Where do we start with the story of the March 761? In true Sound of Music fashion—at the very beginning. In the late 1960s, a band of four guys, Max Mosley (a barrister), Alan Rees (a former racing driver), Grahame Coaker (engineer and racing driver) and lastly, Robin Herd (a designer), came together to form March. Their dream was to design, build and sell competitive “customer” Formula One racing cars, as well as running a “works” team. It seemed so simple; a Cosworth DFV engine, a Hewland gearbox, an in-house chassis, aluminum body and four lumps of rubber courtesy of Dunlop, Goodyear or Firestone at each corner and anyone could go racing. Funding had now become available to Formula One through sponsorship, as the FIA had relaxed rules governing Grand Prix racing teams, which were now on a similar financial road as American racing series where commercial backing and advertising had been the norm for many years.

Photo: Pete Austin

The 1970 season started incredibly well, of five race starts (two heats at the International Trophy Races, Silverstone) March managed three poles and four wins, a record on a par with the dominant 1954 Mercedes Silver Arrows! So, there was no surprise in Round Three of the championship, when Jackie Stewart again put his March on pole with Chris Amon sharing the front row at the “Jewel in the Crown” Monaco GP. Enter Swedish racing driver Ronnie Peterson, a young, bright, superstar in the making who hit the Formula One grid at Monte Carlo, driving a sixth March entered by Colin Crabbe’s Antique Automobiles racing team. Peterson had given March its racing debut at Cadwell Park, driving the 693 Formula Three car—so he was part of their DNA. He would have been racing earlier in the 1970 season, but his car wasn’t ready. Making the cut for the race was his first hurdle—only 16 cars were allowed to start at Monaco that year—which he did in 13th position. For March, however, the Monaco race showed flaws, only Peterson was classified as a finisher, in 7th place. Siffert and Amon, the works drivers, together with Jackie Stewart’s Tyrrell March all retired (Servoz-Gavin, Stewart’s teammate failing to qualify).

Was the March bubble about to burst? Another pole in Belgium for JYS, and Amon finishing 2nd and fastest lap in the race, suggested not, perhaps it was a mere hiccup. For the next four GPs Jochen Rindt dominated in the Lotus 72—another car that plays a pivotal part in our story. By the end of its debut season, without any serious development, March finished 3rd in the Constructors Championship with 48 points, just behind two established marques, Lotus and Ferrari, so not a bad start.

Although his first season ended with zero points, Ronnie Peterson’s driving style wooed March to offer him a works F1 drive in 1971. From first appearance, the new March 711 looked radical with the “tea-tray” or “Spitfire” wing, as it’s sometimes referred to. It was penned by Frank Costin and Geoff Ferris and was refreshingly distinctive in design, unlike today’s F1 CAD cars. While taking no victories that year, Peterson finished runner-up in the World Championship to Jackie Stewart, who was by then driving Tyrrell’s own chassis.

For 1972, March lost its way. The new 721, a 711 with new bodywork, soon gave way to the 721X (X for experimental) and then to the 721G (G stood for Guinness World Record), which was built in nine days and was basically a Formula Two car with a Cosworth DFV F1 engine. This lackluster equipment let Ronnie Peterson jump ship to John Player Team Lotus for the 1973 season driving D and E versions of the Lotus 72 alongside Emerson Fittipaldi. Peterson’s potential evidenced itself with GP victories in France, Austria, Italy and the USA. In 1974, however, Lotus too took a wrong turn with the John Player Special Lotus 76. Peterson, paired with Jacky Ickx for the season, was given the old upgraded Lotus 72 to race. Despite this, he managed to salvage wins at Monaco, France and Italy to finish 3rd in the World Championship. After rumors of a switch to Shadow, 1975 was again another disastrous year for Ronnie.

Electing to stay with JPS Lotus, he again campaigned the now aged Lotus 72 with interludes of the poor performing Lotus 77 “adjust-a-car” failing to live up to expectations. A season of retirements and lowly race finishes led the relationship between Peterson and Colin Chapman to deteriorate. Chapman’s adage, “If you’re not winning you’re not trying,” together with Peterson’s frustration of trying to wring every last ounce of performance from a car that didn’t function, were the key ingredients to this. It was unfortunate too, that although an excellent driver, Peterson had an inability to relate the precise problems, or possible solutions to mechanical issues to his engineers. Ronnie was a “seat of the pants” driver.

