Photo: Andy Thorpe

Was Alvin “Spike” Rhiando really Archibald Stansfeld Belaney?

Well, the answer is no, but if you haven’t got anything else to do for the next twelve hours you could find some good entertainment by Googling both those names and taking a trip into fantasy land…it’s worth the trouble.

Belaney turned out to be the real name of a man who came to the UK in the 1930s as Grey Owl, a member of the Canadian Ojibwe tribe, and gave many lectures as a native expert on tribal cultures and wildlife. After his death, it was discovered that he had been born in Hastings in Sussex and had created an elaborate, though interesting, identity for himself!

“Spike” Rhiando, or possibly Alvin James Franchetti or Spike Antonio Riando—take your choice—was well known on the British speedway motorcycle circuit in the 1930s. While telling people variously that he had been born in South Africa or the USA or Canada, the reality was that he was, in fact, born in Berlin on April 6, 1910, to Albert John Stevens and Elizabeth Albrecht, and was named Albert James Stevens. His father was the circus juggler Rebla, originally from London, and his mother was also a theatrical artiste, born in Leipzig. When Albert was 17, his parents divorced, having returned to London. The father went off to Australia and the mother remained in London until her death in the 1950s, but young Albert “disappeared” in 1928, and there is no information about him until the mysterious speedway rider appears.

Photo: Mike Jiggle

It would seem that Stevens reinvented himself as Spike Rhiando possibly while doing some midget car racing in the USA and Canada in the early 1930s. It is interesting that he may even have been very close to the stomping ground of one Grey Owl in Canada in 1933 and returned to the UK around the same time as the alleged “Indian brave.” I can assure you, though, that they were not one in the same! Rhiando is remembered for his somewhat futile efforts to get midget car racing going on the British cinder tracks, which were hosting two-wheel racers at the time. He was often described in publicity material as the “American dirt track racing ace,” though he was neither American nor, in fact, an “ace.” He did, however, have a wide following and a number of friends prepared to listen to his sometimes outlandish tales. He apparently worked for the Caterpillar tractor company, in their British division, during the war, and signed on for Clement Atlee’s odd Tanganyika Ground Nut project post-war, from which he earned a considerable amount of money.

enter 500-cc racing

Rhiando’s funds allowed him to enter the rapidly growing post-war sport of British F3 or 500-cc racing, and he was one of the very first customers for a production Cooper racing car, the Mk2. John Cooper himself said it was Rhiando’s idea to insert a V-twin engine into a Cooper Mk2, and Coopers modified a car to take the 1000-cc version in which Rhiando appeared at the Manx Cup in May, 1948. This car was painted in a rather garish gold lacquer, leading to it being dubbed the “Flying Banana.” However, it turned out to be pretty effective and in 500-cc format, Rhiando won the first large scale race for the new class at Silverstone in October.

