I have been smitten with the early Austin-Healeys for a long time. In 1965, home with a pocket of cash after six weeks of ROTC Summer Camp, I thought I could convince my mother to help me buy a car for my senior year of college. The first car I looked at was a 1955 Healey 100 BN1. I was a bit puzzled by the weird, backwards three-speed shifter, but I was in love with the look of the car. My mother had different ideas about how I might use that cash, so I continued to take the bus from home to school. As a young Army officer, I thought about buying a new Healey, but there was something about the six-cylinder cars that I didn’t care for – they just didn’t look as good as that Healey 100. In his book, “Austin-Healey 100 In Detail,” Bill Piggott describes how I felt (and more) about the 100: “…today’s enthusiasts can see the BN2 and particularly the 100M version for what it is, perhaps the best combination of all the individual factors that went into the various models of Big Healeys right up to the last 3000s. It has the beautiful simplicity of line of the first cars, bereft of later adornment; it has the light weight, light steering, excellent handling and economy of fuel that the four-cylinder engine gives, but it is equipped with the excellent and robust four-speed and overdrive gearbox and rear axle of the later cars.” Pete Brock chose the 100 to be one of his “20 Revolutionary Automobiles that Shaped Our Modern World,” saying, “The 100 prototype was an aesthetic masterpiece that immediately caught the sporting public’s fancy when it debuted at the 1952 London Motor Show. Although it featured rather compromised internals, its price and availability made it every man’s dream sports car. It might have lacked the performance of a Jaguar XK120, but the price undercut the Jag’s popularity. The Austin-Healey 100, like the MG TC and XK120, was eventually redesigned to emerge as the larger, better-performing Healey 3000. However, like the later MGs and Jags, the 3000 never really matched the spare, graceful lines of the original.”

Donald Healey

The story of the Austin-Healey 100 could not have happened without Donald Mitchell Healey, and not just because of the car’s name. Healey was a visionary and a competitor, and his vision included building excellent sports cars for the road and the track. Donald Healey was born in 1898 to a family who ran a local store, but his father was an early auto hobbyist. Healey grew up around interesting automobiles, including a 1907 Panhard that was eventually replaced with an R.M.C. (Regal Motor Car Company), an American car sold in the UK after WWI. Fascinated by machines, Healey apprenticed with Sopwith Aviation in 1914, where he received his early engineering education. The chaos on the continent got Healey to enlist in the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in 1915, where he trained as a pilot. He received his pilot’s certificate in June 1916, two years before he earned an automobile driver’s license.

During the war, Healey flew bombing missions on the continent and anti-zeppelin flights in England. Flying was dangerous, whether in war or peace, and Healey experienced two crashes, one in France and a more serious one in England which resulted in his being invalided out of the RFC. With his background at Sopwith, Healey was hired by the Air Ministry and spent the rest of the war inspecting parts being manufactured for airplanes. Healey intended to go back to work for Sopwith after the war, but the company had changed from manufacturing airplanes to motorcycles. Their A.B.C. motorcycle was not successful, and the company eventually failed. Healey decided to return to school for engineering, where he studied both “ordinary” and automotive engineering.

Healey opened a repair shop near the family store and learned how to repair cars. The repair business appears to have been successful enough to allow Healey to enter rallies, where he proved to be an excellent rallyist. His first big success was a win at the 1928 Bournemouth Rally. The rally was run similar to the Monte Carlo Rally, where cars started at different points in the UK and rallied to the finish in Bournemouth. Healey’s 832-cc Triumph Super Seven was the smallest of the cars starting from John o’ Groats in northern Scotland. His first attempt at the Monte Carlo Rally was not as successful. There were 16 possible starting points and routes for the rally in 1929. The longer the route chosen, the more points could be scored. Teams had to arrive in Monaco by 10:00am on January 21st, 1929, in order to qualify as a finisher. Healey chose Riga, Latvia, which he believed would give him the longest route without bad weather. His forecasting ability proved to be marginal. Snow in Estonia prevented him from reaching Riga, so he changed his starting point to Berlin, Germany. He battled through blizzards, fog and ice through Germany, Belgium, and France but was still on time until he got lost on the Corniche d’Or, the road from France into Monaco. He arrived at the final control at 10:02am and was disqualified. Later that year, he won the Brighton Motor Rally in the Triumph, some consolation for his lose in the Monte.

The 1930s must have been a lot of fun for Healey. The decade provided a number of successes and some bizarre stories as he competed in a variety of rallies in cars he prepared. He started the 1930 Monte Carlo Rally in Tallinn, Estonia, in his Triumph and finished seventh overall and the first British entrant. He started the 1931 Monte in Stavanger, Norway, this time in an Invicta in the over 1100-cc class. He had an incident in Sweden on the way to the start and had to disconnect one of the rear brakes. He was unable to fix the damage until the finish in Monaco, but still, he won the rally. He also won the Alpine Rally in 1931 and received the Coupe des Glaciers for having no penalty points. He finished second in an Invicta at the 1932 Monte, then had a crash with a horse-drawn sleigh in 1933 and did not finish.

Early in 1933, Healey worked to organize a team of Rileys for the Alpine Rally, which they won. He then tried to get Riley and Invicta to join together making a company Healey believed would be very competitive. Lord Nuffield put paid to that effort by buying Riley. That took Healey back to Triumph. He joined the company in September 1933, eventually rising to be its Technical Director. Healey saw the potential in the new Triumph Gloria and worked to modify it to be a rally car. For the 1934 Monte, he started in Athens in the Gloria in the 1500-cc class, finishing third overall and first in class. His next effort was to build a Triumph Dolomite for 1935. It had a copy of an Alfa Romeo 2.3-liter engine, an effort approved by Vittorio Jano at Alfa. Healey decreased the engine bore so displacement would be 2-liters, added a supercharger, and installed 16” hydraulic brakes. He started in Umea, Sweden, and was doing well until he hit a moving train at a rail crossing in the fog in Belgium. The train tore the nose off the car but only did minor damage to the train. Still, Healey and his navigator were arrested and jailed until they could prove that they could pay for the damage to the train. The Dolomite was rebuilt for the 1936 Monte Carlo Rally, and Healey finished eighth overall and first Brit.

