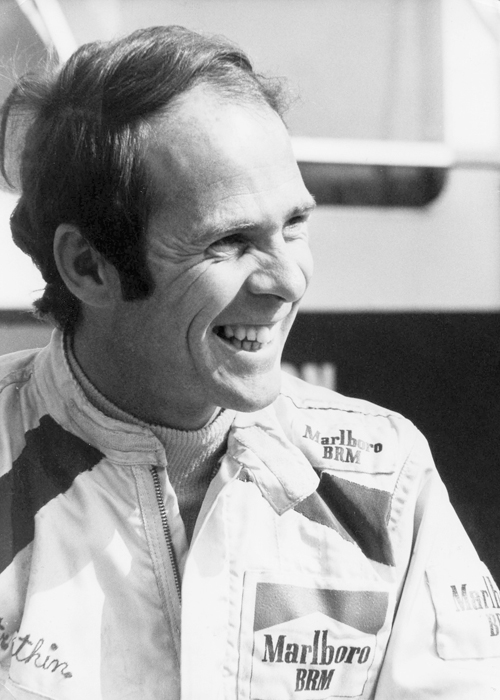

Peter Gethin may have been the son of a jockey, but he pursued a different kind of horsepower, making his name racing automobiles. They weren’t just any automobiles either, but the fastest most prestigious racing cars in the world. He was a race winner in Formula 1 and the original Can-Am, and a champion in Formula 5000. His first major recognition came in the mid-’60s when he raced in the British Formula Three championship, and by 1969 he was winning races on his way to the title in Britain’s new Formula 5000 series. He repeated that feat in 1970, the same year he also won the Formula Two outing at Pau, the Can-Am round at Road America, and contested seven GPs for McLaren after being drafted into the F1 team upon the death of founder Bruce McLaren. By midseason in 1971, however, he’d switched to BRM, taking the place of another casualty—this time Pedro Rodriguez—and proceeded to win his second race for the team at Monza, at that time the closest finish and fastest race in F1 history. VR’s Mike Jiggle recently spoke with Gethin about his time in the sport.

Photo: BRDC Archive

Many will remember you for your exploits in Formula 5000 and your remarkable victory for BRM at the 1971 Italian GP, but where does the Peter Gethin story start?

Gethin: I started in a Lotus 7 in the early 1960s, I did a few races mainly at Brands Hatch. For 1963 I ran a Lotus 23 for myself, and the following year I won the Guards Championship for cars up to 1100-cc. In 1965, I did Formula Three with Charles Lucas, Piers Courage and Jonathan Williams. I did Formula Three again in 1966 and ’67 with Sports Motors of Manchester, Rodney Bloor. In 1968, I raced Chevron sports cars and Formula 2 for Frank Lythgoe Racing. Our Formula 2 Chevron B10 wasn’t quite as good as the Brabham BT23C that always seemed to be there or thereabouts, so we changed toward the end of the season for a BT23C. My 2nd place behind Henri Pescarolo’s Matra at the Grand Prix d’Albi in late October was the result that, I’m sure, got me into Formula 5000 for 1969. Late in 1968 or early in 1969, I can’t really be sure of the exact timing, Formula 5000 came out. McLaren approached me, or maybe I approached them—again I’m not too sure, but we got together. They found Church Farm Racing, who were prepared to run the car, and we competed in the inaugural Guards Formula 5000 championship. I did all the testing over the winter months with Bruce McLaren.

Mike Earle of Church Farm Racing recently told me that during the late ’60s and early ’70s some of the best drivers in the UK came from within a 20-mile radius of Bognor Regis. Derek Bell, David Purley, John Watson, yourself, do you think there was something in the air around there, or was it pure coincidence?

Gethin: I think it’s like saying Scotland was a “hot spot” for Formula One drivers since Jimmy Clark and Jackie Stewart came from there. No, I think it was due to the close proximity of Goodwood Motor Racing Circuit.

