Tech—IT’S OK!

by Bob Williams, Chief of Tech & Safety Inspections, Sportscar Vintage Racing Association

For some race entrants, technical inspection is a moment of worry, for others, a social moment to share and exchange prep ideas, discuss specific rules compliance, and carry out the inspection. Some entrants consider Tech a bore, others a necessary evil to be fulfilled before being allowed to enter onto the speedway. For all, it is the last time official eyes will scrutinize the racecar for its readiness to run through the red mist of open competition.

Entrants need to understand that Tech inspection isn’t just about one entrant’s car: it’s about the complete field of cars being able to compete together safely! You don’t want to run over someone else’s tail pipe with your safe car, or, how about a complete roll bar?

Speaking of roll bars…one competitor brought the car to Tech with the roll bar zip tied in. He had gone to the extent of machining dummy nuts and bolts so it looked bolted in, but wasn’t. The explanation: “I don’t intend on having an accident. Besides, my car is too valuable to drill the frame for roll bar mounting.”

He didn’t understand the extreme safety compromise his solution would impose upon a fellow competitor, or himself.

Roll bars also need head-impact-area padding and an adequate headrest. Many entrants take the outlook that little or no padding is enough.

The following is really a ramble of the most often found and obvious problems encountered within the Tech experience.

Attitude: “It’s OK! I don’t plan on having an accident!”

If you carry an attitude to Tech, the inspection will only take longer as you explain to the Tech inspector that your car is perfect because you don’t intend to have an accident. Here’s a common-sense rule all racers need to remember and understand. “No one plans on having an accident. That’s why they’re called ACCIDENTS!” Fast, slow, parked, or burning to the ground, it’s always an accident and often someone else’s fault. Take the attitude that good racecar prep and rule compliance will at least help you and your prized racecar race again. Tech is about common-sense survival for entrant and racecar.

Here are some easy-to-look-for’s that occur at many events, often with the response, “It’s always been this way!” It is not a defense to say the problem isn’t a problem.

Let’s start with the driver’s race gear (safety wear). If you have a “lucky” helmet from 1976, leave it at home where it’s safe. The number of brand-new, never-worn helmets in the box that come through Tech are often a surprise to even the seasoned inspector.

“Is this really the helmet you wear on the track?”

At SVRA we often walk the grid line as a final friendly look-see, give a handshake, and sometimes find a “lucky helmet” that belongs at home in the trophy room. It’s the same for gloves and shoes as well. In Canada, I saw a Tech inspector refuse a very old worn-out glove after carefully tearing off a finger and handing it to the driver with a friendly, “You need new gloves!”

Keep your gear current, clean and inspected. Patches and repairs should be done with Nomex thread. You don’t want a sleeve falling off in a two-second flash fire.

Keep your gear current, clean and inspected. Patches and repairs should be done with Nomex thread. You don’t want a sleeve falling off in a two-second flash fire.

Seat Belts: The proper lacing method per the manufacture’s or the SCCA guidelines are a minimum must do. At each event several cars are found with improper attachment points or, more often, miss-laced belt threading. If you worked on your belts, make certain they are rethreaded properly. Often heard explanation: “I’ll get them later.” Tech is not the place to say “later.” Bring the car complete and ready. At most events, a belt is found so poorly laced it can be stripped from the car with the Tech inspector’s single arm pull.

Seating: At every event a seat is found either not bolted in at all, or bolted with one or two bolts. The explanation: “I was too busy working on the new carb set. I’ll get it done before I go out.”

The same with numbers and or transponders. Bring it to Tech correct and ready!

Firewall: The firewall is your shield from a fuel or oil fire blowing into the driver’s compartment. One driver explained a real life experience from a fuel fire at speed as a “1,400° acetylene torch coming through a 1/8-inch pop rivet center.”

SOLUTION: close off all firewall engine compartment holes! Metal muffler tape is a quick trackside fix, but a visual clue next time it’s seen at Tech that a permanent repair wasn’t performed.