During the lead up to WWII, Triumph sold their motorcycle business after not getting many military contracts as a result of the small size of the company. It was eventually taken over by the Air Ministry, and Healey was appointed General Manager, where he developed a way to test airplane carburetors on the bench. He also did cadet training in the Royal Air Force. Eventually he went to work for Humber on their armored cars. During this time, though, Healey was developing plans for his own company once the war was over.

Donald Healey Motor Company

Healey had some ideas about what he wanted in a car that would bear his name. He invited two friends from Rootes, A.C. “Sammy” Sampietro, an engine and suspension specialist, and Ben Bowden, a body specialist, to lunch to discuss his ideas. Based on Healey’s description, Bowden drew a car on the tablecloth that became the Healey Westland. It was the first new post-WWII sports car. With an investment of £20,000, the Donald Healey Motor Company was founded. The goal for the car was good handling and a 100 mph top speed. Chassis were built by Westland Aeroparts, Sampietro designed the front suspension, and Victor Riley agreed to provide engines and rear axles. The engine, a 2.4-liter Riley twincam, was a pre-war design that produced 90 bhp. Adding twin SU carburetors and a new intake manifold raised the power to 104 bhp. Riley also helped Healey get the steel he needed for his car at a time when steel was still in short supply and controlled by the government.

Roadster bodies were built by Westland Aeroparts, with saloon bodies coming from Elliot. Those firms gave their names to the models whose bodies they produced. A Westland was taken to Belgium in 1946 for a roadtest on a stretch of roadway often used for speed tests. Motor conducted the test and got a speed of 106.56 mph over one kilometer, so Healey’s goal of at least 100 mph was achieved. The result of the very positive publicity was the ability to build a new assembly area for the Healey cars at Warwick. Between 1946 and 1954, production expanded to include Westland and Abbott open cars and Elliot and Tickford saloons.

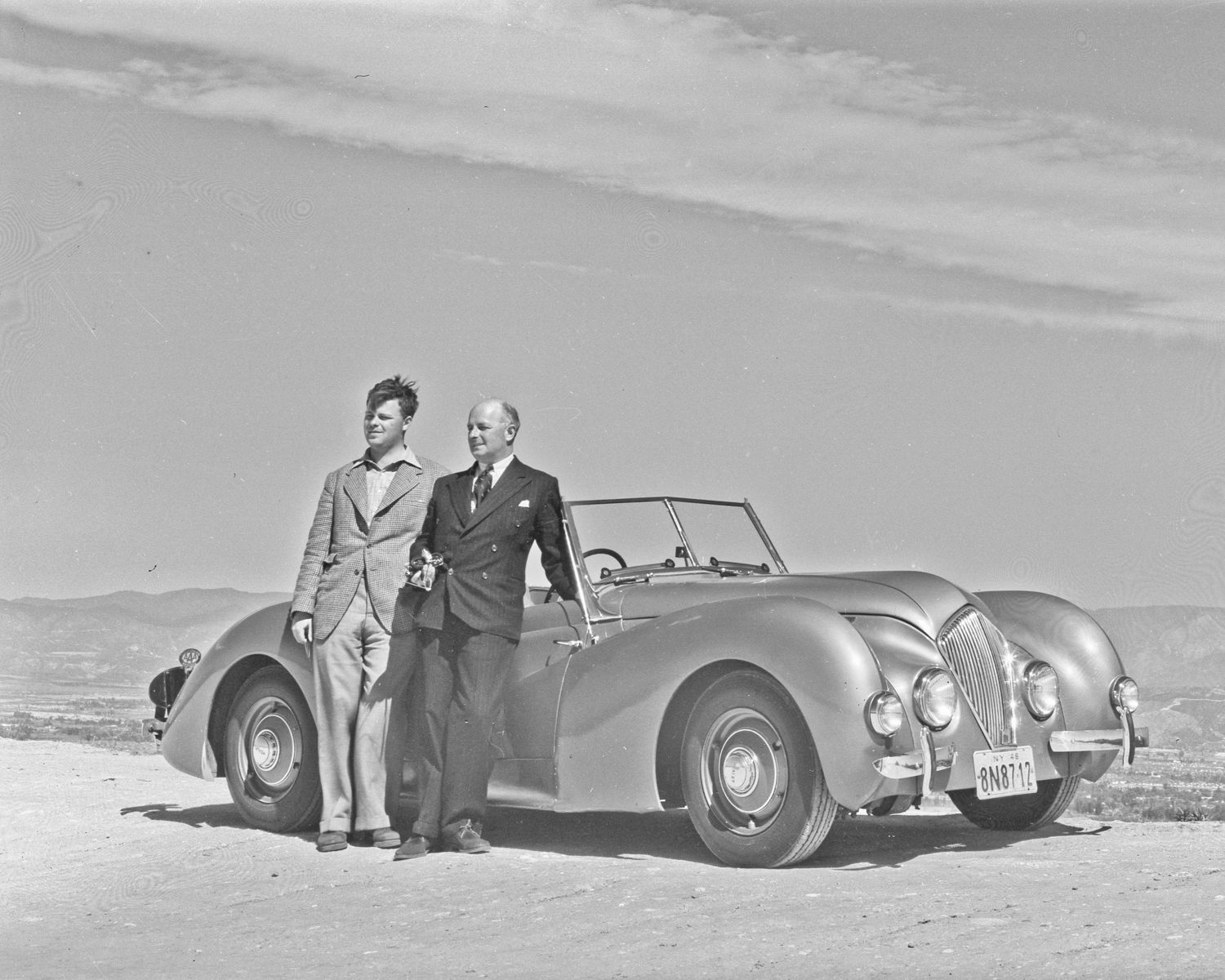

Healey realized early in his planning that the United States would be the best market for his cars, so during the winter of 1948, he and his son, Geoff, toured the U.S. in a Westland, visiting potential dealers to promote sales of their cars. Geoffrey Healey became Managing Director of the company, while his brother, Brian, worked at marketing the cars. Healey still believed in competition as a way to attract attention to his cars, so he and Geoff entered the Mille Miglia in 1948 with a stock Healey roadster whose only modifications were a set of race tires. They finished ninth overall and fourth in the unlimited sports car class.