That first season in Formula 5000, you did a few races where you were successful, and then you went to America for their Formula 5000 championship. You returned to the Guards Championship later in the year and won it. Why did you move to America, did you find the challenge too easy over here?[pullquote]

“Do you really want to become a racing driver, if so how much? Would you kill for it?”

[/pullquote]

Gethin: We started with the best car on the grid, the McLaren M10A. We’d more or less won the championship by the halfway point of the season. Financially speaking, we felt there was a better market over in the States and decided to give it a whirl. We did three races; winning at Lime Rock, I was leading the Minnesota GP, at Brainerd, when I had engine problems—I think David Hobbs won, in the other race we retired again with engine problems. However, it was a good experience, I think we made our mark, and financially we didn’t do too badly. We returned to Europe to finish off the Guards Championship, which came down to the wire between Trevor (Taylor) and me, at Brands Hatch. We both crashed out.

Wasn’t it a backmarker, Chris Warwick-Drake in his Cooper, who took both of you out?

Gethin: I can’t really remember the fine detail of the race, I was leading the championship on points and Trevor needed to beat me by a margin to take it away from me. Had we not gone to America we would have won the championship very easily.

Was there a logistical problem in locating spares in America? In the UK everyone is no more than a couple of hours apart.

Gethin: No not at all, McLaren were big over there as they were competing in Can-Am. They had good connections over there, the engines were all made by Chevrolet so, all the bits were over there. The engines were put together by an American engine development company. No, it wasn’t a problem. All we had to do was get the car and the team to each race venue.

You mentioned the winter testing with Bruce. How did you find him as a person, and what was your relationship with him?

Gethin: Bruce was the guy who gave me my chance in Formula One, he’s the nicest person I’ve ever met in motor racing—full stop! He was a most helpful and genuine man. When he was killed, on June 2, 1970, I was there with him testing at Goodwood. From there on I think my career took a different path. I think things would have worked out better for me had he lived. He was totally behind me, he kept pushing me and I responded. Like most people who worked for him, I would have done anything he asked of me.

Photo: Pete Austin

In essence, he was your mentor?

Gethin: He was exactly that, he was a fantastic person who could motivate anyone by his presence, his niceness, and his genuine nature. He was one of those people whom you don’t meet too often in this world.

For 1970 you ran with McLaren again, but under the Sid Taylor banner?

Gethin: A McLaren, yes, but a different car. It wasn’t a particularly good car, but it gave us the Formula 5000 championship for a second year–we won it with good results early on in the season. It was the year I started in Formula One at Zandvoort, in July—if I remember rightly. I had spoken to Bruce prior to the Belgian GP at Spa; he said, “I want you in the second car with me at Spa.” Denny Hulme had been injured during practice for the Indy 500 due to methanol burns to his hands after a fire. I said to Bruce, “I can’t do that Bruce I’m down to drive the 5000 car for Sid.” Bruce replied something along the lines of, “Fuck Sid! We’ve provided you with a car to learn the ropes of Formula One, to get involved—with Can-Am too”

That was, if were needed, solid proof that you were being groomed and nurtured for greater things?

Gethin: For sure. When we did the testing of the 5000 car over the winter months at Goodwood, and remember Bruce was a brilliant test driver and development engineer, he was impressed with the fact that as he improved the car I improved my times. There’s a really good chance that my career would have turned out different had he not been killed.

Photo: Peter Collins

What was the main difference driving in Formula One from Formula 5000? In 5000 you were head and shoulders above the rest, taking the two championships, while Formula One held a new challenge with the “crème de la crème” of the world’s racing drivers? What was that environment like?

Gethin: Yes, you’ve got stiffer opposition. You’ve got two McLarens, two Ferraris, two Tyrrells, and two of something else, you’ve got the best drivers in the world of single-seaters—theoretically. I think in those days a Jimmy Clark, or a Jackie Stewart could win a race in an inferior car, just. Today I don’t think even the best of drivers would have a hope. The competition was very strong. It was also, as now, development, development, development; we made the best of the then latest technology, which looks pretty basic in the light of today. Driving a Formula One car was so different from driving a Formula 5000 car—the Formula One car was a high-revving machine with very little torque, the Formula 5000 had a great deal of torque and at some circuits was a quicker car that a Formula One car.

