Imagine driving your homebuilt special, powered by a modified production car engine, in two World Championship Grands Prix and finishing 10th in the second one. These days that would earn you a World Championship point.

As amazing as Peter de Klerk’s effort was, however, there is no legacy points-wise for the man who drove a racing car that he built himself in a tiny garage that had no electricity and the only electric tool he possessed was a ¼-inch drill!

Peter David de Klerk, “Pdk” to his friends, was born in 1935 at Pilgrim’s Rest, an old gold panning village in South Africa’s Eastern Transvaal.

After serving his apprenticeship, as a diesel mechanic, he moved to the coastal city of Durban when in his early 20s, where he got a job as a mechanic in the maintenance division of a company that operated trucks transporting goods in the busy harbor. At that time, the Natal province was the strongest racing center in Africa and the home of numerous ingenious racing “specials.”

The racing bug bit de Klerk after he watched some early racing films, and in 1958 the ambitious young man and two friends decided to go to England to learn more and seek a career in professional motor sport.

The cheapest way to travel the 6,000 miles to England with no money to speak of, was to hitchhike through Africa—knapsack on the back and a school atlas to guide them—but when “push came to shove” his friends pulled out of the venture and Peter did the trip on his own!

“I got to Bulawayo in Rhodesia all right, and after a while I reached the Belgian Congo. But they wanted a hell of a deposit at the border and I could not get into the place, so I had to retrace my steps and hitchhike all the way back to Salisbury in Rhodesia.

“At times I waited for hours for a lift, and would take a ride in anything. Rickety trucks, battered lorries and so on. Many of the roads were rough dirt tracks, and I slept anywhere I could find a shelter. On occasions that meant in the bush at the side of the road. I decided to bypass the Sudan—there was a war going on there,” he reminisced.

He then hiked to Mombasa and managed to get work as a “skivvy” on a ship that was travelling to Marseilles.

“When I got to France it rained for three days non-stop. Nobody would stop to pick me up, and I decided to walk to London. Anyway, eventually a kindly truck driver picked me up and took me all the way, and we ferried across the Channel.”

Eventually, after two and a half months of travel, an exhausted and malnourished PdK arrived in London.

“I was in poor condition and somewhat shattered, but there was a place called the Overseas Visitors Club that I went to. Imagine my surprise when I heard a familiar voice. It was a friend from Pilgrim’s Rest called Mac Wolfson, and he was working in the kitchen. So I was able to scrounge three meals a day!”

Two days later Peter had “pulled himself together” and unannounced made his way to the door of a “Mr. Chapman” in Turnpike Lane. He was seeking work. He was hired immediately because of all the people working there he was probably the only qualified mechanic!

Peter was given the job of rebuilding the Coventry Climax GP engines that were being used in the 1958 season. He worked alongside Mike Costin and Keith Duckworth and travelled to the famous races at Monza and Le Mans.

“Lotus was a tiny factory, and we worked 16 hours a day. The Climax engines had been ‘throwing rods’ with regularity. It turned out that they were not tightening the big-end bolts properly. Now, I never owned a torque wrench, but I knew how to tighten a bolt and none of the motors I built broke.

“I prepared the engines for Graham Hill’s car (Lotus 16) and the older one of Cliff Allison (Lotus 12) for the Italian Grand Prix at Monza, and they both finished well. (6th and 7th). After that Graham and Cliff took me to a restaurant for dinner in Graham’s Speedwell Austin A35—that was a special memory.

I stayed at Lotus for most of the season but I was getting nowhere so I went to work in the maintenance department of the British School of Motoring for a while. I had made a few bob so I bought a motor bike and toured Holland, Germany and Scandanavia, taking in races where possible.”

During the 1960s and 1970s, South Africa was unique in having its own Formula One Drivers Championship. It developed into a keenly contested affair, and the South African Grand Prix, from 1962, was a round of the World Championship.