The British government was responsible for the next Healey automobile. When the government doubled the purchase tax on cars costing £1000 or more, Healey introduced the Silverstone roadster in July 1949. It was designed to cost less than £1000, and had a stark body, cycle fenders, and a retractable windscreen. A total of 105 were sold during two years of production. A Silverstone came second overall in the Alpine rally and won a team prize in a production race at Silverstone circuit.

A chance encounter while traveling to the U.S. on the Queen Elizabeth ocean liner, led to the next adventure for Healey. Another passenger on the ship was George Mason, president of Nash Kelvinator. Mason and Healey hit it off, and the eventual result of the meeting was the Nash-Healey. Once again, racing was important to the success of the model. Nash-Healeys were entered in the Mille Miglia and Le Mans. In 1952, a Nash-Healey finished third overall at Le Mans behind two much more powerful Mercedes racecars.

Healey Hundred

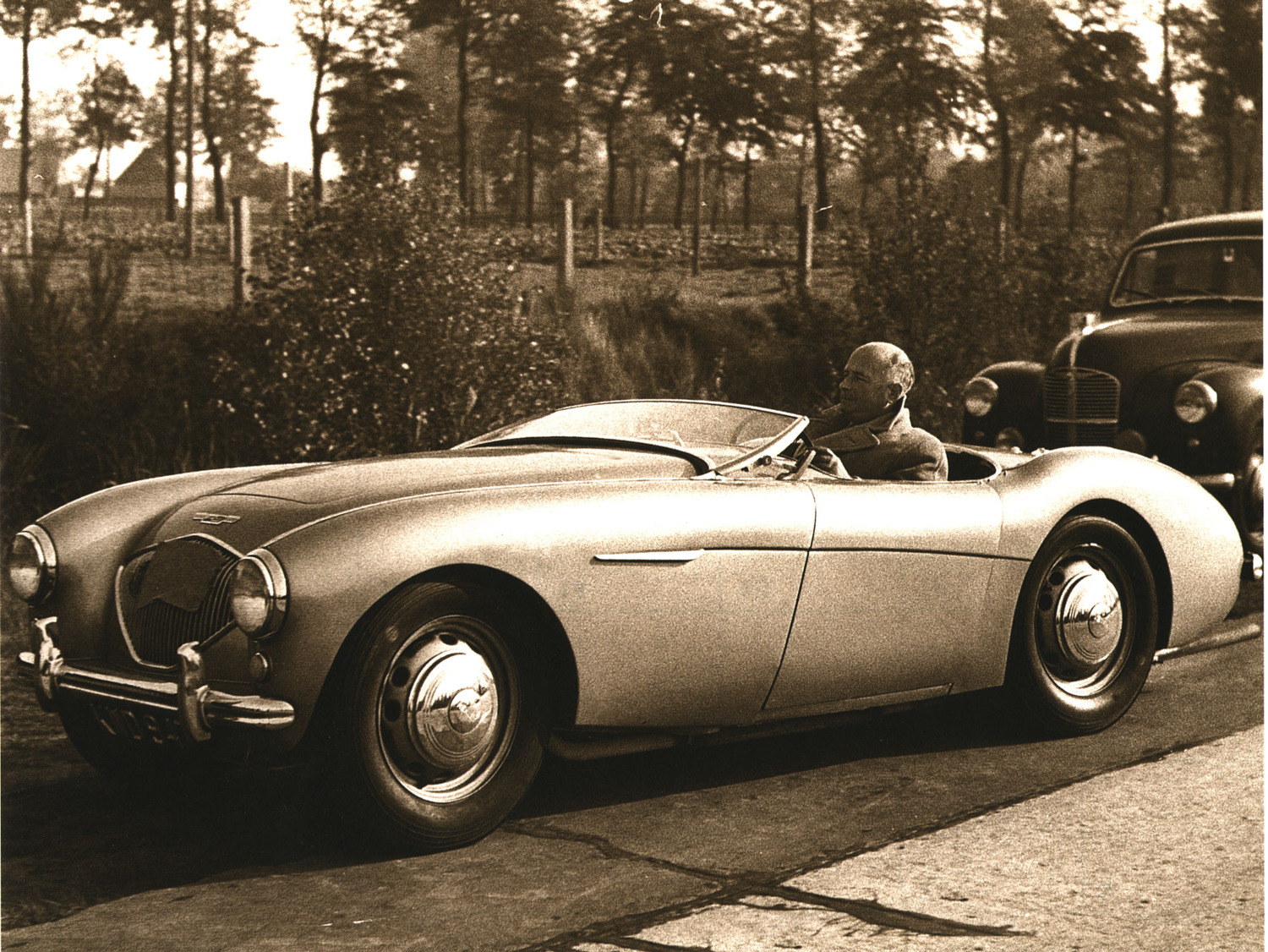

The Healey Hundred was introduced to the public at the 1952 Earls Court Show. The only part of the car that Healey didn’t like was the grille, so the car was displayed with the nose toward the post to hide the grille. With a list price of £850, three hundred orders, many from the U.S., were taken at the show. When Leonard Lord saw the Hundred, he wanted it. That night, at dinner, Healey and Lord agreed that the car would become the Austin-Healey 100 and would be produced by Austin in much greater numbers than could be done at Healey’s plant in Warwick. On the first day of the show, it was called the Healey Hundred, but new badges were quickly fabricated for the car representing its new name.

