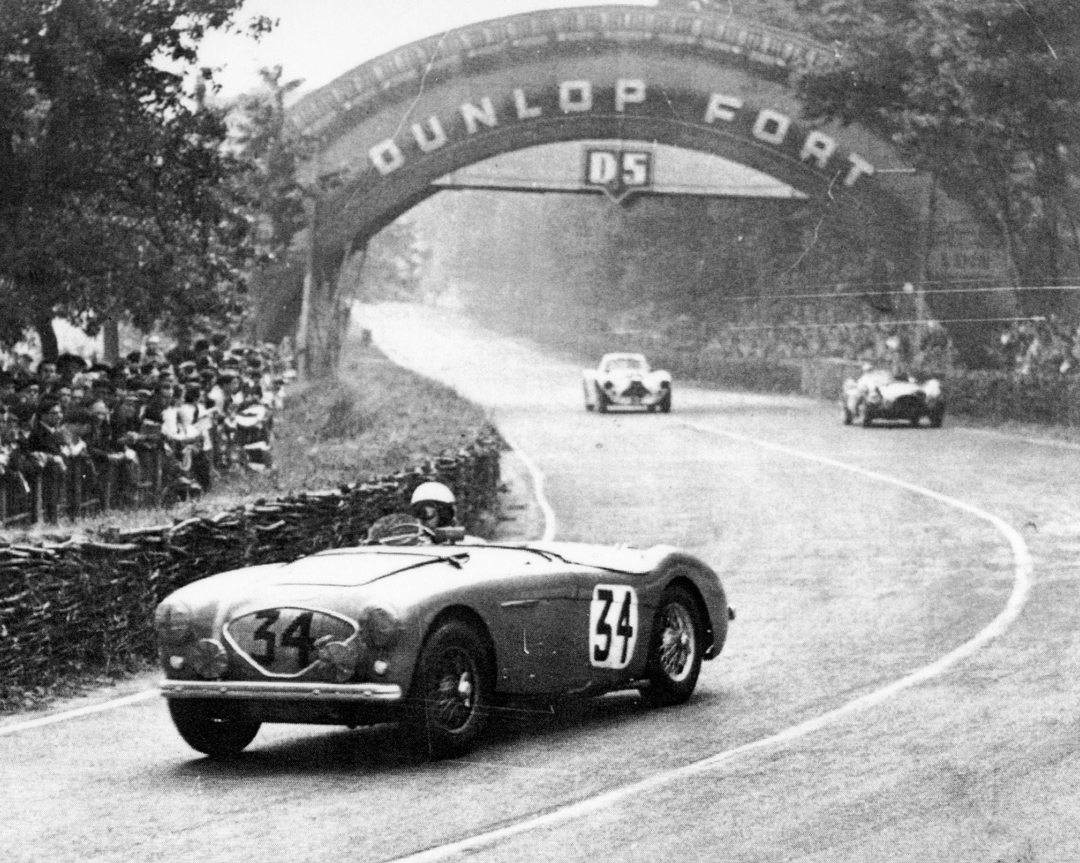

On the competition side, two near-standard cars were entered in the 1953 Le Mans 24 Hours, the most successful driven by Norton’s works motorcycle racer Johnny Lockett and his co-driver, Dutchman Maurice Gatsonides (famous inventor of the speed camera) who finished 12th, some 50 laps behind the winners (Healey’s former driving duo of Rolt and Hamilton who were at the wheel of a C-Type Jaguar.) Marcel Becquart and The Autocar’s Gordon Wilkins drove the second Healey. It finished 14th, not too bad for a first time out in the prestigious race. In DMH’s eyes, competition was key to sales. However, this competition wasn’t just racing. After talking with Captain George Eyston, holder of several land speed records and director of The Wakefield Oil Company (famous for producing Castrol Oil), DMH accepted the notion that speed records, especially in the U.S., would be ideal publicity for the new Austin-Healey 100. The ideal venue was the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah.