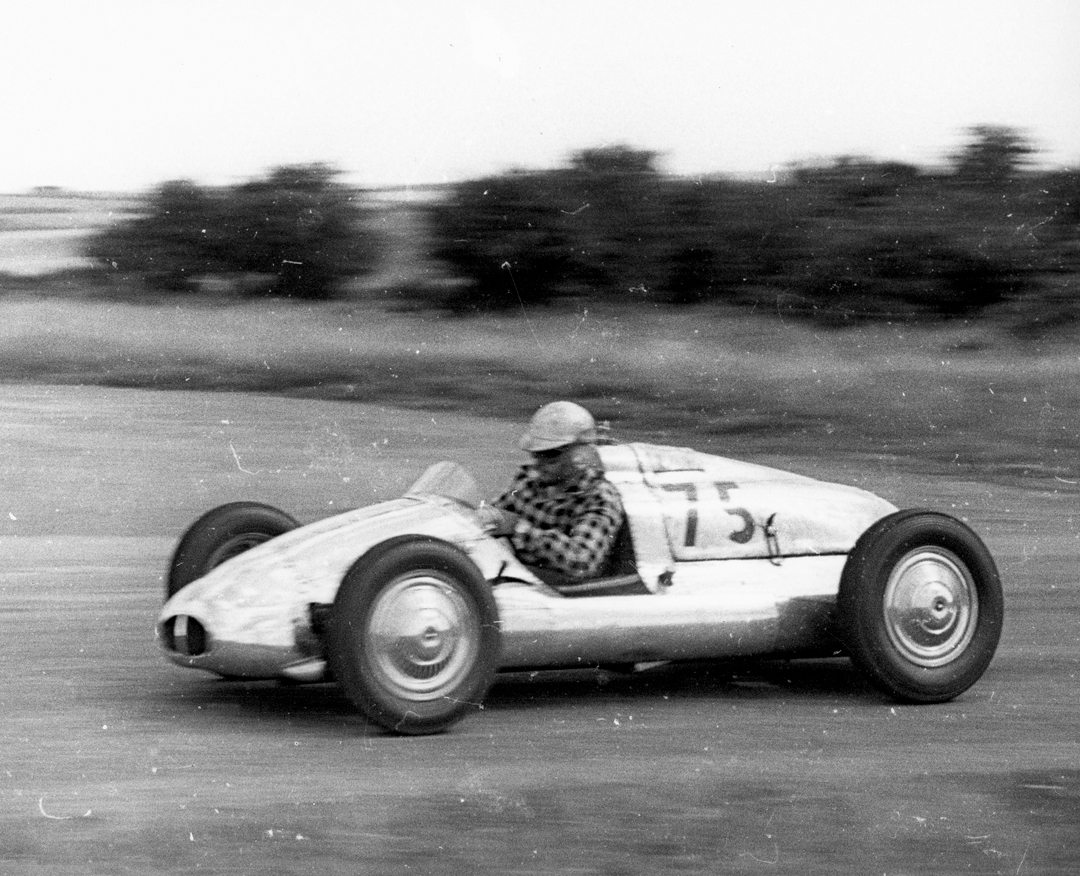

Photo: Damon Hicks

That was a shambolic race with the flag being dropped before some drivers were in their cars. Spike led John Cooper himself to the flag after one Stirling Moss dropped out, with Eric Brandon finishing 4th. It was a field of nearly 35 cars, almost every 500-cc car in existence at the time. He then took part in many more races with the Cooper in both 500- and 1100-cc format, getting 6th at Goodwood in April, 1949, and putting it on the front row at the Grand Prix meeting in May. Moss won this big event from Curly Dryden, while Rhiando retired.

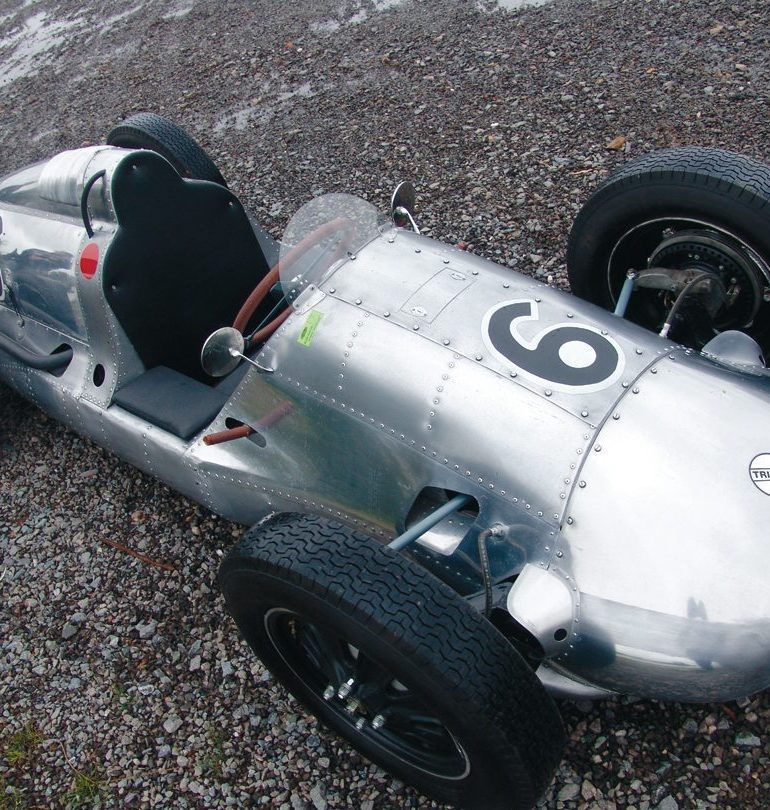

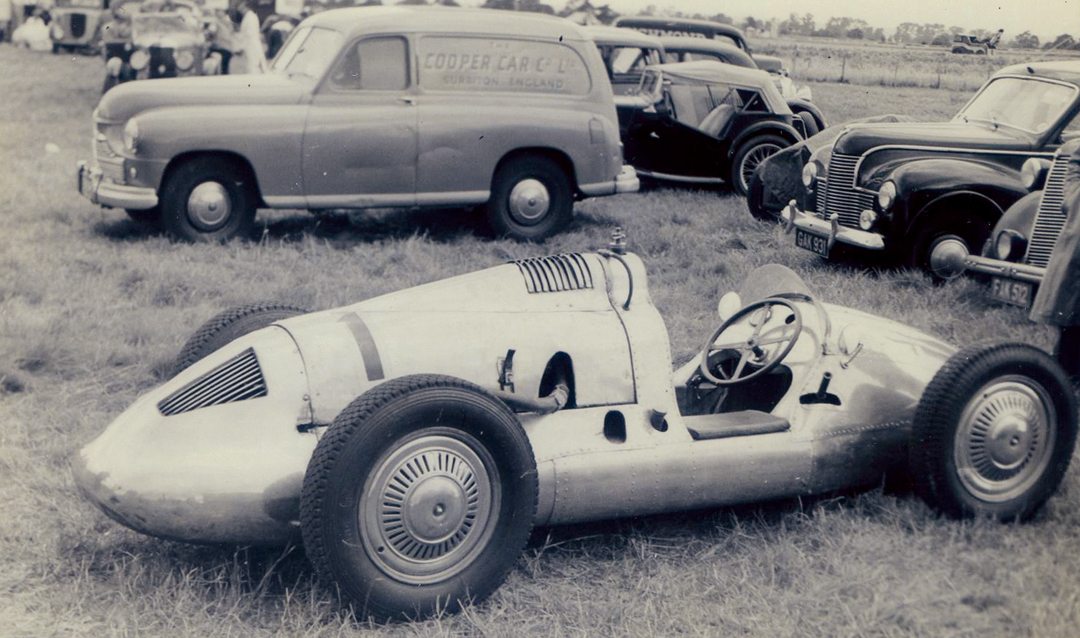

Enter the Trimax, or Rhiando Trimax, or Rhiando Rocket! The 1949 season became a battle of the Coopers, or more accurately a battle between the Coopers and whatever anyone else could produce to challenge them. The International Trophy was due to take place on August 20, and the pre-entry included Rhiando to be driving a Rhiando Trimax. It was known that Rhiando, like others, was trying to find something to beat the Coopers. What he came up with was a machine that was unique, and in historical terms, much overlooked, for the new car was a vehicle type few people had seen—a monocoque.