Austin-Healey 100

The Healey Hundred became the Austin-Healey 100 almost overnight simply by changing the badges, but the differences between the Hundred and the 100 were significant. The biggest difference was in the potential for production. Healey Hundred production would have been very limited because the Donald Healey Motor Company was small. With the addition of Austin to the name, the Austin-Healey 100 would compete on even ground with Triumph, MG, and even Jaguar. Donald Healey benefitted significantly from the union, including these seven inducements:

- Donald Healey would retain the copyright to the design; Austin would make no changes to that design; Healey would be responsible for all design changes.

- The Donald Healey Motor Company would receive royalties, and Donald Healey would receive a consultancy fee.

- Healey would build 25 pre-production cars for promotions and competition, and Austin would fund the competition program for the car.

- The car would be an Austin-Healey and would be produced at Longbridge as soon as the production line was built.

- Austin would reimburse Donald Healey for the cost to design the car.

- Once production began, the Donald Healey Motor Company had sole selling rights for three months (Healey’s son Brian remembers that part of the agreement as being for 500 cars.)

- The Donald Healey Motor Company would have the selling rights to U.S. service members stationed in the UK.

The union gave Donald Healey financial security, removed the headache of warranty issues, created the competition program Healey wanted, and insured that the car would be mass produced. BMC got a car to fill in its line of models, took advantage of unused production capacity at Longbridge, made use of overproduced Austin A90 parts, and would be a source of income for the corporation. Lord set the selling price at £750, making it even more competitive in the market. In his book, “Austin-Healey 100 in Detail,” Bill Piggott observed: “. . . the affordable and practical 100 mph car had arrived.”

The designation for the new Austin-Healey would be “BN1.” Production was proposed at 100 cars per week, a target that Tickford could not reach. As a replacement for body production, Donald Healey recommended Jensen Motors Limited. Jensen had recently lost a contract to build bodies for the Austin A40, so they had the capacity. Ultimately, Jensen would produce about 72,000 bodies for Austin-Healeys through the end of production in 1967. The process to manufacture an Austin-Healey 100 had three significant steps. First, the chassis was built by John Thompson Motor Pressings Limited. The chassis then went to Jensen for the body to be installed. The panels for the body were pressed by Boulton Paul and Company. Then the chassis, with body, went initially to Warwick and subsequently to Longbridge for the driveline and final assembly. The first chassis and body from Jensen arrived at Warwick on January 6, 1953. This second car (the first was the prototype), was the first production Austin-Healey. After it was finished, it was sent to Los Angeles. Car #3 was shipped to New York on the HMS Queen Mary on February 18th. The fourth and fifth cars were completed by the end of February. These five cars differed from the prototype. Brake drum diameters were increased to 11 inches from 10, the steering was reengineered, the rear window in the top was made larger, and the exhaust pipe was turned up at the rear to prevent grounding. Most noticeable, though, was that the headlights were raised two inches to be legal. This was accomplished by raising the forward part of the fenders and making the top of the grille more rounded. There were four special test cars built at the same time. The production cars were all painted Healey light metallic blue, while the test cars were all light green. By the end of 1953, around 2,000 cars had been produced.

Donald Healey once again proved that he was hands on. He travelled to Los Angeles, gathered up car #2, AHX2, and toured the U.S. in it. Car #3, AHX3, was displayed in the Austin showroom in New York City for one day before being shown at the 1953 New York Motor Show. After the show, AHX3 was driven to Sebring where it was displayed during the 12-hour race and then on to Miami for the World’s Fair Motor Show. It won the Grand Premium Award for best car in the show. Next up was Palm Beach, where Briggs Cunningham and others placed orders for the car. Finally, AHX3 was driven across the U.S. to San Francisco, visiting dealerships along the way. Donald Healey met the car in San Francisco and drove it back to New York by way of Chicago and Detroit. During his drives, Healey kept in touch with the factory, suggesting changes and improvements to the production cars, including heat shielding to reduce the heat in the cabin from the exhaust system.

Healey’s next focus was on finishing the competition cars. The special test cars, designated AHR5 to AHR8, needed his attention. Back in Warwick, Roger Menadue was managing work on the cars in the experimental workshop. The cars had to look stock, so Jensen did the bodies in Birmingham alloy with alloy pseudo bumpers on three of the special test cars. The fourth had no bumpers, since it was destined to be used for land speed record attempts. Donald Healey considered British Racing Green to be an unlucky color, but he still wanted to use some shade of green, since green was the color designated for British racing cars. The cars were finished in Dockers light metallic green, the same color used on the earlier Healey saloons. The competition cars were very different than the production cars in nearly every way but their look. The chassis was lightened and stiffened, revised Girling brakes were installed, it had a thicker anti-roll bar and re-valved shocks, a larger fuel tank, and Dunlop race tires. Nuts and bolts were drilled and wire-tied. The engines were built by Austin and included nitrated crankshafts, lightened flywheel and pistons, a cam with higher lift and longer overlap, stronger valve springs, larger carburetors, and a light weight radiator. The transmission was a stronger unit from an Austin taxi with a Borg and Beck clutch and a heavy duty, faster overdrive unit.

Total production at Warwick amounted to 20 cars. There was the prototype, 15 pre-production cars, and the four test cars. Production at Long Bridge began in June 1953, ending the run of cars produced in Healey’s original factory. Several of these early cars were sent to shows in Europe. AHX4 went to the Frankfurt Motor Show in March 1953. Following what seemed to be a family tradition, Geoff Healey drove AHR5 to the Geneva Motor Show that same month. His drive and testing by journalists and dealers eventually put 3000 miles on that test car.