Photo: Pete Austin

However, with Messrs Herd, Mosely and Chapman involved things obviously weren’t straightforward. On this occasion, Chapman was the one hoodwinked. For Peterson to move, Chapman would need a replacement. March had the ideal candidate in Gunnar Nilsson, their works 1975 F3 Champion, who had been knocking on doors trying to get an F1 drive for 1976. The first part of the plan went well for March; Chapman liked Nilsson. The legal-minded Mosely drew into the small print of the contract that Nilsson would only move to Lotus, “if he wanted to,” something Chapman failed to spot until after he’d released Peterson. Initially embarrassed, he had to pay more, but eventually got his man.

For Peterson to move to March, Lella Lombardi, the only woman to finish in the top six in the World Championship (6th, 1975 Spanish GP) would have to be moved to sports cars, taking her Lavazza sponsorship with her. Peterson’s personal sponsor Count Zanon, together with more from an anonymous group of Swedish businessmen, ensured the financials were in position. During the season the car would be painted in a variety of liveries and corporate colors as advertising space was sold on a race-by-race basis. So now, Ronnie Peterson was “back home” in the March team for rest of 1976.

March 761

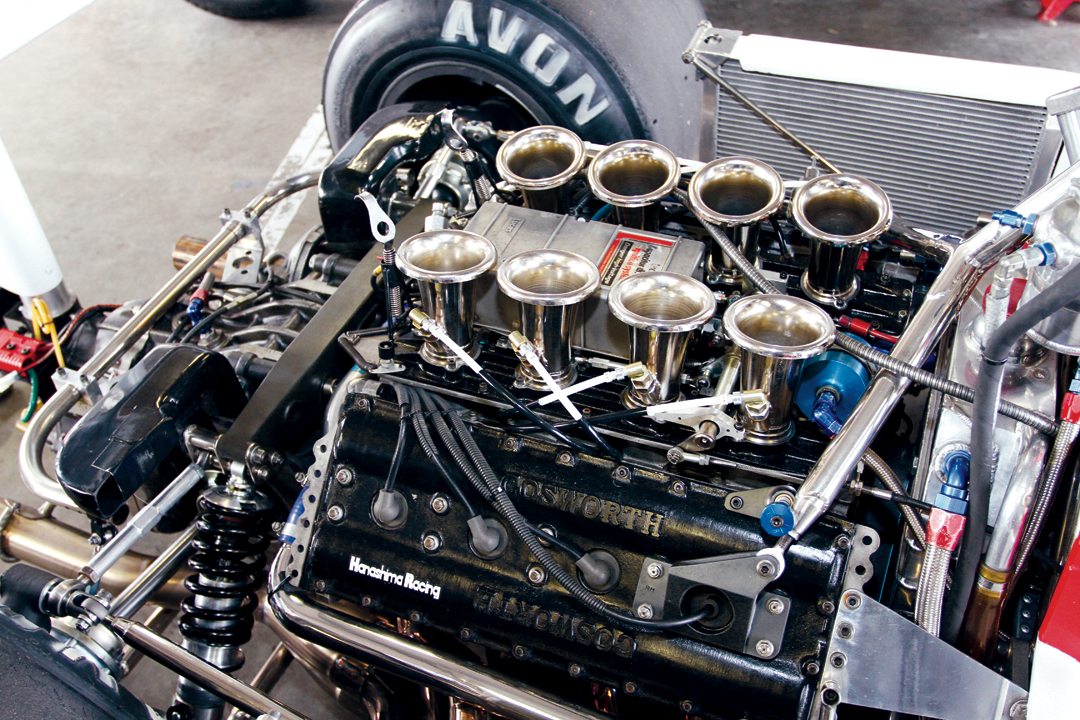

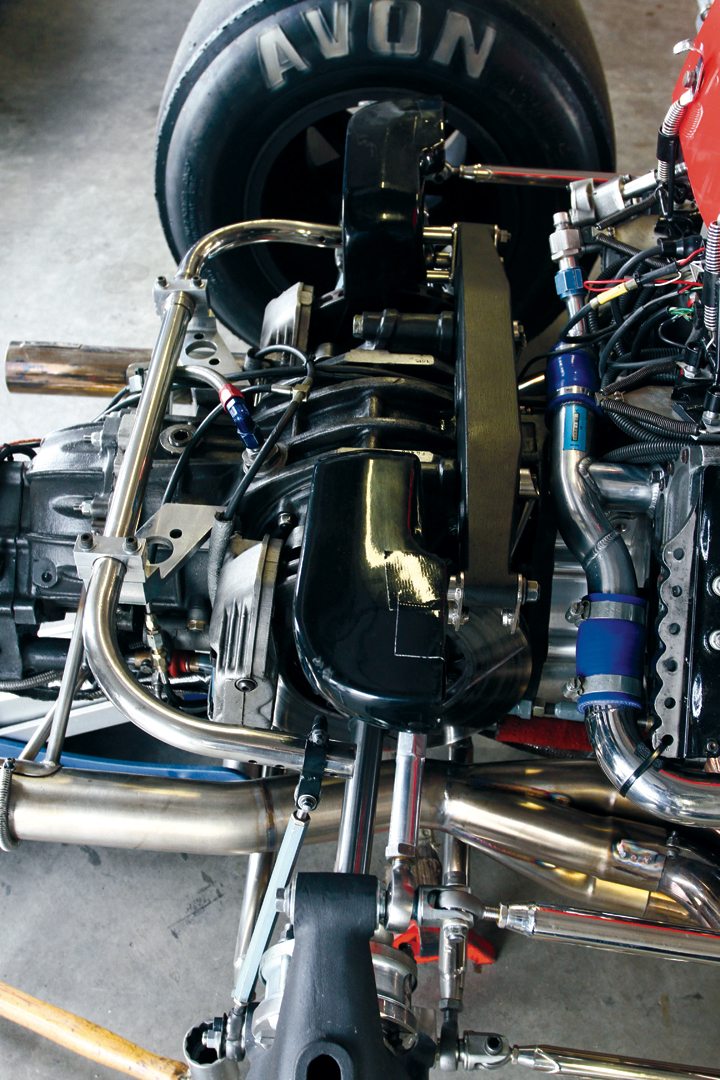

On paper, March was possibly one of the strongest combinations on the entire F1 grid with Peterson, Hans Stuck and Vittorio Brambilla. March Engineering’s contender for the 1976 season, the 761, should really have been named the 751B. However, March challengers