The “tri” in Trimax announced Rhiando’s early intention to build a car capable of taking engines of 500-, 750- and 1000-cc capacity. This was a clever idea, but proved to be, in part at least, responsible for the car’s difficulties. Early reports, before 1949 was over, described the main features as including independent suspension all round by means of swing arms, torsional rubber suspension units adjustable for setting the suspension arms, aircraft-type chain and cable steering, light alloy ventilated wheels, rubber fuel tanks and a fully stressed body-cum-chassis. Rhiando claimed that the body was designed using wind tunnel tests, and that the rest of the car would suit the final body shape. There has been considerable speculation about the use of a wind tunnel and even more skepticism!

Photo: M. Aikey

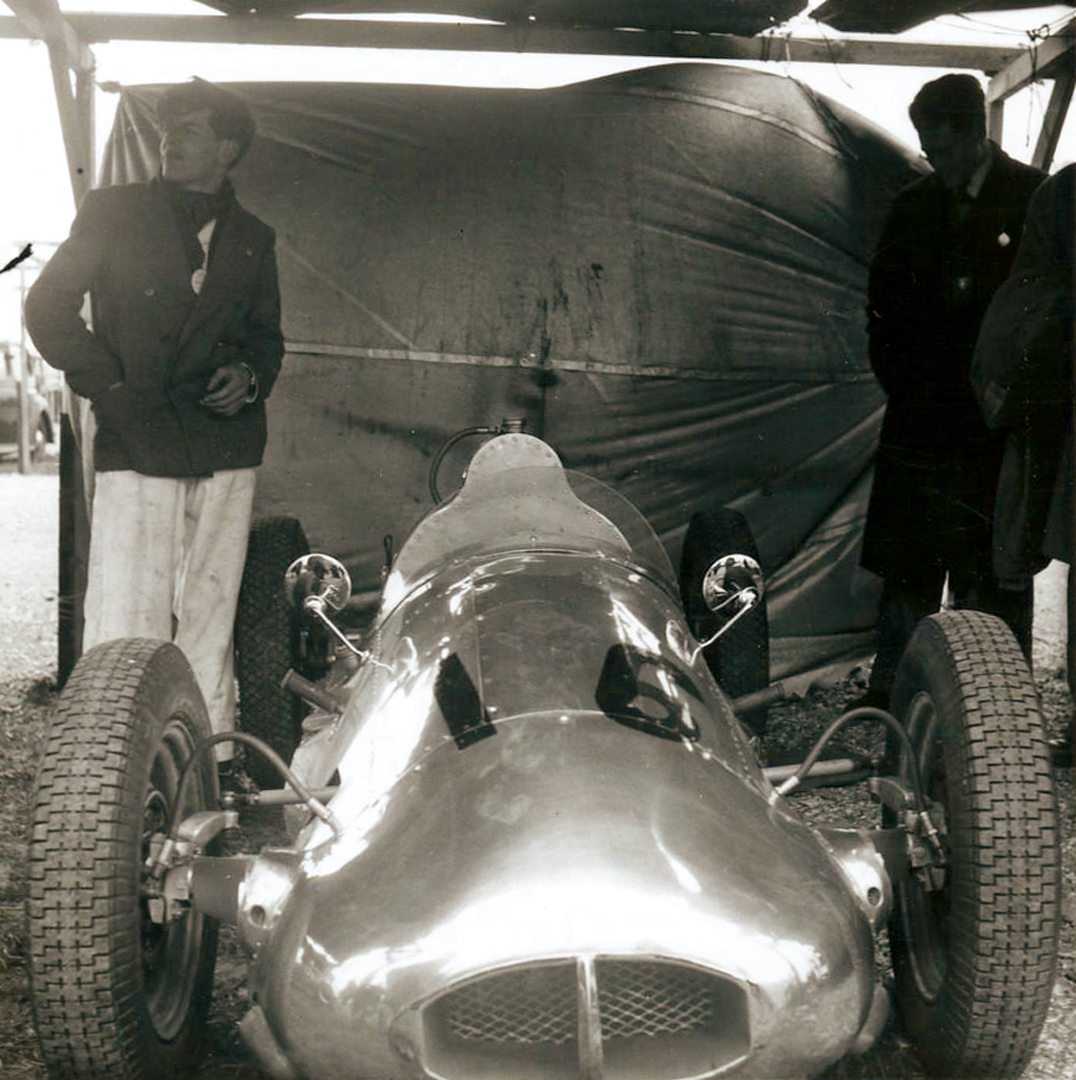

Though the wheelbase and track are only 7 feet-1 inch and 3 feet-10 inches, the body makes the whole machine look larger, being about 12 feet in length. It is a fairly conventional design, though the body shape is attractive and somewhat mini-Auto Union in appearance. Apparently, one of the objectives was that the car would be developed into a proper F2 car with supercharged engine and the all-in weight would have been some 900 pounds. However, a 500-cc F3 car of the period weighed in at about half that, so the Trimax was always going to be heavy. Rhiando is known to have claimed that he eventually built three cars—one the 500, the second an 1100 and a third sold to Africa. Again, there is a lot of skepticism about this, as well as comments like: “there are no photos of two cars together!”