Fire Bottle: If it is a system, has the switch or cable been tested lately? If you have a halon bottle with no gauge, annually remove and check weight to spec, lube the cable, test the electric circuit, etc. Be prepared. One car went to pull the cable only to find it had rusted tight in the shield. Since he’d never had a fire, he never exercised the cable. Test and Lube!

If the fire bottle mounting is in a bracket, it should be removable so it can be used, not zip-tied down. One competitor brought a fire-bottle racer taped to a roll bar. When the problem was pointed out about quick removal, he returned with a butcher knife duct-taped to the bottle as a removal aid!

One can imagine the ensuing conversation to the accident-safety steward: “I was entering turn seven, when I saw a car hit the wall and then someone threw a knife at my car. Missed me by inches.”

I once saw a driver throw a clipboard out of his 90-mph racecar approaching a corner station. The driver said it was bouncing around and created a safety hazard. The corner worker described it as a “lethal Frisbee.” At SVRA the chief steward sent the driver to the corner station to have a reality check with the corner worker, and to give an apology.

Check your car over for loose tools, nuts, bolts, etc. The collection of tools and vice grips in the trackside tow truck would amaze even a Snap-On vendor… all found on the track surface as pick-ups!

Battery: Charging batteries causes another issue. They seem to go in and out of the car on a regular basis, but are not always rebolted down with the hot terminal covered, especially at the first two or three races of the season. Look at it each time like you never saw it before! Or better yet, have a trusted mechanic or fellow driver do a courtesy check-over inspection. Answer the question, “Is everything OK (perfect)?” “OK.”

I once saw an Alfa Romeo throw an unbolted battery through the trunk lid when the car was backed into the guardrail. Explanation: “I didn’t have time to bolt it down after charging it.” Yes, it was bolted down at Tech. Tech can’t re-Tech you after trackside service! Take the time, or skip your grid, until things are right.

Fuel Cell: A good Tech inspector will check the fuel cell feed and return vent line to see if they are tight. Several cars a weekend are found with hand-tight fitting that cause fuel starvation problems, and possible missed track time if not discovered at Tech.

Taillights: Never bring a car to Tech until you have checked the taillights or rain light. It’s the wrong place to make a repair, and always slows the inspection process while others wait because someone didn’t check ahead.

Tech expects you to check your suspension components, wheel bearings, and steering box before you come to Tech. Don’t tell Tech, “It’s always been loose,” or “They are all that way.”

I refused a car once until the steering-box shaft bearing could be rebuilt with a bearing the entrant had been carrying in his track-side tool box for two years. The driver was unable to drive the car without the 1/2 turn of free play he had gotten used to. At the end of the weekend, however, he’d shaved nine seconds a lap off his best prerepair times.

So there you have it! You’re the responsible party at Tech inspection. Tech only certifies you did the work.

At SVRA Tech, as with other vintage sanction race bodies, Tech strives to have a friendly, helpful inspection that is beneficial to the continued safety of vintage race weekends for all entrants. In this order…

BE SAFE—BE FAIR—HAVE FUN!

Driving suits—Know the facts before you buy

by Casey Annis & Jennifer M. Faye, Program Manager SFI

One of the most important pieces of any driver’s personal safety gear is the flame-retardant driver suit. Though entrusted with protecting some 90% of a driver’s body from heat and flames, it can be alarming to realize how little thought sometimes goes into a driver’s choice of suit. Given a choice between two seemingly similar 2-layer Nomex suits, many drivers will instinctually gravitate toward the less expensive version, oftentimes not realizing that there may, in fact, be as much as a twofold difference in the respective suit’s ability to protect the driver during a fire.

There are many things that influence what kind of suit one should buy, such as sanctioning body rules, track requirements, the type and speed of your car, etc. How do you put these factors together to ensure you buy the suit that is right for you? Some drivers look for a manufacturer’s name they know or trust, but even within any given manufacturer, there are numerous choices, sometimes offering quite varied protection and cost.