But the test cars were intended to race, not go to shows. The first competition event for an Austin-Healey was International Lyons-Charbonniéres Rally in March 1953. Driver for the rally was Gregor Grant, the editor of Autosport. His navigator was Peter Reese. The car they drove was the prototype. The rally lasted four days and included hillclimbs and other speed events. By the end of the rally, the poor roads had battered the Austin-Healey, but it finished 50th of the 153 entrants. Seventy did not finish. Grant, in his article, called the Austin-Healey a “first class sports car.” With their low ground clearance, though, Healeys would never made great rally cars. Next up was the May 1953 Mille Miglia. Two Austin-Healeys and one Nash-Healey were entered. The cars were equipped with full interiors and had bumpers so they would look stock. One car failed because of issues with the throttle linkage and the other with clutch problems.

Lessons were learned from the two rallies, and improvements were made to the cars being readied for Le Mans in June. Five cars were prepared – two Nash-Healeys and three Austin-Healeys, including one designated as the spare. Because of a road accident, the spare was pressed into service for the race. The Austin-Healeys were given race numbers 33 and 34. Number 33 was driven by Gordon Wilkins and Marcel Becquest; number 34’s drivers were Johnny Lockett and Maurice Gatsonides. According to Donald Healey, his Austin-Healeys were the “most stock cars in the race.” The cars performed well, finishing 12th (#34) and 14th (#33) overall. After the race, one of the cars was driven back to England, and the other was taken on holiday by Geoff Healey, adding 1500 miles to those already on the car. One of the special test cars was taken to Sebring in 1954, where it finished third even though it had broken a rocker arm and was on three cylinders.

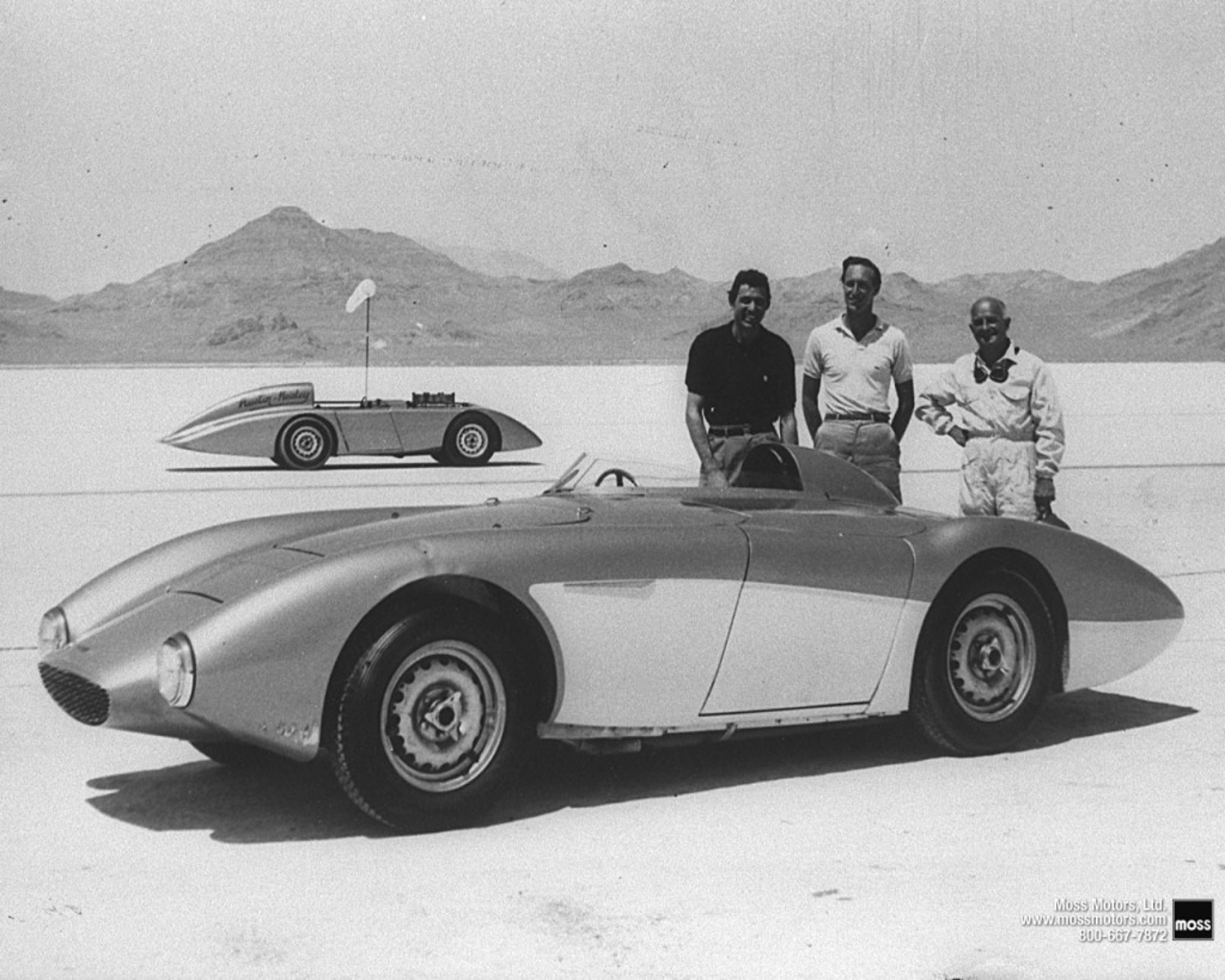

The test car that was built for land speed records was taken to Bonneville. Donald Healey ran the car at 203.11 mph in 1954, making it only the fifteenth wheel driven car to exceed 200 mph. It was supercharged and had a special streamlined body, so it wasn’t exactly production. There were other drivers of the car who ran for endurance records, and the list is interesting. It includes George Eyston, Carroll Shelby, Mort Goodall, Roy Jackson Moore, and actor Jackie Cooper.

Production rose slowly. The goal was 200 cars per week by the end of 1954, but only 50 per week were rolling off the line. Before 1955 came to a close, production was 85-120 per week. New colors were being added. Initially, all cars were Healey blue, then a red car and a white car appeared in the marque’s first color brochure. They were followed by a black car and another that was fawn and cream, then seven that were metallic gray and one that was maroon. In 1955, some excellent improvements were included in the car that became the BN2.