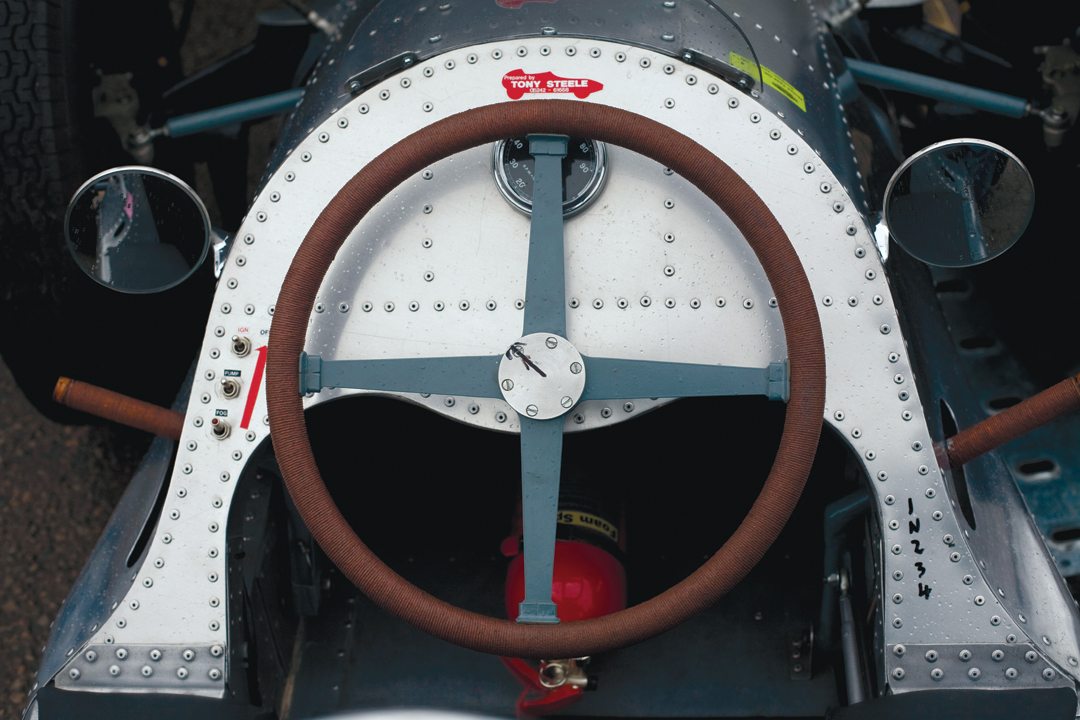

Nevertheless, a great deal of thought went into the design and construction, and what Rhiando was creating was clearly a pioneer effort. The body was built up in “duraluminium” in both 16- and 18-gauge sheet, and beautifully pop-riveted. The main strength of the monocoque derived from the two sponsons running the length of the wheelbase, nine inches square at the largest point. Entry holes were cut and the rubber fuel tanks were fitted into the sponsons, each tank holding just over five gallons, and connected by flexible pipe lines. The two side sponsons are integrated into the structure by means of two cross tubes and a pair of bulkheads, one in front of the driver and one behind. A single floor forms the bottom and is stiffened by longitudinal stringers riveted in place. The front bulkhead carries the steering wheel, but is pierced to allow the driver’s legs through to the pedals. This is very narrow and required some work to adjust to, but it does lend much more strength to the chassis.

