Last month we ran the first half of the tale of Hal Crocker’s relationship with Peter Gregg, encompassing the early years of Peter’s racing career. This month Hal tells the rest of the story.

Photo: Hal Crocker

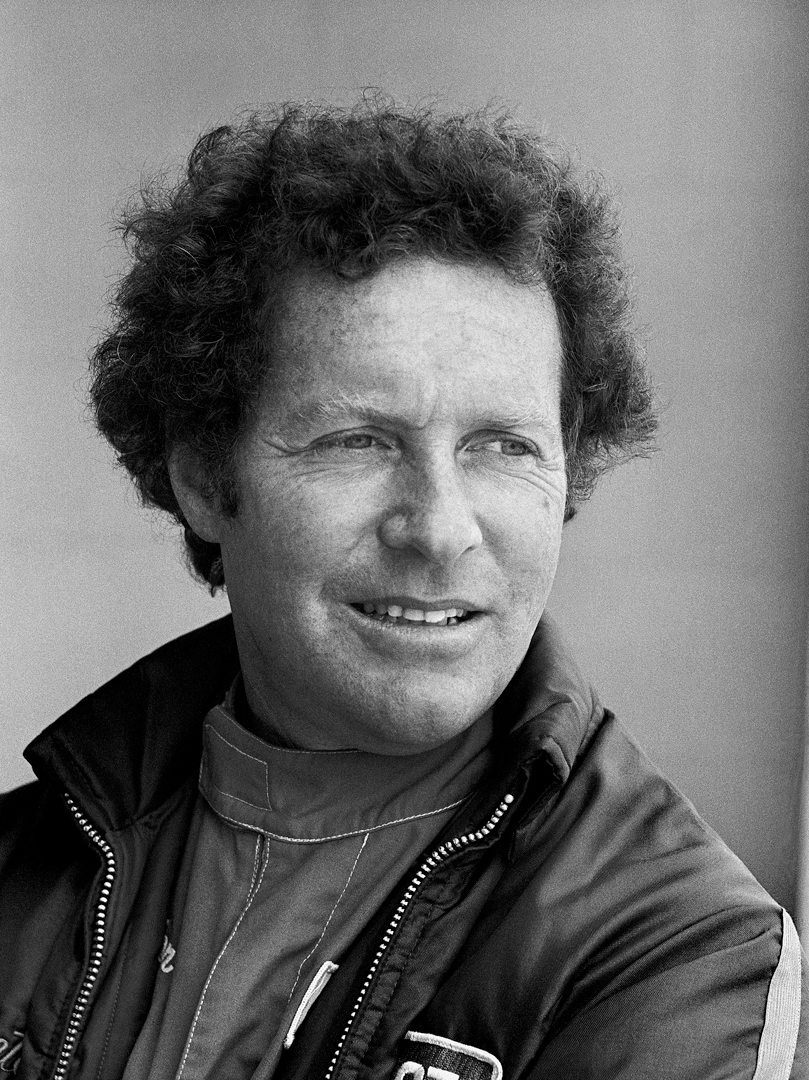

Being a photographer himself, Peter Gregg was appreciative of my skills. At the first Can-Am race at Road Atlanta in August of 1970, Gregg hired me to do some photography. While doing posed shots, Gregg made a point of telling me that he had seen my wife Annelies with Peter Revson. I asked him if he wanted to keep the bandana around his neck on for the shots and he said yes. I then asked him if he wanted me to wait while he got his John Deere hat. He took the bandana off.

It was during this same shoot that Gregg accused me of loving the Germans. I asked him why he thought this. He reminded me that I drove German cars, shot Leica cameras, had a darkroom full of German equipment, a German Shepherd and a German wife. I told him he was mistaking respect for love, and that my wife was actually Austrian and she would be going home with me since Revson was too short for her taste. Gregg and Revson were about the same height; this was not lost on Gregg.

It was during this conversation that we moved to the subject of ladies. Gregg asked me if I preferred European women to American. I asked him if my preference was not obvious since I was married to an Austrian. He gave me a left-handed compliment by telling me that I married out of my league. I told him he should know about marrying out of class, touché. Gregg made an interesting observation that I have thought about a number of times since. He said that as long as the lady is not repulsively ugly you grow accustomed to her looks quickly, whether she is a five or a ten, and that it is the person you fall in love with in the end and not the beauty. This surprised me because I thought Gregg too superficial and self-centered to have such a philosophy, but thinking about it, I agree. Then again, I never saw Gregg with an unattractive woman, and I saw him with quite a few.

