1964 Lotus 30

Racing car enthusiasts, on the whole, treasure every innovative idea manufacturers have managed to conjure up. However, Auto Union and Porsche were criticized for putting the engine in the wrong place. When Ferrari eventually got round to doing the same thing, they got taken to task as well. The Formula One boys tried four-wheel-drive and everyone laughed, and when Ken Tyrrell went to six wheels, well you could hear the collective jaws hitting the floor. There have always been skeptics, pessimists and naysayers.

But when it comes to cars getting a “bad reputation,” there are a few classics. The ATS F1 car is one of them. A seeming disaster in period, it is a car that has seen continued development in historic racing and is now a very nice car. The Scirocco of the same period has had a similar experience. However, there are few cars that have received a worse reputation than Colin Chapman’s first foray into big-engined sports cars, the Lotus 30. If you said Lotus 30 to a race follower in the ’60s, ’70s or even later, you might well be greeted with guffaws, and if you dared to mention the later Lotus 40, you got ten more.

But why? And was it in any way justified?

Lotus in the mid-Sixties

The Lotus 30 design and construction had flaws, no doubt about it. These were, however, as much due to Lotus’s success, believe it or not, as to Colin Chapman’s sometimes single-minded approach to design or any inherent flaw. And the criticism of the Lotus 30, in period and subsequently, tends to overlook just what it did manage to achieve. As far as I can determine, its true potential has been recognized by very few indeed. I will attempt to convince you that the Lotus 30 had every bit as much potential as the early McLaren and Lola, never mind the lesser-known cars that rose and declined in the 1960s in the course of one season.

In 1963, Lotus, still in Cheshunt, Hertfordshire, had been having a very successful time. It had done very well, winning the World Championship. By year’s end, Lotus Elan production was working smoothly, as was production of the Lotus Cortina. In 15 years, the company had grown from three employees to 350 and all were very busy. Pressures were building to get ready for the Grand Prix season in 1964. The Indycar team had enormous responsibilities, and early in the new year they were already falling behind. Lotus was involved in so many racing categories, even the large staff could not keep up. It was at this point that Chapman decided to launch an attack on an increasingly popular category of sports car racing, that for Group 7 cars with large-displacement American-based engines.

Historically, criticism of the Lotus 30 tends to limit itself to a kind of general dismissal of the whole project as a bad idea, with allusions to poor results and a less than well-thought-out design. In practical terms, Chapman probably chose the wrong moment to take on a new and demanding project. That was the way he did things, however, and it was neither new to him nor a style limited to him alone. With Lotus’ relationship with Ford, it was natural to go for a Ford engine to power a challenger in this exciting and publicity-oriented category. There then was probably some logic in the car being looked after by the Indycar team with its familiarity with Ford power. However, Ford itself did not come on board with finance for the project, so both the work and the money came from the Indycar resources. That just put more pressure on a small team, and reduced the chances of proper development.

The design plan was novel. Chapman chose to use what Anthony Pritchard described as “a backbone-type chassis broadly similar in shape to that used for the Lotus Elan and inspired by its design.” Andrew Ferguson is blunter when he says it combined the “backbone chassis of the Elan and a big-banger American Ford V-8 engine.” Many saw this as a fundamental error, believing such a chassis could never cope with the stresses created by a big V-8. Mike Costin warned Chapman that that style of chassis would not cope with the intended use of 20-gauge steel. The problem would be in the fork-shaped engine bay where the designed-in channel section opened up to house the engine. In the prototype, Chapman took Costin’s advice and boxed in the channel legs for strength but did not reinforce the ‘kink’ where the chassis opens up. As a result the prototype twisted seriously in first engine tests, was thrown away and the unit was rebuilt with 16-gauge steel.