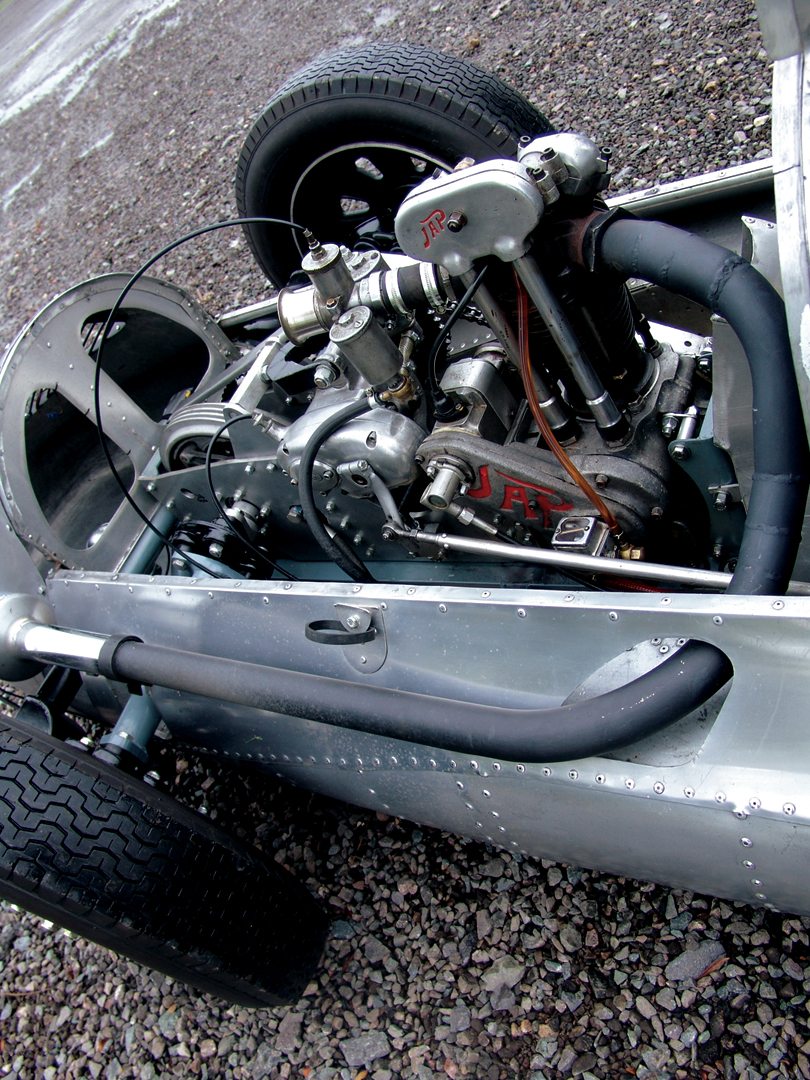

The suspension design was equally interesting, with the wheels mounted on swing arms that pivot on the ends of the top tubes with a Metallastik rubber-bonded suspension unit alongside each of the swing arms. The bottom tube ends were blanked off and are used as mountings for the double-acting piston-type hydraulic shock absorbers. The suspension bore a resemblance to the period Alta F2 car. The original wheels were designed as bolt-on type, and carried the latest Dunlop tires, 5.25 at the front and 6.00 at the rear in period. Sixteen-inch diameter wheels also added to the illusion of a rather larger than ordinary 500-cc machine. The original 500-cc engine was a Speedway J.A.P. mated to a Norton gearbox.