Gregg had a real nice-looking Lola for this event. Looks were deceiving in the case of the Lola, however, as Gregg thought the car evil and hard to drive. He told me the car scared him. I was surprised by this admission, but what really surprised me was Gregg buying a Porsche 917/10 shortly after this. If the Lola scared him, what the hell was he thinking buying a 917? In actuality the 917 was, for the most part, a good-driving car and Gregg liked it until he put the turbo engine in it. Maybe it was part of a new business plan or maybe he needed more stimulation to get the adrenalin rush. Another “what was he thinking” moment that year came when Gregg opened a dealership called Sport Auto selling MGs and Fiats after telling me a few months earlier that he wanted nothing to do with selling cheap cars. This now gave him three car stores and a full racing schedule.

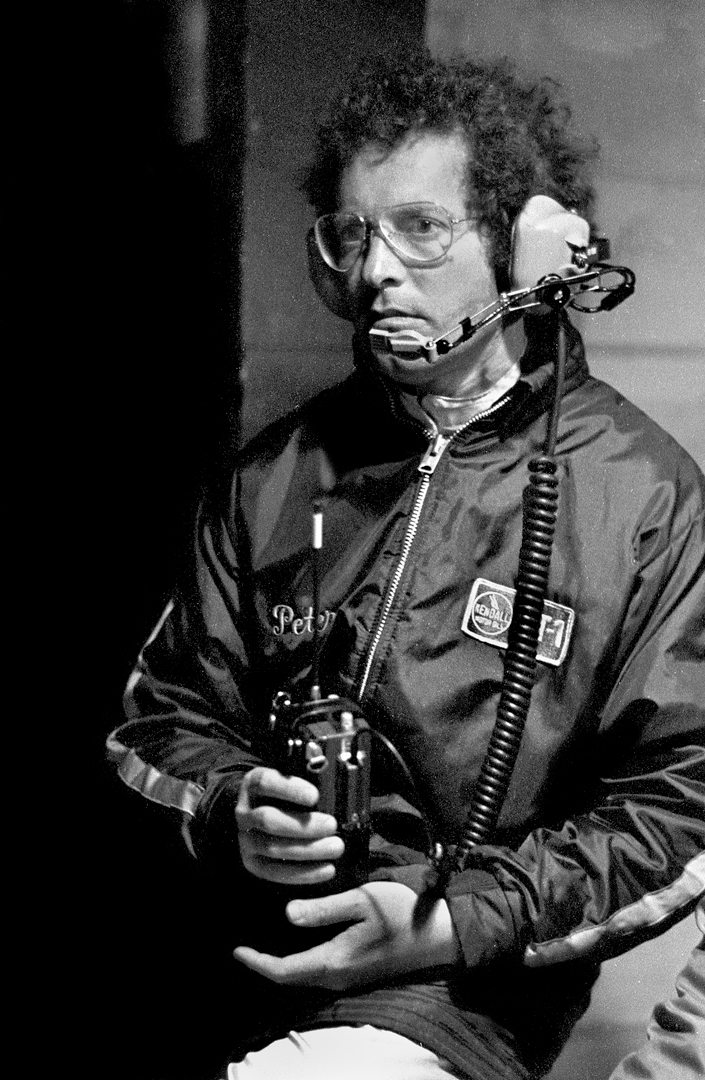

While I spent the better part of ’71 in a VA hospital, Gregg was driving a Bud Moore Ford Mustang in the Trans-Am and helping Hurley Haywood win the IMSA GT Championship in a Brumos Porsche. At Daytona in February of ’72 I weighed in about 50 pounds light due to my hospital time, and Gregg seemed sincere with his concern for my condition. I equate it to having concern for good hired help; Gregg did not want to lose his favorite photographer, even if he did have a bad attitude.

Photo: Hal Crocker

Running the 917 in the ’72 Can-Am was Gregg’s main focus for the year. For all his effort he finished 9th in the championship and won $25,700. Gregg told me, “It don’t make shit for sense business-wise. I’m afraid to do the books. I spent over a million on the season.” It did not take a Harvard education to figure out that Gregg’s Can-Am program was a money-losing proposition. The old adage, “How do you make a small fortune in racing? Start with a large one,” comes to mind. Besides, Gregg was falling out of love with the car since he put the turbo engine in it. Remember that neither he nor Haywood had any real turbo experience at this time. Gregg crashed the car at Edmonton and sent it straight to Dave Kent to get fixed and painted. To my knowledge he never drove it again; instead he sold it to Haywood telling me that Hurley had the right mental aptitude to race it.