Photo: BRDC Archive

Record breaking at Bonneville

Capt. George Eyston was very friendly with the Mayor of Salt Lake City, David Abbott “Ab” Jenkins, who established land speed record breaking on the Bonneville Salt Flats, himself holding many records in the famous Duesenberg “Mormon Meteor.” After a meeting between Austin’s Len Lord, DMH and Eyston, a special test car (the fourth of such cars, SPL227/B) was prepared for the record attempt in Class D. The car was never road registered, although occasionally was seen bearing the plate NOJ 391. Eyston’s philosophy on record breaking was similar to the Ukrainian-born Olympic pole vault champion Sergey Bubka, who years later would see the value in only beating his record by the tiniest of differences so he could get publicity again and again for record attempts. Publicity was king if the Austin-Healey was to become popular on both sides of the Atlantic. Eyston obviously brought masses of land speed record experience to the table. One of his observations was the surface of the salt flats and the possible seizure of the steering due to the ingress of salt into the mechanism. Girling assisted by adopting their Luvax Bijur chassis lubricating system that was operated by the clutch pedal, whereby a small amount of Castrol EP140 gear oil would be pumped into the top and bottom of the swivel axle bearings each time the pedal was depressed. Few alterations were made to the car other than the use of the four-port Weslake engines designed by Don Hawley, one of Austin’s engineers based at the company’s Longbridge works, in Birmingham, England. The power of the engine was 131.5 bhp at 4,750 rpm on a 9 to 1 compression ratio. Harry Weslake designed the cylinder heads, moving the inlet and outlet ports from the left to the right side; therefore the exhaust pipe was on the right rather than the left so as not to restrict the number or size of the ports. Drive was through an Austin Taxi gearbox fitted with overdrive. The car was made as a left-hand drive, so as to keep the driver away from the hot exhaust. Much was done in the cooling department as experience showed that 90°F was “normal” ambient temperature for the driver. A cooling duct was directed at the battery to prevent it from boiling dry. The fuel tank needed to give a good three hours of running at 125 mph for the endurance record and was fitted with a quick-action filler cap situated on the boot of the car. In case of failure, two SU LCS carburetors were fitted. Of course, all unnecessary weight was taken out of the car.

