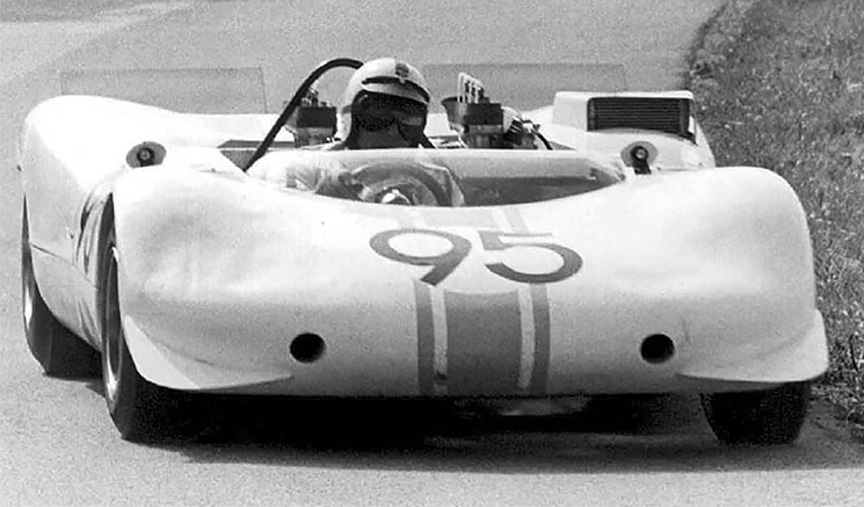

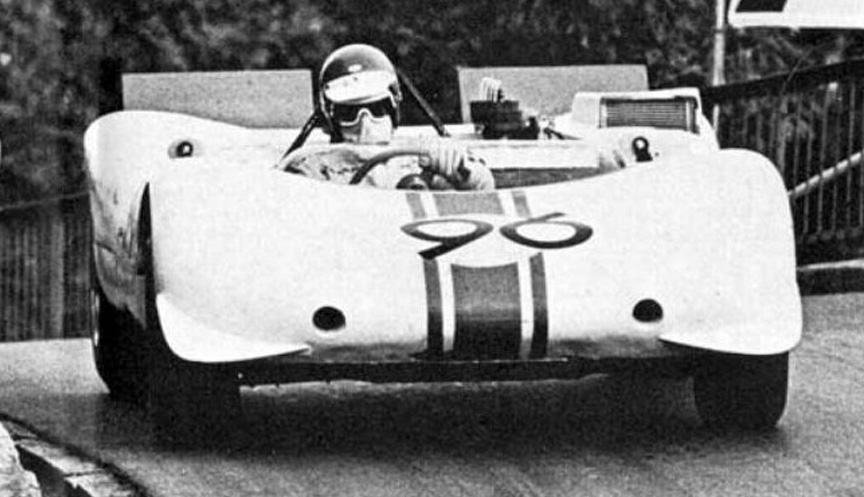

1968 Porsche 909 Bergspyder

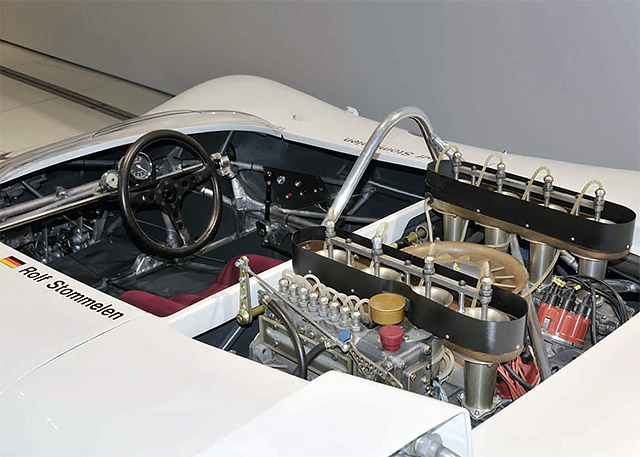

Year: 1968 / Engine: 2.0 L Type 771 flat-eight / Power: 275 hp / Weight: 385 kg (849 lb)

In the 1960s hillclimbing was a big focus for automotive manufacturers and they would spend big money and goto extreme lengths to have the quickest cars racing up the hill. For Porsche this meant building the remarkable 909 Bergspyder.