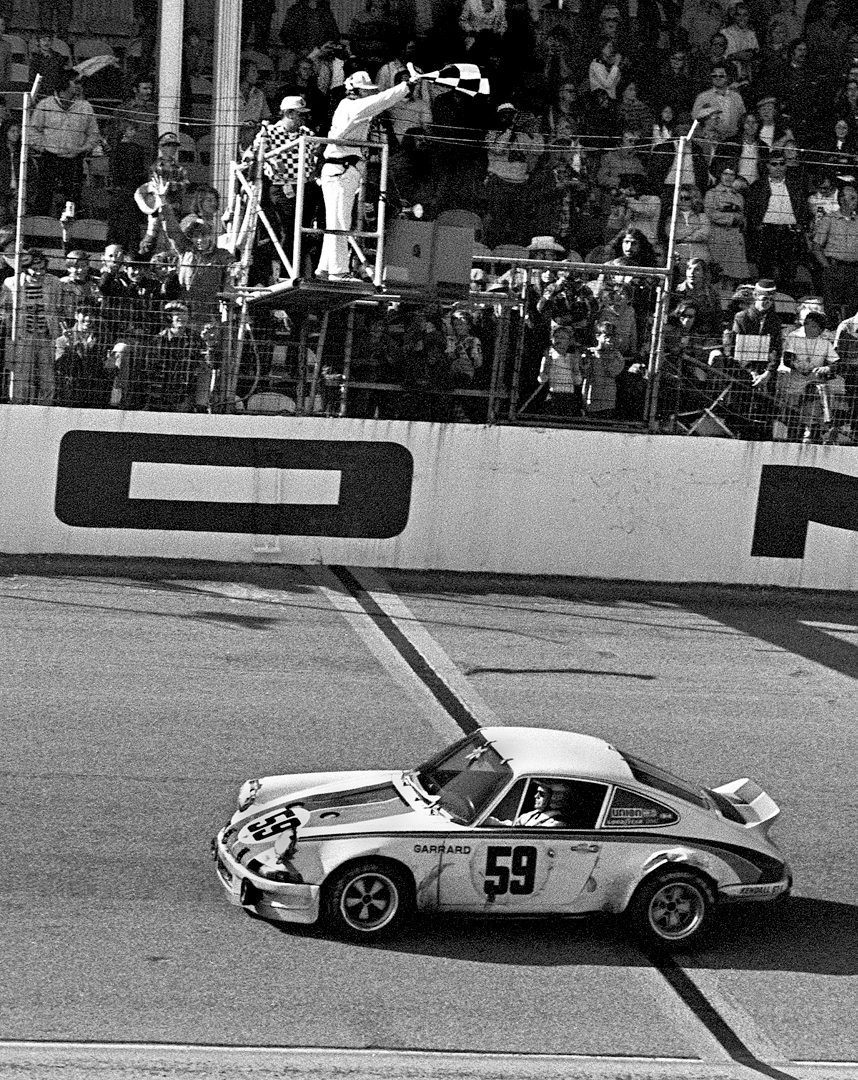

We were at Daytona for the last IMSA race of the 1972 season when Peter chirped, “That’s a good looking car, don’t you think?” The car in question was a rust primer orange with black numbers. He asked so I gave him an honest answer, “It looks like shit and photographs worse.” Peter responded, “What’s wrong with it?” I started to itemize. It was a brutal critique followed by an awkward period of silence. Peter finally broke the silence and asked, “If it was your car how would you paint it?” So I told him. We were both ex-military and patriotic, plus Gregg had ambitions of racing in Europe, thus the red, white and blue. White being the bottom layer because at the time most photography was still done in black and white and white was good for low light. The red and blue were to be only accents laid on the white. It would be a simple scheme for ease of maintenance. After about an hour of how and why, I agreed to send him a comp. I used my darkroom enlarger to project images of a 911 onto art paper and then sketched out the graphics on the car and sent it off to Gregg.

Photo: Hal Crocker

At the next race, the 1973 Daytona 24 Hours, there it was. A white Porsche 911, numbered 59 with red and blue trim, just as I had laid it out. Gregg saw me and came over, “Well how do you like it?” “Great!” I said. I think my grin equaled his. I was thrilled with my first racecar graphic design project. There was no verbal communication of the fact, but we both knew a truce of sorts had been called.

For this race both Gregg and Roger Penske got 911 RSRs from the factory. The cars were identical except for color; Gregg got a white one while Penske’s was dark blue. Gregg flew Dave Kent, who had done the BRE Datsuns for Peter Brock, into Jacksonville to do the new red-white-blue motif. Though I did not get paid for this project it led to Jo Hoppen sending me some graphic design work and doing a class for Porsche on how to paint a racecar as part of a two-day seminar Porsche provided to its teams at Daytona. The simple red-white-blue scheme survives to this day and has run more race miles that any other scheme I know of.