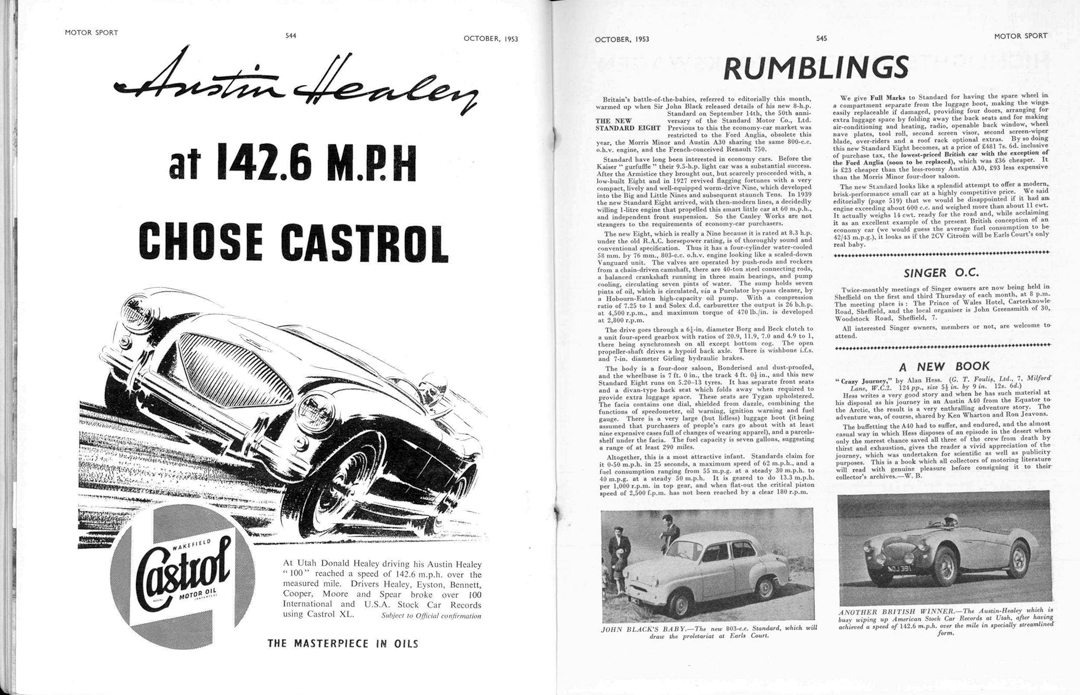

Donald Healey’s son Geoffrey, who had been with the company since leaving Armstrong Siddeley Motors in 1949, took the car out for its first run and systems test around public roads near to the factory. RAF Gaydon, a former Operational Training Unit in WWII, was chosen as the official “test track,” with high-speed runs falling in the hands of both Healey senior and junior. It proved successful and the car deemed fit for purpose to take on the challenges set before it. At this point, it was the fastest of all the Austin-Healey cars—by a country mile. The curb weight was 1,850 pounds and the engine gave 130 bhp. Over the 3,000-yard RAF Gaydon runway a top speed of 120 mph was achieved… without flooring the pedal! After this terrific performance, the car was freighted off to the Southampton docks, travelling via Cunard line to New York and then onto Utah’s salt flats at Bonneville. At 4,228-feet above sea level, the salt flats are considered one of the Wonders of the World. After preparation, including lowering the rake of the windscreen, highly polishing the bodywork and spraying the underside of the car with special oil for protection from the salt spray, the car set off for the start line. DMH did a first run, timed by the Southern California Timing Association (SCTA) at 131.81 mph—slower than anticipated. On a further run on September 9, 1953, DMH was officially timed at 142.55 mph after a kilometer and 142.64 mph after the full mile. The team was jubilant and the publicity process began. An engine blow and the onset of inclement weather thwarted an attempt on the endurance records, however.