were always numbered with the first two numbers being the year, 76 for the 1976 season, and the last number being the formula, F1, hence 761. Most cars were just uprated from the previous season. Modifications were made to stiffen the monocoque; the front track was increased to 56 inches and rear track to 58 inches. The rear suspension was revised where a wishbone replaced bottom parallel arms. At Shadow, designer Tony Southgate had been working on changes in wheelbase. March copied this on the 761, with the wheelbase now able to be altered via a spacer between the engine and gearbox. In short-wheelbase trim the car was 100 inches and long-wheelbase 109 inches. The various Grand Prix circuit layouts dictated the wheelbase length and the type of nose cone used.

For those of you who rely so much on this detail, the chassis numbering system throughout the season is confusing to say the least. Having spoken to many racing mechanics over many years, I’m at a loss as to how so much credence is put on a small metal plate that was frequently transferred from chassis to chassis for export carnet purposes. However, from records available this is what we have: March 761/1, Brambilla’s car, had four tubs over the course of the season. March 761/2 (formerly 751/6) was Stuck’s car for all but the International Trophy race at Silverstone, when Brambilla raced it. March 761/3 (formerly 751/1-2) was Lella Lombardi’s car for the first race in Brazil, then taken over by Peterson for the first half of the season. Merzario was entered to drive March 761/4 from the USGP West onward, the third race of the season, but failed to qualify.