Jack Atkinson, having experienced loose flywheel bolts due to harmonics with a similar engine, applied his special mix of green Loctite with hardener to the bolts to ensure they stayed in place. The story goes that Atkinson told Woody Woodard, the crew chief for the Penske car, and Gregg passed the information on to Penske himself, but both discounted it because they suspected Gregg was playing head games. During practice the Penske car lost its flywheel, and in the race went out due to an engine problem in the middle of the night, while Gregg and Haywood won. I can’t help but wonder if the engine was damaged when they lost the flywheel.

Photo: Hal Crocker

This was a big win for Porsche because it was the first international win for the 911, but it was even bigger for Gregg and Haywood for it moved them into a number of new categories and a very elite club of 24 Hours winners. The best payoff for Gregg, however, was the fact that he had beaten Roger Penske. I think that this played into him announcing his retirement. Gregg told me, “I want to get off when the elevator reaches the top floor. I don’t want to make the mistake that so many drivers make and ride it back down.” In his retirement announcement were his plans to take over as the director of The Jacksonville National Bank. Gregg told me he was going to trade his helmet in for a tennis racket and live the country club life. This retirement would be measured in days if not hours.

It was at that race that I met Bob Snodgrass, a big burly guy with an infectious smile. He was dieting to lose 25 pounds and trying to break the smoking habit at the same time. He reminded me of a Cocker Spaniel on crack cocaine, friendly but not well focused. This dieting would be a lifelong losing battle. He was from Elmira, New York, just down the road from Watkins Glen where, as a young lad, he got bit by the motorsports bug. Though he fit in at the dealership, for the most part such was not the case at the racetrack. Astute members of the media were fast to get his scope and learned to do an end run around him if they wanted the facts and not the truth according to Snodgrass. The race crew called him “The Hubcap Manager,” and this was not a term of endearment. He had come to Gregg by way of the Fiat importer, where he had been the parts and accessory sales guy, thus the moniker. Later it was shortened to “Hubcap,” the explanation being that he went around and around looking good but serving no real purpose.

Snodgrass started at Gregg’s Sport Auto store as a salesman and soon moved up to the Porsche store before becoming Gregg’s most trusted confidant. He was primarily a car salesman, and this craft gave him the skills to tell Gregg what he needed to hear to keep him balanced. He was like the tail on Gregg’s kite. He would come to know Gregg’s darkest secrets and what it’s like to deal with a bipolar manic-depressive on lithium. He would suffer Gregg’s test right to the end, but would get revenge by writing the history of Brumos according to Snodgrass. Snodgrass died in his sleep in April of 2007 from a reported heart problem. Snodgrass is missed by many of us, for in spite of his shortcomings he did bring a lot of levity to the game.

Photo: Hal Crocker

Atkinson laughs as he tells me that after the race the winning car went back to the factory and shortly thereafter he received a Telex from Norbert Singer, head of the Porsche Racing Department, asking how to get the flywheel off. Singer, better than anyone, knows how much Atkinson and Gregg contributed not only to Gregg’s program but also to the factory’s.

Always Seeking The Edge

Atkinson tells me, “Peter always kept up with NASCAR and Indycar racing, looking for ideas that would work for us in sports car racing,” and provided a list of examples:

“1973 24 Hours – first two-way radios, borrowed from Bobby Allison;

’74 – first RSR front oil tank with a 1-1/4 inch diameter oil inlet line to prevent cavitation leading to rod bearing failure;

– first use of repeater for long-range radio communication;

’75 – radical rear fenders for downforce without drag, a big help at Talladega—led to lawsuit between Peter and IMSA;

’76 – first air jack system—idea from Indycars, huge advantage for pit stops, especially dry-to-rain/rain-to-dry;

’77 – 934.5 corrected “turbo lag” by changing throttle butterfly opening direction;

– used 935 transmission with titanium spool and axles;

– moved shift lever up next to steering wheel for faster shifting;

– adapted chassis to fit 935 nose—ran Mid Ohio as a 935;

– used dry ice to cool fuel before start and to cool refueling rig, allowing one stop less in a three-hour race. Won by over a lap;

’78 – vacuum system using an AC compressor to retract the brake pistons for faster pad changes;

– airflow through front oil cooler directed to front wheel arches, giving much better front downforce;

– reduced front caster to 1-1/2 degrees for easier steering;

– swapped front hubs to change tightening direction for wheel nuts to keep them from loosening under braking;

– additional torque on rear axle nuts to stop flexing that had caused pad knock-back and loss of brake pedal;

– fly-cut exhaust valve notch on piston top to build in over-rev safety as turbo engine’s exhaust valves ran too hot to stand any interference;

’79 – moved rear suspension pickup points to correct anti-squat and roll steer—we were running the cars so low that we had lost some vital settings;

– turned the transmission upside down to improve axle alignment—again because we were running so low with the chassis. The ’79 car won nine races out of 15 entered, it was a great car, but was really at the end of its development.”