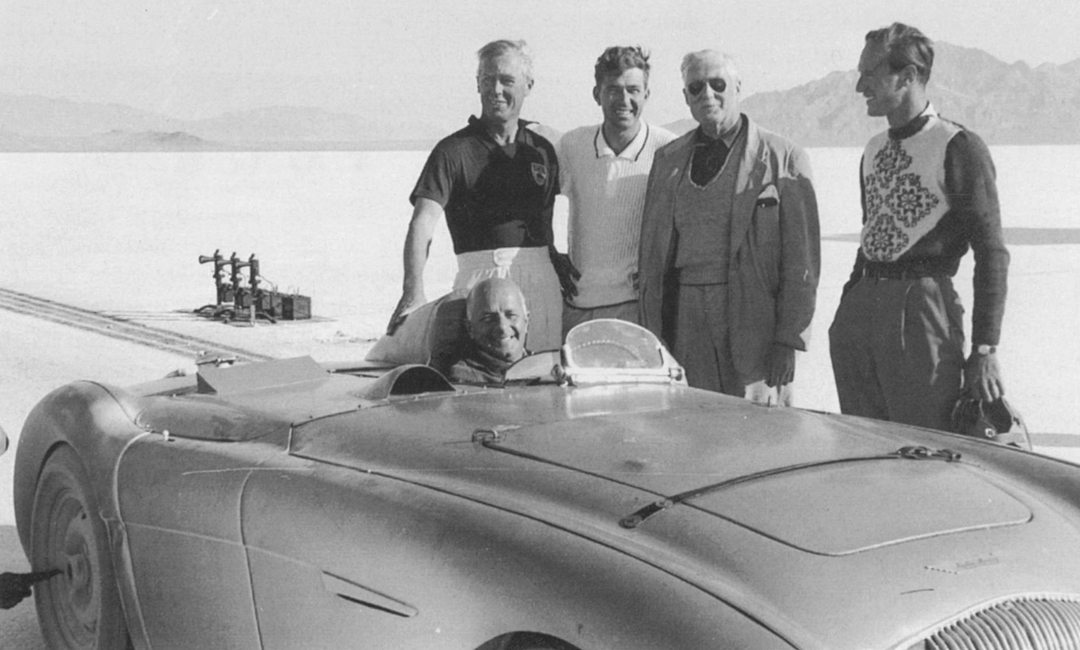

Photo: Simon Lewis Transport Books

After an extremely busy 12-month period in the experimental works at Warwick preparing cars for both competition and endurance, the Healey team returned to Bonneville almost a year later, in August 1954. This time they had a new streamlined car to go for the outright Class D Land Speed Record and SPL 227B returned to try and claim the endurance records. Following the success of the Healey Streamliner setting a record 192.62 mph, the next days were consumed trying to set many other Class D endurance records. The interim months had seen a painstaking rebuild and modifications made to the 1953 car in readiness for the 1954 record attempt. In a meticulous effort to save as many pounds as possible, revisions included the replacement of the original wraparound windscreen by a small aero screen, fitting new smaller lightweight disc brake units with 16-inch peg drive, light alloy wheels and a BN2 gearbox was fitted, minus the overdrive that was removed thanks to the use of higher axle ratios (this eliminated a slight power loss too.) The engine had also been tuned to give an extra 10 hp at around 4,500 rpm. Drivers for the endurance record attempt were DMH, George Eyston, Carroll Shelby, Mortimer “Mort” Morris-Goodall (founder of the Aston Martin Owners’ Club in the UK) and Roy Jackson Moore (a former RAF Mosquito pilot).

A routine shift system for driving was planned with stops every three hours to coincide with refuelling breaks. DMH would take the first stint, followed by Eyston, Shelby, Morris-Goodall and Moore. The evening through to the early morning would be the most troublesome period, due to the falling temperatures and the surface becoming very slippery. However, the car ran successfully for 24 hours, averaging 132.29 mph and bagging 83 National and International Class D records.

So, fait accompli, and sales soared in response. While successful competition results had the desired effect on car sales, interest in land speed records seemed to subside in the following years. Certainly it was the end of the road for chassis SPL227B. In 1957, despite the lengths the team went to in trying to protect the car against severe salt corrosion, the theory didn’t match reality and the car eventually succumbed to rust; useful parts were stripped and the car was subsequently cut up and scrapped.

Recreating a Record Car

In these days, we are used to the terms replica, continuation and recreation when a successful vehicle, no longer available, is reproduced. Even using the most authentic components, we will never see the original vehicle again in our midst. So, when Healey enthusiast Martyn Corfield looked at re-building one of the original 100/4 Special Test Cars, he turned to a company steeped in the history, heritage and tradition of the Healey marque—Denis Welch Motorsport. Construction of the car first started over the winter months of 2007/’08 using a donor car, chassis number 150943. Corfield explains, “I heard a rumor of ‘the last known factory chassis built to lightweight specification,’ which I purchased after verifying its likely originality with two known Healey specialists. This chassis is lightened in the ways that the works used and was being used in the ’70s to underpin another project. This seemed the best place to start a recreation.”