Supercars.net readers know their super cars and Porsche models but it’s possible many of our readers have never heard of the Porsche 909 Bergspyder and that is not super surprising. Built specifically for hillclimbing, the stop-gap race car may have had a short life, but it was a technical marvel that represented a watershed for Porsche, an object lesson in weight-saving like had never been seen before. At the time the 909 Bergspyder was claimed to be the most uncompromised racer Porsche had ever built and none had a greater singularity of purpose.

The 909 Bergspyder did not win a major event. It ended up being an awesome laboratory of ideas (not all worked). Thanks to timing and regulation changes that got rid of the minimum weight requirement and an ongoing battle between Ferrari and Porsche, these ideas also cemented the rise of Ferdinand Piëch as an original thinker and brilliant leader.

Porsche and Hillclimbs

The pinnacle for hillclimb racing was the mid-1960s. In fact, during the 1950s and ‘60s, the sport of hillclimbing was so high profile that carmakers built dedicated machines and paid professional drivers to race them. The world’s best race teams took it as seriously as Formula One is taken today.

Porsche competed as a factory in these hill climb events until the late 1960s. Porsche’s motorsports boss Ferdinand Piëch believed the tight, twisting roads and high-altitude nature of the locations helped Porsche engineers learn how to prioritize ride and handling and was the ultimate proving ground for engineering innovation.

Porsche was dominant too. In the 24 trophy-eligible European Hillclimb Championship classes from 1958-1968, Porsche won 20 of them outright. Porsche regularly scored at least one class victory per year in hillclimb events. Cars such as the Porsche 718 R860 Spyder and the 356B 2000 GS Carrera GTL were legendary in this era.

Beating Ferrari

Porsche had a serious rivalry with Ferrari and its star driver, Ludovico Scarfiotti. This competition and drive to win led to the rapid development of racing car technology of the kind never before seen. 1968 was the peak.

Porsche won the European Hillclimb Championship in 1967, and Enzo sanctioned the build of a completely new, lightweight hill climbing focused website.

Ferdinand Piëch, on hearing that Ferrari had a new, improved 212E in the pipeline and with a strong motorsport budget and board behind him, immediately tasked his team to build a brand-new car to counter the Ferrari threat. It was to be a superlight rolling laboratory with which to experiment and showcase his and senior race engineer Peter Falk’s more outlandish ideas. It was a time of creative and extraordinary engineering thinking.

A Primer – Porsche 910/8 Bergspyder

In 1967 and 1968, the Porsche 910/8 Bergspyder was the dominant force before the 909 came along. Porsche’s 910 was essentially an updated 906 and were championship-winning machines thanks to being extremely nimble and well-suited to mountain roads.

Technically it was state-of-the-art, featuring materials such as titanium (brake calipers), beryllium (brake discs), magnesium (wheels), electron (tank), plastic (body) and aluminium. The running gear was similar to that of a Formula 1 car, including an eight-cylinder boxer engine that had about 275 horsepower.

The European Hillclimb Championship regulations stipulated 2-liter engine but didn’t stipulate minimum weight. The 910/8 initially weighed just under 990 pounds (450 kg) but by 1968, with additional development and optimization it weighed in at just 930 pounds (420 kg).

It wasn’t enough for Ferdinand Piëch who ordered the brand-new hillclimb car, lighter even than the bantamweight 910.

Extreme Weight Saving

The European Hillclimb Championship rulebook was light on restrictions, but one regulation was sacrosanct: engine capacity. All engines were limited to two liters, but crucially there was no minimum weight. That was the focus for Porsche and they took weight-saving to the absolute extreme.