After some time, de Klerk returned to South Africa and was employed by racing champion Syd van der Vyver at Blake Road Motors (known as the “BRM” people) in Durban, and began to assist in the preparation of Syd’s very speedy Cooper T43-Alfa Romeo.

On free weekends he and Pat Phillips, who had a little 500-cc Wishart-JAP, used to travel the 50 miles up to Roy Hesketh circuit, near Pietermaritzburg and flog the car around until the engine broke.

“It usually dropped a valve,” de Klerk remembered. Then they would “bring it home, effect repairs” and do the same thing the following week.

He and Pat then decided to build their own car, “I had got tired of working on other people’s cars.”

They left the peaceful coastal city of Durban and moved to Johannesburg, the “city of gold” where “the money was better.”

Peter obtained employment at Continental Cars, an Alfa Romeo dealership, owned by the Pieterse brothers, and was tasked with preparing their Lotus 15-Alfa and various exotic racing sedans.

Legend has it that during the 1960 nine-hour race at the bumpy and poorly surfaced Grand Central track, the Lotus XV damaged the diff casing after hitting a bad hump. Peter plugged the hole using a lump of tarmac and the car finished 2nd overall!

Ernest Pieterse was to win the South African Drivers Championship in 1962 with a Heron-Alfa (the neat little Les Redmond/Jim Diggory-designed Gemini-type car) and then raced the ex-Jim Clark Lotus 21-Climax with success, winning the South African Drivers Championship in 1962. Pat got a job as a machinist at Unilever.

“The Heron could really ‘go.’ It was very light and I got a few ideas from it.”

The ambitious racing car constructors found accommodation in a room at the New Market Hotel, renown for its hard drinking mining clientele, but near the Alberton workshops of Doug Serrurier, a leading light in the South African motor racing arena and the constructor of the LDS racing cars.

Importantly, they managed to rent a lock-up garage at the back of the hotel, but it had been poorly maintained. The tin roof leaked and it had no electricity. (Much like South Africa 55 years later!)

A long extension cord from their room provided lighting and power for the only electric tool they possessed—a ¼-inch drill. A workbench was made from four empty 44-gallon oil drums and a stout plank. To this they bolted a vice.

Then, in the evenings after work and on weekends they started to build their “F1” car.

Every spare penny went into the project.

“We had so little money that we even purchased cigarettes in ones and twos because a box was too expensive.”

Pat drew up the suspension and other components to ensure the wheels pointed in the right direction and the suspension geometry, it was later discovered, was very like that of a Lotus 18. This makes sense in the light of Peter’s involvement with Syd van der Vyver and his work at Lotus.

They acquired parts of an old Tiger Moth airframe to obtain the high-quality steel tubing they deemed necessary for certain duties, but other tubing used was plain ERW tubing.

“Pat was an excellent machinist. One of the best,” recalled Peter.

A dummy chassis from large diameter tubing was made to make sure that the wheels and suspension components would fit. This was similar to Cooper’s ideas at the time.

Then this chassis was scrapped and work begun on the “proper” one. This was also made from large-diameter tubing, but they then decided that this was not the way to go and they changed to smaller diameter tubing with more triangulation.

Lifelong friend Lewis Baker comments, “Peter welded the chassis himself, using at first nickel bronze utectic rods, but due to the cost thereof he used a cheaper ‘generic’ for finishing the job.”

At the outset it was decided that no open holes were to be drilled in the chassis, everything would have to bolt on, and all tubes would be sealed.

The tubes were flushed with oil before final nickel bronze welding to ensure no corrosion.

Wheels, uprights, steering rack and brakes were sourced from the Cooper factory by Doug Serrurier, who was well known to the Cooper family.

Urban legend suggests that Doug Serrurier helped with the construction of the Alfa Special, but although PdK and Doug were good friends, Doug had no part in the building of this car.

The gears were made locally by Lasch Cranes, a factory in Germiston near Johannesburg, and a Citroën Light 15 gearbox was bought from a scrapyard.

The engine started life as a stock standard Alfa Veloce 1290-cc of the 101 series.