No matter how much you already know (or don’t know) about driver suits, you always have a standard that should guide you in your choice of a suit. That standard is the SFI Foundation Specification 3.2A for Driver Suits. Over the years, you may have noticed the black-and-white SFI patch on many drivers’ left shoulders at various tracks. This patch demonstrates that the manufacturer certifies the suit to meet or exceed the SFI specification.

What does this mean to the driver? It means that there is a way to differentiate the scientifically proven products from the untested products. A driver suit that is certified to meet the SFI spec has been laboratory tested and has passed the requirements of that test. Before getting into the details of the testing procedures, it is perhaps helpful to understand what the SFI Foundation is and what it does.

What does this mean to the driver? It means that there is a way to differentiate the scientifically proven products from the untested products. A driver suit that is certified to meet the SFI spec has been laboratory tested and has passed the requirements of that test. Before getting into the details of the testing procedures, it is perhaps helpful to understand what the SFI Foundation is and what it does.

SFI is a nonprofit organization established to issue and administer standards for specialty/performance automotive and racing equipment. This includes parts like clutch assemblies and fuel cells, as well as personal driver safety items.

The standards/specifications are created via a committee process. The technical committees are comprised of individuals from all facets of the industry. Through their expertise and research, a specification is drafted and then offered to all interested parties in the form of a public hearing. Once revised to the committee’s satisfaction, the spec is presented to the SFI Board of Directors for approval. If approved, the spec is published and made available to the public. Sanctioning bodies all over the world include SFI specs in their rulebooks and use them as minimum requirements.

The driver suit spec 3.2A tests a garment’s fire-retardant capabilites. The spec contains a rating system based on the garment’s capability to provide Thermal Protective Performance (TPP) in the presence of both direct flame and radiant heat. The purpose of the TPP is to measure the length of time the person wearing the garment can be exposed to a heat source before incurring a second-degree burn, i.e., skin blistering.

The TPP rating is the product of exposure heat flux and exposure time. These TPP results can then be translated into the amount of time before a second-degree burn occurs. The higher the garment rating, the more time before a second-degree burn. Listed in the table below are the SFI ratings with the corresponding TPP values and times to a second-degree burn:

SFI Rating TPP Value Time to 2nd -Degree Burn

3.2A/1 6 3 seconds

3.2A/3 14 7 seconds

3.2A/5 19 10 seconds

3.2A/10 38 19 seconds

3.2A/15 60 30 seconds

3.2A/20 80 40 seconds

Another test included in the spec is the after-flame test. This test discovers the amount of time it takes for a material to self-extinguish after a direct flame is applied to the fabric and then removed. This is called after-flame time and it must be 2.0 seconds or less for the layer of fabric to pass. Cuff material is also subjected to this test.

The TPP test can be used to evaluate multiple-layer configurations, as well as single-layer fabrics. The samples used in testing are assembled with the identical fabrics and layer order as an actual driver suit.

Other tests required by Spec 3.2A include thread heat resistance, zipper heat resistance, and multiple-layer thermal-shrinkage resistance.

A common misunderstanding about SFI ratings is that they represent the number of fabric layers in the garment. It is actually possible for driver suits with various numbers of layers to have the same performance rating, or suits with the same number of layers to have very different performance ratings. This is due both to the wide range of materials used by manufacturers today (i.e. Nomex, Carbonex, Kevlar, Proban, etc.) and by the many ways to which these can be combined and constructed.

A common misunderstanding about SFI ratings is that they represent the number of fabric layers in the garment. It is actually possible for driver suits with various numbers of layers to have the same performance rating, or suits with the same number of layers to have very different performance ratings. This is due both to the wide range of materials used by manufacturers today (i.e. Nomex, Carbonex, Kevlar, Proban, etc.) and by the many ways to which these can be combined and constructed.

Another testing area that is very important to a suit’s performance is radiant heat resistance, as the majority of racing-related burns are caused by heat transfer not by direct-flame contact. This point is very important when choosing a suit, because some materials, such as Carbonex, are very flame resistant, but very poor at resisting heat transfer. An extreme example would be making a driver suit out of stainless steel. Yes, the suit would be fantastic at keeping the flame off the driver’s body, but the material would still transfer the heat in such a way as to cook the driver (like an oven!).

