1959 Costin-Lister BHL133

When speaking to Brian Lister, some years ago, I asked him about the secret of his success. Just how did those Lister cars become world-beaters and icons of the era? Modestly, he replied, “My belief, in those days, was simplicity being the art of good construction, although today’s computer-aided design would challenge that belief.” He went on to admit that most of his designs for Lister cars came from the pre-war Mercedes racing cars—simplistic, tubular chassis, independent front suspension, de Dion rear suspension and at the hub, reliability. Core to that success was a diminutive, physically handicapped, but thoroughly talented driver, William Archibald “Archie” Scott Brown, admired by all—even the maestro, Fangio, was an admirer. The pair, Brian Lister and Archie Scott Brown, was inseparable and a dynamic force to be reckoned with, they were to motor racing like Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire to dancing. In the 1957 season, of the 14 races entered, there were 11 wins, two 2nd places and a single retirement, with multiple lap records broken either during practice or the race itself. As Brian said, “It wasn’t perfect, but it’s not a bad record for a racing car.” Indeed, this great, but humble, team tore down many records and were admired by many who, obviously, wished to emulate their success. However, much of that success was due to the humility, self-effacement and character in which the team was run, devoid of massive funding, glitzy advertising and general razzmatazz—purely a small group of enthusiastic men striving to win.

All good things must come to an end, and so it did. The month was May 1958. The race was the 10th running of the BRDC International Trophy at Silverstone on the third day of the month. American racer Masten Gregory, in an Ecurie Ecosse Lister Jaguar (BHL104), took the 25-lap sports car race by storm, leaving a mystified Archie Scott Brown in a distant 2nd place, some 30 seconds down. A puzzled Scott Brown couldn’t understand the chink in his armor, where had it all gone wrong? The following weekend found the Scott Brown/Lister Jaguar combination winning again at Mallory Park, but Gregory wasn’t at that event. Looking back there are so many drivers who died competing at an event they shouldn’t have been at, Scott Brown was due to run at Monte Carlo aboard Archie Butterworth’s Cooper, but it wasn’t ready. So, when his entry was accepted to run at Spa, Archie was delighted, not only was it an acknowledgement of acceptance by the Belgian racing authority in spite of his physical handicap, but an opportunity to engage again with Masten Gregory. Sir Stirling Moss once said, “To achieve anything in this game you must be prepared to dabble in the boundary of disaster.” With Gregory putting his Lister Jaguar on pole, Scott Brown knew the race and battle was truly on and his competitive nature would certainly allow him to “dabble” as remarked by Moss. Outside the car, and in the lead-up to that race, there were those who had certain premonitions that disaster could strike, including Brian Lister’s wife, Jose, who telephoned Archie telling him to take care, and team member Ken Hazelwood who believed the Spa race, in Archie’s mind, was a continuation of Silverstone just two weeks before. The flag fell and the race became a duel with Gregory and Scott Brown out front passing and re-passing each other. On lap six, Archie was leading, but as he approached Clubhouse Bend the road surface was damp as a result of one of the “usual local Spa showers,” but even drawing on his most dexterous driving style Scott Brown couldn’t hold the car. As it left the road, the car made contact with the Dick Seaman Memorial (Seaman had died at that same spot in 1939) and then a road sign, which bent the right-hand front suspension. By this time the car was completely out of control. Fuel gushed out as the car rolled, instantly igniting the lightweight magnesium body (immediately dispensed with following the accident). Badly burned, but still able to talk, Archie was rescued by a gendarme and taken to hospital. Some 24 hours later Archie Scott Brown died, just a handful of days following his 32nd birthday. There was no suggestion that foul play had anything to do with the crash, nor car defect, nor was it due to Archie Scott Brown’s physical limitations (he’d proved his ability time and again), nor Masten Gregory who was occasionally noted for his sometime erratic driving—none of the above, it was unquestionably just a motor racing accident. Had it happened on a British airfield circuit there would have been plenty of run-off, but this was the tight public road circuit of Spa-Francorchamps, its idiosyncratic weather conditions.