Photo: Hal Crocker

I can feel the pain in Jack’s voice when he tells me that he really hated to have to tell the factory how he engineered the turbo lag out of the 935. “This was quite an advantage and was winning races for us,” he explained. By agreement, however, the factory got to share in anything that Gregg’s team learned or developed. I’d known that Gregg was smart and crafty, but after talking to Jack I have a new respect for just how much.

A few weeks after Gregg announced his retirement he was at Sebring, driving with Dave Helmick and Haywood in Helmick’s brand-new, just-off-the-docks factory-prepared Porsche 911 Carrera RSR that Gregg had sold him. Peter tells me he is thinking about going NASCAR racing. This brought a smile to my face. Gregg made the best of coming out of retirement by winning the Sebring race with Haywood and Helmick. It was the first time anyone had won the 24 Hours of Daytona and the 12 Hours of Sebring back to back.

Living the dream, Gregg went NASCAR racing in May. It was for only one race, but he did it. He qualified and started 7th in a Cotton Owens Dodge for the 1973 World 600 at Charlotte. Who would ever have thunk it? Gregg made it all the way to lap 28 before crashing out and becoming the first caution of the race. Neil Bonnett, with a smile on his face, told me that he didn’t think NASCAR was Gregg’s thing. Another good ol’ boy added, “He didn’t like you rubbing on him.” No, NASCAR was not Gregg’s “American Pie.” He would not be going to the levee and drinking whiskey and rye with these good old boys. NASCAR was another of Gregg’s piss-poor business plans; Gregg collected a whole $775 after spending over $50,000 for this one-off effort, while Buddy Baker collected $27,200 for the win.

Photo: Hal Crocker

At Lime Rock that September Peter made a point of introducing me to his brother Jonathan, who was an architect living in Vermont. I remember that Peter was very generous with the accolades in the introduction. Stanley Kubrick would have been flattered. This was “Charming Peter,” so charming that I went into full alert. Was this big brother showing off for little brother or was it “Nice Peter?” You just never knew.

The year 1974 brought the resignation of Richard Nixon, the great gas crisis, economic recession and panic in the motorsport community. The Daytona 24 Hours was cut to 6 hours and Sebring was cancelled. Where there is calamity there is opportunity, however, and Gregg seized the moment to win the Trans-Am championship, while at the same time taking his philandering to a new level. Though Gregg would get off to a good start for 1975 by winning the Daytona 24 Hours, ’75 would mark the beginning of the end for him.

He crashed out in Sebring. He would instigate and lose a lawsuit with IMSA. The big marker for the year, however, was Jennifer leaving him after catching him with another woman. At first Gregg was very blasé about the whole thing. He told me it was just a temporary separation and they would be reconciling. I don’t think it was the betrayal or humiliation as much as the taste of freedom, but Jennifer was tired of Gregg treating her like a rodeo pony. She was now free of him, and had no intention of returning to the abuse. With his “Band-Aid” removed, Gregg’s life started to crack and crumble.

The rebuff from Porsche was probably partly responsible for Gregg going to BMW for 1976 season. Gregg exhibited prowess negotiating the deal, making the Jacksonville BMW franchise part of it. In 1977 Mercedes-Benz felt there was a conflict with Gregg having a BMW dealership competing against their brand. Gregg’s solution to the problem was to go to Skip Gwinn at another dealership down the street and propose to give the BMW franchise to him. Gwinn, though, was not in a position to do the deal, so Gregg gave it to Tom Bush. Today Bush has two dealerships in Jacksonville worth a considerable sum.

Now out of the BMW business, so to speak, Gregg returned to IMSA with a Porsche 934/935 hybrid. When the hybrid showed up for its first race, Charlie Rainville, IMSA’s Chef Technical Inspector, took one look at the new creation and promptly outlawed it, though he did give Gregg high marks for creativity. Gregg picked up his marbles and went to play with the SCCA in the Trans-Am. After the last race of the season it appeared that Gregg had won the 1977 Trans-Am Championship—until Ludwig Heimrath, a Canadian Porsche racer, protested Gregg’s car for missing two bumper supports. Atkinson had modified the front of the car to accommodate quick changes of the nose. It was not a weight issue, the car made weight. It was what I would describe as a Mickey Mouse protest, one contrary to the spirit of sportsmanship. In my opinion, men of integrity would not participate in such for there is no honor in such a win.

