1971 Datsun 240Z

The aristocratically named Giuliano Musumeci rather boxy machines called the Cedric, believing these would Greco is the president of Nissan Italia, and for five sun-filled days, he and Nissan Italia’s general manager, Alessandro Cacciotti, guided the Datsun 240Z rally car round the coast of Sicily, cross country through the Sicilian mountains and along the twisting roads of the old Targa Florio. Towards the end, with a few hours of free time available, they told VRJ the story of this car, which now resides in Nissan’s Museum. It was, they said, the 1973 Monte Carlo 3rd place finishing car in the hands of Rauno Altonen and the now even more famous Jean Todt, manager of Ferrari’s Formula One effort. They also said this car had done the East African Safari Rally in 1972, and had won, though they also made it clear they felt the car was better doing this event rather than “resting” in a museum! The two Italians had loved the trials and tribulations of the historic Giro di Sicilia and were now looking forward to a day of recreating the Targa Florio. Just before they did this, they generously handed over the keys and pointed towards the coastal road: “See what you think…it’s a very civilized car.”

Datsun Goes Rallying

Datsun began rallying long before the mighty 240Z came along; in fact, as long ago as 1930, but that was mainly confined to Japan and their first international rally was not until 1958 when they sent the 210 off to Australia to tackle the one-lap Australia Mobil Gas Trial. The car won and ensured a place in Datsun/Nissan history for Yutaka Katayama, a rising executive who built and raced cars himself and got his own marketing department behind the Australian project. The company then tackled the prestigious East African Safari Rally in 1963 with a variety of Cedrics and Bluebird 311s. They were not successful but the company had decided that competition would be part of their public image, which was not easy when they produced appeal to the British, amongst others.

Photo: Peter Collins

Development of the rally Bluebird 411 SSS led to success at the tough Canadian Winter Rally in 1967, where it won, and the reliability of this model saw 411s taking part in the big Baja off-road events, along with some Nissan pick-up trucks. The Cedrics were sent back to the Safari Rally in 1967 and 1968, again with limited success, but in 1969 the new Bluebird 510 SSS won the class and the team prize, and an outright victory in 1970.