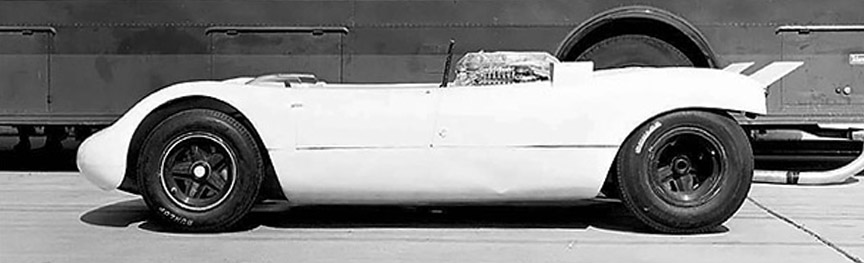

At 849 pounds (385 kg) it was the lightest racing car Porsche has ever built. How is it possible that chassis, engine, gearbox, brakes, suspension, bodywork, wheels, tires and ancillaries could all weigh under 400 kg? For comparison, a modern Formula One car weighs 1500 pounds (691 kg), a front-running Le Mans racer no less than 2000 pounds (900 kg). The result was a power-to-weight ratio of 714 hp/ton (36 hp/ton less than the Bugatti Chiron with a fifth power).

The 909 Bergspyder was based on the 910, but Piëch had tasked his team of engineers, including the legendary Peter Falk, to remove weight on every component.

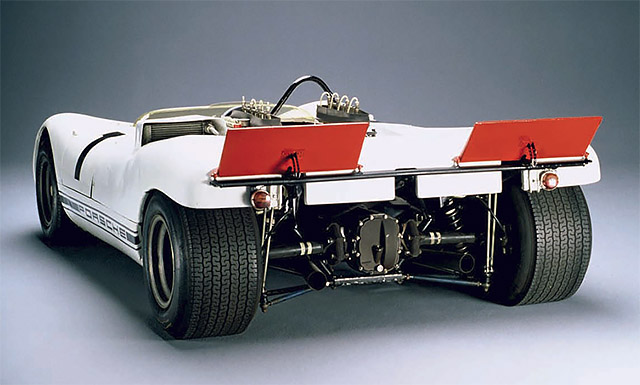

Piëch had encouraged his engineers to use magnesium engine casings and aluminum chassis tubing. This spidery lattice of aluminium tubes was light but not super strong. The bodywork was a single skin of fiberglass with paint so thin you could see the sun shining through it.

Beryllium was chosen for the brake discs (actually first trialled on the 910), saving 25% off an equivalent brake disc and around 28 pounds of unsprung weight. Beryllium is strong, incredibly light and possesses thermal properties perfect for what Porsche had in mind for it. It only had two drawbacks, by far the smaller of the two was it was spectacularly expensive – a five figure sum per disc in today’s terms. Rather more inconvenient was the fact it came with a chance of killing you. Like other metals used as braking materials, beryllium discs give off dust under heavy use. Unlike other metals however, if you are exposed to sufficient quantities of beryllium dust, it can have life-compromising or even life-terminating pulmonary consequences. Which is why it is now labelled as a category one carcinogen. Wow.

It was not the only exotic material used on the Bergspyder. The suspension springs were made from titanium, balsa wood ballast resistors were used for the ignition system and the wiring loom was made from silver because it was lighter than conventional copper. Piëch even invented a solution to remove the fuel pump by putting the fuel in a rubber bag and encasing that bag in a titanium tank that was then filled with pressurised nitrogen (thus forcing the fuel through to the engine and negating the need for the fuel pump).

Piëch encouraged his team of engineers to dispense with unnecessary parts, and with that, the alternator was shown the bin. A small battery provided enough spark for the car to climb a short hill. He wasn’t quite done, even then. Legend has it that during the development of the 909, Piëch would place a magnet on random parts of the car, and if it stuck he ordered engineers to find a lighter or thinner material.