After his very first run in the March 761 at Kyalami, South Africa, prior to the Grand Prix, Peterson commented, “It’s fine when you turn into a corner, but when you come on the power it goes uh, uh, uh.” A few more laps into the session and he was more upbeat, “The handling of the 761 is almost perfect and it’s quick. I noticed even Niki had difficulty in keeping up in his Ferrari.” In the race, a combination of Brambilla wanting to stamp his authority and Depailler’s out of control Tyrrell caused Peterson to retire in the ensuing crash after just 15 laps. With retirements and poor finishing, after five races, there were no points on the table for any of the March drivers. It was off to Monaco to see if fortunes changed.

The cars were prepared in short-wheelbase format to cope with the tight and twisty circuit around the Principality, although Merzario failed to qualify for the race, Peterson, Stuck and Brambilla were delighted with their respective 3rd, 6th and 9th grid spots. Peterson admitted to overdriving during the race in an effort to catch Lauda, but spun out on oil from Hunt’s failing McLaren. Brambilla retired too. Hans Stuck, however, delighted the team with a 4th-place finish and first championship points of the season. At Anderstoorp, Sweden, the March boys worked hard to get a race finish, all finishing outside the points and Stuck retiring with engine problems.

March 761/6

It’s early July, around the time of the French GP at Paul Ricard, France, when our chassis first appears, initially as a spare car. For the French, British and German GPs Peterson used his usual 761/3. He fared well in France qualifying 6th and running as high as 3rd behind leader Hunt and Depailler. In fact, 3rd place and a podium finish was well on the cards until lap 35 when the engine spluttered with a fuel-metering problem. Despite his best efforts, he fell down the pack to eventual retirement. With fuel problems again at Brands Hatch and a crash at the troubled German GP, which left Niki Lauda fighting for his life rather than a World Championship, the March team was in turmoil. Brambilla had crashed three times at the Nürburgring too, leaving the team short of cars capable of running.

Up to that point, Peterson had competed in ten races without scoring a single point. His frustrations were highlighted in various publications of the day when he was quoted as saying, “You can hardly say that life is smiling on me at the moment. Everything’s gone wrong. We’ve tested and are testing and I’m trying my best to be in competitions, but nothing helps.” Ironically, Team Lotus was now on a roll with Mario Andretti and Gunnar Nilsson regularly picking up points—if only he’d stayed?

It was a fresh start at the Österreichring, Austria, with the new 761/6 chassis being raced for the first time. All cars were set up in short-wheelbase configuration. Brambilla, although a rough and ready driver, had given Robin Herd some good feedback on setup, which was translated onto Ronnie’s car too. After qualifying 3rd for the race, Ronnie was leading just two laps after the flag had fallen. Overtaking John Watson’s Penske, which sported the same First National City livery as his March, Peterson’s negative vibes were slowly beginning to dissolve in his mind. It must be said, however, the wet track had also significantly aided the balance and driveability of the car. Slowly, as the race continued and the circuit dried, those ill-handling gremlins started to surface again. According to Peterson the car was now driving like a “very heavy lorry.” As the laps went by, so did the opposition—Watson, Laffite, Nilsson, Hunt and Andretti. At the flag, the Super-Swede really struggled to gain his first precious championship point for a 6th-place finish.