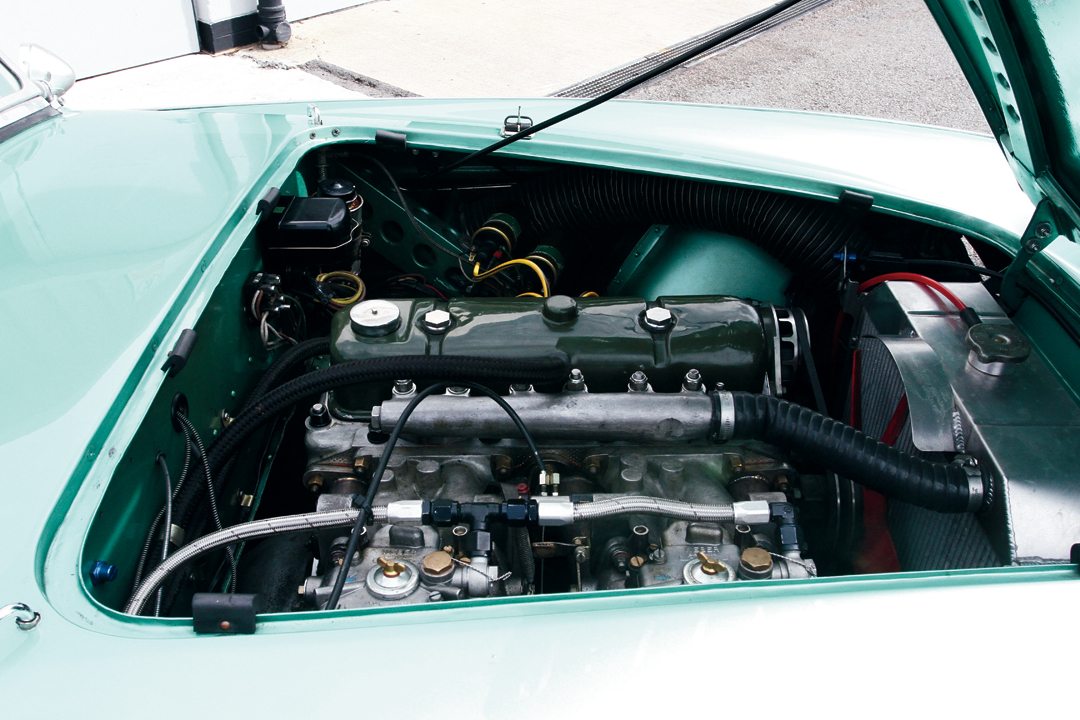

The objective of the exercise was not only to replicate the 1954 car, but also to construct a car to embrace period thinking, design and construction without any modern gimmicks and one that could be capable of setting speed and endurance records in its own right. Jeremy Welch headed the design and build team and the car was completed by May 2008 and readied for a “red letter day” at the Denis Welch Motorsport works. Former driver of the 1954 record car, Roy Jackson Moore, visited to give his appraisal of the new car. Roy had also been the North American sales Director for the Healey works, so his input was essential to ensure this car was as authentic as possible to the original model. His driving stint concluded the record attempt—it was he who drove the original car across the line and into the record books. After close scrutiny, he congratulated the team on such great work confirming that the tonneau cover and head fairing were in proportion to how he remembered them. The metallic green paint finish was as the original car, but the finish on the new car far outweighed the original as the original car was finished in such a great hurry. He was also able to lay a few fallacies to rest that had come into the build equation. There had been a suggestion that a David Brown gearbox had been used, Moore confirmed a BN2 ’box was used, as the DB gearbox was “horrible and needed two hands to change gear”—no good for attempting records! Small details, such as the use of the two-piece instrument binnacle were confirmed too. The team felt Moore’s comments and appraisal as invaluable—so far, so good!

