Motor sport anniversaries and centenaries seem to have filled the calendar in the last few years, and as our sport continues to get older, there will be many more. 50 Years of Lister Jaguar to 60 Years of Lotus, everyone gets a celebration or at least a tribute these days. The 50th anniversary of the fatal accident to Mike Hawthorn was marked just recently with a parade of relevant cars and people.

The Shelsley Walsh Hillclimb in the slightly remote part of the county of Worcestershire in England was the site of a rather remarkable gathering in August 2008. The Midland Automobile Club runs events at Shelsley and has done so for many decades. Shelsley is not very far from the town of Kidderminster where Peter Collins was born and raised and where his family played a significant part in the community’s life and business. Peter’s parents, Pat and Elaine, were themselves regular rally competitors before the war, and Peter did his first competition event with his father in a local rally when he was still only 15. Pat Collins wanted to race himself but didn’t manage to find time to do it, so was the first and primary supporter of his son’s ambition to be a racing driver. In 1949, Pat Collins bought a Cooper-JAP 500-cc F3 car for his son. The first several weeks of ownership were spent not only sorting the car, but learning to drive it. Peter Collins was just 17 and had no competition driving experience. Such was the family support that both his father and his mother drove the Cooper on a local airfield before it was entered for any events.

A very busy season was undertaken with the Cooper—13 events in all—and the first win came at the 5th of these events, which was, in fact, the most difficult of the whole season. Collins won the 100 Mile race at Silverstone. He had already bought a new Cooper and had the latest Manx Norton engine installed. He beat veteran Don Parker over 44 laps of the Silverstone circuit, and immediately established himself as a front runner in the formula that was to be the breeding ground for virtually all the up and coming British drivers. At the time it could truly have been said that he was very much a beginner.

Sir Stirling Moss was another of the drivers who started and starred in 500s: “I suppose one of the things that many people may not know is that we were friends for a very long time. He started very early like I had, and I remember meeting him as a ‘boy from Kidderminster,’ as I think someone introduced him to me as. In those days we seemed to have more time to meet people and, of course, we were driving in a different environment. We were doing a lot of hillclimbs in those early days, and that’s when I got to know him really well. Back in that early period, I was racing against a certain group of people all the time, and from 1949 when Peter started he was one of those who came along who I got to know. It was clear to me that he was one of the good ones.”

The penultimate event of that debut year was indeed at Shelsley Walsh, and the 500 cars were to run in a group for up to 750-cc. It wasn’t so much Collins’ performance that earned him many fans, especially among the locals, but rather the clear indication that he was very serious about what he was doing. The Collins’ JAP engine had been replaced by the more competitive Norton in the Cooper, but for this event, in order to do well against more powerful opposition, the older V-twin JAP was enlarged to 700-cc and stuck back into the car. However, the JAP blew up so the Norton had to go back in yet again. A 750 Austin and Joe Fry’s Parsenn beat Collins into 3rd his first time at Shelsley. However, Peter and his father Pat and their band of supporters got very good at building engines and fitting them at almost a moment’s notice. Over the first three years of his career, Collins did some 64 events in either a Cooper or J.B.S. F3 car that had been created primarily to use 500-cc engines. However, Collins had 500, 700, 750, and 1200-cc units ready to go into his car to maximize his chances of winning.

Moss also pointed out that part of being a serious competitor in those days was spending a lot of time at hillclimbs and sprints, honing one’s skills in driving on very narrow roads with lots of things to hit on either side. It also taught the drivers of the time to get the very most out of themselves and their machines from the drop of the flag. Collins, like Moss, became very good at going quickly from the moment an event started, as well as being amazingly fast on road circuits. Moss admits that Collins’ ability on road circuits, as well as the fact that they were close friends, was the deciding factor in him asking Mercedes Benz to have Collins as his partner in the 1955 Targa Florio; which they won.