I think this is where you actually hold the record for beating a field of Formula One cars with a Formula 5000?

Gethin: Yes. It was the 1973 Daily Mail Race of Champions at Brands Hatch. It was a good weekend, there were two Formula 5000 races, one on Saturday—all 5000 cars, and the Sunday mixed grid of 5000s and F1 cars. I think my win can be considered as being, “by default” as two or three of the F1 cars broke down.

Peter, you’re too modest…

Gethin: … no, just truthful. The first race I did with a mixed field of F1 and 5000 cars was the 1970 International Trophy race at Silverstone. I was about 4th or 5th quickest with a good F1 field. Now Silverstone would have suited the F1 cars more than the 5000s due to the high-speed nature of the circuit. F5000 cars were better on the slower circuits due to having a greater amount of torque. I was quicker than Bruce in the F1 car—that particularly “chuffed” him; he was really proud of that and smiled all the time.

Photo: Maureen Magee

His boy was coming along nicely, his investment was paying off?

Gethin: There was a certain amount of that, but he liked to see his 5000 car beating so many of the other F1 cars.

All good things come to an end. Bruce’s death, as we’ve already mentioned, had a significant impact upon your career. What actually happened with the relationship between you and the McLaren team?

Gethin: When Bruce was killed the team was run by Phil Kerr. Phil was a director and on my side, and then Teddy Mayer, who wasn’t an unpleasant man, but wasn’t a motor racing man. As far as I’m aware he got into McLaren as he was from a very wealthy American family and very good at getting money without the need of putting his own in—but, again, he wasn’t a motor racing man at all. For 1971, Ralph Bellamy designed the new McLaren M19 with rising-rate suspension, which no one understood or knew how it worked. It worked the first time out with Denny (Hulme) at Kyalami, South Africa; I couldn’t make it work and I wasn’t a good enough engineer to work out how it worked. Denny couldn’t make it work after the South African race, so we were left with an ill-handling car that we couldn’t get to grips with. About halfway through the season, Teddy, who had every right, came to me and said, “This new car, we’re not getting anywhere with it, so for the last two races, Canada and the U.S., we’re going to put Mark Donohue into your car.” Mark Donohue was the American equivalent of Bruce. I was quite miffed at this, but I felt it was fair and could see why they would do it. I could make the car work, Denny couldn’t—but they were hardly going to replace Denny. So, I fell out with Teddy as he was telling me I was to be replaced in the car. I had been approached by Louis Stanley, of BRM, who wanted me to drive for the team in 1972. After being told I was being replaced at McLaren, I went to Louis Stanley and told him I was ready to drive for him as soon as he wanted me. I was offered my first BRM drive at the 1971 Austrian GP. So, I went to Teddy Mayer, thanked him for my time at McLaren, and told him I would leave immediately rather than wait to the end of the season. I can tell you, it did give me a certain satisfaction in doing that.

I drove for BRM at Austria, and then there was the race at Monza.

Photo: Maureen Magee

And, what a race…

Gethin: Yes, a good race. I won it fair and square on a high-speed circuit that didn’t really suit my driving style—I didn’t like high-speed circuits. What happened during the race, I was something like 10th or 12th quickest, it didn’t really matter because you could easily slipstream through the field and be up among the leaders. Anyone could win; it was a matter of dicing and seeing where you were at the finish. I came up to a slower car, I think it was Oliver in a McLaren (ha! ha! ha!), I lost the leaders. I was something like 8-10 seconds behind them. My pit crew was giving me lap times, and minus times to the tenth of a second, every lap I gained a tenth or two tenths. I was really driving really hard and the car was working really well, too. I was over revving it a bit—probably for half the race, I’d say. Eventually, I got within two and a half seconds of the leaders. I could easily get another tow. I thought to myself, “you’ve done the hard bit, you can win this.” I led the last three or four laps and I got it clear into my mind where I should be on the last lap, particularly at the Parabolica—that was in the top three places. I think Ronnie Peterson and François Cevert thought the race win was between them. When it came to braking for the last time at the last corner I was on the inside. I couldn’t stop, I put a couple of wheels on the grass I just couldn’t slow enough, I was in the lead but, sideways. I thought I could still win as long as I just floored it. And I did, by 0.01 of a second, Peterson was 2nd, Cevert 3rd, Mike Hailwood 4th, and my team mate Howden Ganley 5th—all of us within 0.60 of a second. I think they measured my win distance to about three feet! I was so determined that having caught them I was going to win it.