The changes that were made resulted in the BN2 being a much improved automobile. The BN1 had been plagued with transmission problems, so a four-speed was sourced from the six-cylinder Austin Westminster. It had reasonably close ratios, was very strong, used the conventional H-pattern, and had an overdrive that worked on the top two gears, making it a six-speed. The transmission came with a shorter gear lever located closer to the centerline of the car than in the BN1. External changes were subtle, including wheel arches and front fenders that were slightly higher and, more noticeable, a swage line across the doors and the front of the rear fenders that continued behind the rear wheel arch to the very back of the fenders. Together with the transmission, it was the suspension improvements that made the BN2 special. It received larger 2 ½ inch drums and shoes, front hubs were improved using roller bearings, ride height was raised with longer front springs, and front lower wishbones were modified to improve steering lock. The BN2 was a very nice car and eventually accounted for 31% of Austin-Healey sales. There were two special versions of the BN2 – a 100S competition version and a stunning 100M. Both are quite rare.

Although Lord had assured Healey that “I won’t let my men at Longbridge bugger about with your design,” his assurance only lasted until 1956. That is when the decision was made to put a 2639-cc six cylinder engine in the Healey. It was a long engine, causing the car to be lengthened by two inches. The model, which was available as a two or as a 2+2, was called the 100/6. It sported a new grille and a small air intake on the hood. The heavier 100/6 showed no improvement in performance over the 100/4. Sadly, the changes made it a less attractive car than the 100/4.

1956 BN2-L228159

Our subject car was built on August 29, 1955. It apparently had a rough life until it was found by the current owner’s father, Charlie Warner, in an unoccupied building in Richmond, Indiana. Warner found his first Austin-Healey while looking for an MGA. He paid $1000 for it in 1974, and his son, Jeff, used it while in college in Kentucky. His enthusiasm grew when he saw an ad in the local paper asking people to come to a meeting to establish an Austin-Healey club. Twenty people showed up for the meeting, and the club eventually grew to more than 70 members, with Warner as president on several occasions. His interest in Healeys was part of his reasoning to build a 24×30 building so he could restore and sell the cars. He bought parts and cars wherever he could find them, and he got good enough at restoring them that people started coming to him to have their cars restored. His expertise at his hobby made him very popular with Healey owners.

