The more in-depth summaries of the life and career of Phil Hill have focussed on three significant aspects: the racing accomplishments, the complex nature of the man, and the fact that he was an underrated driver. Phil died of respiratory complications due to Parkinson’s disease on August 28, 2008. He had intended, in true Hill tradition, to be at Monterey but had ended up in the hospital instead. His strong link to motor racing had been emphasized not only by his attendance at so many historic events worldwide, but also by his active participation until very recently. Those of us who saw him at the Monaco Historics in 2004, driving the Alfa Romeo 6C 3000CM which he put 2nd on the grid, were totally astounded by the performance. He was in his late seventies when that happened, and he had recently won in that car at the Le Mans Classic. Many commented on just how hard he had been driving. When I mentioned this to his wife Alma, she shrugged her shoulders and smiled: “You know what he’s like.”

When Parkinson’s started to make inroads, Phil occasionally cut his schedule back…a bit. It was a shock to many to see Phil looking frail and, at times, having to work hard to have a conversation. At Monaco in 2006, having spent some time with him in the historic paddock on Friday, he called me over the next day and said, “Thanks for talking to me…I think I’m scaring people!” Then at the Goodwood Revival, having got his medication sorted a bit better, he was in fine form, giving interviews and driving cars in the tribute to himself. All the sparkle was there, and that endeared him even more to his many, many admirers.

It is one of the great privileges as a motoring writer to have been able to work with and to know Phil. When I started on the Ferrari 156-Sharknose book in 2000, I made early contact with Phil, knowing that the book would have less relevance without his involvement. It wasn’t an easy start.

“How will I know that you won’t portray me in a negative light?” he asked, during the first conversation. I was stunned. I explained that, having followed his career with unswerving admiration since about 1954, it wasn’t that likely. I thus agreed to make sure he saw everything I wrote about him before it went for publication, and out of that grew a close working relationship which I have valued ever since. Even after some years, I could hardly believe it when the phone rang and my wife Nancy would say, “It’s Phil.” I could not get my head around the fact that one of my longtime great heroes would telephone. We often talked, and I would then ask why he phoned. “Oh, you sent me a fax three months ago…just found it.” Then we would carry on the conversation.

When we were working on the book, I got a close look at the complexity and the quirks.

For example:

“Phil, tell me a little about your relationship with von Trips, and how you got on with him.”

“I’d rather not talk about the dead.”

“Ok, what was it like co-driving with Gendebien (who was still alive at the time)?”

“I’d rather not talk about the living.”

“Phil, that doesn’t give us a lot of room to maneuver. How about Dragoni?”

“That b******! I couldn’t stand the man. He was the most difficult person I ever worked with…” etc.

“Phil, can I quote you on that?”

“I insist that you do!”

Phil, rather like Stirling Moss and Tony Brooks, among others, was a real stickler for accuracy and detail. It was in the working out and clarification of that detail that the real story came out. Phil could create a picture of an event 40-plus years ago when he told you about something that happened. I remember in the book I was mentioning Phil’s 1962 Targa practice crash. I said to Phil that I had just read John Godfrey’s detailed account of it and that I was mentioning it because it said a lot about how Dragoni operated in the Ferrari team. Without a hesitation, Phil just started the narrative: “I had felt the throttle stick open on the turn before and wondered if I had imagined it….” He went on to relate the entire tale, making clarifications of the event. It was like he was still processing that happening, making sure he got it right. You could smell the heat of the engine as he leaned over it, and see Dragoni running to the car anxious to be able to prove that Hill, and not he, had made a mistake.

Phil was tortuously analytical. One of my first opportunities to sit down and talk “off the cuff” came at the second Goodwood Festival of Speed. At the end of the day, he was waiting for his son Derek to get the car and pick him up. I was fighting the impulse to “do an interview”…to record everything he said. We just started talking about modern Formula One and I said I felt it had “finished” around 1968. He brightened and turned a casual conversation into the history of F1. He felt very much the same, but gave an exquisite, analytical view of how things had changed, what the forces were that had gone in different directions, and the weighting that sponsorship had on shifting a sport into a business. It was eloquent. I didn’t record it…which on the one hand I regret because I would like to hear it again, but on the other I don’t regret because I had the opportunity to sit and listen for no better reason than that he was doing the talking.

When I mentioned to him that he had had a good battle with Ricardo Rodriguez in the Ferrari 156 at Spa in 1962, his response was that it wasn’t a battle, and that they were “just driving close together” for a long time. Then he gave me 15 to 20 minutes on what a “battle” was in F1 and some examples…It was priceless.