Just prior to his death, there are reports Archie told Brian Lister not to feel too bad about the crash. Clearly, Lister wanted to walk away from racing immediately, which was simply a natural reaction. Nevertheless, there was a team of men reliant on his continuing in the sport, there were customers who needed cars maintained, there were sponsors who’d invested money into the team for at least a season’s racing, so the thought of walking away was soon extinguished—but where would he go from here? What did the future hold for the little team from Cambridge?

Frank Costin

Brian Lister was conscious of the adage, “If you stand still in motor racing you go backward,” which still applies to the sport today—perhaps even more so. The 1958 Lister Jaguars were prone to lifting at high speed, something Ecurie Ecosse sorted by fairing the bodywork inward, a solution Lister copied. Streamlining became the latest design thinking, probably taken from the success of the Mercedes Grand Prix cars of 1954 and 1955. Enzo Ferrari scoffed at this: “Aerodynamics are for people who can’t build engines.” However, Colin Chapman had made use of the services of a certain aerodynamicist, Frank Costin. Costin, the older brother of Mike Costin (the “Cos” of Cosworth), had also worked for Vanwall (recommended to Tony Vandervell by Chapman) and had gained all his vast experience while working at de Havilland. So, Frank Costin became the obvious choice. His brief was to design a replacement for the much adored “knobbly,” which was becoming tired. There wasn’t too much time to build a complete new car at this point, but an interim car using the same chassis and engine layout with more streamlined bodywork would be a quick fix prior to the all-new car taking to the track. However, firstly, there was an Achilles’ heel on the 1958 Lister Jaguar, severe overheating at the rear. He worked on a periscope design fitted to the bodywork directly behind the passenger seat, acting as a cooling duct that scooped air and channelled it down toward the roasting diff and brakes.

Frank Costin’s full-time activities for Lister started toward the end of the 1958 season, around October time. Lister Chief Mechanic, Edwin “Dick” Barton, recalls him joining and his immediate effectiveness. Costin did a couple of things to assist with the current car, but his main influence was on the 1959 car. Where Brian Lister would work on a smaller and smaller frontal end, Frank worked with totally different thinking. He convinced Brian that a low frontal area wasn’t necessarily the right way to go, and the new more bulbous, aerodynamic design he had in mind was the best way forward. Barton continues, “I always thought that Frank Costin brought a technical sophistication, never seen before at Lister. I’ll give an example: when Norman Hillwood looked to fit a Jaguar engine into his Lister; Brian said the 16-gauge tubing wasn’t strong enough. I was sent to get some 3-inch, 14-gauge tubing as a replacement. When I got back to the factory, Brian stood each end of the tubing on two bricks. He asked four, or five of us to stand on the tubing and jump up and down to see how it stood up to our weight—that was Brian’s way of stress checking the material. Of course, Costin’s way was by mathematical and algebraic calculations more in tune with aircraft design. He showed us things we had no knowledge of in those days, like thermo-coupling, so we could check the relevant temperatures on a given component. Then there was temperature paint—we’d never heard of such stuff, it was a real education. On the 1959 car too, we’d have tufts of wool attached to the bodywork. I remember at Snetterton we’d run up the straight in a car taking photos of the new car, from the information gained on these photos precise alterations would be made to get the optimum shape. He also introduced a heat-sink mesh material to help cool the car—yet another innovation. We had moved up a gear or two.”