The first appearance at a racetrack was the launch at Goodwood on May 16, 2008, just nine days after Roy Jackson Moore’s factory visit. Just as the period car was subjected to testing prior to the record attempt, this car was taken to the former RAF base at Bruntingthorpe in Leicestershire. Although once owned by Chrysler, the aerodrome is now a privately owned proving ground. The wide former runway sections of the track are ideal for high-speed testing. General Motors’ purpose-built proving ground at Millbrook in Bedfordshire, venue for the record attempt, was also used. These early tests showed the car capable of reaching the desired speed (147.2 mph) in a straight line at Bruntingthorpe, but the banked oval testing at Millbrook was disappointing—almost 10 mph slower. The thinking was that the tight radius of the Millbrook track was scrubbing off speed, so changes had to be made to accommodate this loss. While the original records at Bonneville were on a 10-mile radius oval, the Millbrook oval has a total track length of just two miles. Modifications were made to suspension settings and a less restrictive exhaust was fitted. A genuine factory works-style undertray was also used, and tested in the wind tunnel at the Motor Industry Research Establishment at Lindley, Warwickshire. The car was found to have some 1200 kilograms of aerodynamic lift, given that the car’s dry weight is just over 850 kilograms, it could have spelled disaster from the outset. Now reconfigured, all was set to try again at Millbrook to check if all the hard work had paid off.