Interestingly, insulation is the best way to prevent this kind of heat-transfer burn. Using specially woven fabrics and/or multiple layers of fabric helps keep the heat source away from the skin longer because each layer creates air gaps that have to literally heat up before the heat can transfer to the next layer. These extra seconds gained with each layer are precious to a driver trying to escape from a burning car.

Another key way to obtain extra air gaps is to wear racing underwear. Nomex underwear should be worn with every type of driver suit, especially single layer suits because it will double the protection time (+3 seconds). The 3.2A rating does not include underwear in it’s time-to-burn estimate. However, Nomex underwear has its own certification process through SFI Spec 3.3 for Driver Accessories and undergoes the same TPP and flammability tests as the driver suit outerwear.

A suit’s insulation capability is also affected by the fit of the suit on the driver. A suit worn too tight will compress the air gaps and allow heat to reach the skin faster. While none of us ever wants to admit that our suit is getting too tight, it is actually very dangerous to race with a suit that doesn’t fit properly.

There are other things you can do besides finding a correct fit to optimize the protection performance of your driver suit. Ideally, you want to keep your suit as clean as possible. Check with your manufacturer’s cleaning directions as each suit may be different. Most suits are machine washable but many manufacturers usually recommend dry cleaning. It is absolutely essential to read the care tag on the garment and closely follow the manufacturer’s instructions. In any case, it is very important to keep your suit away from any heat source including the dryer or excessive sun exposure as even minimal heat exposure can significantly impair a suit’s performance rating.

Avoid wearing your suit while working on the car. Not only would you be ruining an expensive piece of equipment, but you would essentially be inviting a fire to burn you. Grease, fuel, oil, and even cleaning fluids can soak into the fabric and support the flames of a fire, causing high heat. Fluids soaked into a suit also produce steam when exposed to heat and cause liquid vaporization burns.

If you are ever involved in a fire—or burn a spot on your suit on say an exposed exhaust header—discard your suit and get a new one. Even the smallest singe is a weak spot in the material and can cause a problem if exposed to fire again. Proper maintenance of a driver suit will help extend its useful life and provide you with years of protection.

Another SNELL Cycle, is this really necessary?

by Kyle Kietzmann, General Manager Bell Helmets

The 2006 racing season marks the beginning of yet another Snell cycle, causing racers around the world to look inside their helmets to see what their rating is and ask, “Is it really necessary to update my helmet?” Some people believe the introduction of a new standard is simply collusion between the helmet manufacturers and Snell to force people to buy new helmets. Others will tell you it is an absolute necessity to insure proper head protection and safety among competitors. To answer the debate, ask yourself a simple question, “How much is my head worth?”

I think we can all agree that it is worth a lot and should be protected. To best protect your head, Snell and most helmet manufacturers recommend replacing your helmet every three to five years. Why has this become the guideline and the five-year rule the industry standard?

There are two reasons: all helmets and the materials they are made of will degrade over time or through continued use and new technologies continue to be introduced that improve helmet performance.

No matter how well engineered, all products and materials break down over time. Helmets are no different. A helmet is built to absorb energy during an impact through the fracturing or delamination of the outer shell and the crushing of the helmet’s inner liner. Even simply dropping a helmet onto the ground starts this energy-absorbing process and reduces the helmets overall effectiveness to manage energy.

The other factor is that as the speeds and demands of the sport increase, the safety technology has to keep pace. Most advances in helmet materials and technology are driven by the aerospace, packaging, and automotive industries. As new innovations are introduced, helmet companies continue to engineer these new technologies into helmet construction in order to improve performance and the ability to manage energy.