PdK then set about modifying it. (Contrary to belief of some, these “South African” race engines were modified locally and not by Conrero of Italy.)

The engine ran a standard crankshaft, Veloce rods, 79-mm Mondial pistons, modified Maserati Birdcage valves and various cams during development.

The big valves would not fit in the combustion chambers as they fouled the centrally located 14-mm plug, so the old plug hole was welded up and a 10-mm offset plug hole was drilled and tapped.

The beautiful body was made by an elderly Italian craftsman, Mr. Brega, and after more than two years of painstaking effort the car was finished in early 1962.

At its first practice session at Kyalami, Pat slid off on the uphill right-hander Leeukop and demolished the left front corner of the car.

While the original idea was for Peter and Pat to alternate driving, Pat never drove it again! The chassis would continue to bear the scars of the repair.

The car made its race debut on March 17, 1962, at Kyalami. It was immaculately prepared and looked great, and—importantly —it went as good as it looked. Peter qualified 3rd-fastest for the Rand Autumn Trophy at a respectable 1 minute, 43.0 seconds. Sam Tingle’s LDS-Alfa was given pole position with a very dubious 1 minute, 40.8 seconds, ahead of Ernest Pieterse (Lotus 21-Climax) at 1 minute, 42 seconds.

The car and driver combination was immediately competitive. Against the established front runners de Klerk drove a confident and sensible race and finished 4th. Interestingly, over the 48 laps (two heats of 24 laps) Peter’s aggregate time was only half a minute behind the winner John Love (ex-works Cooper T55-Climax) and he was only one second behind 3rd-placed Sam Tingle.

A string of podiums in events at East London, Kyalami and Roy Hesketh followed before the remarkable car won the Coupe Gouvernador Generale at Lourenco Marques only four months after its race debut.

These strong performances resulted in de Klerk finishing 4th in the drivers championship although he had missed the first few rounds. Despite this, however, he was not accepted as an entry in the 1962 South African Grand Prix at East London where Jim Clark and Graham Hill would fight it out in the title decider.

Undaunted, he scored a narrow win in the Daily Dispatch Trophy race, a curtain-raiser for F1 cars before the Grand Prix (the paying public certainly got its money’s worth in those days), after a race-long duel with Bob van Niekerk in a brand-new Lotus 22 with 1500 Ford power. Interestingly, their lap times were faster than the qualifying times of six of the cars in the actual Grand Prix!

Italian businessman Jack Nucci was a prominent enthusiast and a “patron” who ran Italian cars such as a Maserati 200SI and, recognizing Peter’s ability, he purchased Pat’s share of the car and began to provide assistance in the racing effort.

Peter recalls, “Jack did not pour money into the project. He said that he would not sponsor a dead fish. He waited to see how we would go first.”

The 1963 season was dominated by the classy Neville Lederle in his superbly maintained Lotus 21, but de Klerk was 3rd in the championship. Amazingly, at times the home-built car was able to match the speeds of the Coventry Climax-powered cars of Lederle and John Love’s ex-works Cooper T55.

For the record, Peter won the Rand Winter Trophy at Kyalami early in the season, and the Alfa Special was also victorious in two non-championship events—the Dickie Dale Memorial Trophy at Pietermaritzburg and Coupe Gouvernador Generale at Lourenco Marques.

The Rand Grand Prix at Kyalami on December 14, 1963, was perhaps the Alfa Special’s finest hour—or 82 minutes to be more precise.

The race was an eagerly awaited showdown between the Lotus 25s of Jim Clark and Trevor Taylor and the Ferrari duo of John Surtees and Lorenzo Bandini in the Dino 156s, Surtees driving an “aero” version and Bandini the “spaceframer.”

The race was run over two heats of 25 laps each as the organizers catered for the crowd’s desire to see two starts and, should cars have mechanical trouble in the first heat, there was a good chance that they could be repaired for the second heat. Race day was unbelievably hot, even for the locals who lived at the high altitude of the Highveld, and the temperatures played havoc with engine cooling and fuel pumps.