Trimax goes racing

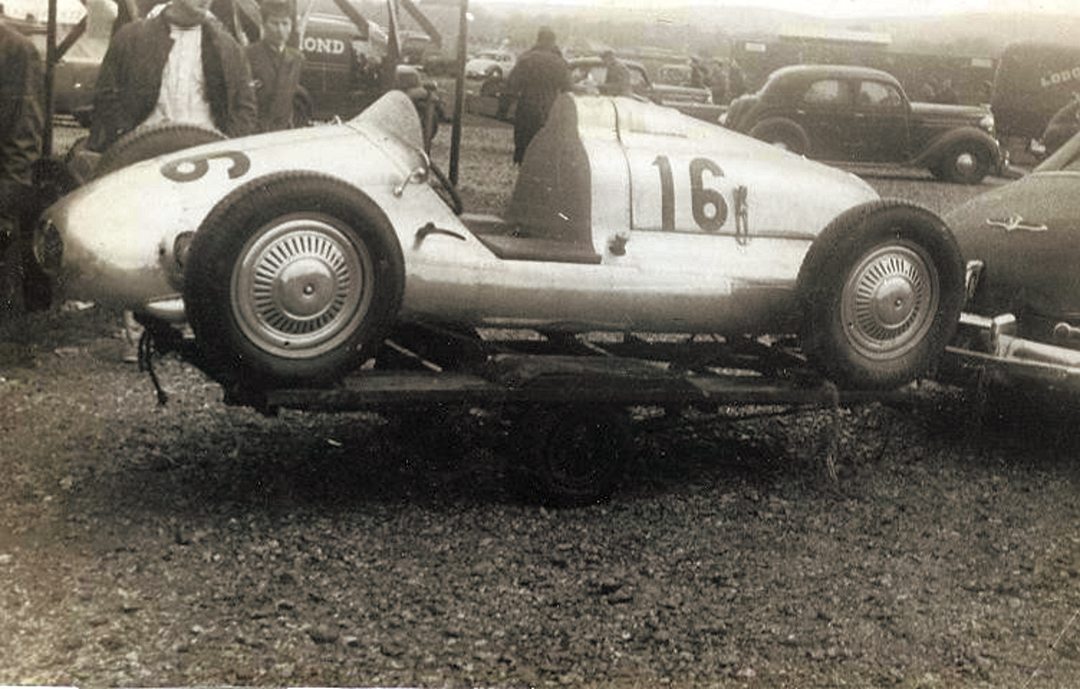

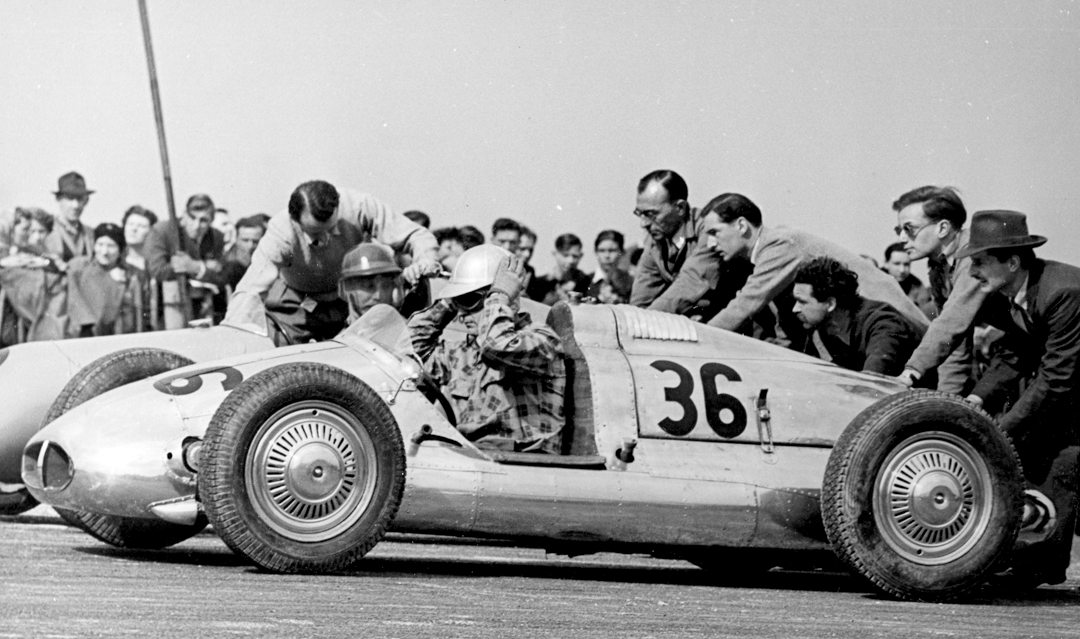

Though Rhiando had made entries for meetings at Shelsley Walsh and Silverstone for the Trimax in 1949, he either did not appear or brought his Cooper instead. The Trimax then made its racing debut at Goodwood at the Easter meeting on April 10, 1950. This was only the second meeting of the year, but it brought out many of those who had supported the new formula in the first two years and would go on doing so. The field included John Cooper in a Mk IV, Austen May in a Mk2, Peter Collins in his Mk III, Alf Bottoms in a Cowlan JBS and Paul Emery in an Emerson. Rhiando was on the fifth row, but he never completed a race lap as the gearbox gave up. Collins and Cooper crashed, and Curly Dryden won in his Cooper Mk2.

In mid-April, all the main runners were at Brands Hatch for several 500-cc races, where John Cooper and Ken Carter were among the winners, and where the Trimax again faltered, losing the engine in one heat and retiring after eight laps in another. The car was entered for the British Grand Prix meeting at Silverstone but did not appear, and did the same at Monaco, where Stirling Moss won a great race from Harry Schell, both in Cooper Mk IVs. In late May, the 500s were at Goodwood for the 500 International Trophy. The now occasionally fragile Trimax was 13th on the grid, but again only managed a few laps. The final produced a torrid battle between Collins, Dryden, Cooper, Dickie Stoop and Ken Wharton that was won by Dryden, half a second ahead of Peter Collins.

The regular 500 runners were now venturing abroad for a number of races, and the category was gaining support across Europe, where drivers such as Jean Behra, Raymond Sommer, Elie Bayol, Rene Bonnet and Curt Lincoln would enter combat with the top Brits. Rhiando next appeared at the Manx Cup meeting with a Triumph engine in the Trimax, but yet again he was in trouble. A similar fate awaited him at Brands Hatch and at the Rest and Be Thankful hillclimb. Back at Brands on July 23, the car managed its best result with a very good 3rd place in one heat and 4th in another among very tough opposition. He was out of the results in the important final, and was by now getting discouraged with the car’s unreliability.