Some say Phil was neurotic. I think it is more complicated than that. Phil was always one of the most thoughtful of racing drivers, and that did not always work in his favor. His talent might have been better served by being tougher and more demanding, but that would have meant him being more “confident” than he was, or more confident then he could allow himself to be seen as…if you get the meaning. I think Phil was always pretty clear about his ability, but less so about getting that across to others.

When he first went to Europe, he had subsequently said, he felt not only like a new boy but often out of his depth. He wasn’t used to the politics of professional racing then and adapting to it didn’t come easy. Had he been a more forceful person, however, he wouldn’t have been the person we came to know. He was, while racing and later, immensely reflective about the situations he was involved in. There are stories that he was rather “taken in” by the charm and persuasiveness of Carlo Chiti and his ideas of where the ATS project was going to go. Because that project, in business and racing terms, seemed to fail so miserably, many were convinced that they were right about Phil making a wrong decision to go to ATS.

Hill had gotten along with Chiti at Ferrari. He both recognized Chiti’s abilities and his shortcomings. Phil sensed that the ATS project had promise, and indeed, when first mooted it clearly did. If the proposed finance had remained, it would have gone on to do good things. The F1 car, which Phil tested again in recent years, was in many ways a clever design. The Chiti disorganization, especially when the money disappeared, took over and the promise wasn’t realized, but both Phil and Giancarlo Baghetti drove their socks off in cars that had almost no development. Sadly, the ATS season and Phil’s unsuccessful venture with Cooper in F1 tended to cloud his achievements in Grand Prix racing. It certainly didn’t help people to realize that at one point he was the most successful sports car driver, and his long-distance record—not only his wins but his ability to stay on the road when others didn’t—was remarkable. What he did at Le Mans—winning in a car that he couldn’t see out of—was nothing short of incredible.

Phil, as Denise McCluggage has pointed out, and she knew him very well, “had his greatness obscured by circumstances and his own moderate assessment of himself.” Much like Tony Brooks, it was almost impossible to get an objective opinion of just what his skills were from him, until you questioned those skills and then would come the fight back. Hill’s awareness of the complex issues which always surrounded Ferrari, and his need to be analytical about problems, made a discussion of a particular race difficult. I talked to him about the 1962 Dutch Grand Prix and what Ferrari was or wasn’t doing that year to keep up with the competition from Lotus and BRM. He found it difficult to discuss that race without laying out the entire scenario of which it was a part.

Indeed, that was the right thing to do. In 1961, Chiti didn’t want to use the inboard gearbox and wide track suspension, and argued it was slower. Mauro Forghieri wanted to use it and said it was better, without it being tested. Hill said the car was slower down the straight and aerodynamically inefficient. Forghieri said they were now doing well…the results in the nonchampionship races early in the season had been good…so it must be alright. But they hadn’t been using the car in this spec. At this point, Phil would get a painful look and say, “This is how it always was. They just wouldn’t listen to you.” The handling was better but the car was slow, and he had to duck in behind everybody to get a tow to keep up. He drove around the problem at Zandvoort, and finished 3rd, but that, according to Forghieri, indicated the car was okay. Phil was arguing with all his ability to make changes, because he knew the team was going to be overtaken very soon. Enzo Ferrari would listen patiently, and then let Forghieri do what he wanted to. It was in the later discussion of this, one could see the difficulty Phil had, not wanting to be aggressive with the team but also not being listened to. As he was not inclined to “bad-mouth” anyone, I always found I had to work out several possible answers to what might have been going on and test those out. The memories were often painful. He re-counted, as if it was yesterday, how the performances got worse after Monaco, how preparation suffered, and how times were slower than the year before.

The downturn in Grand Prix racing for Phil in 1962, which wasn’t evident to most people until well into the season, tended to eclipse how well he was doing in endurance races. And really, he shouldn’t have been. One of the problems at Ferrari was that the F1 program was suffering both from arrogance—Ferrari had gotten the jump on everyone at the start of the 1.5-liter formula and thought it would continue—and from diversification. Ferrari was now attempting to develop a wider range of sports, GT, and new road cars.