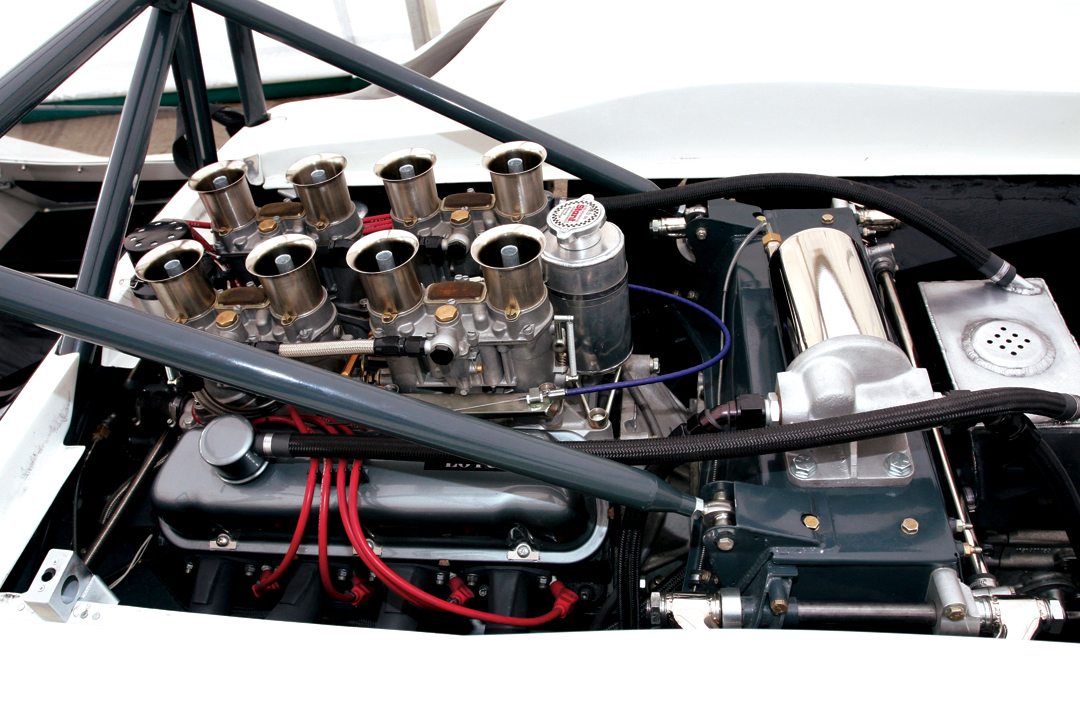

Costin was critical of the single-piece bodywork which made the car difficult to work on, but everyone agreed it had a beautiful and effective-looking shape. Costin also took issue with Chapman’s use of F1 wheels and brakes on a machine that weighed double the F1 car, and with an enveloping body there was the problem of cooling those brakes. Though Len Terry was nominally responsible for much of the Lotus 30 design work, it seems Colin called most of the shots, and by then Terry was just finishing out his contract with Lotus.

The car has a transverse box section at the front to carry the suspension, with two diverging arms at the rear forming a Y-shape where the engine is installed. The deep box-section backbone member incorporated a 30-gallon fuel tank, and additional tanks would fit in the sills of the bodywork. Unequal length double wishbones were used for the front suspension with combined coil spring/damper units. A somewhat complex set of upper wishbones, reversed lower wishbones and lower radius rods passing through slots in the arms of the backbone were used in the rear, with coil spring/damper units. Lotus bought 271 bhp V-8 engines from Ford to which four Weber carbs were fitted, yielding 350 bhp. This was mated to a 5-speed ZF gearbox. Much to the mechanics’ chagrin, in order to change the ratios, it was necessary to take the rear suspension apart. Twin radiators sat in the nose and there were 13-inch Indy-type four-spoke wheels, with Girling 11-inch disc brakes.

The 30 goes racing

The Lotus 30 was introduced at the Racing Car Show in London in January 1964. It was around this time that Andrew Ferguson had developed a new operational structure for the Lotus competition operations. This had been prompted by Ford’s desire to promote the Lotus Cortina in America. Ferguson’s new structure saw Team Lotus in six sections: Team Lotus F1; Team Lotus with Ford America (Indycars and big sports cars); Team Lotus Racing with Ford of Britain; Team Lotus Racing with EFLO (English Ford Line Organisation), and a racing Elan development team. There was also the Ron Harris-Team Lotus operation to run the F2 section, and the Ian Walker-Team Lotus group to run the Lotus 30 and Elan.