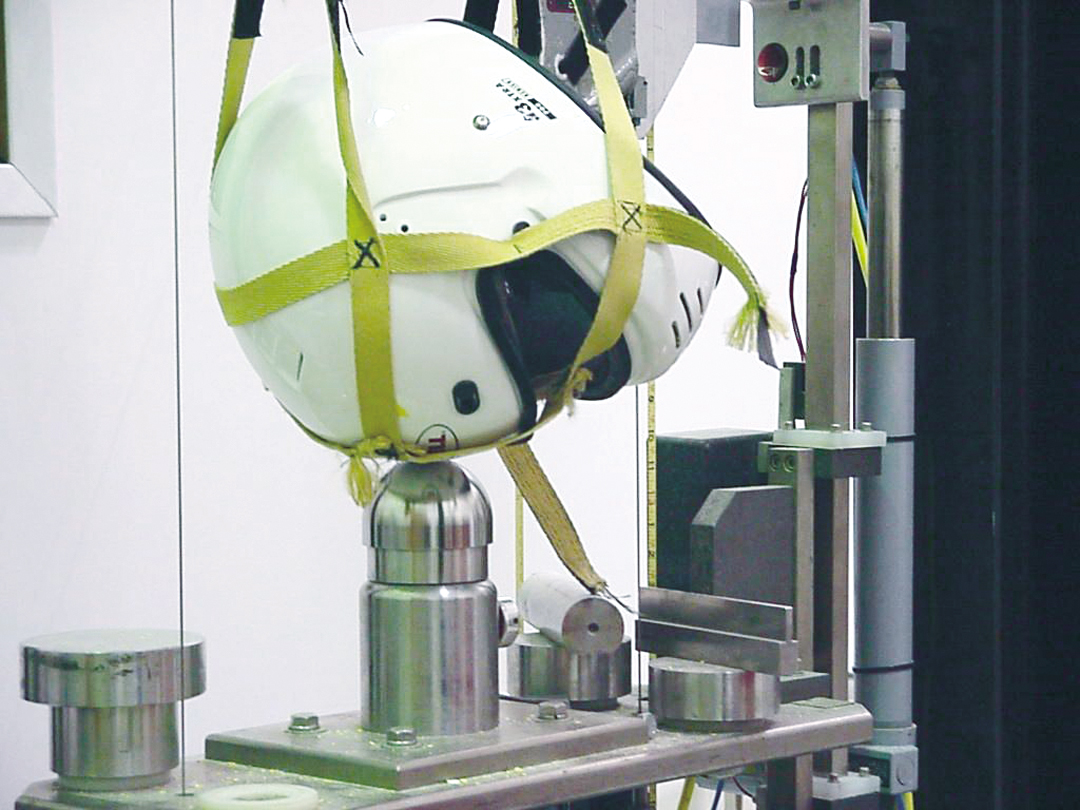

Snell recently released the updated 2005 M, SA, and K standards for racing and other power sports in October 2005. The latest standard reduces the allowable G levels from 300 G’s to 290 G’s and lowers the test line on the side and front, expanding the area the helmet can be tested. There is some confusion regarding the differences between the various Snell standards. All of the standards have similar impacts within the Snell test zone (the impact area). To conduct an impact test, Snell places the helmet on a metal head form that simulates the average weight of the human head and drops the helmet onto a series of anvils (hemispherical, flat, and edge) to simulate real-world impact surfaces. There is an accelerometer inside the head form that calculates how many G’s the head sees during an impact. In other words, how many G’s the helmet did not absorb and were transmitted to the driver.

The first impact is from a height of 3.2-meters and the second impact is from 2.3-meters. This simulates a multiple-impact accident and in both impacts, the maximum energy the head sees cannot exceed 290 G’s— this being the threshold that is viewed as being a survivable impact. Snell also performs these tests in several temperature conditions including cold, ambient, hot, and wet to simulate different racing conditions. Beyond the similar impacts, the major differences between the ratings are as follows:

M stands for Motorcycle applications or forms of racing that do not require a fire-retardant interior and also requires a larger eyeport for more peripheral vision.

SA stands for Special Applications and has a fire retardant component requiring the interior and exterior to self-extinguish after being exposed to direct flame and also has an additional roll bar anvil impact.

K stands for Karting and is the same as the SA standard except it does not have to be fire retardant.