The Arrival of the 240Z

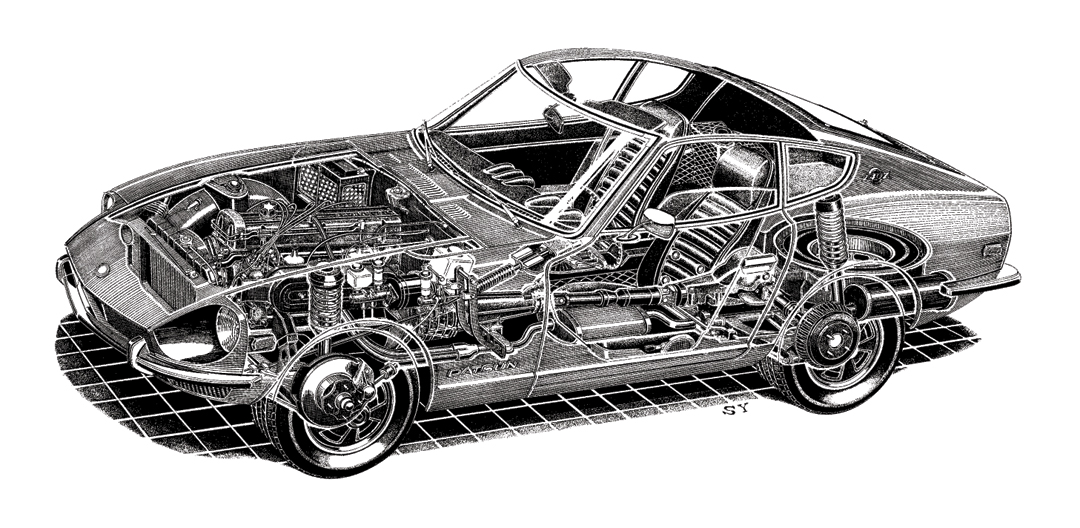

Datsun departed totally from their traditional approach, and when the 240Z was introduced in 1969, it was an all-new package. Though based on a six-cylinder-powered saloon, the 240Z boasted 150 bhp at 5,600 rpm, had a five-speed gear box and very stylish bodywork. It was unusual for a high-performance sports car, as it used the familiar MacPherson strut in the front and rear suspension. At the rear there were wide-based lower wishbones and the differential and suspension were mounted on a stout sub- frame which was bolted to the integral body/chassis unit. The brakes were Girlings, though made under license in Japan by Sumitomo, with front discs and finned drums at the rear. The early production cars had 14-in. wheels with either 4.5-in. or 5.5-in. width rims and Dunlop Sport 175-14 tires. The car looked very much like the company had competition in mind when it was designed, being a straight two-seater with no provision for carrying a third person, and no trunk, though the rear-opening window reveals a generous flat space for luggage…or lots of rally equipment!

Photo: Peter Collins

The 240Z was an enormous success story for Datsun, and 720,000 cars, including the later 260Z and 280Z, were sold by the end of production in 1980. It became the world’s best-selling sports car. The car was promoted, especially in the U.S., as something in the mold of the highly rated Austin Healey 3000. The Japanese admiration for British cars and tradition kept appearing in their own vehicles. The 240Z had a clear advantage over the 1600 SSS predecessor with its 2.4-liter engine giving greater power and substantially better torque. It was a heavier car than the saloons but it was quicker and stronger. Nevertheless, the independent strut suspension on four wheels made it difficult to drive fast, and though the Nissan Corporation hired skilled drivers like Rauno Altonen and Shekar Mehta, even they found it a handful, Mehta saying it “was an accident waiting to happen.” In his case, that turned out to be true!

The 240Z had huge appeal, in spite of its handling problems. It was a high-performance sports car in the tradition of the big Healey, and like its contemporary, the Lancia Stratos, attracted many privateers into rallying, as well as being an important works car. It did well in national and regional rallies, though the main objective, as far as Datsun was concerned, was winning the two premier events—the Monte Carlo and Safari rallies. The 240Z was entered in the 1970 RAC Rally in Britain, and the drivers included Edgar Herrmann, who had been a long time team member, Tony Fall and Rauno Altonen, but all the cars had differential problems and failed to finish. For 1971, Rauno Altonen and Paul Easter managed to finish 5th overall at the Monte Carlo Rally, while a second car finished 10th. Tony Fall won the Welsh Rally but by far the event of 1971 for Datsun was their victory on the Safari.

Photo: Peter Collins

Veteran German driver Edgar Herrmann had driven the Safari several times, and his first attempt for Datsun had been in 1967. Herrmann was supposed to drive for Porsche in 1969, but the car was withdrawn and he quickly found himself in a Datsun 510 with codriver Hans Schuller. They started last on a very dusty Safari and finished 6th, helping to ensure a win in the team prize for Datsun. After a very gritty drive, the pair won the 1970 Safari in a 510, and were in 11th starting position for the 1971 event. Teammates Mehta-Doughty and Altonen-Easter also had good starting spots in their 240Zs, and a total of 38 Datsuns start- ed the ’71 Safari. The large entry number constituting a clear sign of how important it was to Nissan.