Collins Nostalgia

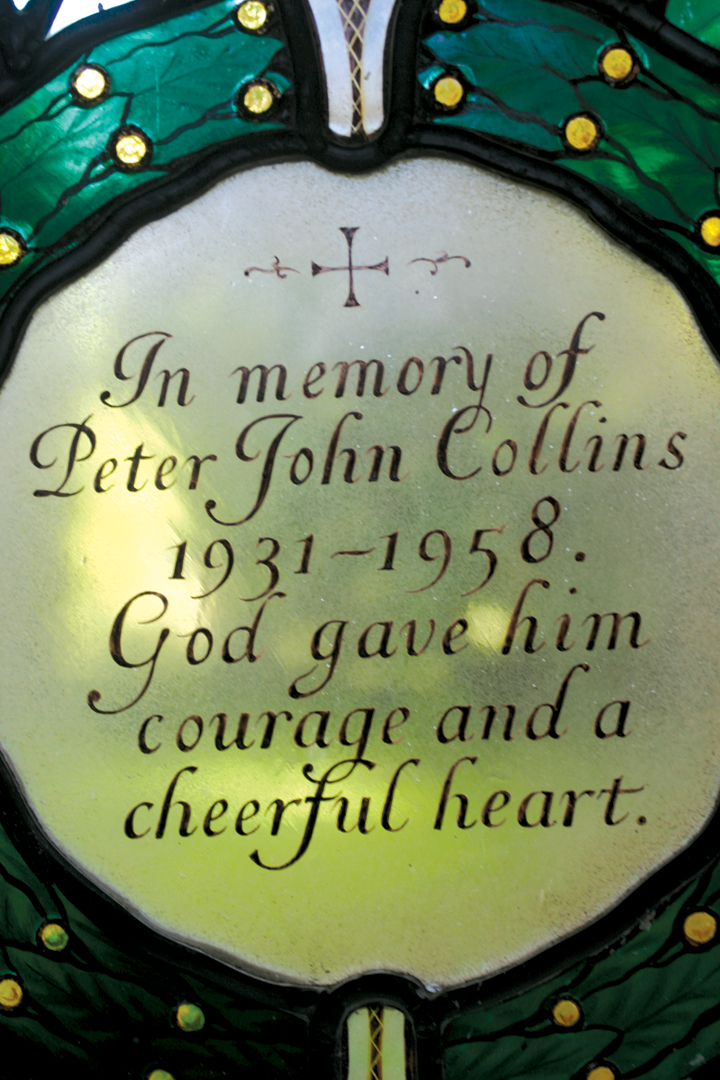

That 2008 gathering at Shelsley Walsh brought a number of things to the fore about Peter Collins. The event was staged as a tribute to mark the 50th anniversary of Peter’s death at the Nürburgring. Much to many peoples’ surprise, and to some extent to her own, Louise Collins allowed surviving Collins family members to talk her into making the trip from Florida as the guest of honor. Her presence brought history out of the woodwork and we were treated to a weekend of non-stop Peter Collins tales. The proximity to his family home lured many old contacts who never go to motor sport events. There was the ex-boyhood friend who came carrying his invitation to the post-wedding party hosted by Louise and Peter in 1957; the son of Pat Collins’ solicitor, with a few tales to tell; a man who lived his own boyhood in Shatterford Grange, the Collins family home, after the Collinses had all left; several women who were school friends and “admirers!” of Peter; former neighbors who felt he had put Kidderminster on the map for more than being just a carpet-producing town; and Peter’s brother in-law with his daughters. They had not heard some of the tales their mother and the uncle they never met got up to!

What those of us present at that meeting heard many times was the fact that “Peter Collins was just a regular guy.” He was at home from international races when his career got moving, and he stood his round at the local pub, usually the Black Boy Hotel at Bewdley, which is still there, largely unchanged, though with little indication that a famous racing driver was once a regular.

There were many locals who remembered the young boy who was always present at his father’s garage business, before he had a driving license, moving trucks and other vehicles around the yard. Though he had been sent off to boarding school, he quickly found ways to get back home, and after a short time converted to being a “day boy,” much preferring to be at home. The business must have been the attraction because his relationship with his father was strained at times. Peter also had a strong network of friends, some of whom he went to school and parties with, and many of them followed his career and continued the partying when he was home.