1959 Costin-Lister

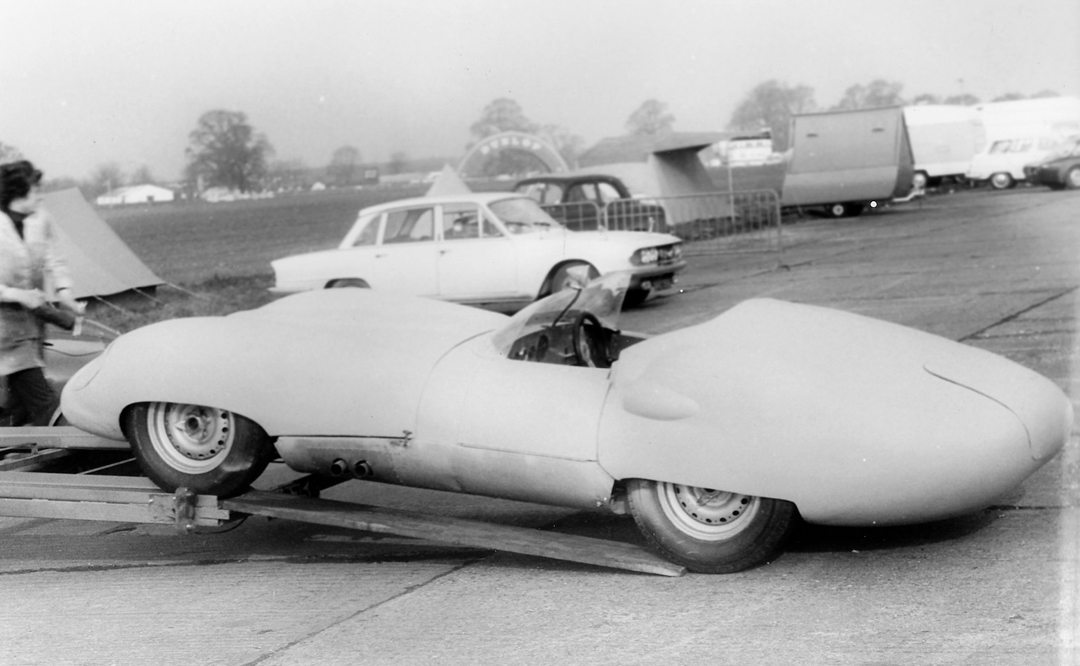

Brian Lister would concede many times to the thoughts and practices of Frank Costin, over the final design of the ’59 car, purely because of his technical prowess. It was in an effort for Lister to conquer Le Mans, if not for ’59, certainly 1960 when the space-framed car would be up and running. There were some who would say that Costin was a tad dogmatic—it was his way, or the highway, he always knew best. The final styling of the 1959 car took many concepts from Costin’s previous and reasonably successful work with Lotus and Vanwall. Williams & Pritchard were responsible for the new Lister bodywork and there were trying times working with the designer and his meticulous attention to detail. Starting from the rear, there was a high tail end that started where the all-enveloping curved windscreen finished, the driver looked to be totally cocooned, the windscreen itself curved in at the top, extending that slippery feel. The typically spacious cockpit was lushly finished with new Cox & Co (Watford) Limited designed seats, an extravagance to the norm. Also, more driver comfort was afforded by circulating air being available from slots let into the body under the screen. An innovative self-inflating, membrane tonneau cover was later added, smoothing airflow over the cockpit, but realistically was not as successful in practice as the hypothesis suggested. Gone were the “knobbly bits” of the ’58 car, replaced with a long nose section with a bulge in the middle to house the obstructing points of the Jaguar engine. Left and right, the two front fenders were cigar-shaped pontoons accommodating the front wheels and headlights The front was bulkier than Brian would have designed, supposedly to take advantage of the, theoretical at this stage, aerodynamic efficiency.

At its launch in January 1959, it was clear to see that Brian Lister wasn’t too convinced that Costin’s car would give the ultimate benefit all the reckonings suggested. There was one significant difference, which was cost. Of course, de Havilland, the designer’s former employer, had big budgets to work with and no one was really watching the pennies that much. The Lister approach was a more frugal outlook—spend a little, to gain a lot. That way had worked from the inception of the motor racing project until Costin arrived. The proof would be on track, while this more sophisticated, streamlined, all-enveloping, low-drag design worked significantly better according to the hundreds of theoretical calculations, and in Costin’s eyes looked very much the part, running in competition would be the ultimate test.