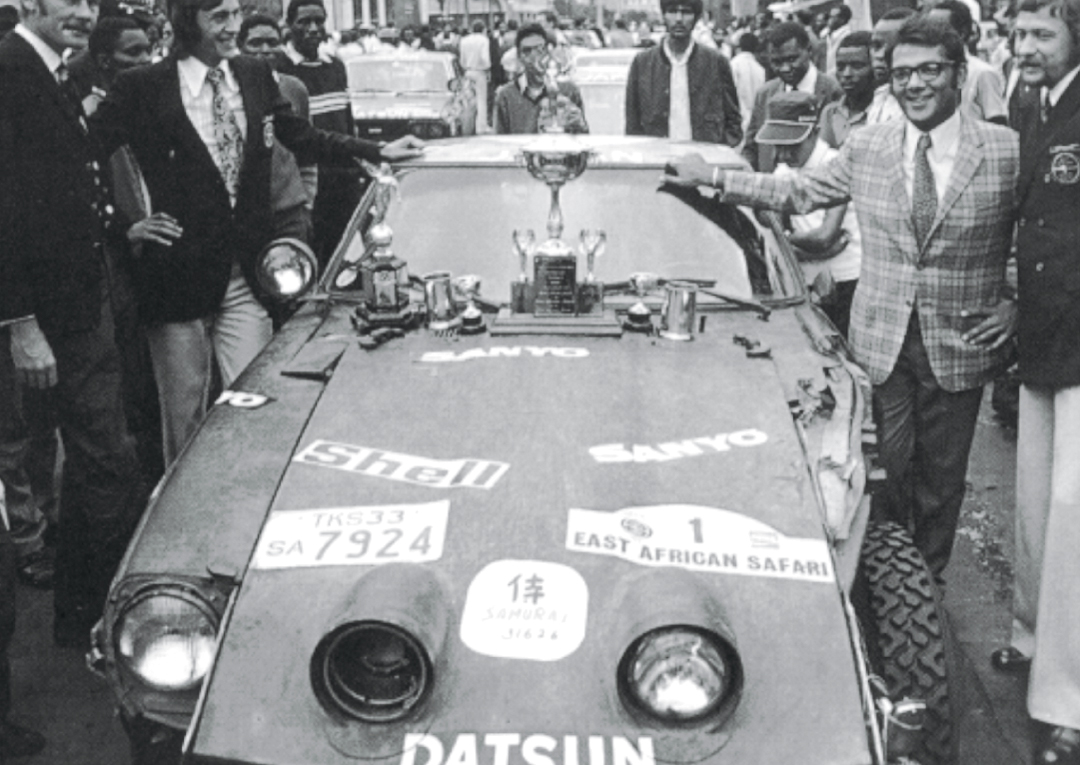

Altonen led the early stages to Mombassa, ahead of Herrmann-Schuller, the Porsche of Waldegard, and Jack Simonian in a 240Z which had a tire blow at 130 mph; he was lucky to survive the crash. Herrmann was in 4th by Dar Es Salaam in Tanzania. Waldegard led after Altonen had suspension repairs but then lost all his fuel when mechanics left the filler cap off. On the return to Nairobi, Zasada moved his Porsche into the lead, and Herrmann-Schuller cruised the whole leg at 130 mph. Herrmann had a strange but lucky break on the road to Kampala, Uganda when he was about to be given an undeserved penalty. None other than the President Idi Amin stepped in to assist, as he was out on the stage doing marshaling duty! Later, Altonen and Mehta both moved their 240Zs past Herrmann when he crashed and broke a half shaft. However, his co-driver Schuller was able to fix it well enough to get it to the next service point. After the others had problems, Herrmann resumed the lead, but was being chased hard by Ugandan Asian Mehta in his home country. Then Mehta got stuck in a mud hole near Mount Kenya and just as he was about to be towed out, Herrmann landed in the same place. The Landrover rescue vehicle pulled them both out at the same time, but Herrmann hadn’t lost any time while Mehta had been stuck for some while. Thus Mehta lost the rally to Herrmann by three minutes. He would have to wait two years for his revenge.

Photo: Ed McDonough Collection

1972 was not particularly successful in rally terms, though 240Z sales had grown and grown, and the cars were being raced in a wide variety of events. They were not expensive to buy, and a reasonable amount of sorting could improve the handling. They were a real hit with American amateur racers, and they appeared in large numbers in national and local rallies.