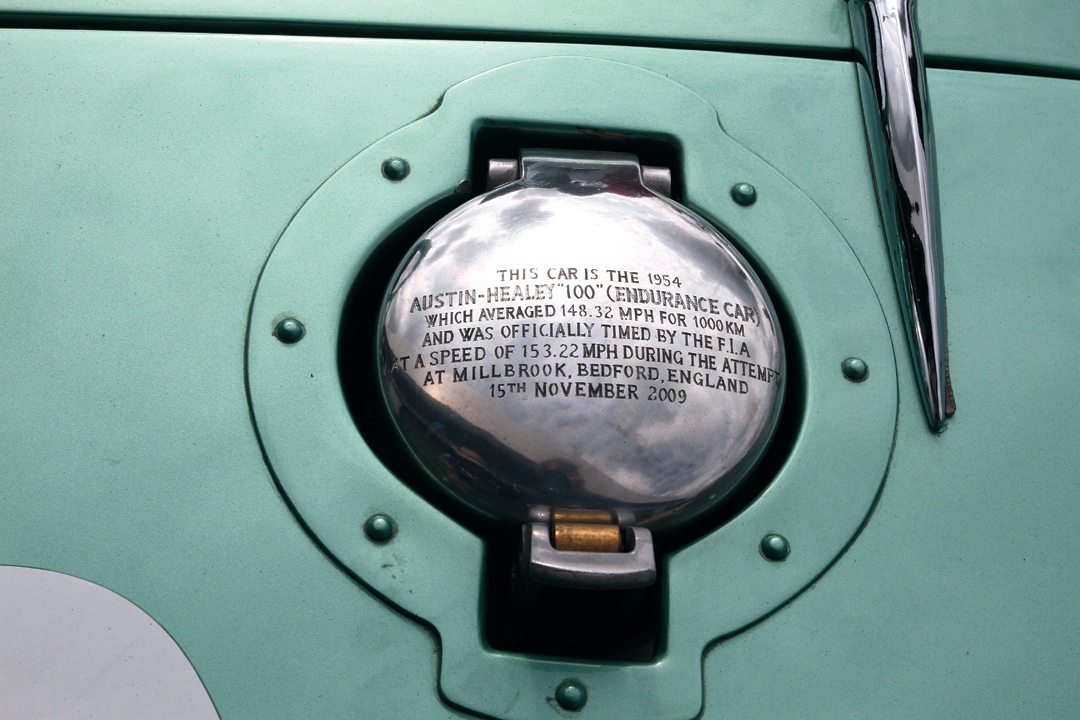

As at Bruntingthorpe, Jeremy Welch again joined Martyn Corfield at the next test session at Millbrook and they were delighted with the results, achieving speeds in excess of 150 mph. From these successes the record attempt was well and truly on. While it was possible to have all the modern gizmos on the car to upgrade performance compared to the period car. The ambition was to run the car as near to period configuration as possible, what would be the point otherwise? Obviously, safety considerations had to be taken into account and it was only these slight modifications, such as a plastic fuel tank, a built-in fire extinguisher system and the use of a Gurney flap to aid stability that were made. Astonishingly though, NO seat belts!!! One other difference was the tire; although the same 16-inch Dunlop wheels were used they were shod with Michelin Pilot tires, which Michelin went to great lengths to develop specifically for the run. On the November 15, 2009 (not an ideal month for great weather in the UK!), the Healey was taken to Millbrook for the record attempt. At the end of the session the car was officially timed at 153.22 mph over a 1,000-kilometer run—4.9 mph faster than the original. After what must be described as the drive of their lives, Corfield and Welch had done it!

It had been no easy drive as Corfield explains: “Driving the car at Millbrook demanded the most intense physical and mental concentration. To put it into context, it really made me appreciate the feats of those former record breakers at the wheel of the Napier-Railton and those records set a Brooklands. The speeds they were putting in at that time and the machinery they were using of that era made for really heroic efforts…it’s just another world. My right arm and shoulder were up against the support brace for the metal tonneau cover for the entire drive. Yes, it was padded, but the centrifugal force while driving left a bruise on my arm for a week afterward. We were driving in an almost prone position to remove ourselves from any of the airflow. Sitting on a period seat, we physically locked ourselves into position for our entire stint, without seat belts, as they were in period. However, the original records were set on a gentle 10-mile oval that created little or no G-force. Millbrook is a rather tight two-mile banked oval that certainly did produce quite aggressive G-forces. Ironically, the reason I wanted to do the record attempt was I thought it safer, from a driving point of view, than racing the car. In reality, give me racing any day!”

Photo: Deniis Welch Motorsport and Crucial Images

Driving the Austin Healey

Changes made to convert the car from a record car to a racecar included removing the stagger by re-aligning the rear axle. The gearing also needed to be changed. The aero safety features were removed and they focused on re-balancing the car for more normal driving conditions rather than on a banked oval. Don’t forget most UK circuits are set for right-hand drive, as most of the corners are right-handed. Driving a left-hand-drive car is quite tricky, unless you’ve balanced the car properly. Ballast had to be introduced to the left of the car, whereas previously they’d lightened the car as much as possible for ultimate speed. Seat, harnesses and a roll hoop to comply with FIA requirements were also fitted. Although these changes seem quite aggressive, they kept the same engine spec, the 16-inch wheels, the steering wheel, in fact most of the original record car as possible has been retained. It is easy to sum these modifications up in a few words, but it has taken many years to hone the car into the racing machine we see today. Bearing the number 550, it now emulates the original 1954 Mille Miglia car.

As previously mentioned, the car is in left-hand-drive configuration, a little different to most UK-owned Healeys, although those of you across the “Pond” will wonder what we Brits are worrying about! However, peripheral vision and the ability to find an apex can cause concern when you’re used to driving a right “hooker.” In the driving seat, it feels like many other cars, but immediately in front of you is the period three-spoke Healey steering wheel, which is very much thinner to hand than the usual racing type. It’s bigger circumference also takes a little getting used to. The knobs and dials are near identical as they would have been in period, with just a couple of modern additions in the name of safety. Indeed the 140 mph speedometer is from the original car, uniquely it has overspray from the original car on the back and completely black-faced—this was to prevent glare. Our run is on the National Circuit at Silverstone on a bright summer morning with a bone-dry track, so ideal conditions. The car has already been warmed up with engine and fluids all at good running temperatures. While the circuit is well known, the car is a little strange, again due to it being left-hand drive, so after some adjusting and a warmup lap, car and driver are in a position to drive at speed for the purpose of this test.