Photo: Rabagliati Collection

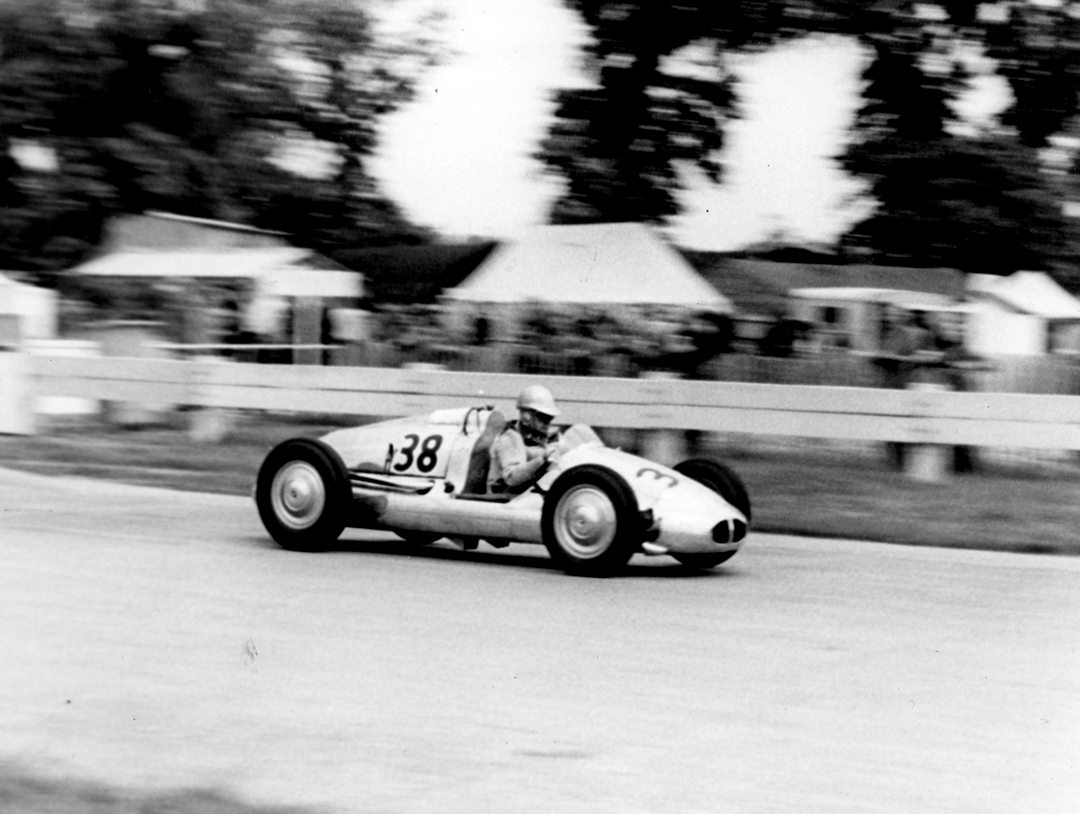

A hillclimb followed at Blandford where the car ran well. Rhiando looked better at Silverstone for the Daily Express Trophy meeting, qualifying 15th. He finished 14th in one of the hardest races of the year, won by Moss from Raymond Sommer with Peter Collins in 7th. The first ten cars were covered by a few seconds at the end. As the season came to an end, a 1097-cc engine was installed for two races on the program at Goodwood. The engine was reliable and Rhiando finished 5th in both races, which featured up to 2-liter cars.

The story gets a bit murky at this point—nothing sinister, just a little unclear. A number of contemporary and historical accounts say that Rhiando had tired of the Trimax’s unreliability and sold the car to an American at the end of 1950. He is reported to have purchased Dennis Flather’s “Flather Special” in an attempt to be more successful in 1951. Indeed he did purchase this car, and indeed he had a reasonable amount of success with it. Nevertheless, there is a well-known Guy Griffiths photo taken at Goodwood on March 29, 1951, showing Prince Bira standing next to Stirling Moss who is in the cockpit of an HWM-Alta F2 car. Looking over Bira’s right shoulder you suddenly have a Leonard Zelig experience, for there in the background is Spike Rhiando sitting in the Trimax, which is listed in the program as the Rhiando Rocket. This race, the Lavant Cup, was for the mostly forgotten voiturette class of cars from 1100- to 2000-cc. Ahead of Rhiando on the grid were Moss, Kenneth McAlpine in a Connaught and Eric Brandon in a Cooper, while behind him were Peter Collins’ Cooper, John Heath and others.

Photo: Rabagliati Collection

Now, was the Rhiando Rocket simply the Trimax with 1100-cc power, or was it one of the mysterious other cars? Answers on a postcard (or email!). Whatever the case, the old Rhiando “luck” was in and he lasted one lap, with Moss going on to win. Peter Collins didn’t manage a single lap. While Spike is recorded doing a number of 500 races in 1951, he also appeared at the International Avusrennen in July—an F2 race—where he drove a works Cooper. This race featured a number of well-known German drivers, who dominated, and Rhiando dropped out after five laps.

Whence Spike Rhiando?

Rhiando was tiring of racing and looking for pastures new—and bizarre. He “discovered” the uses of fiberglass and designed and built a neat, fully bodied Villiers-powered scooter. To prove its durability, he set off alone to ride/drive from London to Capetown! Somewhere in the Sahara he was found by a French Foreign Legion patrol in a bad state in the shade of a large rock. The scooter had run well and is still alleged to sit next to that rock. Rhiando then worked with American Bill Curtis to build a large fiberglass car in Ireland to be sold to the USA and the UK. Although 10,000 cars a year were planned, only eight were built and the project—the Shamrock—failed. The spares were ultimately thrown into a local lake! Some four Shamrocks are still thought to exist. It is thought Rhiando stayed in Ireland and died a few years later—or maybe he died in London in 1975. Apparently, there exists a grandchild now working to put the whole story together. Good luck!

the Trimax goes west…then east!

The details of when the Trimax went to America and to whom are blurry. There is a photo of the car at the Madera airfield in California dated November 1952. A lengthy troll through the 500 Register’s database of 500-cc races turned up very little in the way of results, although there was the Trimax at the Palm Springs road race on January 23-24, 1954, carrying race number 40, driven by one MacDonald Whitman. Some records show it entered by Harry Morrow at Torrey Pines on July 10, 1955, for Art Varney, and again at Santa Barbara on September 3 and Torrey Pines again on October 23, with the same entrant/driver combination. Morrow was a fairly well-known Cooper 500 driver himself in that period.

A Paul Gager raced the Trimax in 1956: June 24 at Pomona; July 21 at San Diego; October 21 again at Pomona and November 18 at Paramount Ranch. It seems to have failed to finish at all of these races, and the trail of races ends there—for the moment only, I hope. When this issue of VR lands in California, I am hoping the bells will start ringing and I will be inundated with new information and photos! There are stories of the car having a variety of engines in this period, including a Harley-Davidson. It sat in the collection of Jack Mayes in Chicago for many years before being brought back to the UK by Duncan Rabagliati, and in 2007, was meticulously restored by Tony Steel and Keith Roach. Duncan is the historian of the 500 Owners Club and heads the Formula Junior Association.