Team Lotus struggled with fuel vaporization, and some teams attempted to cool their fuel pumps by packing dry ice around them. For the first heat Surtees took pole position with some ease and Taylor narrowly pipped Bandini, while 5th on the grid was de Klerk’s “special”—fastest of the four-cylinder brigade.

As the Ferraris stroked away to a comfortable 1-2 in the first race, Clark and Taylor struggled with poor engine performance and were harried by de Klerk and Love. When the Lotus pair stopped, de Klerk and Love ended the race 3rd and 4th after a closely fought duel of their own.

With grid positions for Heat Two decided by the finishing order in Heat One, de Klerk shared the front row with the works Ferraris and, to the delight of the patriotic home crowd, out-dragged the scarlet cars from the getaway. His lead was brief, however, and by Crowthorne Corner the cars from Maranello were ahead. While Surtees raced off to another easy win, Peter fought tooth and nail with John Love’s Cooper as they both took turns harrying Bandini.

Meanwhile, the Lotus pair was performing better than in the first heat, their mechanics having fitted extra air scoops during the recess, but although both cars were down on power the V8s crept up on the duel for 2nd position. Late in the race, de Klerk missed a gear and Love and Clark sped ahead of him, but Peter was undaunted and stuck to the tail of the Lotus 21 and with two laps to go a huge roar from the crowd signalled that he had overtaken Clark and was gaining on Love.

The Alfa Special eventually finished 4th in this heat, less than two seconds behind Love’s Cooper and some six seconds behind Bandini. On aggregate times de Klerk was 3rd in the Grand Prix.

After the race an amazed Colin Chapman walked to the Nucci pits and said, “de Klerk you should take this car and race it in Europe. It must be the fastest 4-cylinder car in the world.”

Two weeks later, in the World Championship Grand Prix at East London, PdK qualified 16th on the grid but, plagued by gearbox troubles that caused his retirement after 53 of the 85 laps, he was never able to compete with the faster 4-cylinder cars.

Sadly, the march of technology is not kind to underfunded private drivers, and although Peter improved his car for 1964 and was locked in close combat with John Love (Cooper T55) for the season and took 2nd place in the Drivers Championship—winning three races against Love’s four—by the time the World Championship Grand Prix arrived on January 1, 1965, the old 4-cylinder production car engine car was hopelessly outclassed by the factory teams.

Additionally, a tire war was developing, and tire widths had increased enormously. Goodyear had provided some of the runners with the new “doughnuts” whereas Dunlop supplied its “tried and proven” rubber to most of the field.

In terms of development, the Alfa Special was much faster than the previous year, qualifying easily, and bettering its grid time by nearly 2.5 seconds. It was also faster than the new Brabham BT10s of visiting drivers Paul Hawkins and David Prophet.

Jim Clark’s V8-powered Lotus 33 dominated the race, winning comfortably from the Ferrari 158 of John Surtees, but Peter drove a steady race to bring his car home in 10th position with the Willment Brabham of Paul Hawkins the only 4-cylinder car ahead of him. This event was the last ever 1500-cc Formula One race held in South Africa, and the three-liter formula was subsequently adopted, a year ahead of the rest of the world.

Impressed with the achievements of his young charge, Jack Nucci imported a 2.5-liter Tasman Brabham BT11-Climax. The Alfa Special passed on to Leo Dave, and competed in the Gold Star category for cars up to 1600-cc into the 1968 season.

With the Brabham’s Climax engine stretched to the popular 2.7 liters, de Klerk enjoyed several successes and was runner-up in the South African Championship. Peter went on to drive other Formula One machines such as Brabham BT20s, BT26s and a Lotus 49 that had been passed down by Dave Charlton when he acquired a Lotus 72.

“The Lotus 49 was the best car I ever drove, but I lost the drive after a falling-out with the team’s director,” he says. Some sources contend, however, that he was driving it “embarrassingly” quickly. Nonetheless, Peter scored two runner-up spots to Dave Charlton’s Lotus 72.