Photo: Hal Crocker

After politicking long and hard, Gregg got invited to participate in the newly reformatted IROC VI. On October 14, 1979, he won the Riverside IROC round in a Chevrolet Camaro. From Gregg’s perspective, this may have been the zenith of his racing career. He led from flag to flag ahead of a lineup of open-wheel racers, with four F1 World Champions in the mix. To describe Gregg as manic would be an understatement, never mind the fact that he had what the other drivers called the fast car. IROC tried, but never could get all the cars equal; oh they got them as close as humanly possible, but not identical.

It was during this manic high that Gregg told me he was thinking about selling everything and moving to Italy and driving Formula One for Ferrari. I had heard this before. I told him that I was thinking about joining NASA and going to Mars. No sooner had I said it than I wished I hadn’t, because I realized that Gregg had reached a new mental stage, he was now delusional, he believed this to be feasible.

Gregg was still riding the high from Riverside—and his IMSA title—at the IROC finale, which ran as part of April’s Atlanta 500 NASCAR weekend. Gregg and I were sitting on pit wall with a number of other drivers while the sweeper was cleaning the track. A crew was staging a NASCAR right in front of us. On the rear pillar was a decal that said something like “Jesus is my co-driver.” As the driver was about to get in Gregg called out, “You ever think about letting your co-driver take it around for a few laps?”

This put down on religion was not lost on the good old boys, most of whom attended services at the track every Sunday. Gregg would end his IROC career that weekend by being involved in the big crash. Mario Andretti, who I put in my top three, without hesitation, took full credit for wiping out Gregg and all but four of the other cars. This is another story.

The Beginning of the End

Le Mans is without a doubt my favorite race, but getting there can be as dangerous as the race itself. I had my first car accident on a French highway in 1965. I took to the shoulder and clipped a post avoiding a five-car accident. Back then, priorité â droite, traffic entering from the right had the right-of-way. Now yellow diamond signs mark highways that have the right of way, but old habits are hard to break. In June of ’80, Gregg was to drive a factory 924 GTS at Le Mans with Al Holbert. Gregg and American painter/artist Frank Stella were heading to the track in a Porsche press pool street car when a farmer on a tractor pulled out from the right. In the ensuing accident, Stella was not hurt badly, but Gregg suffered a head injury that left him with diplopia (double vision) and headaches.

Mike Colucci, Gregg’s longtime friend and race mechanic, tells me that after the accident he could instantly tell whether it was “Good Peter” or “Bad Peter” he was meeting with. “The two Peters took on totally different personas,” he says. “If Peter drove up in his Mercedes and was in business attire, this was ‘Good Peter,’ but if he came up in his Porsche wearing shorts, topsiders, his Martini Apennine cap and unshaven, this was ‘Bad Peter.’”

During November of ’80; I was down for the traditional IMSA Daytona finale. I had gone down a few days early to do a photo shoot for Bob Penrod who had bought the old Plaza Hotel and was doing a major renovation. It was still early in the week when I went to the hotel bar to meet a friend with whom I was having dinner. I had just entered the bar when I heard my name; it was Gregg calling me. He was sitting at a table with a lady. After more than adequate time for an introduction I introduced myself. It was Bad Peter being an ass. The lady’s name was Deborah Marrs.

I was familiar with the Mars family and the Mars Candy fortune, for a friend had once dated one of the Mars girls, so I assumed that Gregg was going for money. I was wrong on two counts; the name was Marrs, not Mars, and she was not of wealth. The week before the meeting at the Plaza, Gregg had proposed marriage to Becky, an Eastern Airlines flight attendant friend of mine based in Atlanta. Becky was an attractive lady, what we call “a looker;” in fact, she had been in the Miss America Pageant one year, but Gregg had never seen her when he proposed, only talked to her on the phone twice. I remember Becky coming into the darkroom and informing us that Gregg had proposed marriage to her. Later that night we raised our glasses to toast the powers of Becky’s charm.

Of course, she had no intention of accepting. Becky’s rejection of Gregg became Deborah’s good fortune, so to speak, for she and Gregg would marry on December 6, a few weeks later—after a day and night of Peter’s brother Jonathan and a number of friends trying to talk him out of it. Nine days later, at the speed of a bullet, Deborah would go from being the bride of a manic-depressive on lithium to a very wealthy widow.