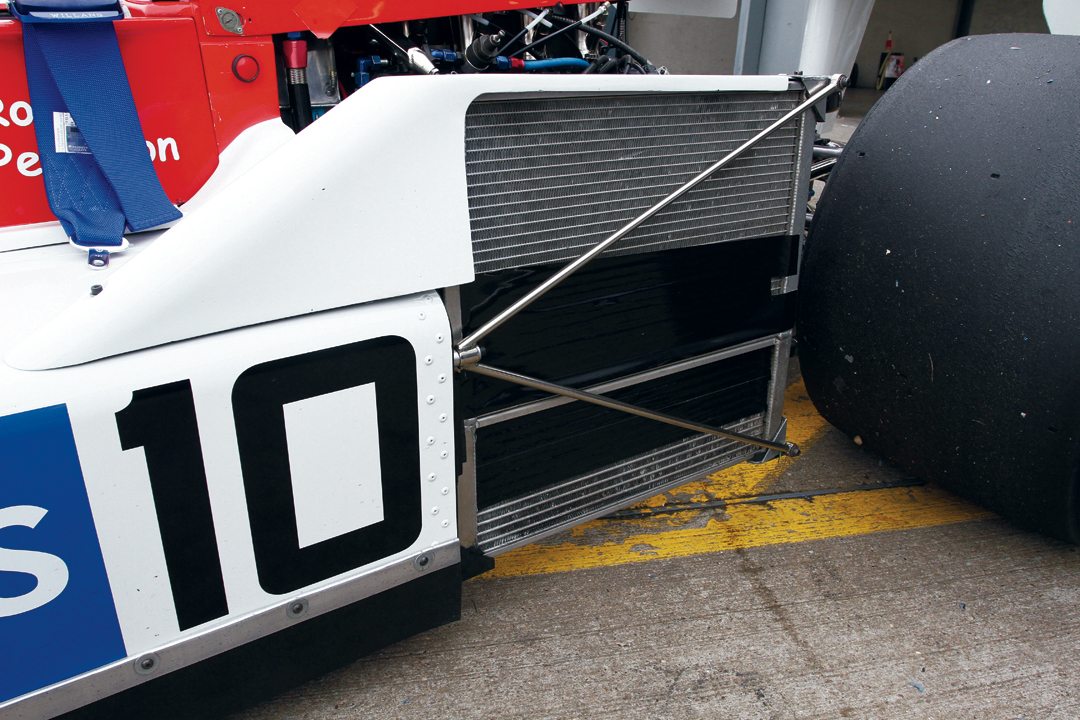

The addition of rubber skirts, attached to the sidepods of the March, aided grip and transformed the driveability of Peterson’s car for the Dutch GP. He put it on pole by just 8/10ths of a second over James Hunt’s McLaren. Overjoyed, he said, “The car went like a dream and for the first time in a long time it was actually really great fun to drive again.” In the race, he battled hard to keep hold of the lead, but Hunt’s McLaren and then Watson’s Penske got by. Robin Herd remarked that the 761 had never been driven so hard. The front tires simply couldn’t handle the treatment as the car had developed significant understeer. By lap 10, Ronnie was down to 5th, he lost his oil pressure and again it was game over.

The prelude to the Italian GP was all about Niki Lauda’s remarkable return to his Ferrari driving seat. Some years later, he confessed that part of his motivation was the thought that Ferrari would sign Ronnie Peterson to replace him. Peterson was Lauda’s tutor at March some years previous; Lauda knew how capable the Swede was, especially in a competitive car. In fact, Lauda needn’t have worried as Peterson had already signed to drive the six-wheeled Project 34 car for Tyrrell Team in 1977. In qualifying at Monza, politics played a significant part. All season long there was acrimony between the race authorities and McLaren, tires too big, car too big and now fuel irregularities were being investigated. After final qualifying samples of fuel taken from the McLarens and John Watson’s Penske, all were found to exceed the permitted 100 Octane. So, those cars lost their grid positions, and faced exclusion from the race. Indeed, only some politicking by Guy Edwards with the minor teams allowed the three cars to start. Amid this, First National City (FNC), Penske’s principal sponsor, were duly embarrassed. They had a stand full of VIP guests at the race to cheer on their team, which had won the Austrian GP. The thought of their car being eliminated before the flag had even fallen would be a pr disaster. Frantic discussions were held with March and the FNC livery, formerly used in Austria, was reinstated on Peterson’s car. For his part, the Super Swede put on a breathtaking performance. From 8th on the grid, the March 761 charged to the front. By lap four, Peterson was 2nd, by lap 10 he was leading! After the pounding the car had taken at Zandvoort, Peterson was worried the fragile car would fail again, but Mother Nature stepped in to help—it began to rain. As Peterson continued to push, he was completely unaware of the confusion that prevailed in the pits. Organizers were deliberating on whether the race should be stopped or not. A black flag and a sign with a white cross were shown on the pit straight. Drivers were confused; some slowed, some pitted, others—including Peterson—just carried on regardless. After a few laps, the organizers removed the signs and the race continued. By this time Peterson was becoming nervous his car might break, but he saw pit signals that Reggazoni’s Ferrari was catching him, so he had to press on. His maxim “win or vanish” saved the day. Risking car and engine on the second to last lap he was flat out and took the lap record. He was overjoyed to see the flag on the final lap. It was the third time Peterson had won the race (equalling a record set by Nuvolari, Fangio, Ascari and Moss), but a magical first time for March. Ronnie Peterson gave his victor’s trophy to Robin Herd, a measure of the respect he had for the team.