Photo: Chris Bayley

School friend Sue Palethorpe on Peter: “I knew Peter from about the time we were 14. He was then just what I would call one of our gang and as a boy was lots of fun, a great chap.” Sue said that when she was old enough she went to work for driver/team owner Bob Gerard and that helped keep her in touch with Peter. “Even when I was older, I would see Peter and his sister Tricia, and they would come to us at Christmas. We were a group of friends who just stayed in touch with each other, and he was just one of us.”

A developing professional career

Stirling Moss said that Peter was serious about being a professional driver right from the beginning. He took his racing very seriously, and the cars were well looked after. Peter’s willingness to “sort of” work in an apprentice capacity in the family business after he left school ensured that his father would continue to support his ambitions. The Cooper was used exclusively through 1950, and in 1951 there was the occasional rally and a chance drive in a Dyna-Panhard at Silverstone. Then an Allard with a Cadillac engine was added to the stable to provide the opportunity to expand into sports car racing. This beast was never very successful, but it provided the chance for Peter to practice on a much bigger machine.

While a Cooper was retained, Peter’s father bought a JBS F3 car, and Peter had eight wins in that car, while using the Cooper with 1200-cc engine to take several more victories in hillclimbs.

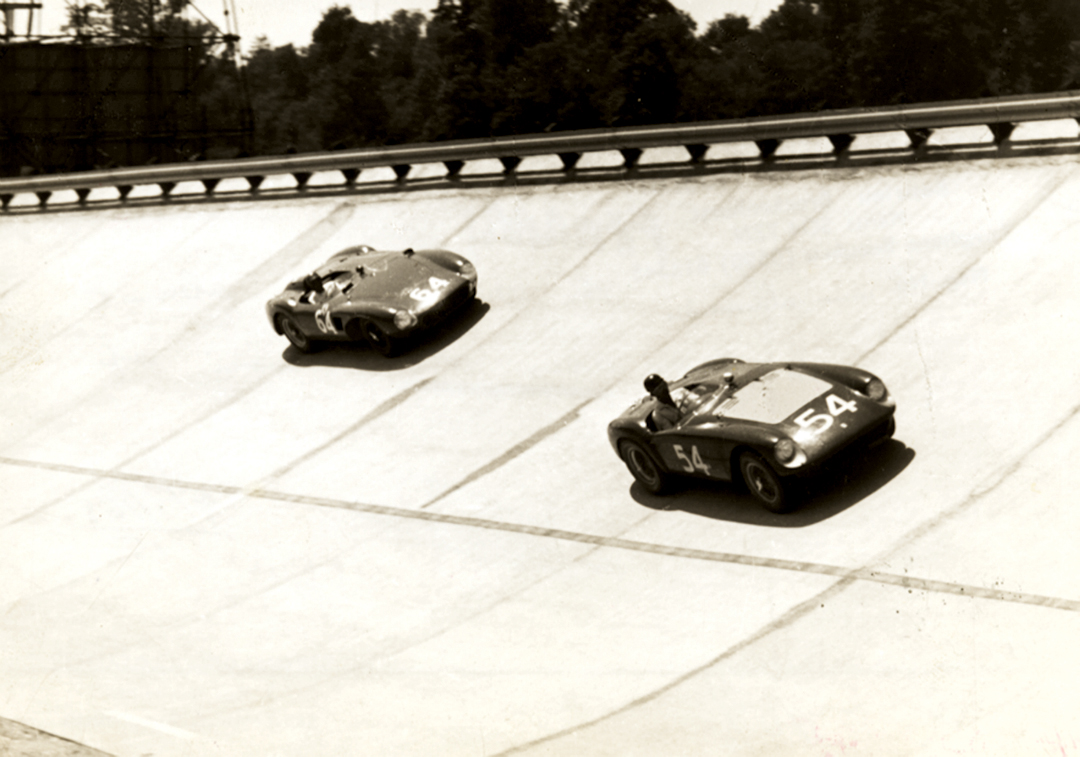

Photo: Fodisch

All the effort in 1951 paid dividends and Peter was one of the people seen to be in the running for a drive with HWM. John Heath’s company had done well in 1951 with the HWM-Alta on a low budget, but it had been announced that the 1952 World Championship would be run for Formula 2 cars. This was a great opportunity for a small company to get into Grand Prix racing, and in mid-March it was announced that Peter Collins and Lance Macklin would be the regular HWM drivers. A third car would run occasionally for Frenchman Yves Giraud-Cabantous, and Moss might also occasionally appear.