For the Daytona finale Gregg had a brand-new, super-trick car that, in fact, was a rebuild of a crashed car. Gregg thinking that he was an engineer and smarter than he was—an error he should have realized by this point—designed what is called the 80 car. This was a car that Atkinson built using Gregg’s design ideas and the latest factory and custom parts. The car had a Joest tail and a 1980 trick Porsche factory nose. Atkinson warned Gregg that the Ackerman angle was wrong, but Gregg ignored the warning since he did not know what the Ackerman angle was. Atkinson had the car ready for testing in August.

Gregg, still in recovery from the Le Mans accident and still mad at Haywood for the loss of their last race, hired Al Holbert to test the car at Daytona. Gregg had special sunglasses at the test to help with his eye problem and headaches, but they seemed to be of little help for he would go and lay down at every opportunity. Holbert reported that the car was diabolical and needed some serious re-engineering. The team was almost packed and ready to go, Holbert was taking a few last laps when coming through NASCAR 4 he hit the bump over the tunnel and lost the car. At this point a car is almost at terminal velocity, and it ricocheted off the outside wall and back across the track, hitting the inside wall and coming to a stop at pit-in. Holbert walked away from the wreckage but the car was destroyed. The team worked hard to rebuild it for the final race of the season.

Hoppen wanted a full photo documentation of the car for the factory to look at. On the race weekend, as the crew worked on the car, Gregg and I made small talk outside of the garage. As Gregg reached into his pocket he said, “You know I’m crazy?” I said, “Yes, I know.” He pulled out a small plastic container. As he poured out little white pills into his hand he said, “No, I’m not kidding.” Gregg pointed to the pills and informed me that they were lithium. Then he asked if I knew anything about lithium. I told him that it could easily mess up his electrolyte balance if he was not careful. He told me that he could not continue to take them for they dulled him out too much. We were interrupted by one of the crew; he was needed.

Photo: Hal Crocker

I felt for Gregg. I actually knew quite a bit about lithium from Dr. Harley the Army psychiatrist, as well as from an up close personal experience with a long-time friend. Dr. Harley did not like to use this drug, and only did so when he ran out of options. My friend had the same complaint as Gregg, and told me that he’d rather be dead than on lithium. My friend was able to self-rescue by using an extreme exercise regimen that he continues to this day. At least Gregg was seeking help and that was good, or so I thought.

That was the last time I talked to him.

Gregg took the car out, but could not turn a good time. Atkinson told me Gregg said nothing on the radio for the few laps that he did before returning to the pits. He was so frustrated that he had the team load the car and head back to Jacksonville. I have been told that a misinterpretation of German to English of thirteen for thirty on a suspension setting was a major factor in the problem. Even Mario Andretti could not have turned a good time with this car as it was set up. Gregg would go winless that season, something he hadn’t done in all his years of racing.

At this time Myrtis Howard was not only Gregg’s personal secretary, but also second in the chain of command at Brumos. She had been with Gregg from the very start, and they had been through a lot. Their relationship was more like family; they cared for each other. A better analogy might be a mother grizzly and her cub, for her office was just outside Gregg’s and she controlled access to him. Her voice cracks when she tells me about the last day Peter came into the office: “He went into his office and laid his head down on his desk. He had never done this before. When I went in, he told me that he was depressed and could not pull out of it. I tried to help, but nothing I said seemed to have any effect.”

This was Friday December 12. The next day Gregg invited Haywood for lunch at his house, and during lunch reminisced about their relationship. He asked if Hurley thought he had made a mistake in marrying Deborah and Haywood answered, “Yes!” Gregg invited Haywood to a basketball game, but Hurley already had plans for the night and declined. Gregg’s two sons came in and Gregg invited them, but they also had plans and declined. Haywood left, followed shortly by the sons. Deborah later told Haywood that Peter just rolled up in a blanket on the couch.

Photo: Hal Crocker

Going south out of Ponte Vedra on Florida State Highway A1A one comes to the intersection of Mickler Road and State Highway 203. If you turn left onto 203 and go about two-tenths of a mile, the road takes a left and heads north along the beach. If you go straight instead of turning north, there is a parking area and a break in the sand dunes to the beach. This is Mickler’s Landing.

On the night of June 16, 1942, the German submarine U-584 landed four saboteurs on this desolate beach as part of Nazi Germany’s Operation Pastorius. The mission got compromised and the four were captured and executed as spies.