Photo: Chris Willows

In Canada, hopes that the car was now on another level seemed to be confirmed by 2nd spot on the grid, but after ten laps Ronnie said, “The car was absolutely impossible to drive. It wanted to go one way and I wanted to go another. I had great big blisters on my hands when I got to the finish.” Ninth place was the best the hard-working Swede could manage. Watkins Glen, the next race was affected by rain for the first two qualifying sessions. However, Peterson and Brambilla took the second row of the grid behind Hunt’s McLaren and Scheckter’s Tyrrell, showing renewed pace. Despite a good grid spot, Peterson had crashed his car during Saturday qualifying, and although repaired, damage to the shock absorbers wasn’t discovered until just before the start of the race and far too late to fix. The car lasted just 12 laps.

The final round at Mount Fuji, Japan, weatherwise, was a continuation of Watkins Glen. Peterson and 761/6 battled with the elements for the last time, finishing qualifying with a 9th-place grid spot. The race was delayed by two hours. Some said it shouldn’t have been run. It was a case of driving carefully to the flag rather than racing, such were the conditions. Other than the lead car, most drivers were blinded by spray. Water also got into the engines and the electrics too. After just half a lap it was sayonara, the March gasped and gave up, leaving Peterson to park it safely and take a long walk back to the pits and on to Tyrrell for the following season.

Photo: Simon Lewis

For 1977, the car was converted to 761B/1 for the first part of the year, which included twin-caliper brakes, revised uprights and a reduced wheelbase to 98.4 inches. South African driver Ian Scheckter, elder brother of Jody, raced the car in the first half of the year, with a couple of interludes from Hans Stuck and Brian Henton when Scheckter was injured. Lowly grid places and race retirements were all that could be managed. After crash damage in the Austrian GP, March 761/6 was taken back to the Bicester factory and converted back to the original 761/6 specification in which Peterson had famously won at the Autodromo Nazionale, Monza. The car was subsequently given to Ronnie Peterson and remained in the Ronnie Peterson Museum until 2007.

Currently, the car is owned by Japanese driver Katsu Kobota and looked after by Zul Racing of Derby, England. The car is campaigned in various Historic F1 Championships, including the FIA Masters championship.

Driving March 761/6

Our test of the car is at a cold, but bright, Donington Circuit. The car is resplendent in the First National City, red, white and blue livery, and is prepared as it was at Monza on that September afternoon in 1976. With the name Ronnie Peterson emblazoned on the cockpit sides, you realize you’re about to drive Ronnie’s car!

We are using the national layout (excludes the GP Loop) and there is little heat in the track. The undulating geography at Donington will act as a great test of suspension, brakes and overall handling, as well as torque and power of the DFV Cosworth engine and Hewland 5-speed gearbox. These were all areas of fragility in period. All systems of the car are warmed and primed prior to driving. Tires have been artificially heated in electric tire blankets to get them to a reasonable operating temperature that will ensure the car grips the surface from the outset.