The Ian Walker team ran what is described by some as a “semi-works” car for Jim Clark at Aintree, whereas others view this as a straightforward works effort given the new team structure. Nevertheless, Clark finished 2nd on the Lotus 30’s debut. The car didn’t race at the Silverstone International Trophy meeting after fuel injection problems in practice. Clark then took the Lotus 30’s first win at Mallory Park’s Guards Trophy meeting a few weeks later. The late Trevor Taylor then had difficulties with the car at the Silverstone Martini meeting. He told the author that he sometimes thought the Lotus 30 was trying to kill him, but qualified that by saying that for a car which had not had much development, it was very quick. Clark had a water hose come off at the Brands Hatch Guards International, and finished 12th in the Tourist Trophy at Goodwood. He had, in fact, been leading when brake and suspension problems intervened. It is interesting that author Anthony Pritchard considers the Lotus 30 to have been a “disaster” and 1964 a year of “very little success.” This is in spite of the fact that 21 cars were sold during that first year. Clark had also been very impressive at Riverside late in 1964, driving with great flair and finishing 3rd overall on the high-speed California track.

The chassis had been made more rigid after the first three cars had been built. For 1965, the Series II Lotus 30 appeared. The new car had a number of changes, including a detachable center section to the bridge carrying the rear suspension. Twelve Series II cars would be produced. Clark took a win early in the season at the Senior Service 200 race at Silverstone in March. He won again on Easter Monday at Goodwood with victory in the Glover Trophy. Though the various Team Lotus commitments were distracting from development, the Lotus 30 still looked capable of performing against the McLaren-Oldsmobile and the Lola-Chevy, and certainly at Goodwood they could not match Clark’s pace.

Clark failed to finish at the Oulton Park Gold Cup when the gearbox broke, and Jack Sears took 3rd in the International Trophy event at Silverstone, which was the end of a works effort with the car. At Oulton Park, the Clark car had a 5.3-liter engine installed, a pattern that was then followed by many teams. Three Lotus 40 models were built in ’65-’66, but by then Chapman and Lotus had too many other things going on and that was the end of the Lotus “big-banger.” Clark, most closely associated with the Lotus 30, was sometimes given as an example of how poor the car was, Eric Dymock saying he was too polite to say to Chapman how bad it was. On the other hand, Jimmy always got on with the job, and in fact could make the car go very quickly. He had three wins and three more top-three finishes in only nine races that he did in the Lotus 30. He even called it a “nice and forgiving car to drive,” so his relative silence about the car can hardly be used against it!