The Sebring 12 Hours was the opening race of the 1959 racing season and the ultimate acid test for this new iteration of Lister. Chassis BHL 123 was sold to the Momo Corporation/Briggs Cunningham with Stirling Moss and Ivor Bueb nominated to drive. Cunningham also entered two 1958 Lister cars, one for himself and Dick Thompson, and the other for Walt Hansgen and Lake Underwood to drive. Moss had tested the new “banana-shaped” car, as he described it at Silverstone prior to it being freighted to the U.S. In the test, Moss found it handled better with 40 pounds of pressure in the rear tires, as opposed to 35 pounds all round, and with a 3.7 axle saw 6,000 rpm on the straight and 6,100 rpm after Abbey Curve. The early assessments of both Moss and Bueb at Sebring agreed that the car was over-geared, so mechanics worked to rectify the issues for qualifying and the race. In the race, Ivor Bueb took the first stint and at the end of 2½ hours the car was 5th, some two laps shy of the trio of leading Ferraris, reportedly having 50-hp more than the new Lister. Moss took the next stint and was 3rd by around half distance, by then the weather had taken a turn for the worse, it rained heavily, but this assisted Moss. Unfortunately, due to an error at the previous pit stop, Moss ran out of fuel—the final churn had not been filled. Hansgen in the Cunningham “knobbly” tried to push Moss’ stricken car, but to no avail. Hitching a lift back to the pits, Moss got a can of fuel to fix the problem. However, 16 laps later he would be disqualified from the race due to receiving outside assistance. The car was retired, but Moss went on to co-drive Lake Underwood’s car, finishing 15th. Brian Lister was scathing at Cunningham not allowing him to control the Moss/Bueb pits, had he done so the fuelling error would not have been made.

Photo: Paul Skilleter

A few days after Sebring, Ivor Bueb was back behind the wheel of the Costin-Lister—this time a “works” car—for the Easter Monday meeting at Goodwood. In inclement conditions the new car earned its first success, winning the Sussex Trophy ahead of Jonathon Sieff’s “customer” Costin-Lister—so a double podium for the first race on English soil. This success was surely the works Listers retaining their UK dominance? No, results for the ’59 season and the new car turned out to be very varied. Bueb finished 4th in the British Empire Trophy and Bruce Halford took a soaking at Oulton Park ending his race in the lake. But surely the Costin car was quicker? Again, no! At the International Trophy race at Silverstone, Bueb in the Costin car couldn’t get within five seconds of Archie Scott Brown’s time just 12 months earlier. Another thing, car development was moving on apace and the big-banger cars were having rings run around them by the new light and nimble Lotus and Cooper cars. The next big test for the Costin-Lister was the holy grail of sports car racing, the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Photo: Willem Oosthoek Collection

Costin worked hard trying to get an advantage on rival cars, so new thinking and technology was needed. Braking was always a problem at Le Mans, and anything to give an advantage there was surely worth pursuing. He came up with an air brake, a wing affixed to two struts placed at the front of the car, whereby the driver could activate the device while at speed. Testing at Snetterton proved a failure. Firstly, due to the air pressure on the wing, the driver couldn’t move the lever to activate it and second, the bonnet was inaccessible with the wing fitted. With two fully race-prepared cars lined up at La Sarthe, one for Hansgen and Blond, the other for Bueb and Halford, this was an opportunity ready to grasp. Once more, it was not to be. The Hansgen/Blond car put a rod through the engine just over the four-hour mark—it was in 11th at that stage. The Bueb/Halford duo was faring much better, holding 5th place at two in the morning, until the three-liter Jaguar engine failed in similar circumstances to the sister car. Brian Lister was floored by the retirements—how could he have spent so much money and gained so much disappointment? Appearing to finish in a high position, even a podium, was surely on the cards? His faith and optimism in Frank Costin had reached a very low ebb, although it has to be said the Le Mans failures were fairly and squarely on the Jaguar engine, rather than the design/concept of the car. It would be a result Brian never got over, even relaying the story to the author on more than one occasion. The 1959 British GP sports car race at Aintree showed the Costin car to be an expensive “white elephant” when Jim Clark, at the wheel of HCH 736, a less sophisticated “flat iron” car (BHL 5), entered by Border Rievers, finished 4th ahead of both Bueb and Halford, in 5th and 6th places, respectively. As a result, a “hold” was put on the new space-frame Lister and Costin departed by the end of the summer of ’59. Brian’s withdrawal was further compounded by Peter Blond’s lucky escape after crashing his Costin-Lister at Brands Hatch (Brian withdrew the team from that meeting), travelling back from Brands Hatch to Cambridge he heard that Jean Behra (linked with a drive for Lister in 1960) had been killed at Avus and, on his arrival home, his wife Jose greeted him with the news that Ivor Bueb had died following a lengthy spell in hospital after crashing his BRP Cooper-Borgward during a French F2 meeting at Clermont-Ferrand on July 26. The dream was over, those halcyon days were all but a distant memory and the team took its final bow at the Tourist Trophy meeting at Goodwood on September 5, 1959.