The type of Snell rating required depends on the sanctioning body. Most racing organizations are starting to require SA rated helmets. In addition, most sanctioning organizations will allow a three-to-five year grace period before requiring competitors to update their helmets. For example, with the introduction of the new Snell 2005 standard, most will now require at least a Snell 2000 helmet. It is always best to check with your organization to see what rating will be required. It is also important to select a helmet that has the necessary features for your form of racing and fits your head properly. Good fit is an important part of the retention system of a helmet, insuring it does not shift and stays firmly on the head during an accident.

Given the new focus on racing safety, the helmet standards published by Snell will continue to become more stringent in order to advance safety and protect drivers. Helmet companies will continue to advance protective technology to make racing safer. So, the conspiracy theorists can rest easy. There is something to this Snell cycle thing after all. Be safe, replace your helmet. Your head is worth it!

Kyle Kietzmann is the General Manager of Bell Racing Company, he can be reached at [email protected].

Head and Neck Restraints— Should everyone own one?

by Trevor Ashline, LFT Safety Products

Head and neck restraints are one of the latest safety innovations that have found a home in all professional racing organizations within the US and overseas. Controlling the head and neck motion in a racecar becomes paramount when the rest of the body is restrained from the seat and seat belts. A set of 5- or 6-point seat belts, when properly mounted, are very effective at restraining the body. The only other vital part of the body that is then left unrestrained is the head and neck.

For the first four to five years of head-and-neck-restraint testing, the unwritten industry standards were based on 50-G impacts in the test lab. Testing and approval of head and neck restraints were done at both Autoliv North America and Wayne State University. Both labs were conducting 50-G impacts based on the best information available at the time. As a comparison, passenger car testing is normally done at approximately 30 mph and 30-G. Dale Earnhardt’s impact was estimated at 42-Gs, with a 38 mph change in velocity.

In 2001, the HANS device and the Hutchens device were both mandated for use in NASCAR’s top series as a result of testing conducted by NASCAR. Other sanctioning bodies and track owners were soon quick to embrace this new technology. This trend has continued over the past five years to include not only U.S. sanctioning bodies but others throughout the world, including Formula One.

Testing on head-and-neck restraints has grown at a surprising rate. The new SFI 38.1 head-and-neck-restraint standard is based on a 70-G impact on a laboratory test sled. Information from data recorders now mounted on racecars in NASCAR, IRL, and CART have also given excellent feedback to engineers and biomechanical researchers studying racecar crashes. As a result, NASCAR and SFI got together in the fall of 2004 to come up with a new testing standard that could be used by sanctioning bodies to evaluate the effectiveness of the various new head-and-neck-restraint systems. The set-up used for the SFI test is the most involved and expensive test in all of SFI’s long list of certifications. As a footnote, the SFI head-and-neck-restraint test has the highest impact load of any SFI spec for passenger compartment-related products. An example of the severity of this new test is the finding that SFI-certified 6-point seat belts have been known to break during the head-and-neck-restraint test! Everything about the dummy set-up is controlled to make sure it is a fair test for everyone and the head-and-neck restraint is properly evaluated. The tests include 3 straight frontal tests and one 30-degree frontal test—all at 70-Gs. The restraints are evaluated on effectiveness in reducing neck tension and controlling neck motion using a value known as Nij. If the restraint passes the first two straight frontal impacts with a neck tension value of less than 3,200 Newtons (N) of force on a 4,000-N scale, the manufacturer is allowed to skip the third frontal impact and move on to the 30-degree angular frontal impact. All three of the currently approved SFI 38.1 head-and-neck restraints have passed using this exclusion. They are the LFT Technologies R3, the Safety Solutions Hutchens II, and the HANS device.

With an understanding of the SFI 38.1 certifications, we will only discuss these three products in this article. These restraints represent the latest and best head-and-neck restraints on the market. A lot of head and neck restraints from around the world have been tested to the SFI rules, but only these three have been proven to perform to this extreme level.