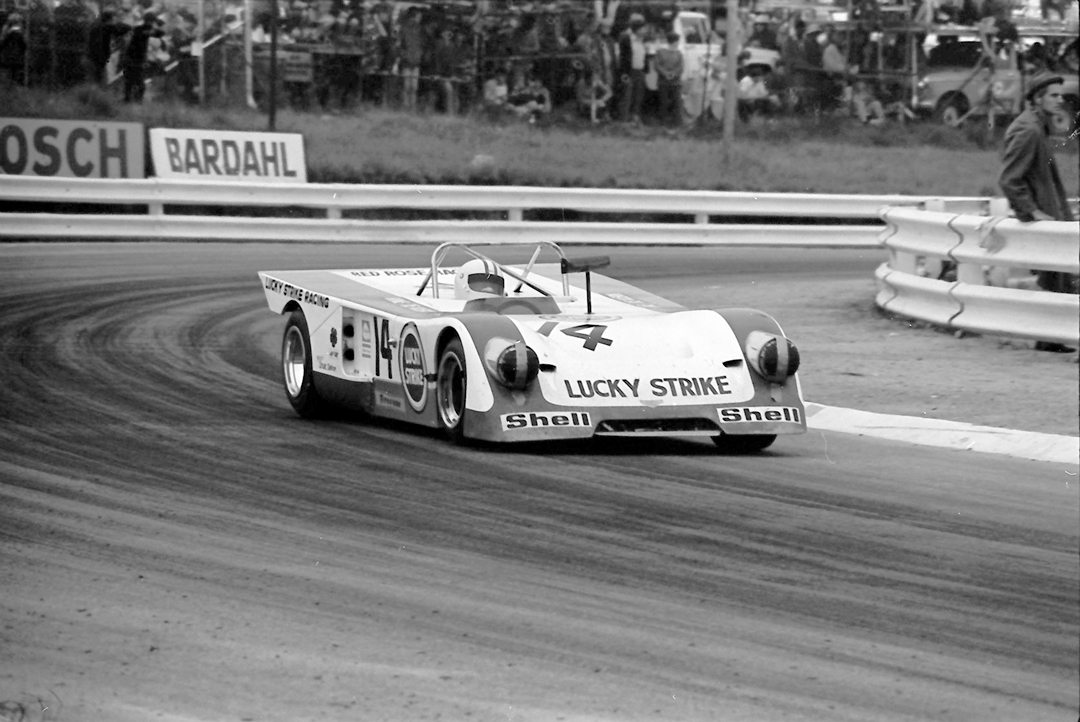

When the SA championship moved to accommodate F2 cars in 1973, de Klerk finished out his single-seater career having occasional drives in the “spare” Team Gunston Chevron B25 F2 car alongside John Love and Ian Scheckter.

“Mixed with pukka F1 cars and F5000s we had little chance though.” Nonetheless he was first F2 car home in the Bulawayo 100, and also achieved a couple of 2nd places in class.

A talented and versatile driver, PdK was also much in demand for his mechanical skills and had a successful career in sportscar racing, not only in Europe where he raced the Nürburgring 1000, two BOAC 500s and outings at Spa and Le Mans during 1966 and 1967 in cars varying from Ford GT40s to Lola T70s to Ferrari 250LMs.

It was a busy time, for he was commuting between South Africa, where he was contesting the F1 championship in Jack Nucci’s Brabham BT11, and racing sportscars in Europe.

“I had become a sort of professional driver,” he recalls.

“I had co-driven with Mike d’Udy in a number of South African endurance races in his Porsches, and in 1966 I was supposed to co-drive his Porsche 906 in the Targa Florio and was really looking forward to the experience, but unfortunately Mike crashed the car on the first lap.”

However, a month later, driving with Udo Schutz he finished 6th at Le Mans with the Langhek Porsche 906 after Jo Bonnier arranged him a works drive.