BHL 133

It was the great success of the 1958 Lister Jaguar car that Briggs Cunningham owned that led to a vigorous order book for the 1959 car. Cunningham’s success had included consecutive American SCCA titles for Stirling Moss, Masten Gregory and Walt Hansgen using the cars from Cambridge in his famous livery of white with blue stripes. In all, 14 Costin-Lister cars were built (15 if you add the unfinished space-frame car later sold to Jim Diggory). Many of those sold to the USA market were shipped as a rolling chassis ready to take a Chevrolet V8 engine. Chassis BHL 133 was one of the last built. It was exported to Carroll Shelby Sports Car International, an importing company jointly owned by Jim Hall and Carroll Shelby—the only Costin-bodied car Shelby imported, although he’d previously taken delivery of no less than six “Knobbly” cars. The red car was sold to Pete Harrison, who installed the small block Chevy V8 engine himself. He competed in a number of East Coast American races, entered under his father’s business name, the Harrison Radiator Company. He had some good successes with the car and campaigned it throughout the 1960 season, until ’62. The second owner, from 1963-’65, has been established as Ross McCain, who continued racing. During 1965, the car was sold to Phil Johnson of Milwaukee, who partly converted it for pure, high performance road use.

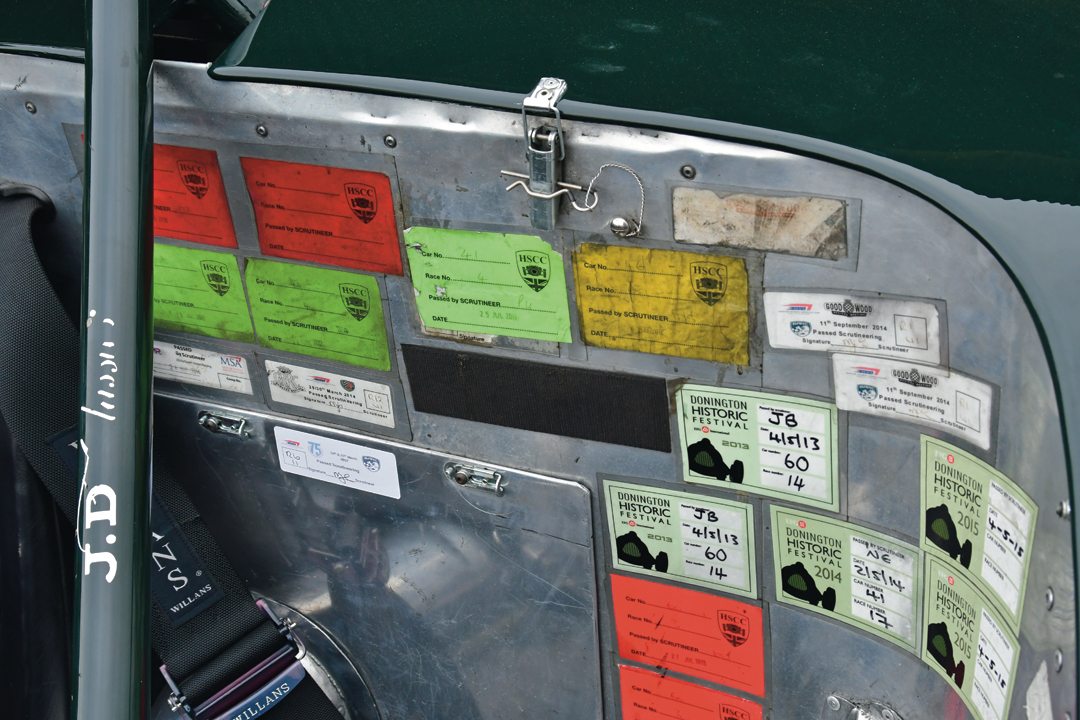

Photo: Ferret Fotographics

The car was sold once more in the U.S. in 1972, by the recently deceased Joel Finn of Connecticut, to British car broker Charles Renwick, who in turn immediately resold it “sight unseen” to John Pearson in Northamptonshire, UK. It has to be said that the car, by that time, was pretty derelict and when viewed at the dockside Customs Office, in Southampton, bearing the stickers “DEAD CAR,” Pearson thought the best course of action was to simply push it over the side into the water! After a discussion, the “heap” was determined not to warrant any import duty (!) and was taken to Pearson’s garage awaiting restoration. Classic car dealer Anthony Crossingham eventually purchased the car, now restored with a Jaguar XK engine, the Chevy engine mounts replaced with Jaguar mounts, and an E-Type gearbox installed. John Harper took delivery of the car, replacing the metal bodywork with fiberglass—this was circa 1974. By then painted yellow (in deference to entrant Caterham Cars), the car was back in competition with driver Peter van Rossem at the wheel. The yellow livery attracted many nicknames, including “The Yellow Peril” and “The Lemon Drop.” By 1976, the car moved on again to founder of the Mulberry fashion house, Roger Saul, who shortened the nose. Journalist and qualified engineer, Michael Bowler saw the car entering a particularly successful racing period when he won the FIA Historic Sports Car series in consecutive years, 1979, 1980 and 1981, also winning the 1981 Lloyds & Scottish Championship. By this time, the car had reverted to a long nose configuration and the yellow livery had been replaced by a more sedate light Cambridge blue body with dark blue stripes. The next owner, Michael Freeman, campaigned the car at numerous events before it was housed in the Stavelot Motor Museum, Belgium, near to the Spa-Francorchamps racing circuit—another color change, this time to burgundy with cream striping. In 1997, another owner, another color, this time green. New owner David Newman was ably assisted by Win Percy to set up the car once again for some successful racing, prior to it entering the hands of Chris Keith Lucas’ CKL Engineering. After much restoration and a 6th-place finish at the 2006 Goodwood Revival meeting’s Sussex Trophy, the car now is in the hands of current owners JD Classics of Malden, UK. Last year, 2016, the car won the Stirling Moss Trophy at the Donington Historic Festival, also winning the Le Mans Classic and the Sussex Trophy at the Goodwood Revival.