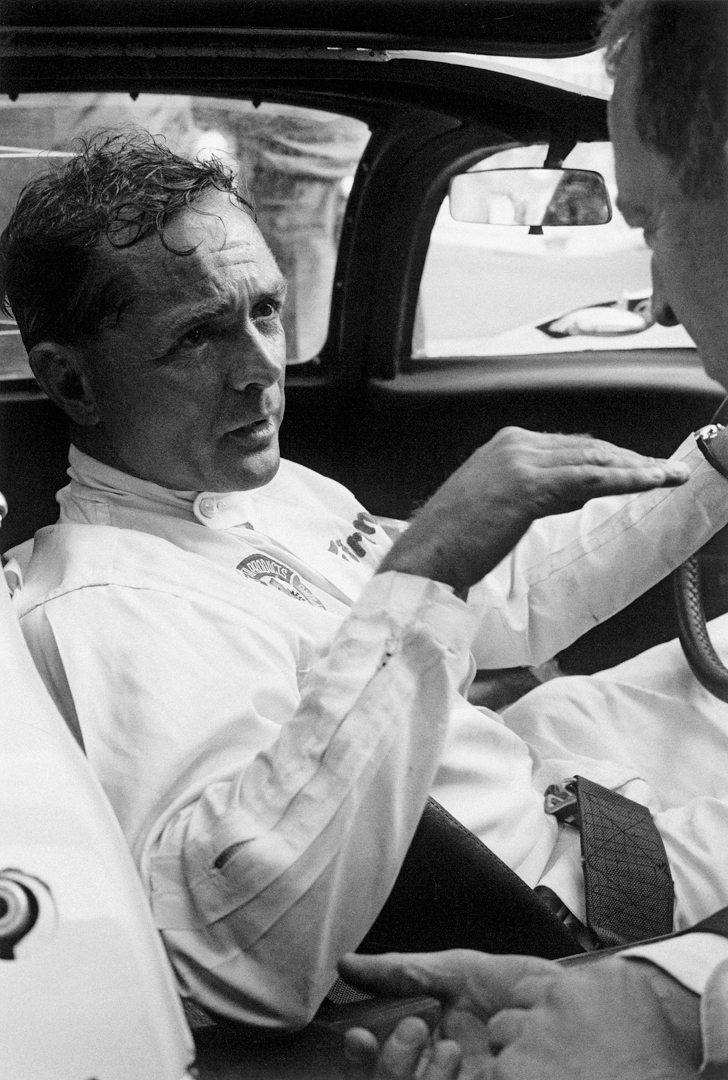

Photo: Graeme Simpson

Phil and Ricardo Rodriguez got the 246SP to 2nd at the Daytona 3 Hours behind Gurney’s Lotus 19, and then he was 2nd at Sebring with Gendebien in the Ferrari 250 GTO. That was a good result behind the 250TR of Bonnier/Bianchi. Then, of course, he had the practice accident in the 268SP at the Targa and didn’t start. He and Gendebien then won at the Ring in the 246SP, a stellar performance in damp conditions. At Le Mans, this pair reverted to a front-engine Ferrari, the 330TRI/LM, and scored a five-lap victory over the opposition. The car was virtually without a clutch for the last eight hours, yet they got it to the end…and won. While the true fans recognized just how good these two drivers were, Phil was reticent to make a point about what a great win it had been, and some tended to see Hill as less dramatic than those who drove like crazy and often didn’t finish, the Rodriguez brothers being a good example. Phil contributed considerably to Ferrari, winning the 1962 Challenge Mondiale, getting the most manufacturers’ points, and was only five points behind Gendebien while doing fewer races.

I did eventually get out of him that he was not “enamoured” of Gendebien, but agreed not to say anything at the time. The reason, in addition to Olivier’s somewhat superior manner which made some people feel inferior, purposely some said, was that at the Targa Florio in 1961, Gendebien did something that upset Phil considerably. Hill and Ginther had been talking about how difficult the then-new 246SP might be in the wet. Team manager Tavoni had taken Gendebien out of the fastest car he was to share with von Trips and put him with Phil. Gendebien heard the Hill–Ginther conversation. Gendebien was to make the start and he thought that the conversation indicated that the 246SP wouldn’t make it around, and that then Hill would be put in another car. Just minutes before the 7:00 a.m. start, the Belgian came down to the car, late, and said, “I do not take the start.” He refused to get in the car. Furious, Phil ran back to the pit, got his gear, and ran back down to the car. He usually took several minutes to prepare, but, winded from running, he jumped in and was off. He was flying, but it wasn’t long before he went off, and that was that. Gendebien got back in with von Trips and they won. Phil was left out in the country sitting on the steps of a local’s house, having a glass of red wine.

