1990 Penske PC19-Ilmor Chevrolet

I first saw Roger Penske racing a Maserati Birdcage at Lime Rock Park in Connecticut. He won a superb battle with Peter Ryan’s Lotus 19. Penske was smooth…in every way. He was young, good-looking and very determined. My interest was also sparked by the fact that he had just finished at Lehigh University, where my father had gone. Penske was smart, and it seemed like he and Ryan were two guys who would go wherever they wanted. I was there at Watkins Glen in 1961 when they both made their F1 debut at the United States Grand Prix, and finished 8th and 9th. Then Ryan was killed in a Formula Junior race at Reims in 1962 and his chance was gone. Roger Penske’s star has never stopped ascending.

This story is complex. It’s about the immense success of Roger Penske, his drive and determination and how he came to dominate Indycar racing among other things. It’s also about Paul Morgan who, along with Mario Illien, had a dream about what their engines could do. Penske’s vision allowed him to see what the Morgan-Illien partnership—Ilmor—was capable of. And it is also about the late Paul Morgan’s son Patrick, who helped to keep his father’s memory alive by finding, restoring and running one of the cars with the most successful of all Indy racing engines of modern times, the Ilmor Chevy 265A. The story is a tribute to some fine people, to technical brilliance and to dogged determination.

The Penske story

Roger Penske started as a racing driver and almost ended up owning motor racing, such was the scope of his influence and business ability. It began reasonably modestly. Born in 1937, as a teenager he was buying cars, repairing them and selling them—some 32 cars in a ten-year period from the family home in Cleveland. This financed his own racing career at the start. He had an old Porsche RS in 1958, which gave way to a more potent RSK purchased from Bob Holbert. Penske worked his way through the SCCA championships; beating Holbert himself along the way.

He joined Alcoa after leaving Lehigh, and that had an influence on the company as it became one of his long-time sponsors when he turned professional in 1962. He drove in two Grand Prix races, both at Watkins Glen where he was 8th in a Cooper in 1961 and 9th in a Lotus 24 in 1962. His exploits with the F1 Cooper-turned-Zerex Special are legendary, and he sealed his road to fame by winning both the Nassau Tourist Trophy in a Corvette Gran Sport and the Nassau Trophy in 1964, sharing the Chaparral with Hap Sharp. He raced widely in Europe, including Le Mans where he shared a NART Ferrari 330LM TRi with Pedro Rodriguez in 1963, a car that they put on pole but retired after 113 laps. He retired as a driver in 1965 to concentrate on “business,” which, of course, also included motor racing.

In 1965 Penske started up his first Chevrolet dealership and the formation of Penske Racing, which was to enter just about every form of international motor racing including Formula One. Penske entered a McLaren for his star driver Mark Donohue once in 1967, but the team contested F1 as a constructor from 1974 until 1977. Penske Racing was in NASCAR, Trans-Am, Can-Am, F5000, endurance racing and most notably, Indycar racing. Penske first ran a stock-block Eagle for Donohue in 1968 before the team made its 1969 debut at the Indy 500, and within three years his had become the top team at the Speedway. Roger Penske himself had turned down the offer of a rookie test at Indy, and that test went to another “rookie,” one Mario Andretti.

The 1969 entry under the name U.S. Racing was for a Lola-Offy that finished 7th. Donohue was again on the second row of the grid in 1970 with a Lola-Ford, this time coming 2nd. The following year he had progressed to the middle of the front row with a McLaren-Offy, but failed to finish. In 1972, Donohue was 3rd on the grid but finally brought the McLaren to Victory Lane, and the entrant was now Roger Penske Enterprises.

Enterprising Penske

Penske’s Indy expansion brought two cars to the Brickyard in 1973, an Eagle-Offy for Donohue on the front row and a McLaren-Offy for Bobby Allison, neither of whom did well. The team ran cars, usually McLarens, at the 500 every year for a range of drivers. Mark Donohue was killed at an F1 race in Austria in 1975, and much of Penske Racing had revolved around him for a long time, but despite that key loss the race effort grew and grew.