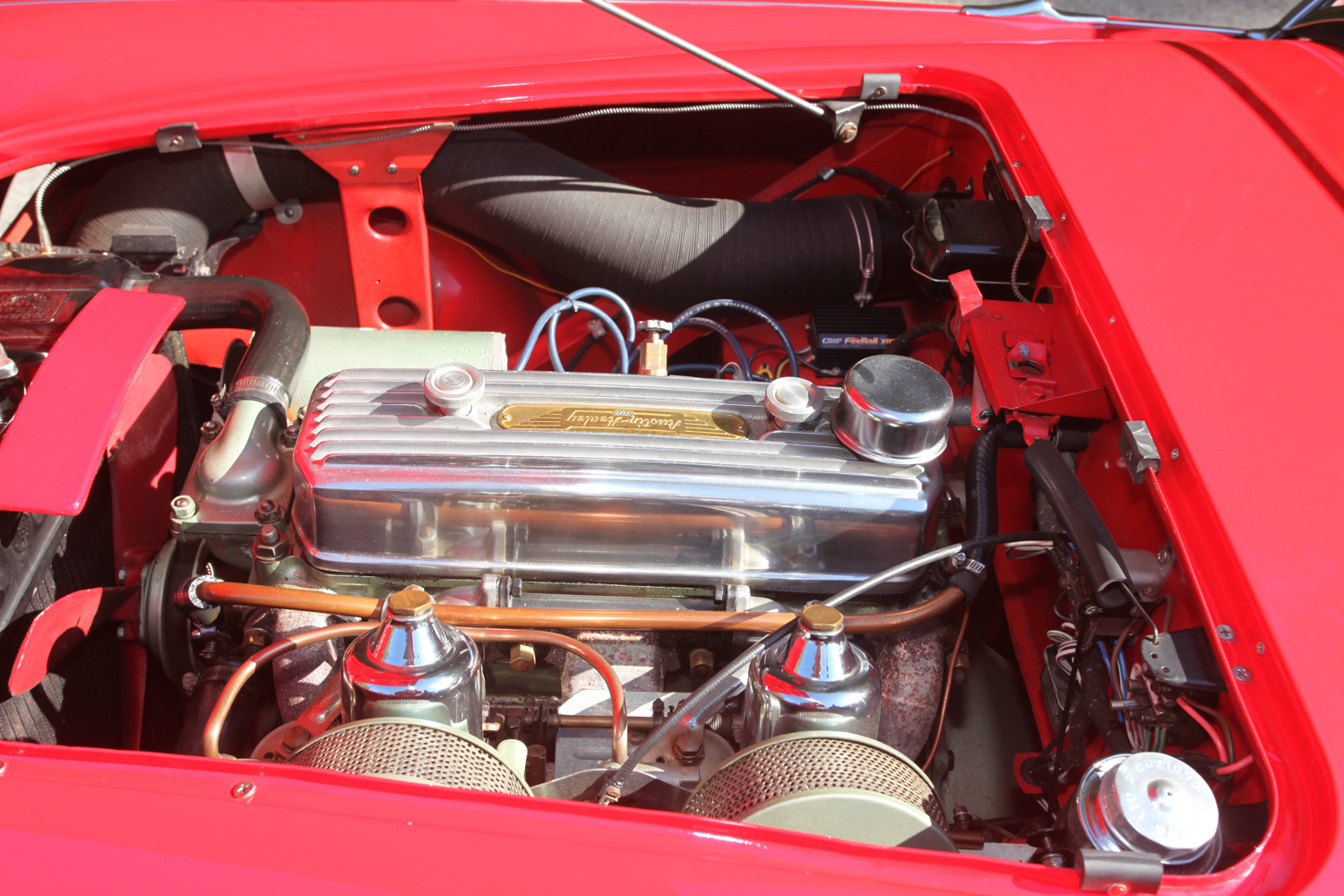

One day, a friend called to tell Warner about the two Healeys in Richmond, Indiana. It was winter with snow on the ground. The cars had been sitting for 28 years inside an old cinder block building that was surrounded by weeds. When Warner got in to inspect the cars and opened the trunk, a raccoon jumped out – it had a nest inside the trunk. Warner paid $2500 for the two cars and hauled them home. One of the cars was a complete, early car. The car that would ultimately belong to Warner’s son, Jeff, was a bit of a challenge. All four wheels were locked up, so Warner had to break them loose to move the car. The engine was on the floor with a carpet over it. It had been rebuilt but then just sat with no oil in it. The frame of the car was excellent, but all four fenders were rusted beyond saving. Thankfully, Warner had made a lot of friends when he was doing restorations, and a friend in Canada was making fenders for early Healeys. The engine condition turned out to be a pleasant surprise. Warner took it apart and checked it. It was in good condition, so he reassembled it, put it on a test stand, and ran it for ten hours. The only issue was an incorrect throw-out bearing. The car even came with a new differential.

Some parts were missing, so Warner had to search for some things, like the bumpers. The Eastern Fall Meet of the Antique Automobile Club of America in Hershey, Pennsylvania, proved to be a great place to find the missing pieces. When he put the car back together, he added an electronic ignition system, electric fan, and electric fuel pump. He also put disc brakes on the front of the car, so it became a bit like a 100S, which had discs all around. Warner found he could do a restoration in about a year, and that’s what it took to finish this car, and it is a very fine car.

“Driving Impressions”

Actually doing driving impressions during the pandemic was not a great idea, so it was necessary to find what others thought about the cars that are profiled. This Youtube video takes us on a nice ride in a Healey BN2:

According to The Motor: “There may be plenty of varieties to choose from, but whichever big Healey you opt for there’ll be no shortage of grunt. . . . Make no mistake, it’s a heavy vintage drive much like a Morgan although fitting an aftermarket power steering does make the car more manageable. Comparing it to an XK Jaguar is obvious; the Coventry cat is smoother although like the Healey, demands effort. Handling can be tail happy in the A-H, especially in the wet but with that big heavy old lump of an engine up front, it will understeer in normal use. . . . When The Motor first tested a Healey 100 in September 1953, it was clear that this was going to become a hugely sought after car. Not only was the performance sparkling but the value was exceptional. Having announced that the Healey 100 would cost £850 at launch, its metamorphosis into the Austin-Healey 100 lopped £100 off the asking price. . . . Singled out for particular praise were the engine’s flexibility along with its economy, which worked out at 22.5mpg over 871 miles of driving – no doubt much of which was rather spirited. Also appreciated were the supportive seats and the suspension settings, which reduced roll without producing a harsh ride – while the steering was ‘exceedingly good’. . . .

It was clear there was little to criticise; Motor reckoned there was too much engine heat escaping into the cabin and it was rather fiddly assembling the roof and sidescreens – but once in place they were effective. An interesting sign of the times was the fact that ‘one restriction on the car tested was the inability to make any kind of signal with the hood and sidescreens up. Flashing light direction indicators are however available if required’. What hadn’t changed was the effortless performance, only now there was an extra dose of smoothness too – or as the weekly put it: ‘this is an exceptionally enjoyable and untiring car fully deserving of the title Grand Tourer’. The magazine continued: ‘Reinforcing the comfort provided by the seats is a suspension system which secures exceptionally good results from a perfectly orthodox layout… This car gives a considerably more comfortable ride over bad surfaces than do most family saloons’. . . . Having singled out the seat comfort for particular praise, the summary ran: ‘A little attention to seating comfort and a few modifications to some of the minor controls would still further improve a car which now offers quite extraordinary performance in relation to its cost, taking performance in its broadest sense to include acceleration, maximum speed, roadholding and braking. The winning of the team award, amongst other striking successes, in the recent Alpine Rally, shows that durability is another attribute that must be added to the list’.” It is obvious that The Motor liked the Austin-Healey, and I think there are many Healey enthusiasts who would agree.