The fact that Phil, in 1961, became the first American World Champion also overshadowed his other accomplishments. The ATS and Cooper years were so difficult…in F1 terms…that there is a tendency that everything ended after he left Ferrari. I suspect that there were times when he himself might have felt that. In 1965, Honda wanted him to get involved in their F1 plans, but he declined, not having the energy. He had had enough of Grand Prix racing. He would later hint some slight regrets over this, but he certainly did other things.

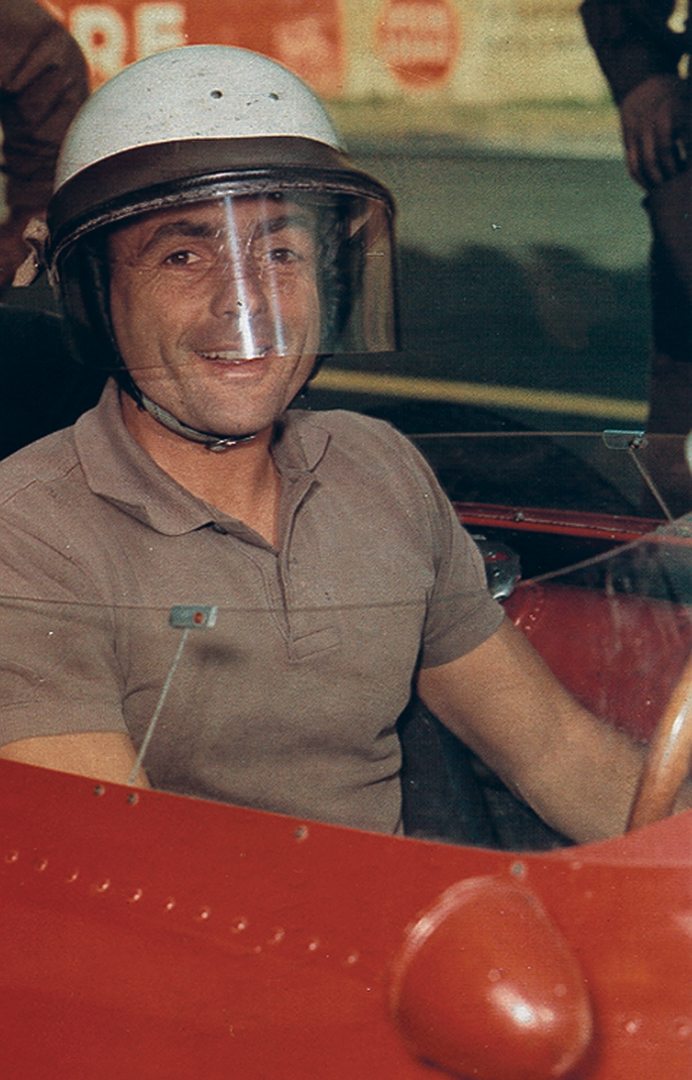

Photo: Louiseann Pietrowicz

One of my favorite quiz questions: “How many races did Phil Hill do after leaving Ferrari and ATS?”

Answer: 58, all important races between 1964 and 1967. These don’t count the historic races of more recent years.

In 1964, there were 13 F1 races with the Cooper-Climax, mostly disastrous, though he did manage a good 4th at the British Grand Prix. There was even an early 4th in a nonchampionship race at Snetterton at the start of the year in a Centro Sud BRM. But Phil also won the Daytona International with Pedro Rodriguez in a NART 250 GTO. He drove Cobras four times and GT40s five times including at Le Mans. The results were not spectacular, but he was always a front-line driver.

The following year, and here’s one few recall, he drove Bruce McLaren’s Tasman Cooper T70 in nine Tasman races, notching up a 2nd at Pukekohe and Levin, and 3rd at Teretonga, Sandown, and Longford. Then there were four more races in Cobras and three in GT40s, and finally a 2nd in one of the heats at the Northwest GP at Kent in Bruce’s M1B.

Here’s another quiz question: How many times did Phil drive a Chaparral? Answer: An amazing 17 times in 1966 and 1967. He and Bonnier had a great win at the Nürburgring 1,000 kms in 1966 in the 2D, had 2nd at the Mosport Can-Am in the 2E, and won the Laguna Seca Can-Am in the same car. The year 1966 also saw his last F1 race, when he wasn’t able to qualify the Climax-engined Eagle at Monza.