Early in 1972, the works team converged on the Monte Carlo Rally. Whereas the Safari was characterized by parched and dusty roads, with the occasional flood turning vast areas into quagmires, the Monte could always count on ice and snow, where average speeds would be higher over longer periods, and where weather conditions could change subtly, making it hard for the driver to “read” the road. The Monte traditionally started from nine European capitals, and headed over fairly easy routes to Monte Carlo. The event then roared around 10 local stages in southern France and returned to Monte Carlo. The top 60 cars would then undergo a third and final stage, usually a 12-hour night run over the slippery mountain roads of the Alp Maritime. This was a high-speed section with perilous drops, and where conditions would shift from dry to snow to black ice and back.

Altonen and Easter managed 5th in 1971, and the team was hoping for bigger things in 1972. Altonen practiced regularly before the event, though anticipating particular conditions on a specific stage was impossible. Altonen and Jean Todt were in car number five, with the Japanese registration TKS33SA4150. They remained in a consistently good position for the entire event but just could not catch the flying Lancia Fulvia of Sandro Munari, and the Porsche 911S of race and rally driver Gerard Larousse. The front-wheel-drive Lancia and the rear-engine Porsche were far better suited to the changing conditions of the Monte in 1972, and Nissan would never realize its aim of winning this event, although the Altonen-Todt performance was nothing less than sensational in a car much happier on dry roads. Nissan had few good results that year, with 5th, 6th and 10th on the Safari, and Altonen taking 2nd in the Australia Southern Cross Rally. Herrmann-Schuller got the 5th spot in the Safari after breaking half shafts, though they had managed to lead, but all the cars had numerous problems. The Ford Escort of Hannu Mikkola eventually won from Zasada’s Porsche.

There was no success at the 1973 Monte Carlo Rally so a huge effort was being made to win the Safari again. This time Hermann-Schuller were driving for Nissan for the last time, and led at the beginning but soon retired with mechanical woes. The Escorts of Roger Clark and Hannu Mikkola then led, Clark holding 1st until the return to Nairobi. Shekar Mehta had a catalog of disasters, including hitting a flock of birds, which removed their night driving lights. Clark then had problems but was still in front while Mikkola drove into the back of Zasada’s Porsche, which rolled. Timo Makinen rolled his Escort, Bert Shankland his Peugeot, and then Altonen’s 240Z hit a bank and rolled— Mehta hit the same bank but only tore off a fender. Mikkola’s steering broke so Kallstrom’s Bluebird 1800 SSS then led with Mehta’s wreck (the car my Italian hosts in Sicily said was the same beautiful machine I took for a drive to Palermo!) Mehta eventually got past Kallstrom but they finished with the same number of penalty points so the event ended in a dead heat. The final standings were ultimately decided on a count back of fastest times over the stages, resulting in Mehta winning by just one point. He had been right about the 240Z being an accident waiting to happen, but this time it didn’t happen to him. Well, it did, but he won anyway!

While the 240Z continued to be a useful rally car, some teams tried the 260Z and later the 280Z, and Kallstrom was 4th in the 1974 Safari with a 260Z. The big Datsuns tried European events, but the car was a real handful in rallies like the RAC, where drivers were on blind stages in a car that wasn’t all that great in the visibility department.

Driving TKS 33SA 4150

It has to be said at the outset that these were rally cars, and they were damaged, repaired, written off, rebodied, had new chassis, had chassis plates and registration numbers switched and put on new cars, so keeping track of them was not the art form it is today, though why anyone would want to today is another question.

Nevertheless, I had a fairly big shock when I slid into the seat of the big red machine, late on a warm Sicilian afternoon. The car had been restored to road trim, I thought, until later research showed that these cars were not all that different from road cars, most of the rally tuning going into making them stronger and more reliable. Having not long ago had the chance to sample the modern Ford Focus which Carlos Sainz drove in the Rally of Corsica in 2001, it is astonishing what rally cars have become, and this of course may be their undoing. The Focus was an earth-bound jet aircraft in comparison, and when the full rally mode was switched on in the cockpit, Dr. Jekyll left and Mr. Hyde took over. It was a performance monster. The Datsun 240Z, in comparison, was a silky pussycat with a bit of muscle and plenty of class.