Chassis 30/L/20…the David Prophet car

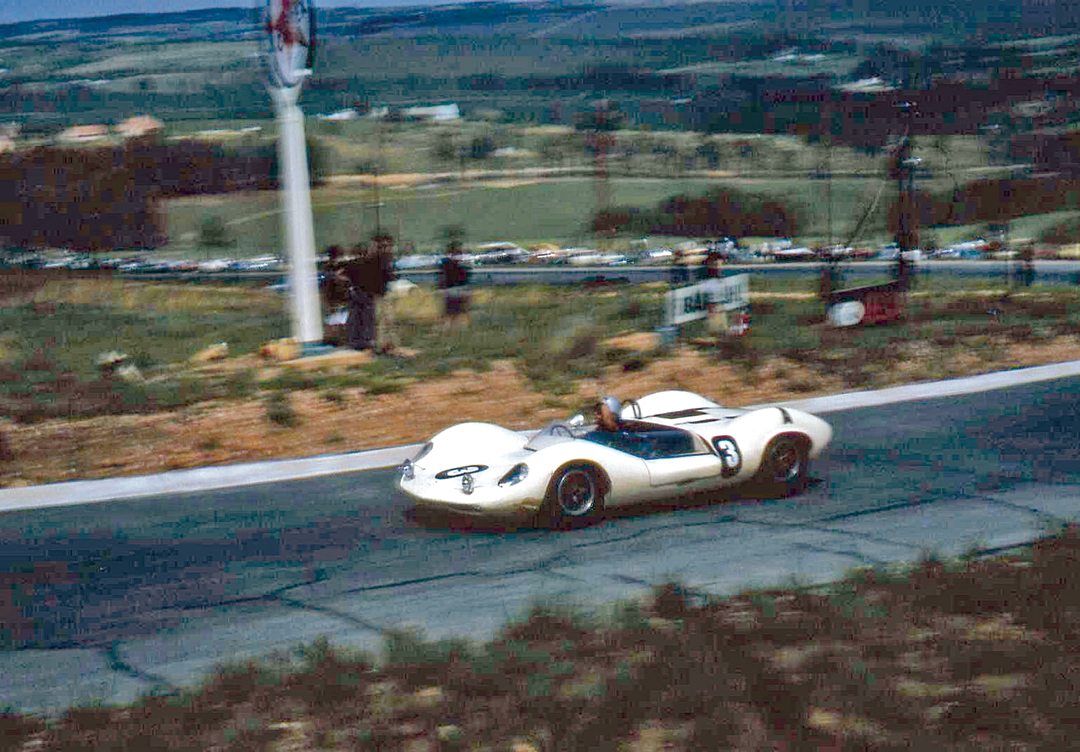

Privateer David Prophet bought chassis 30/L/11 late in 1964 and took it to South Africa for a series of races. On November 1 it was co-driven by Prophet and Brausch Neimann in the Kyalami Nine Hours where it was running very well until a number of minor ills led to its retirement. This was followed by a fairly sensational outright victory in the Rhodesian Grand Prix on November 29, a very auspicious start for the car. The car would seem to have taken something of a hammering in the South African races it did and thus the chassis was replaced with chassis 30/L/20 when it returned to England in 1965, and it has retained this identity to the present.

Prophet then did six races before selling it to Gerry Ashmore. These included the Senior Service 200 at Silverstone on March 20. On May 1, it was 9th in Heat One and 12th in Heat Two for 10th overall in the Tourist Trophy at Oulton Park. It was back at Silverstone on May 15, at Mallory Park for the Guards Trophy on June 7, and finished a very good 4th at the British Grand Prix meeting on July 10. It followed this with 5th in the Martini Trophy race at Silverstone on July 24. It was sold to Ashmore in August, and he raced it at Brands Hatch in the Guards Trophy. He did three further races in 1966 before it was sold, converted for road use with a coupe body (!), and then it moved to the USA where it eventually languished for many years before coming back to Matthew Watts in the UK five years ago. It returned as a rolling chassis. It is important to note, that in the 1965 period, it gained the nose and tail fins and air dams that it sports today. Following its recent appearance at the Goodwood Revival, a number of “non-experts” swore blind these cars never had such attachments in period, which is wrong. Some protestors displayed photos of Clark in the very early car as “evidence” and, of course, the very early works cars didn’t have the spoilers.

Restoring a Lotus 30

Matthew Watts is very much of the view that the Lotus 30 was much maligned and a number of myths grew around it, but essentially the problems were related to Lotus not having the time in period to develop it. Hence his aim was to do some of this delayed refinement. Howard Redhouse also owns a Lotus 30, and he and Matthew are very much in agreement about the unjust reputation the car seems to have gained. Redhouse ran his car in the Tour Britannia a few years ago and surprised many people with its versatility.

This car came to Matthew from the USA as a rolling chassis. A full restoration was carried out, removing the coupe bodywork and fitting the original-spec body. The chassis had a large number of original parts, but was in a relatively rough state and some sections needed to be replaced. A lot of attention was paid to the wishbones, which were grossly under strength, so purely on a safety basis a number of wishbones were “beefed up.” It seems very likely that the wishbones were flexing in period and that many of the drivers thought it was the chassis flexing, so the unusual chassis often got the blame. It could well have been a combination of other things as well. Jim Clark often drove the car very quickly, and his ability to drive around handling difficulties both showed the potential of the car and strangely confirmed for critics it had a “chassis problem” and only Clark’s skill could make the car go quickly. His lap time at Goodwood in the Lotus 30 still stands as a target for Lola T70s and the like.

A great deal of thought was given to making improvements to the car during restoration, but doing this within the regulations of the original period. So, spring rates, damper valving, anti-roll bar diameters, and the front to rear balance came in for some scrutiny. It was indeed going to be very interesting to join Matthew Watts in the first serious test of the car at Silverstone. Could we re-write history?

Driving chassis 30/L/20

Our very much anticipated test at Silverstone was scheduled not long after the Lotus Festival at Snetterton, and I told Clive Chapman, son of the late Colin, what I was going to do. He was very quick to respond, saying how badly he felt that history—and journalists—had treated the car:

“The Team Lotus Type 30 is a beautiful, dramatic and successful racing car. The sweeping lines are stunning, especially without the spoilers that were eventually added to all sports prototypes of the period. The noise is spectacular and the handling makes for a real challenge. In period, Team Lotus raced the car at ten events in 1964 and 1965, winning three times. The Type 30 has suffered somewhat by comparison to its stable mates, but it was a different animal, being a car that relied on a massive engine for its performance. Therefore, relatively speaking, the car was a handful, and not in keeping with the lightweight and quick-round-corners characteristics of other Team Lotus designs. As a result, people could not wait to criticize the car, and still do to this day; it is an easy target. Relative to the opposition, if not its stable mates, the Type 30 was successful in period and has now proved popular in historic racing. Anyone who takes on the challenge has to endure a steady stream of throwaway derogatory remarks, but those who have risen above this have experienced the thrill of driving a famous Lotus, and have proved to be competitive among contemporaries.”