In 1967, Hill raced Jim Hall’s Chaparral 2F seven times. He found every component that could break on that be-winged machine. He came close to repeating his 1966 win at The Ring. Then came the last race of the season: the Brands Hatch BOAC 6-Hours at the end of July. Phil and Mike Spence were the masters of the swooping Kent circuit, and they took a very famous win. I know people who think that is the only time he drove the Chaparral, overlooking how much of a role he played in Jim Hall’s team. Then he decided to retire…until he came back to historics some years later.

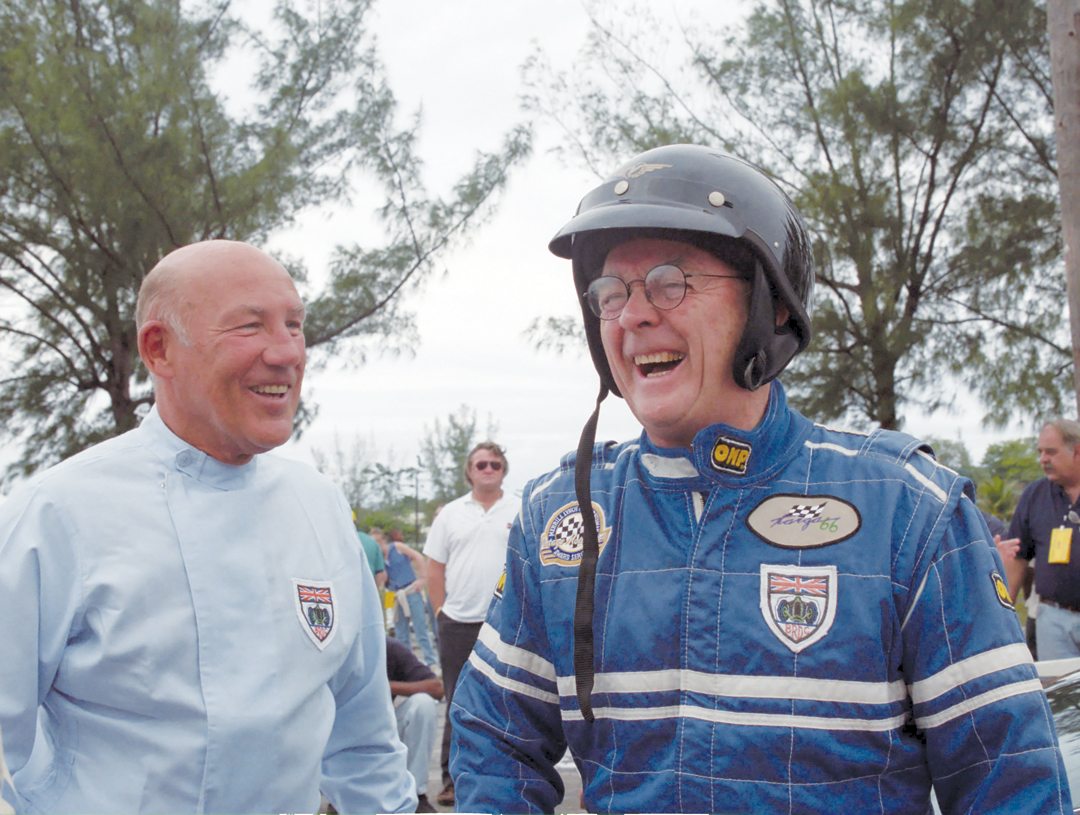

Photo: Robert Harrington

I guess I had seven or eight conversations with Phil when he showed up at the Monaco Historics in 2004 with Larry Auriana’s Alfa 6C 3000CM, one of the famous cars that Alfa thought would dominate endurance racing in 1953. Phil said to me, “You know about this car?” He remembered that I had written about it and my connections with the marque. He said, “It shouldn’t really go well here, should it?” But when he came in from practice, he was 2nd fastest, slicing around the street circuit in a style that made many think someone else had taken over the car. There were a few telltale scratches down the side. He was sitting in the corner of the pit garage with the car owner. There were unaccustomed smiles all around. Phil wanted to talk. Moss came over and there was a lot of banter…and rivalry. Stirling in the C-Type was going well, but not as quickly as Phil. The jibes were gentle but meaningful. There were Moss and Hill…on top form…racing their hearts out. We did some interviews for the local Monaco English-language radio station. I had never seen either one of them in such a good mood at a race meeting. It is an enduring memory.

Three or four weeks later, the phone rang. The unidentified voice said, “That Alfa was good wasn’t it?” Great guy.