“It was a superb engine. Titanium rods et al. It ran beautifully. Then I made a big mistake. I decided to come home instead of taking an offer from Huschke von Hanstein to drive in the Posche team,” he recalled.

He was involved with John Surtees in the disastrous Lola-Aston Martin Le Mans project in 1967, but his co-drive with Chris Irwin ended after only 25 laps.

“That five-liter engine was absolutely no good. It was a prototype engine and not developed. Just one look at the cam lobes told you the thing would never perform. They were too pointy. Then there was trouble with the cylinder head gaskets. Another one of the causes of the trouble was crankshaft damper problems. The Surtees car only lasted about three laps and we did not do much better!”

Denzil Schultz, who was working as a mechanic at the race, recalled that during practice the Lolas had quite an appetite for devouring the Aston engines, and the team did not even have a block and tackle to remove and install the engines. “Peter was trying to sort out engine troubles that baffled the factory mechanics. There was a specific way of setting up the copper rings to seal the head, and he was the only one who knew about it.”

There were other disappointments. In 1967, he was given an opportunity to test the fabulous Mirage Mk. 1 for JW Automotive in the Brands Hatch Six Hours, with Pedro Rodriguez and the American Dick Thompson.

“I was at Brands Hatch watching the practice and Peter got the Mirage quite ‘sideways’ through Clearways and sort of half-spun but he did not stall it. Well that was the end of it. I think John Wyer said it was ‘not good enough.’ Ironically, Dick crashed the car in the race,” remembers his lifelong friend Lewis Baker.

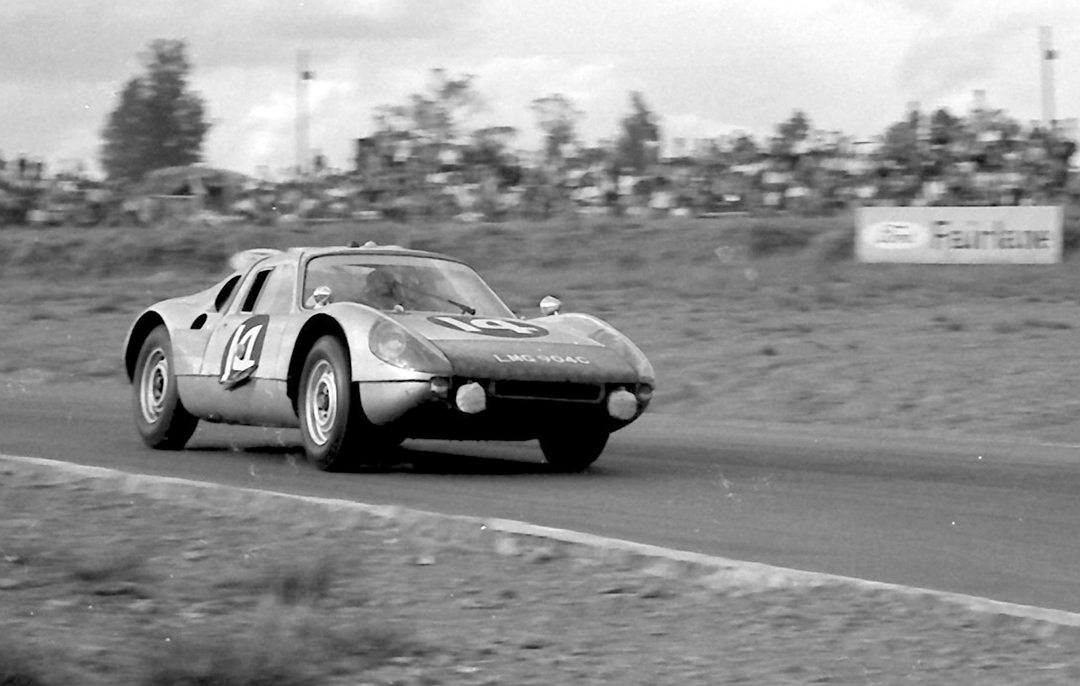

In the South African year-end Springbok Series events de Klerk scored several podiums driving alongside the likes of John Love in David Piper’s Ferrari GTO, sharing Mike d’Udy’s Porsche 904 and Ford GT40s of David Prophet. A notable win came in the 1972 Six Hour race at Pietermaritzburg when he co-drove John Abraham’s yellow Chevron B19 during the Easter weekend.