As we cross the start-finish line we’re in fourth gear heading toward our first point of reference, which is the gantry of the old footbridge. It is at this point where, in your mind, you are considering braking and gearing for Copse Corner. We are the only car on track, so we can take it in an ideal situation—braking, but holding fourth gear as we look for the apex and carrying as much momentum as possible. It does take a while to get the car up to an ideal racing speed. Our advantage with this car is that it is lighter than other Healey 100s, with a slightly more powerful engine, but it possesses the distinct disadvantage of the 16-inch wheels we’re running on, which in turn affect the gearing usual Healey’s would have as a norm on a racing 100S or 100M. In reality, one seems to offset the other. In period, the 16-inch Dunlop peg wheels were only used for record attempts, and the 1954 Sebring and Mille Miglia cars. Otherwise, they reverted to normal 15-inch wire wheels for racing. So, we’re carrying more speed into the corner than a normal Healey, to keep up the momentum. If other cars, through this or any other corner, baulked us, “bogging down” of the gears would seriously compromise momentum. We’ve ideally negotiated Copse Corner with a good exit, now moving over to the right for Maggotts, the left corner prior to Becketts. Through here, we drop down to third, taking a late apex. It’s down to second through the right-hand Becketts Corner, always in readiness to accelerate. Handling-wise, through these corners, the car feels very benign and well balanced, so very little oversteer, a little bit of understeer, but not a huge amount of washout. We’ve been able to keep the power on and have exited the corner well to move up through the gears achieving a top speed of 115 mph as we advance down the Wellington Straight toward Brooklands. Moving over to the right, as we approach the corner, we change down to second as we prepare to hug the entrance to the long right-hander at Luffield. On the exit of the Luffield complex, we accelerate hard using as much engine torque as we can possibly get to be at an ideal speed through Woodcote and onto the Start/Finish line to complete the lap. Driving the lap in an ideal situation is pleasing, but with other cars around you in a racing environment this could leave the driver a little frustrated—especially if you had been constantly hampered by needing to build up the necessary impetus required.

Conclusion

There are always problems in trying to replicate something built in a former era, be it a building, a piece of furniture or, in this instance, a racecar. The methods and practices of construction along with materials used are naturally compromised from what was in the day to today. However, I believe a necessary principle to have in place prior to taking on such a feat is to build in the right spirit. Having a mind to appreciate methods and traditions that have obviously changed over the years, but remaining as authentic as possible has to be a key ingredient. In this instance, all manners of modern gadgets and technologies could have soured this project, but those involved preferred to remain as tightly as possible to the original. It is also that the car was only fractionally faster than the original that bears out that principle. I’m sure the team could have beaten the record by a country mile, but that certainly wasn’t the aim. So, this car realistically pays homage to the exploits of the original Bonneville car and those involved with the record-breaking attempts of the 1950s. In that endeavor it has become a record car in its own right. Martyn Corfield, Jeremy Welch and his team at Denis Welch Motorsport should feel proud of this fine example of a period car and all they have achieved with it.

SPECIFICATIONS

Engine: 4 Cylinders

Bore: Standard +30 (88mm)

Stroke: Standard (111mm)

Head: 100S Weslake designed 8 port aluminium with right hand exhaust and induction

Carbration: ”2xSU 1.75″” H6 normally aspirated”

Max rpm:: ”6,000″

Gearbox: “BN2 4 speed, side change non-overdrive.” Straight cut heavy duty mainshaft

Final Drive: 100S crown wheel and pinion 2.69 ratio

Brakes: ”Dunlop type disc brakes 11.25″” front and rear operated by double piston”

Suspension: Front bottom wishbone with coil spring and top location via hydraulic shock absorber (as original) “Rear semi eliptical leaf spring with hydraulic shock absorber, uprated springs and anti-roll ball”

Resources

Bibliography

Healey – The Specials by Geoffrey Healey

Austin Healey – The Story of the Big Healeys by Geoffrey Healey

The Encyclopeadia of Motor Sport by G N Georgano

Periodicals

Motor Sport / Autosport / Autocourse

Special thanks

To Martyn Corfield for allowing us the use of his car, Jeremy Wech and his team at Denis Welch Motorsport