All three of the currently SFI-approved restraints have a number of things in common: (1) they all ride with the occupant, (2) they all transfer the head load to a good anchor to control the neck forces, and (3) they all attach to the helmet in two locations. How they achieve these three goals is where the restraints differ.

The LFT Technologies R3 is a full carbon fiber and Kevlar restraint that uses straps to attach it either to the driver around the chest or it can be mounted in the seat. The carbon fiber part of the restraint goes straight down the wearer’s back. It is simply a lever arm that rotates about the wearer’s shoulders. A short lever arm transfers the head load to the pivot point of the restraint and the load is resisted by a long bottom lever that attaches either to the bottom of the chest cavity or the seat belt buckle. When mounted to the seat using Velcro to hold it in place, the chest strap is replaced by a strap that connects it to the seat belt buckle at its bottom anchor. In either case, a molded foam insert is used in the back of the seat to give the restraint a place to set into when you buckle in. One nice aspect of the installation is how the restraint will “disappear” into the seat back and is undetectable when a driver belts into the racecar.

The Hutchens II is a cross between the carbon restraints and the original Hutchens device used in NASCAR for four years. The device uses a small section of carbon fiber that acts as a spacer to locate the helmet tethers and drape the Kevlar strap harness over. Since the carbon part of the device is not used to directly carry the head load, it can be made much lighter and, therefore, more economically. The Hutchens II straps to you like the original Hutchens, but it uses a wider tongue to attach it to the seat belt buckle and improved leg straps. The benefits of the Hutchens II are that it can fit into a variety of seat back configurations without being uncomfortable, no matter the seat angle, and that it cannot come loose from the user. Even after flipping and tumbling a number of times, the Huchens II will still be strapped to you and functioning.

The HANS device is a full carbon fiber yoke-style device that rides around your neck and uses the seat belts over the yoke ears to transfer the head load. The function of the device is to stay with the seat belts and allow the wearer to slide under the device until it is set in back of the wearer’s head, when the tethers start loading. As the head loads the device, it pivots about the wearer’s upper chest and shoulders while transferring load to the shoulder belts. The device is the brainchild of Jim Downing and Bob Hubbard of Hubbard Downing Inc. and its original patents date back to the mid-’80s, when the two derived the original prototypes. Since then it has been studied and modified into its current configuration. The device is used and recognized throughout the racing industry.

In the world of head-and-neck restraints, a number of things need to be considered when deciding upon which restraint is correct for your application. With the full carbon restraints, the R3 and the HANS, the seat back angle and seat type must be considered in order to properly fit the device into the seat. For the R3, only the seat back angle need be considered. There are four models currently available from straight back seat to a contoured 70-degree layback commonly found in a stock car or a full lay-down model found in a formula car. For a HANS device, there are similar requirements of knowing the seat back angle from a 0-degree (full-upright) seat back to a full lay-back found in a formula car. The headrest will also need to be set back or relieved to allow room for the restraint. The third restraint, the Hutchens II is a cross between a strap harness and a carbon restraint. The Hutchens II uses the smallest piece of carbon fiber which means that it will fit into the widest range of seats without any type of modification.

The next thing to consider is the amount of upper-torso movement that can happen in your racer when in an impact. The HANS device which was developed for tub-style F1 and Indy cars does not like a lot of side-to-side, upper-body movement before the restraint frees itself from the seat belts which restrain it. It is highly recommended to use a strong shoulder and headrest in your seat when using this configuration. The R3 and Hutchens II were developed with this in mind and do not rely on the seat belts to generate their restraint forces. In this respect, they are better for a more spacious cockpit configuration or seating that will allow a lot of upper-torso movement.

In closing, I would like to point out the importance of the head-and-neck restraint in controlling the head and neck forces in a racing accident, but never forget that the head-and-neck restraint is only one component of a properly done safety system. Just like a chain, your restraint system is only as good as its weakest link. Don’t forget about a quality seat with shoulder and head support (mounted high in the shoulders) and a properly mounted set of polyester seat belts. Attention to detail is the most important thing to pay attention to. All of these things contribute to a system that can potentially save your life in a racing impact.