Photo: Rabagliati Collection

Driving Spike’s Rocket

As far as I know, the Trimax never raced at Mallory Park in Leicestershire, as it would have been in the USA when the challenging little circuit was opened in the mid-1950s. It had done very little mileage in the period between its restoration and our test at Mallory, though its presence “back home” had certainly been noted. It still had a degree of fragility, and Tony Steel, who did the work on it and brought it to Mallory, was anxious that I treat it with respect. That was quite likely as it was a typical damp English day. Since a lot of other cars were out testing, there was not going to be time to do leisurely car-to-car photography. Everything would have to be done out in the midst of Formula Fords, Formula 3s and Formula Renaults. All the other cars were at least 40 years younger!

As the rather gorgeous “sort of” Auto Union lookalike rolled out of the transporter, it quickly drew a crowd and a lot of attention. The guys who go midweek testing are a pretty jaded lot, and have seen it all, but that didn’t stop them coming over for a closer look. Everybody knew it was a 500-cc car, but several people asked “which one is this? We haven’t seen this before.” Which is indeed the case if you weren’t following the 500 scene in the UK some 62 years ago! One fairly smug Formula Renault tester said he would be sure not to run me over. We’ll see about that.

Though the initial impressions of the car back in the Fifties were that it was quite large, it shrinks a bit when you focus on getting into it. Tony Steel said, “I don’t think you’re going to manage that.” The clever strengthening panel that is really just a cut-out to hold the dash and steering wheel is very narrow and it took several attempts to get both legs through the gap and down to the pedals. While the clutch and gearchange operation was all very effective, it did present some issues. The box is sequential, with first all the way forward, then a gap for neutral, and then back for second, third and fourth. The clutch was a touch sensitive, and because of the shortness of the cockpit, I found myself with legs bent and my left foot having no place to go except to remain about a quarter inch above the clutch pedal. Nevertheless, that arrangement worked—what the 100-mile race at Silverstone would have been like to drive I don’t know. The box was immensely flexible and I tried out all the permutations on a wet, drying, puddle-ridden dampish circuit through the day. Loved that Norton box…totally predictable.

Once ensconced down in that cockpit, it feels surprisingly comfortable. It is open on the sides and looks exposed, but I never felt exposed. The seat and narrow frame hold your backside in place. The elbows may be out in the fresh air, but there was no feeling that I might fall out, especially as you sit quite close to the steering wheel. The worry was that if you did fall out, it would be only halfway as your legs would stay put! Those 500 drivers were brave. The dash is basic, sparse even: a rev counter reading up to 7000 rpm, though 6000 was the mandatory maximum and in the conditions I remained happily closer to 5000 than 6000. There are switches for ignition, fuel pump and fog light on the left and not much else. The handbrake and gear levers are wonderful. They are two leather-covered handles that protrude through the bodywork on either side and are simply moved forward and back. One spectator asked if they were “handles to lift it up?” There is a modern extinguisher under your legs, and no belts.

From the outside, it’s a beauty. Porsche ’60s GP rear end shape, side view of the Auto Union, stubby but shapely front, all those curved vents and fine little touches. It was an extraordinarily well thought-out and engineered machine. The car was sitting on racing Dunlops, 5.50-16 front and rear. The grip from these was superb, especially in the wet, as we will see. The car runs on methanol, which is pretty high maintenance, needing to be drained completely after use, then flushed with ordinary fuel to avoid corrosion.

Having not run in a number of years, except for just a few short laps at Snetterton recently, our test car was going to be interesting as I would see whether the old unreliability was still there. As it turns out, I believe we set a “distance record,” making it go further than it had in 56 years! The 500-cc J.A.P. engine barked into life for a bit of warmup and then a few laps for learning. It was “semi-wet” conditions, which the Dunlop tires really seemed to like. It was quickly possible to stay on 5000 rpm up and down the box. I had been told that the brakes weren’t that great—there is a single brake at the rear, a la BRM—but they worked fine, only really needing some harder use at the second-gear hairpin. The chain-and-cable steering system, in aviation style, works well and is fascinating to look at, accessed by a panel in front of the efficient little aeroscreen.

I was going down to third for the long, long right-hander at the end of the Mallory straight, and tried it in fourth a few times as well. In third, you can get the revs up as you whistle down the back straight, now in fourth. Then it’s down to third again for the Esses, holding third all the way up the hill to the hairpin, down to second, third as you reach the challenging diving left-hander at the Elbow, and snatching fourth just before the pit wall. In the second and quicker session, still damp, I came upon that Formula Renault driver and dived up the outside at the Esses and whipped past! That was good! The Trimax ran smoothly throughout, went the required distance, and we only stopped when the inherent 500 vibration shook the oil pump loose and we thought it would be best to stop.

So there was history. It was fantastic to drive this car back in its homeland. Since the test, the Trimax went back to the Goodwood Revival and again beat the old jinx, finishing well. The car is now up for sale, though I have a feeling that Duncan Rabagliati really likes his machine and may want to continue playing with it. It could now mount a new challenge to the Coopers in 500 racing—there are lots out there in historic races.

And please, if you know more about either this car or Spike, let me know.