Your record stood for over thirty years, until a certain Michael Schumacher beat it.

Gethin: Well, they put chicanes in not too long after that. It’s strange, I went back to Monza and drove a Formula 5000 Chevron, in the 1974 Rothmans Championship, and won easily. Funnily enough, I think the circuit liked me. I took my son over there just 12 months ago, to show him this great place, they were all very good and gave me a car and the circuit to myself—it was very interesting. I love the Italians and love their country.

Winning that race meant you finally had arrived and things were looking up, did you?

Gethin: It was toward the end of the season, I led the non-championship Victory Race at Brands where my teammate Jo Siffert was killed. I was quickest in practice and equal with Siffert, I got away well I started from the middle of the front row—I was a good starter, Siffert made a bad start and ended on the grass, I think. I was leading from Fittipaldi, it was tough, but I held on—then Siffert had the problem with his car, the tire, suspension or something broke, he was killed and the race was stopped, after just 14 laps. It could have easily been my car, motor racing was dangerous in those days.

Photo: Maureen Magee

With so many accidents and deaths in that period, was the prospect of death something that played on your mind at times?

Gethin: No. No, because it was never going to happen to you. I’m sure it was the same feeling as Spitfire pilots had during the Second World War. You know it’s dangerous, but it would never happen to you. If you started thinking that way you should just get out. So, no, it was never going to happen to me.

You had a couple of races left that season?

Gethin: Yes, the Canadian GP, where my suspension broke, and the USGP where I’m not too sure what happened and I ended up a lap down in about 9th place. I can’t recall the reason, perhaps it was just I didn’t drive very well?

In 1972, BRM did a deal with Marlboro offering a lot of money for each car that was entered. The team had won two Grands Prix in 1971 Siffert had won in Austria and I at Monza, and Louis Stanley had this crazy idea that if we could run two cars or three cars, why not run five cars? Quite frankly, I just wasn’t possible to run five cars, we were trying to run five cars with a staff for just three. I think Tim Parnell, the team manager, should have told Louis it was impossible to do—although, Louis Stanley was a very strong character, indeed. Despite him being a bit pompous, he had done some good with Grand Prix racing on the medical side of things—however, he really screwed up 1972. It was a ridiculous season no one knew who would be in the team from one race to the next.

Photo: Pete Austin

The team had a good result at Monaco with Beltoise taking the win?

Gethin: That was purely down to the wet conditions, and our Firestone tires being much better than Goodyear. I remember in practice going in for new tires, but there were so many cars we didn’t have enough to go around for us all to have new tires. I put up 5th quickest time on tires that were simply shit! I was both proud of my grid place and furious about the tire situation. In the race, on about the 5th lap I was following Jackie (Stewart), it was so wet and there was oil on the circuit, too. I made a mistake on the fast chicane, I either braked late, skidded on oil, or whatever and ended up on the top of the chicane—so that ended my race. After that it was a year of very unhappy situations, everyone in the team lost confidence, and the one thing a successful driver needs is confidence. I had one instance where, and I only learned this some months after, BRM had brought in a mechanic for the weekend. He worked on my car and put the rear brake pads on the wrong way round, so there was steel against steel instead of brake pad material against steel. Out on the track I put the brakes on and nothing happened I just went straight on. I wrote the car off, I didn’t hurt myself, but that summed up my season. Louis Stanley still held me responsible for the crash, knowing full well what had happened. Tim Parnell never told me either, and he knew. Certainly all the mechanics knew, they never said anything. It was a mechanic from another team I was driving for who eventually told me. Formula One made me unhappy, although I was really happy in Formula Two and sports cars.