De Klerk had many interests apart from racing and enjoyed scuba diving and flying.

After stopping the motor racing he restored an old “fabric” Stinson aircraft and enjoyed many hours of flying until an accident caused by the carburetors icing up.

No doubt Peter’s modesty and quiet personality proved a hindrance to him, but he was much admired in the international racing fraternity.

While Peter later drove many famous cars and rubbed shoulders with racing’s elite, he is best remembered for the simply named Alfa Special.

One wonders if any other home-built car has ever been so successful, especially one constructed with such rudimentary equipment in such a humble shed.

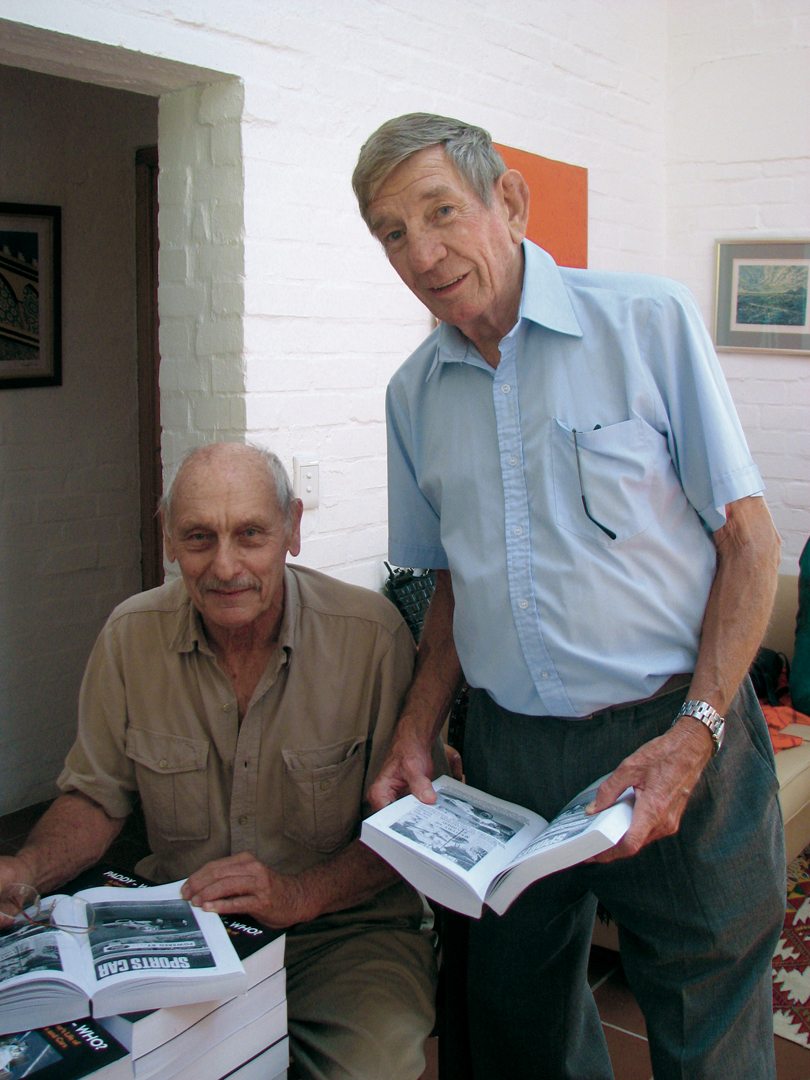

Peter de Klerk passed away, aged 80, in Johannesburg on July 11, 2015, after a long illness.