Driving BHL 133

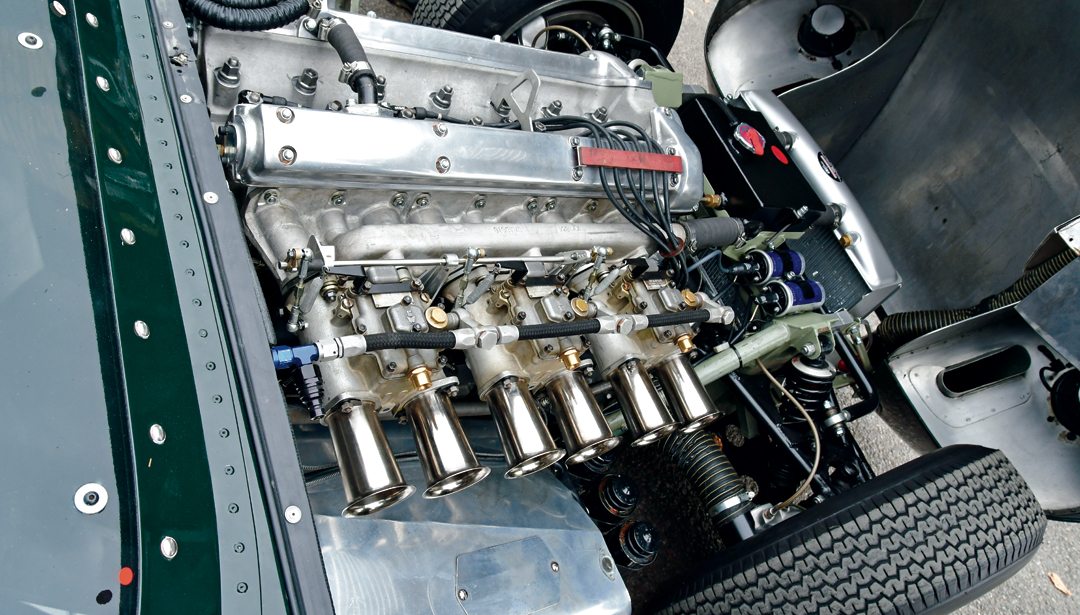

Ironically, our test is set at Le Mans—the place the Costin-Lister should have excelled, had it not have been for the defective three-liter Jaguar engines. Today, the car is fitted with a 3.8-liter engine, rather than the smaller three-liter unit of the period. The weather is clear and fine, the track surface is dry and there’s that warm feeling of being in the cradle of world sports car racing. BHL 133 has already been warmed and is set to take on the legendary 8.48-mile circuit. After crossing the start/finish line at speed, approaching the first corner, it’s rather challenging as it’s tightening, as well as having to start slowing the car down ready for the chicane prior to the Dunlop bridge. It’s probably the trickiest part of the circuit for this particular car, because it needs a certain amount of patience as the car can bite here if driven without confidence. Having gathered it all together, you can take the first left-hander of the chicane quite smoothly. It has been noted that the car lacks traction, so care is taken to exit the right-hand bend of the chicane to get enough grip to climb up the hill toward the Dunlop bridge. Care has to be taken not to spin the wheels with hard acceleration as this will heat the tire and thus increase the tire pressure. Too much tire pressure causes the tire to crown and lessens the tire footprint, so flamboyance here is a definite no. Unlike Stirling Moss on the first testing of the car at Silverstone, our tires are set the same pressure all around. Under the Dunlop bridge, we’re now dropping down the hill, we’re smooth through the left-right chicane as we approach Tertre Rouge, the right-hand corner that brings us onto the Mulsanne. It’s a question of being in a position to see the exit of the corner nice and early, we don’t want to overdrive through here—a tenth of a second lost here will lose us a second by the time we get to the first chicane on the Mulsanne itself. So, we’re using the road and the clipping point of the corner to exact a great exit, pinching a bit of curb at this point is not a bad thing as they are quite smooth. At top speed, toward the first chicane it is possible to hit the 175-180 mph—6,500 rpm in fourth gear (just imagine driving in 1959 without the chicanes). Having said that, holding the car flat out for long periods of time severely affects carburetion, there is a danger the car could run lean. So, the art of driving fast in this car, in fact most cars of this period, is to modulate the throttle. Braking now, around the 200-meter board, helps to negotiate the “bus