Nevertheless, I had a fairly big shock when I slid into the seat of the big red machine, late on a warm Sicilian afternoon. The car had been restored to road trim, I thought, until later research showed that these cars were not all that different from road cars, most of the rally tuning going into making them stronger and more reliable. Having not long ago had the chance to sample the modern Ford Focus which Carlos Sainz drove in the Rally of Corsica in 2001, it is astonishing what rally cars have become, and this of course may be their undoing. The Focus was an earth-bound jet aircraft in comparison, and when the full rally mode was switched on in the cockpit, Dr. Jekyll left and Mr. Hyde took over. It was a performance monster. The Datsun 240Z, in comparison, was a silky pussycat with a bit of muscle and plenty of class.

Greco and Cacciato had thoroughly enjoyed their hundreds of kilometers around the Giro di Sicilia, which included the original route of the event, part of which was the ‘Big Madonie’ Targa Florio route, truly a wonderful mix of fast roads with mountainous stages and city streets all part of the fun. They said it was like driving a new car, it was so well behaved, with good steering, brakes and gear box, and they were able to give it some proper exercise, especially when they came up against a Lancia Fulvia of the type which beat this car at Monte Carlo in 1972! They did, however, find it very hot inside, so the Safari must have been a good means of losing weight. They were impressed with the torque and smoothness of acceleration, and compare it favorably with the competition 280Z they also have in the Nissan Museum in Rome.

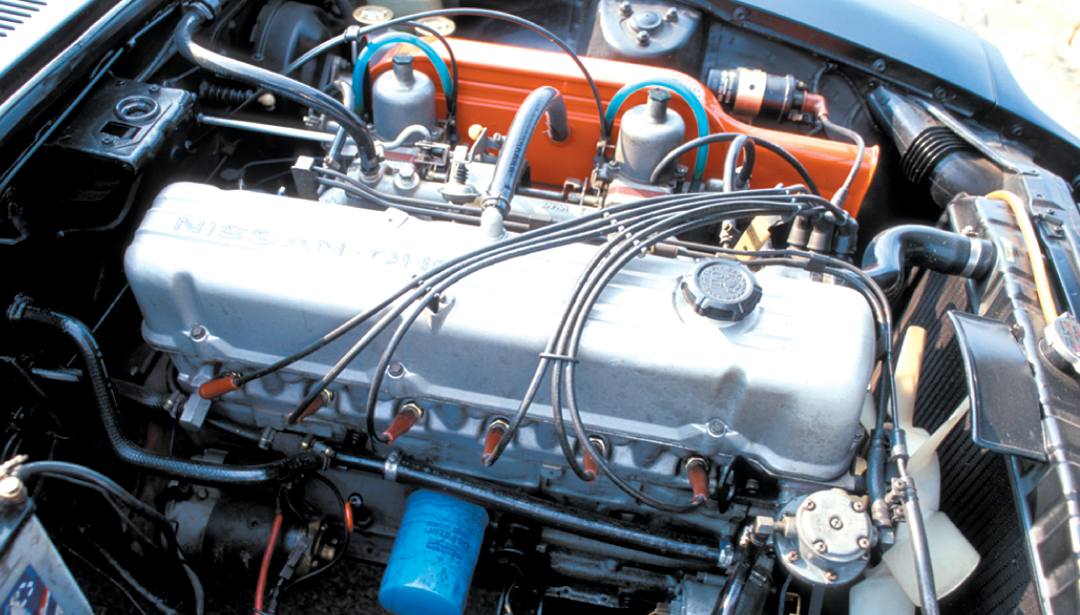

The car was on Bridgestone tires for the Giro di Sicilia, 195/70R/14 on the front and rear. It was bedecked with hooks and towing brackets to cope with the demands of the Safari Rally, all of which seemed out of context in Sicily! It had thick seats, a period wood-rimmed steering wheel, with few special instruments. It had normal gauges but foot rests for the co-driver to brace himself. The seating position is fairly low, though comfortable for easy road use. Under the bonnet is the elongated six-cylinder engine with twin carburetors on the left side, possibly Japanese-made SU copies. Purposeful twin exhausts accentuate the rear of the car, while numerous extra lights adorn the rear and the top, though they tended to move around for the different events, sometimes located in the grill, and sometimes on the roof…until they got knocked off in a roll or by low flying Zebras!