About this time a certain Mike Hawthorn had moved from racing rather “clubby” sports cars to a Cooper-Bristol, and on April 14 he won an F2 race at Goodwood. Hawthorn was always good at maximizing his publicity, and he made the most of his achievements to become well known, almost out of proportion to his actual performances. Later, particularly after they were both dead, the names of Hawthorn and Collins became inextricably linked, but they got to where they were in 1952 by very different routes, and didn’t know each other. They did later, but that was some four years later, and they certainly were never the lifelong friends some accounts imply.

On that same day in April, Peter Collins, aged still 20, was making his Grand Prix debut at Pau in southwest France, driving for a genuine though not very rich Grand Prix team. Collins found himself in the rather illustrious company of Alberto Ascari, Luigi Villoresi and Toulo de Graffenried. He was in 14th in the early laps, then moved up to 9th, then 8th before a brake problem and broken axle sidelined him on lap 43, seven laps before the end. It had been a notable start.

Onward and upward

Photo: Ed McDonough Collection

It would be fair to say that 1952 was not a dream season, at least in terms of results. The HWM and indeed everyone else, were running against a very strong and well-financed Ferrari works effort. Ascari was virtually unbeatable that year and won his first World Championship. However, Peter Collins was learning his trade. The HWM-Alta was thoroughly outclassed and outpowered. Thus Collins had to drive very hard for everything he achieved. By the end of the year he would record a 4th at Montlhéry shared with Macklin, a 6th in the French Grand Prix, a second at Sables d’Olonne non-championship race, and a 4th at the La Baule Grand Prix.

However, and more importantly, he had done other things as well. He did his last 500-cc race at Luxembourg where he was 3rd, but most significant, he had gotten himself into the Aston Martin sports car team.

Photo: LAT

Though history has John Wyer, Aston Martin’s competitions boss, inviting Peter onto the team, there seems a strong possibility that Peter harassed Wyer at every possible moment until Mrs. Wyer, Tottie, simply said “Oh John, give the boy a try!”

So Collins came on board for Monaco in 1952, the year in which the Grand Prix was held for sports cars. He had had two test sessions earlier in the year and lined himself up on the fifth row in the DB3, next to Marzotto’s Ferrari. Collins had never been to Monaco before, so he was taking things fairly easy. Both his and teammate Reg Parnell’s Astons made pit stops with overheating. Later in the race Parnell’s car stopped and he was pushing it out of the way when there was an almighty pileup with five cars in a heap, including Moss’ C-Type Jaguar, though he managed to get away. Collins avoided the mess and eventually got the only Aston to the finish in 7th.

He would drive for Aston Martin twice more that season, the next time only two weeks after Monaco at the Le Mans 24 Hours. Collins was certainly piling up the milestones: 1st Grand Prix; 1st time at Monaco; 1st time at Le Mans; would he manage a big win? There might have been a touch of regret after Monaco, as the HWM team had gone to Chimay in Belgium for a non-championship race and Peter’s car was lent to Paul Frere, who won!

Astons took three DB3s to Le Mans for Parnell/Thompson, Collins and HWM teammate Macklin, and Dennis Poore and HWM co-owner George Abecassis, plus two private DB2s. After five hours of the race, the Collins/Macklin car was the only surviving works car, and was in the top ten. At the halfway point, Collins had gotten up to 4th with steady driving. It was holding 3rd in the 20th hour when the rear axle went—as it had in Parnell’s car—and they were out, but it was a very impressive first Le Mans drive for Collins.