1956-1967

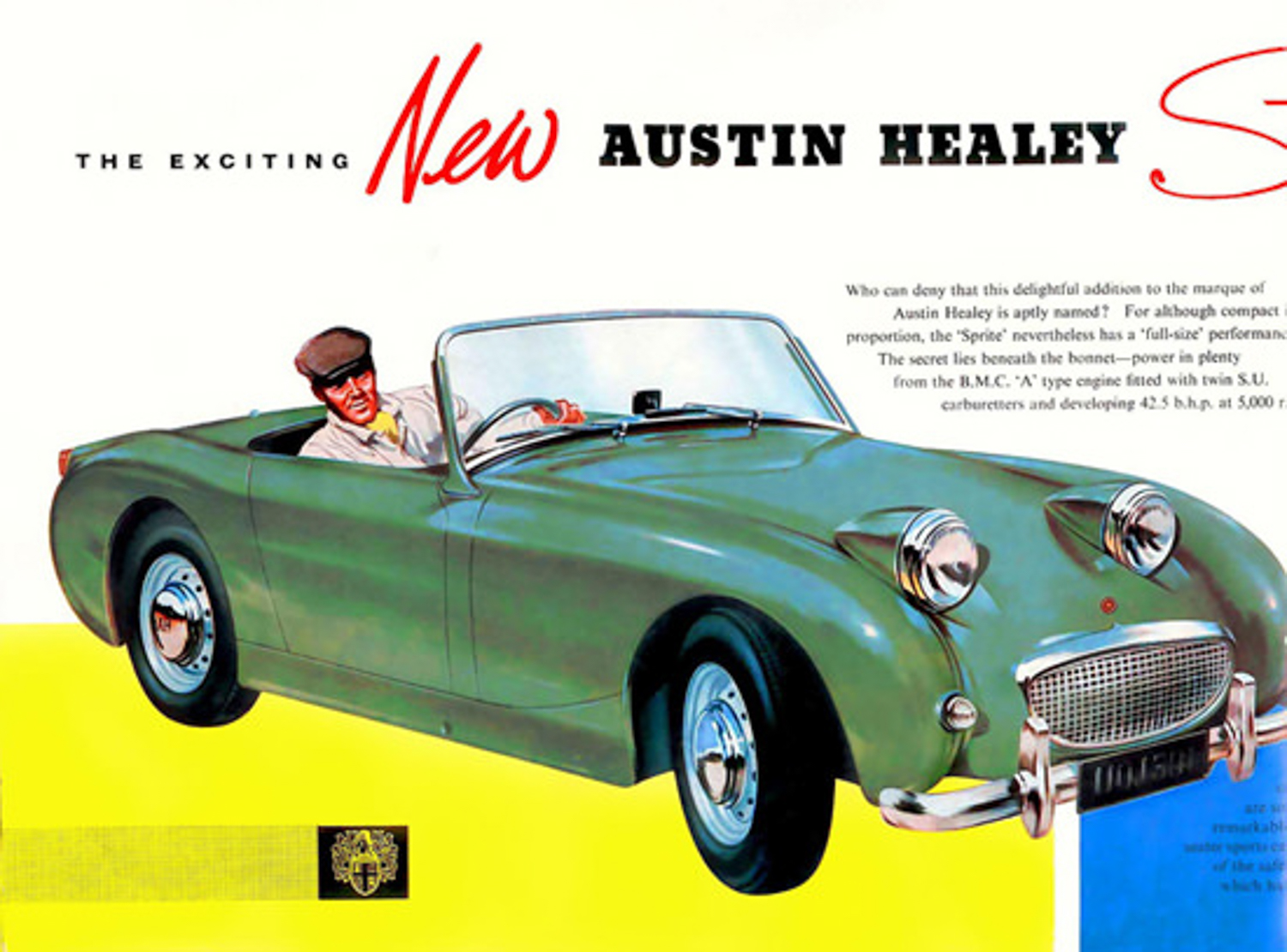

Donald Healey continued the development of the 100/6, improving both the braking and carburetion systems. Carburetion system issues, which required a rich mixture, were not solved until the introduction of the 3000 in 1959. That new 2912-cc engine also solved a top gear performance issue. About the time that the 100/6 was introduced, Lord suggested to Donald Healey that there was a need for a small sports car. Healey came up with some ideas, which Coker put to paper. The result was the Austin-Healey Sprite, often referred to as the “Bugeye” or “Frogeye” Sprite because of the fixed headlights that sat high on the bonnet, where there would have been pop-up headlights except for the cost. Improvements continued to be made on the 3000 and MKII Sprite/MG Midget until 1967 when the British Leyland Motor Corporation was founded and the 3000 was dropped and 1971 for the Sprite/Midget when the contract with Healey expired.

Donald and Geoff Healey weren’t done, though. They had ideas for a new sports car, and Kjell Qvale was interested. As the new owner of Jensen, Qvale got together with the Healeys, and the Jensen Healey was the result. In 1972, the new car was released, powered by a Lotus engine. Donald Healey was not happy with the result and that many decisions had been made without his input, so he resigned as Chair of Jensen Motor Company. Production ended in 1976, when the Jensen Motor Company collapsed.

Historians still hold the Healeys and the cars they produced in high regard. Mike Taylor and Julie M. Fenster, together with Donald Healey, wrote an article titled “Donald Healey: His Own Way” for the Fourth Quarter 1986 Automobile Quarterly (Volum XXIV, #4). They end their article with this: “The rally hero of pre-war Britain became the survivor of modern, oligarchic British Automaking: One man, rugged and graceful, and cars the way he saw them. The Austin-Healey is irreplaceable the way that a conglomerate is not, the way that a man is.” A tribute well earned.

Specifications

| Length | 3850mm (12’ 7.5”) |

| Width | 1590mm (5’ 0.5”) |

| Height (top up) | 1230mm (4’ 0.25”) |

| Wheelbase | 2290mm (7’ 6”) |

| Front Track | 1240mm (4’ 1”) |

| Rear Track | 1290mm (4’ 2.75”) |

| Ground Clearance | 140mm (5.5”) |

| Weight | 987 kg (2176 lbs) |

| Engine | Cast iron in-line, push-rod operated overhead valve four-cylinder |

| Displacement | 2660cc/162.3 cid |

| Bore/Stroke | 87.3 mm (3.438 in)/111.1 mm (4.375 in) |

| Compression ratio | 7.5:1 |

| Maximum Power | 90 bhp at 4000 rpm |

| Maximum Torque | 150 lb ft at 2000 rpm |

| Ignition | Lucas coil, 12 volt |

| Induction | Twin SU 1.5 in H4 Type |

| Transmission | Four-speed BMC C-series gearbox, three top gears synchronized, with Laycock de Normanville overdrive operating on top two gears |

| Front Brakes | Girling drums, 11 in x 1.75 in, two leading shoes |

| Rear Brakes | Girling drums, 11 in x 1.75 in, single leading shoe |

| Steering | Burman cam-and-peg |

| Front Suspension | Independent double wishbones, coil springs, double-acting lever-arm shocks, and anti-roll bar |

| Rear Suspension | Semi-elliptic springs with live rear axle, double-acting lever-arm shocks, transverse Panhard rod |

| Wheels | 5Jx15 in Dunlop wire 48-spoke knock-off wheels |

| Tires | Dunlop 590×15 Roadspeed tubed cross-ply tires |