stop”-style first chicane. At night, in the dark, it is quite difficult, especially with the lights on a period car such as this, to sense your arrival speed at this first chicane. Taking the chicane breaks the flow of the car and can affect the rhythm of your driving—it takes some getting used to. It’s a question of going in, balancing the car on the throttle and getting a good exit and acceleration for the second part of the straight. At this point, it’s better to lose some speed on the way in rather than just barrel into it. The second chicane is a little friendlier, but still slower in is the better approach. Building speed on exit we’re soon back up to fourth and at top speed. The first part of the kink prior to the Mulsanne Corner is a crest, the second is able to be straight-lined. Here, we’re now braking to take the right-hander, again looking for the apex, which at this point is below you. Multi-tasking here is a necessity, braking, changing gear, turning, looking for the apex and ensuring a good exit is essential. Running down the Indianapolis Straight in top, we’re approaching the most enjoyable corner on the circuit, the car really takes a set into there as the camber seems to help you through, depending on your speed and approach the corner can be taken from fourth to third gear, or even fourth direct to second gear, as we prepare to turn left and then right at Arnage. We’re now building speed again, a nice left kink and then preparing for the approach to the Porsche Curves. It’s very possible to make a good amount of time through this part of the circuit. The left-hand entry to the Porsche Curve is a little daunting with the walled sides—it can lead to tunnel vision at this point. Being smooth and precise through the next double right-hander can boost your lap time here, but care has to be taken not to overdrive the car. Exiting the corner, we climb up the hill to an off-camber left-hand curve, which is blind on turn-in. Again, it’s possible to pinch a bit of curve here and make some more time prior to the short straight that leads to the chicane prior to the start/finish straight. Throughout the lap, the car has had a tendency to oversteer, and thinking ahead and anticipating the car’s reaction to the circuit is paramount. It has to be said this is not the most forgiving of cars, and keeps the driver in an acute concentration mode throughout the lap. It could be described as a “pit bull” raring to go, relieving the driver of control if not careful. The car excels on the faster parts of the circuit, but the traction issues cause it to lose time on acceleration through the slower sections.