Photo: Ed McDonough Collection

Peter Collins was by then living in France, at least part of the time, working for the Paris Aston Martin dealer. As was fairly regular amongst British young men at the time, many were not overly keen to spend 2 or 3 of their early years doing national service, the Army. A great fuss was made over Mike Hawthorn, who had a bigger public profile than Collins, and the press view of Hawthorn was as a “draft dodger.” The reality was that Hawthorn’s physical condition, especially his kidneys, would have kept him out anyway, but he kept that very quiet in order to retain his racing license. Collins had a lower profile, and used his apprentice status and then his role as an “overseas sales person for a UK product” to protect him from the draft. Indeed, he was making his name as a professional driver and didn’t want that interrupted.

Later in the season, Collins was back in the Aston for the Goodwood Nine Hours. He was sharing with Pat Griffiths, and this pair had the DB3 in the top six in the early stages. As the favored C-Types began to encounter problems, they eased the heavier Aston further up the order. At halfway, they were in 3rd, and when Moss went in for repairs, the Salvadori/Baird Ferrari led the Aston. Then Roy Salvadori had the Ferrari battery fail and Collins moved into the lead, and they went on to a very convincing win. This made Collins the fair-haired boy at Aston Martin and secured his place in the team.

In 1953, the HWM was even less competitive than the previous year, and a 3rd at the Eifel GP at the Nürburgring was Collins’ best result. The HWM-Alta just couldn’t match the Ferrari anywhere, but neither could anyone else. Peter did seven races for Aston Martin, this time coming 2nd at the Goodwood Nine Hours, but winning at the Tourist Trophy at Dundrod in Northern Ireland with Pat Griffiths. This was a very dangerous but challenging road circuit, and again Collins demonstrated that he was among the very best racing on public roads, nearly as good as Moss, and possibly a bit better than Fangio, no mean achievement.

Photo: NMM

He had also secured a drive with Rootes which was making another major assault on the Rally des Alpes, the Alpine Rally. He was driving one of the Sunbeam Alpines, with Moss and American John Fitch also in the team. The 2000-mile route was very difficult, but the racing drivers did very well. Moss won a coveted Coupe des Alpes for receiving no penalties. Collins was teamed with Ronnie Adams, who later claimed he was expecting to do some of the driving. When Collins refused, Adams walked out and Collins recruited the retired co-driver David Humphrey, but they eventually lost all gears and had to quit. They would have been disqualified anyway. This was one of the occasions when Peter lost his rather severe temper. It didn’t happen often. Geoff Duke had felt it that year at Sebring when he hit a marker barrel and another car in the car he was sharing with Collins while they were leading.

The 1954 and 1955 seasons were odd in a sense. Collins was recruited by British industrialist Tony Vandervell into his team that was starting the build program for the Vanwall. Collins drove Vandervell’s Ferrari 4.5 Thin Wall Special in Formula Libre races, winning a few, and also did some of the early races with the new Vanwall. He also managed a few wins for Aston Martin in rather minor races. In 1955 he did a dozen races for Aston Martin, and decamped from Vandervell to Raymond Mays at BRM. He had some superb wins in the legendary BRM V-16, and drove the BRM-owned Maserati 250F in Grand Prix races, winning the Silverstone International Trophy. He made a promising debut with the new BRM P25 at the Oulton Park Gold Cup, but it retired.

The final race of the season was the magical Targa Florio in Sicily. Mercedes, which had won the Mille Miglia with Moss, wanted to win the Targa so Moss got Collins as his co-driver. They simply dominated the event, and though the car came back with many dents, they won. This was what really brought Peter Collins to the attention of Enzo Ferrari.

The Ferrari years

Before the 1956 season, Enzo Ferrari was planning his strategy. He thought that Peter Collins might be going to Maserati. He didn’t want Fangio, Moss or Collins at Maserati. Well, he had Fangio and he decided to have Collins as well, even though he would have to agree to let Collins fulfill his sports car commitments at Aston Martin. It would probably be fair to say that Collins would have rather gone directly to Ferrari for sports cars and Grand Prix, but that wasn’t on.