On the afternoon of December 15, 1980, Peter Gregg made his way there with his briefcase. Not a whole lot had changed with Mickler’s Landing in 40 years; it was still somewhat desolate. He sat down on one of the dunes among the sea oats, took out a yellow legal pad and wrote a note:

Dec. 15th 2:30 p.m.

Debbie –

First, I love you, and this isn’t related to you. I don’t want to live with my life-long illness of driving everything away, with making myself and others miserable.

Please don’t feel you are partly responsible—you are not. Try to have a happy life. I’m no good for you in the long run.

Jason & Simon – Forgive me. I just don’t enjoy life anymore. I must have the right to end it.

Jennifer – You helped me more than anyone. You shielded me from despair for years. Thank you.

Bob S. – You’ve been so wonderful to me. I want you, Myrtis and Siggy to own auto business with Debbie.

Debbie – please honor my request about Bob getting to own car dealership.

I don’t feel crazy. I have done all I want to. That’s it.

He then took a .38 Special, put the muzzle to his head and pulled the trigger.

Dallas Gunn, race team owner and wife of racer John Gunn, phoned the next morning and asked if I had heard about Peter Gregg. I responded, “He’s dead,” and she said, “Oh, you have already heard.” I said, “No, what happened?” Somehow when she asked the question my subconscious knew the answer. I thought: what a waste; and felt a note of sadness and loss.

I have thought about Gregg’s final solution. It has been the subject of a number of conversations with racing friends, and I think about it every time I see an old rerun of M.A.S.H. and hear the theme song, “Suicide is Painless.” I have heard that suicide is the ultimate “Fuck You!” Sometimes, yes, but not always. If you have never thought about suicide you have lived a charmed life. I thought about it when I was in the military. We knew what the other side did to Special Forces guys who got captured. I decided that my last bullet was mine. Then when I was in the hospital I thought about it every time the morphine wore off and I waited for the clock to run and prayed that the nurse would not be late with my shot.

Photo: Hal Crocker

Pain comes in many forms; I suspect that Gregg suffered his share and in many varieties. On Gregg’s seventh birthday his mother committed suicide by stepping off a subway platform into the path of a train. This was so painful that Gregg kept it a secret, a secret that Jennifer did not know until after his death. Jonathan, Peter’s brother, tells me that for the next few years after his mother’s death, their father hired a new housekeeper every year from a different country so they could experience different cuisine and culture. Gregg and his siblings would grow attached to these caregivers only to have them taken away. At 12 he went off to boarding school. At an early age Gregg learned what it was like to lose people and connections that he cared about. In conversation with Gregg about Jo Bonnier and the movie Le Mans, he gave me the impression that he considered all relationships temporary. He said in the end we lose everything and everyone. I think that Gregg developed a defense mechanism, and part of that was that he did not want to make or have friends for fear of them disappointing him or him losing them.

The year before Gregg’s death Susan, his only sister, was dying of cancer. He dealt with this by ignoring the whole situation. He never went to visit her, nor did he attend her funeral. He lost his identity of race driver to diplopia. He lost Jennifer, who I believe was the only woman he ever loved. His world was coming apart and he had lost what little control he had. He was a man in pain, and knew that modern psychiatry and lithium were not the answer. I judged Gregg on many things, but I do not judge him on his final act.

A few weeks after Gregg’s death I was on my way from Atlanta to Daytona for the start of SpeedWeeks when I decided I needed to see Mickler’s Landing. When I left Atlanta I had no thoughts of doing such, but somewhere around Valdosta the thought took root and the closer I got to Jacksonville, the stronger the call.

I remember it was cold and misty as I stood looking out to sea and drinking my coffee. The hot cup felt good in my hands. There was a seagull reconning me with a suspicious eye. He hung almost stationary on the ocean breeze just a few feet away and stared me straight in the eye. Then I realized it was the Danish that I was eating that had his eye. I broke a piece off and threw it in the air; he got it only inches from the ground. I called out, “Way to go Fletcher.” Fletcher was the seagull in Jonathan Livingston Seagull, a New York Times best seller back in the early ’70s. I was impressed; I had it at long odds that he would make the catch. Now back on the breeze and even closer, Fletcher looked me again in the eye, but this time I read defiance and a challenge behind his eyes. I answered with a throw that I thought was mission impossible, but again he executed an aerial maneuver to perfection and defied the odds. My mind raced. Was this gull a messenger from the gods? In Livingston’s fable Fletcher was a seagull on a quest for knowledge and self-perfection, somewhat of a parallel to Peter Gregg. How ironic, this coincidental connection with this seagull on this day and of all places where the story ends. Yes Peter, it says “No Preference,” but I believe in a power and something beyond this world.