Conclusion

Clearly, Brian Lister had all the ingredients of a great car designer, albeit he was not necessarily qualified as such, simply gaining hands-on experience from his enthusiastic racing. It is a measure of the man, his team of mechanics (many worked both for Brian and the original George Lister Company) and, of course, a certain Archie Scott Brown, that from this basic enthusiasm and minimum expense they took on all and sundry to become a truly class act. The loss of Scott Brown wrenched at Lister’s heart, a lesser man would have simply packed up and walked away. Not Brian Lister, who showed a great depth of character. He didn’t continue in the sport by merely paying lip service to fulfil contracts and give his men employment. He genuinely had that ambition to win and achieve—despite losing such a great driver and dear friend. His belief, founded on what he had seen and others confirmed, was that Frank Costin held the key to a new era of racing car design. To his chagrin, that expensive journey offered much, but proved fruitless. In later life, he admitted, “I really regret ever doing the Costin body. If I had my time over again I would clean up the ‘knobbly,’ and build lower and smaller, like the 1957 car and the Lister-Maserati.”

All too late, Lister found he, like others, thought there was a future in the big-banger-engined cars, but time and the evolution of motor racing showed the more nimble, lightweight cars were to be the future. The subsequent deaths of Ivor Bueb and Jean Behra were simply too much to allow him to continue. The legacy of Brian Lister and his small Cambridge outfit can be seen on racetracks today, with regular entries, podium places and victories for his eponymous cars, something even the Costin-Lister shares.

SPECIFICATIONS

Engine: Period – Chevrolet V8 / 6-cylinder Jaguar 2986-cc, Current – 3.8-litre straight 6-cylinder Jaguar XK

Gearbox: 4-speed manual

Brakes: Discs brakes all around

Steering: Rack and pinion

Body: Aluminum panels

Frame: Steel tubular

Suspension: Front – double wishbones, coil springs over telescopic shock absorbers, Rear – DeDion axle, twin trailing arms, coil springs over telescopic shock absorbers

Weight: 1687 pounds

Length: 172.8 inches

Width: 67 inches

Height: 31.1 inches

Wheelbase: 90.7 inches

Track: Front – 52 inches, Rear – 53.5 inches

Resources

Bibliography

Powered by Jaguar by Doug Nye

Archie and the Listers by Robert Edwards

Lister Jaguar: Brian Lister and the cars from Cambridge by Paul Skilleter

Stirling Moss: My cars, my career by Doug Nye

Le Mans 1949-1959 by Quentin Spurring

Periodicals

Autosport, Motor Sport, The Automobile and Motor Racing

Thanks

Sincere thanks to all at JD Classics for assisting with this profile and making the car available on more than one occasion. Thanks too to Edwin “Dick” Barton, Chris Ward and Gary Pearson for their kind assistance and factual input.