The competition exhaust booms in the ears, and the car feels heavy at low speeds, but soon “loses” weight as the speed rises. I would guess that the torque curve for the 240Z is pretty flat, as it is smooth and impressive from the off, with no peaky periods that I could detect. Flashing along the coast road towards Palermo, on what was the old Targa Florio route next to the blue-green sea, fourth and fifth gear acceleration was very pleasant and responsive. It has a relatively low top-gear ratio but high final drive.

After stopping to take in the scenery, the take-off in first is good but not staggering while the engine revs right up to the 7,000 rpm red-line without strain. The car has a degree of low-speed punch without having to use the gear box, which works well but is slightly vague in feel.

The 240Z looks like it is going to be nose-heavy, but the engine is set back in the chassis and the overall weight balance is good, with 51% over the front wheels. This allows a higher steering ratio with 2.7 turns in a 33-foot lock. I found the weight distribution and suspension geometry make the handling pretty neutral, and I didn’t experience the “accident-about-to-happen” experienced by drivers of the period. The MacPherson struts keep the roll angle quite small even in quick corners, and the independent set-up means the car feels stable on the rougher roads of Sicily. The disc-drum combination with the servo assistance still requires a fair amount of pedal pressure, especially in a sudden stop, but the car remains stable under all braking conditions. The springing tends to feel soft but that is hard to judge without knowing how this museum car is looked after, while the damping is stiff, but not too stiff. The ground clearance is high, necessary for all that rally work on nasty surfaces, but the handling doesn’t suffer as a result…though it must have been something on glare ice downhill, on off-camber roads with big drops on the side! I was surprised that there is virtually no wind noise in this car, even at 100+ mph. There was some creaking from the rear sub-frame and a bit of knocking from the diff…you can eliminate that with smooth gear changes I am told. All in all, this was a time warp experience, a very pleasant and tactile one.

Buying & Owning a 240Z

We have said this before: you can have one, but not this one. This car will never leave the ownership of Nissan. However, especially for Americans, the 240Z remains a very practical classic, being readily available in good condition for reasonable prices. Rally cars are harder to find. They were so good, that they were run until they were finished, so there just aren’t many left. Through the 1980s, they weren’t that much in demand, so you can now find a nice one for $4,000 to $10,000, and if you want the Safari or Monte Carlo lookalike, it’s not that hard to do. A firm in Holland is now producing them. And there is no shortage of spares, so you can keep one of these going for many years to come.

Specifications

Wheelbase: 2,305 mm

Body: Steel unitary construction with sub-frames, 2-door sports coupe

Suspension: MacPherson type struts all round; front: track control arms with rear-mounted tie bars and anti-roll bar; rear: wishbones acting as both swinging arms and radius rods

Weight: 1,169 kg

Engine: 6-cylinder in-line, mounted longitudinally in front, two twin choke Solex carburetors or Hitachi-built SU type

Capacity: 2397 cc

Power: 151 bhp production; 220 bhp rally version

Bore & stroke: 83 mm x 73.7 mm

Compression: 10.0 to 1

Valves Per Cylinder: 2

Cams: 1 ohc

Transmission: 5-speed gear box with 4th as a direct gear

Tires: Bridgestone 195 x 14

Resources

Klein, B.

Rally Cars

2000 Konemann Publishing, Germany. ISBN: 3-8290-4625-1

Thanks to Carl Beck and Paul Crossen, and to Giuliano Musumeci Greco and Alessandro Cacciato of Nissan Italia.