Matthew Watts has risen to the challenge, and just before we changed places so I could get behind the wheel, he reported his first impressions. At this early stage of sorting, he felt the car was very sure-footed, its platform suiting the very powerful V-8 engine, which is now 5.3 liters as was the works car of Jim Clark in 1965. He thought it was nothing like an “overgrown twin-cam Lotus 23 sort of car.” He found the braking to be very good, the benefit of this car being the first to use Ford Thunderbird-derived ventilated disc brakes. As I started up the rumbling V-8—a unit with stunningly impressive sound at all revs—Matthew was working out how the fine balance of the car could be improved.

I was very interested in what my first sample of the handling would be like. The 30 was immediately impressive as being quite stiff and firm, and there was no roll or pitch in the corners. This was at least partly due to Matthew’s attention to the suspension, but the car is very neatly laid out, all part of the original design. There were several things to get used to. One was the amazing original four-spoke steering wheel in your hands, and another the effort it takes to see where the apex of each corner is. The body is beautiful, but it takes an effort to see over the wheel bulges. In fact, you have to know where the apex is rather than depend on seeing it. As the power is so smooth and manageable from the noisy Ford engine, it doesn’t take long to do that. Everything is progressive, and power comes on smoothly in every gear.

It took a bit of work in the pit lane to find first gear, but after that, the gearbox was easy to manage. As it is a ZF box, that means you have to change gears up and down progressively, no skipping gears, and again, that wasn’t a chore. The clutch was civilized, and the torque was not only apparent but the power was transmitted to the road with plenty of feel and without the kind of difficulties some of the early critics always said would appear when you put the throttle down hard. As we were using what is now called the “old” Grand Prix circuit at Silverstone, there was plenty of opportunity to sample slow, medium and fast corners. While not quite at full speed, the Lotus 30 was indeed “sure-footed,” especially important as you head down the Hangar Straight and decide not to brake for Stowe. A glance at the rev counter, red-lined at 6600 rpm, showed about 5500 at this point, so much more was yet to come.

Perhaps the most scintillating performance came from the exit of Vale in second, up through third, fourth, and fifth and then down again—fourth, third, second—through the chicane and hard acceleration up through the box and turn into Bridge Corner. The noise and heat from the big lump behind you was pretty spectacular on all the straight bits too. The power comes on at about 3000 rpm. You can watch the rev-counter, but you can tell what the Ford engine is doing simply by listening! The tires worked well all the time—Dunlop Racing 5.50M-15 on the front and 6.50-15 on the back, all on beautiful knock-off wheels.

Summing it up

The Lotus 30 is now up for sale, if Matt can bring himself to part with it. I hope it doesn’t go before I get another run; I would really like one more taste of a racecar that clearly had vast potential in period, had some great results, was driven by great drivers, and now, 46 years later, is superbly quick and reliable. Chasing round Goodwood—with the spirit of Jim Clark not far away—what a sight to see.

Someone else is in for the treat of a lifetime.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: Girder box section center backbone with rear transverse box section

Front suspension: Unequal length double wishbones and coil/spring dampers

Rear suspension: Upper wishbones, lower reversed wishbones, lower radius rods and coil/spring dampers

Wheelbase: 7 feet 10.5 inches

Track: 4 feet 5 inches front and rear

Length: 13 feet 9 inches

Weight: 13.66 cwt. / 1530 lbs

Engine: Ford V-8 originally 4727-cc pushrod ohv, now 5300-cc

Power: Originally 350 bhp @ 5750 rpm, now 450 bhp @ 6600

Gearbox: ZF combined 5-speed, all synchromesh box and final drive

Resources

Many thanks to Matthew Watts (www.retro trackandair.aol.com) for all his help, to Ted “The Ferret” Walker for helping to arrange the test, and to Clive Chapman of Classic Team Lotus.

Dymock, E. Jim Clark – Racing Legend

Motorbooks International, Minnesota USA 2003

Ferguson, A. Team Lotus: The Indianapolis Years Patrick Stephens Ltd. Northants UK 1996

Pritchard, A. Lotus – All The Cars Aston Publications Bucks, UK 1992