Photo: LAT

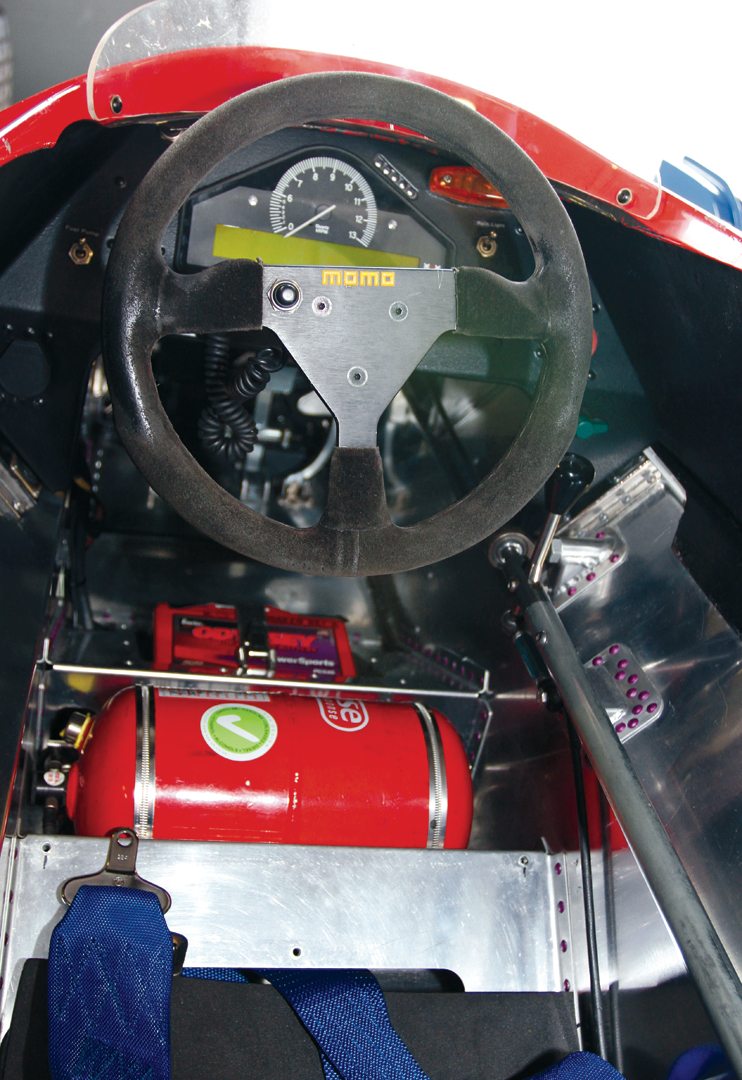

While this is a Formula One car, now after nearly 40 years since it took to the track in serious World Championship anger, the cockpit looks fairly sparse in relation to more contemporary cars. The simple removable steering wheel has no appendages and is there for a sole purpose. The dash too is uncluttered, but has a modern digital analogue rev counter, with digital oil and water temperature display as opposed to period mechanical dials. While reasonably tight, the cockpit is by no means uncomfortable; in fact it allows relatively good arm movement without being restrictive. The gear stick is ideally placed on the right and is easily accessed for smooth operation. Frontal visibility is unrestricted, and while at a standstill the small rear view mirrors seem quite adequate, at speed and with surface vibration, vision will no-doubt be compromised. Foot pedals feel comfortable and are easily operated.

After being pushed from the garage onto the pit apron it’s time to go. The V8 Cosworth engine blasts into life and after a couple of blips on the accelerator it’s time to get in gear and off on an out lap to get a good feel of the car and its idiosyncrasies prior to stepping on the gas for our test. After a couple of what nowadays are referred to as installation laps the car, tires and brakes are fully up to temperature, so we’re set for our “flying” lap.