More Technical Highlights

There wasn’t much that could be done about the engine, which had been conceived for the 1962 Porsche 804 F1 car. Porsche had already got as much power as was possible from its two-liters and done as much as it could to eliminate the need for ancillaries.

But not everything was about just saving weight. Porsche needed to get more weight over the front axle, so the engine and gearbox were moved far forward, aided by the groundbreaking (at the time) move of placing the differential behind the ’box. That allowed Porsche to put the major mass of the car almost at its very centre with front and rear balance provided by, respectively, the driver who sat so far forward the front suspension anti-roll bar passed above his thighs, and the five-speed gearbox.

Pushing everything so far forward not only centralised mass to improve weight distribution, but as the driver’s lower limbs simply stuck ever further out into the front overhang, the entire car could be abbreviated. The wheelbase and bodywork were just 3,447 mm long (basically 3 ft shorter than a new Cayman).

The shorter the wheelbase relative to the track, the less stable the car would be but that is precisely what Porsche wanted: stability is the enemy of agility and of all the tools you need on the hills, agility is the most important of all. So the company pumped out the track as far as it would go too.

There’s no real context that does the Bergspyder’s power-to-weight ratio justice. The 909 was nearly half the weight of a modern F1 car, lighter than some motorcycles, and 1/5 the weight of a Bugatti Veyron. The 909’s power-to-weight ratio was simply shattering and this ferocious beast could allegedly sprint to 100kmh in under 2.5 seconds.

Racing Results

Porsche built two 909s, campaigning them in 1968.

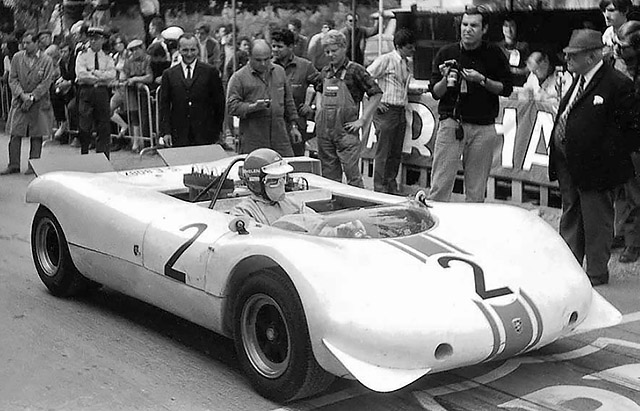

In theory it should have been unstoppable. Despite being launched in 1967 the much-feared Ferrari 212E Montagna the Bergspyder was designed to combat simply failed to materialise. But despite Mitter being amazed by the car in testing, at its hillclimb debut at Gaisberg on 8 September 1968, he chose instead to drive his old 910. This left the new Bergspyder to Rolf Stommelen. Stommelen was handed the task of competing with the 909 Bergspyder.

The conventional fuel tank and electric pump were done away with in favor of the nitrogen-pressurised titanium ball fuel setup. This doomed the car and didn’t really work as expected and caused running problems that blighted the entire weekend. The design failed several times because either a valve in the titanium ball failed or the rubber bladder stuck to itself and became impossible to fill.

Stommelen still raced the car in two competitive hillclimbs, finishing third and second. The third place happened at Gaisberg and the second place at Mont Ventoux. Stommelen called the 909 “lethal at high speeds” so maybe it is a good thing that things ended there. The 909’s rather uninspiring two races meant the end of the road for the racecar. With the championship under its belt, Porsche turned its focus towards endurance racing.

The 909 would be the company’s last dedicated hillclimb machine. Porsche did not enter the 1969 European Hillclimb Championship, preferring instead to stun the world with the 917. The 909 Bergspyder was never able to show its true potential. The Ferrari 212E Montagna turned up in 1969, entered nine of the ten championship rounds and won every race.