I decided to return to Formula 5000, why drive a third-rate Formula One car when you can drive a first-rate Formula 5000 car? The 1973 Chevron was quick straight out of the box, no testing, nothing, and I won the first two races of the first weekend. The car didn’t do too well when we went to America, it wasn’t developed properly, and we looked at what Lola had to offer.

Your final Formula One race was the 1974 British Grand Prix for Graham Hill’s Embassy team, how did you get that drive?

Gethin: I knew Graham very well, I played golf with him, and he was a mate and a lovely chap. Graham ran his own team and I had mentioned in passing that I would love to drive for him should the opportunity arise. He was running two cars in the British Grand Prix, money was tight, and the second car was to be run for Guy Edwards—who had a reputation in those days for finding money to sponsor motor racing, he probably still is. Guy was a good driver, rather than a great driver, and for some reason or other he couldn’t race, he had a problem of some sort. I got a call from Graham and he asked me to drive for him. I went along to first practice and the engine broke. Nothing to do with me particularly—these things sometimes happen. I was given the spare car, which was set up for Graham, who was some four inches taller than me. I had the seat belts incredibly loose so I had the room to move down to brake, and then lift myself up to drive. It was a disaster, a complete waste of time, so I stopped. I was somewhat frustrated, I would’ve enjoyed the drive, Brands was a favorite circuit of mine. I think I could have finished quite reasonably.

Your next Formula One experience was as a team manager at Toleman?

Gethin: Yes, I got that from my experience in looking after Beppe Gabbiani with Mike Earle. He was driving in Formula Two and was a bit of a wild man, he kept falling off. Fortunately, he listened to me and started driving a little better and results started to come his way. From there Toleman asked me if I was interested in taking the job as their team manager, which I accepted. I had two drivers to look after; one was Johnny Cecotto and the other, Ayrton Senna.

Photo: Maureen Magee

You were at the 1984 Monaco GP which was stopped due to rain, somewhat controversially?

Gethin: I was a blatant fiddle. I protested, but we were just a small team against the might of McLaren. I have no doubt they cheated. They could see they were going to get beaten and they got the flag waved earlier than it should have been. Jacky Ickx waved the flag, but he was simply acting under orders, he had nothing to do with the decision. If you think about it, it was the “jewel in the crown” race sponsored by Marlboro, with a Marlboro car in the lead. For sure, Senna would have passed Prost within a lap or two the way it was going. Pressure was put onto the organizers to stop it before he did.

Looking back, and omitting the Italian GP victory, what is a high point of your driving career?

Gethin: I have driven many races, some which people have never heard of. The Formula Two race at Pau was particularly pleasing. I was leading the race easily when I had a problem with the fuel metering unit in the engine—the engine was either full rich or full lean, no halfway point. Pau is a very tight circuit, and from this once “walk in the park” race where I was waving to people and members of the press as I went around, the last few laps were high drama trying to keep Patrick Depailler at bay—which I’m pleased to say I did. I really enjoyed most of my racing career and only stopped as I was fed up travelling and living out of a suitcase. Travelling by plane means delays and missed connections, and that wears you down after a while. My son came along and I wanted to spend time with him at home.

Conversely, what would be a particular low point?

Gethin: It was the terrible death rate, so many people, friends like Bruce were being killed—they were dark days indeed. I was in all the races when Jo Siffert, Jimmy Clark, Pedro Rodriguez, and other drivers like that were killed.

People would come up to me and ask me how to become a racing driver, what does it take? They would sometimes shudder at my response, “Do you really want to become a racing driver, if so how much? Would you kill for it?” I think you need a real intensity and passion to be successful in motor racing, you can’t be half-hearted about it. Personally, I think it was more difficult than now. Nowadays, I think you could pluck any ten or fifteen drivers and put them into the right car and they’d win—whereas, in my day, some of the drivers were just phenomenal.