Collins’ early season performances were promising, but without results. Then when Aston didn’t do the Giro d’Sicily, Collins drove a Ferrari 857S with photographer Louis Klemantaski beside him and won. Then he managed a 3rd in the Syracuse Grand Prix in one of the Lancia D-50s Ferrari had taken over after the demise of Lancia in racing. At the Monaco Grand Prix came the famous episode in which Collins handed his D-50 over to Fangio and they shared 2nd place. That earned him great respect everywhere for his sportsmanship, but the author has always felt that his deference to Fangio and his rather father/son-like relationship with Enzo Ferrari tended to reflect his ambivalence towards his own father. He respected him and always wanted to please him, but they could rarely get along with each other. He could be very much the young boy in the company of these older men.

Then came the great Grand Prix win at Spa for Collins in June. There was rain in the early stages so the field was pounding round on a damp track. Collins held station behind teammate Castellotti for a time as Fangio and Moss led the way. Collins then passed Castellotti and closed on Moss at the rate of two seconds a lap. When Moss retired, he started closing on Fangio, setting a new lap record. Then Fangio also stopped and Collins flashed past and took his most important win.

Photo: Louise King Collection

A few weeks later, he won the Supercortemaggiore sports car race, teamed with Mike Hawthorn for the first time. Hawthorn and Collins were later nicknamed the mon ami mate duo after a British cartoon, and later biographies at least implied Collins and Hawthorn had always been close friends, almost that they were joined at the hip. This was not true. They didn’t spend much time together until 1957 when they were both regulars in the Ferrari lineup. While they got on in a sort of boyish way, Hawthorn was the dominant character with Collins happy to follow on alongside, if not behind. The pair began to get a lot of press, which exaggerated the relationship. This tended to ignore Collins’ own personality and interests, and his somewhat more introspective nature seemed to add to this.

Collins also won the French Grand Prix in 1956, so it had been a very successful season, but 1957 was not nearly so good. He had a few non-championship wins and won the Venezuelan sports car race with Phil Hill. Having departed from Aston Martin midway through 1956 so after the ’56 Le Mans race, he never drove for anyone other than Ferrari.

He had been introduced to Louise King, who had been visiting the Monaco Grand Prix in 1956, but didn’t remember that when they met again in Florida before Sebring in 1957. Within a few days he asked her to marry him, and very shortly after that, she did! She rarely left his side for the next year and a half.

Collins seemed revitalized for 1958. Though he had a driveshaft break on the new 156 Dino during the opening GP in Argentina, he and Phil Hill had a good win a week later in the Buenos Aires 1000 Kilometers with the Testa Rossa. They then won again at Sebring in the same car, and at Goodwood Collins took the sports Dino 206S to 2nd. He drove the 246 Dino for the first time at the Silverstone International Trophy and won. He was clearly on form and looked to be in contention for the World Championship. He and Hawthorn shared 2nd place in the Nürburgring 1000 Kilometers, after coming 4th with Hill in the Targa, and 3rd at the Monaco Grand Prix.

It all ended tragically in Germany two weeks later. The race at the front of the German Grand Prix was between Tony Brooks in the Vanwall, and Hawthorn and himself in the two 246 Ferraris. Out near Pflanzgarten, Brooks was leading with Hawthorn behind. The year before, Hawthorn and Collins had been lackadaisical and allowed Fangio to catch and beat them. I think Collins remembered this, and put his foot down in order to keep Brooks and Hawthorn from getting away. He lost control, hit the bank, and his head struck a small tree. He was dead when Louise arrived at the hospital.

Hawthorn went on to win the Championship, then died in a road crash. Collins had been talking about retiring and either taking over the family garage business or starting a Ferrari dealership. Aston Martin would have liked him in the new Grand Prix car, but he had also been talking to Cooper, and it seems likely he would have gone to Cooper in 1959. If that had occurred, what would have happened to Jack Brabham? There’s a thought!

Whatever happened, Peter Collins is well remembered, especially amongst old friends in Kidderminster, and whenever good racing takes place at Shelsley Walsh.