Photo: Maureen Magee

As we cross the start/finish line we’re flat out in fifth and the right-hand Redgate Corner is looming fast. It’s heavy braking now to scrub off the speed, down two gears as we steer into the corner always preparing to get a good exit ready for the Craners. We use the kerb out of Redgate and accelerate back up to fifth gear as we descend through Hollywood, a shallow right and then left, to the Craner Curves. Through the Curves it’s down one gear as we approach Old Hairpin, a 90-degree right rather than a true hairpin, but the nadir of the circuit. Out of Old Hairpin and it’s hard on the gas and back up to fifth as we climb toward two shallow left turns through Schwantz Curve. It’s flat out here and you can feel the G-forces pulling at your neck muscles. A right at McLeans follows, it’s an odd corner, you can’t see the apex and previous knowledge of the circuit comes into play. One gear down and hopefully hit the apex, full gas again accelerating hard out; this has to be measured to get a good line in preparation for Coppice. Up to this point, the car is well balanced, no over- or understeer and we’re generally feeling at one with it. It’s slightly downhill from McLeans then up to Coppice, again a blind apex right-hand corner. If we’re going to have problems it will be here. The corner is directly on the flight path for descending aircraft landing at East Midlands Airport. The track is subject to being covered in a light sheen of Kerosene from the engines of low flying planes. It’s the first time the car feels slightly out of control with the loss of downforce as we brake, slow, lose a gear and turn right toward the direction of the blind apex. Understeering slightly, concentration is at maximum. Luckily, today it’s dry. If it had been wet things would be so much more difficult. The car goes very light, particularly at the front, as we negotiate the crest of the hill. We’re now driving literally blind and our view from the cockpit is mainly sky! Thankfully, local knowledge has ensured we’ve got it right. From here, it’s hard out, top gear and flat reaching a speed of around 165 mph at around 10,000 rpm down the Dunlop Straight. As it’s the national circuit, the next and last corners before we complete our lap is the Esses —hard right and then left onto the Wheatcroft Straight. Preparing for the corner, in your mind you know if you’re too fast you’ll simply continue straight on. The first hard right approaches, step on the brakes, scrub off speed and lose two gears, down to third. The car is reacting well and quite stable given the maneuver. The steering responds well to the rather violent flick right and back left. Full throttle and back up to top gear to cross the start finish line to complete our lap.

Today, how this car would have behaved over two hours of hard competition is not known. Donington is particularly hard on brakes as, although very flowing, it’s a series of flat-out straights with tight corners. The steel brakes would take a great deal of punishment over a Grand Prix distance. In period, we know the car was fragile—particularly in the initial races. The brakes were improved as the season went on and the addition of the rubber skirts seemed to help the balance and grip too. We’re in one piece; the car has behaved well and given a very satisfying run.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the March 761 can be said to be a less than average car in relation to other cars it competed against on the grid in 1970. It was basic and fragile, yet when questions were asked of it to deliver it somehow did—albeit rarely. No question, Ronnie Peterson was a great driver. Yet, whether it was his character, lack of understanding or inability to communicate, he had a deficiency in conveying necessary information to engineers and mechanics to try to improve the situation. This wasn’t just a problem he had at March; we can see how Colin Chapman became frustrated with this impediment, as well. It is interesting too, to understand the role Vittorio Brambilla played within the team, indeed the “Gorilla of Monza,” known for his aggressive driving style, did have the technical ability to go some way to “sorting” the car. It’s also fascinating to see the improvement the rubber skirts made to increase both performance and handling in these embryonic days of understanding ground-effect racing cars. Perhaps, a driver with more technical ability could have helped develop the car into a regular podium visitor. However, they may have also lacked that Peterson magical driving style, which always seemed to get something out of nothing. At the end of the 1976 season, to give some understanding of the achievement of March Engineering, it’s good to be reminded of what they had built since their inception in late 1969: 43 Formula One cars; 134 Formula Two cars; 150 Formula Three cars; 12 Formula 5000 cars; 109 Formula Atlantic cars; 37 Group 5 2-liter sports cars and 38 Group 5 3-liter sports cars. Some feat! Maybe, they spread themselves too thin?

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: Aluminum Monocoque

Suspension: Front: Double wishbone / coil springs and shocks | Rear: Parallel toe links and radius rods / coil springs and shocks

Engine: Ford Cosworth DFV V8

Gearbox: Hewland FG400 5-speed

Brakes: Girling

Steering: Rack and pinion

Wheels: Front: 13-inch diameter / 10 inches wide | Rear: 13-inch diameter / 17 inches wide

Wheelbase 97.99 inches

Track – front 55.71 inches

Track – rear 60.55 inches

Weight 1265 pounds

THANKS/Resources

The Viking Drivers by Frederick Petersens

Memories of Ronnie Peterson by Joakim Thedin and Thomas Hagg

Motor Racing Year 1977 Edition by John Blunsden

The Story of March by Mike Lawrence

A-Z of Formula Racing Cars by David Hodges

March by Alan Henry

Autosport and Motor Sport periodicals of the era.

SINCERE THANKS TO:

Katsu Kubota for the use of March 761/6

Liaz Jakhara of ZUL Racing, Derby.

Bob Adams and the circuit staff and track marshals at Donington Circuit.