The Penske chassis

Three Penske chassis appeared at Indy for the first time in 1978 for Tom Sneva, Mario Andretti and Rick Mears, all with Cosworth engines. Sneva in the PC6 finished 2nd, and another Penske “product,” a dedicated Penske Indycar chassis, had been born. There were nine Penske-Cosworths in 1979, including Mears in the winning PC6, 11 in 1980 including the 2nd- through 4th-place cars, 12 in 1981 as Bobby Unser won in a PC9, and so on for several years. In 1984 every car but one was Cosworth powered, as Mears won his second 500, this time in a March. Penske did not run Penske chassis at Indianapolis for five years, though he continued to enter Ilmor Chevrolet-powered Marches, winning with Danny Sullivan in ’85 and Al Unser in ’87. The Penske PC17 appeared in 1988, with Mears winning again and Unser 3rd. Ilmor’s Chevy engines had arrived in strength.

Enter Ilmor

“My father’s involvement with Roger Penske started,” relates Patrick Morgan from behind his desk at Dawn Treader Performance’s factory at Sywell Aerodrome in Northamptonshire in the English Midlands, “when he was running the development program at Cosworth on the DFX engine and my father came up with a list of improvements he wished to make—a list of 26 items—because he was concerned that other manufacturers were going to come into the Indycar series which at that time was dominated by Cosworth. Keith Duckworth, who was commercially minded, decided that it wasn’t necessary to have these changes at that time in the early 1980s, and my father and Mario Illien, who was the designer of the Cosworth DFY engine, approached Roger Penske and said they would like to put an Indy program together.

“They said they thought they had some ideas that would be an improvement on the Cosworth engine. They asked whether he would back them, and Penske made his mind up very quickly and said he would. At the beginning of 1984, Ilmor was started, and had a two-year gestation and design period on the 265A.” Contrary to popular belief, this was a very different engine from the DFX, though some people had said it was similar or was a clone, but aside from being a 90-degree V-8, its architecture is very different. It has a single-part cylinder head where the DFX had a two-part cylinder head; the gear train is at the back of the engine instead of the front, and the pump arrangement is significantly different, so it is by no means the same engine.

“The vee-angle happened to be the same, but there is a very interesting story attached to how that came about,” explains Morgan. “Mario and Dad couldn’t decide what the vee-angle should be; they couldn’t decide whether they wanted to go for a 70- or 80- or 90-degree vee, so they engaged the services of my three-year-old sister Lucy, and asked her what she thought. She said ‘90,’ so it was 90! Honest, a three-year-old decided!”

After a great deal of research and hard work, the 265A went into its initial test phase, originally running with mechanical injection with a pancake motor and so-called potato cam, which is a system Paul Morgan had developed with the DFX where not only was the metering unit operated by throttle angle as it is with BDAs and BDGs, but it also fuelled for rpm which was a big weakness in the standard Lucas mechanical injection system.

In the late 1980s the engine moved on to electronic fuel management, and although the engines were really driveable and comparable to, if not even better than, the DFX on performance, they turned out to be inherently unreliable, which came down to a torsional vibration. Patrick says “this was figured out to be a problem early on, but it took a long time to work out how to cure it. I think Dad and Mario both had a difficult time convincing team owners that the solution they came up with was going to be a ‘light-switch’ fix, but it was.

“Each bank carried in its gear train a rotary mass damper similar in concept to a j-damper as used in Formula 1 suspension systems. It’s like that used in an F1 chassis today, it’s a weight with four free-floating components which spin up and down to balance the torsional vibration created by both the crankshaft and the stab torques of the valves, and it pretty much doubled the life of the engine. It made a huge difference and they tried quite hard to hide it. By 1988, 1989 and 1990, the engine was incredibly reliable and had won two or three Indy 500s by that stage. But it had taken a massive effort to get that far.”

The 265A engine first appeared in a car, a March chassis, at Bruntingthorpe in the UK in 1985. At that time, Penske was running a parallel program. The engine was designed to be compatible with a Penske PC15 which was a difficult car, and there was a lot of talk that the engine was at fault. Eventually Roger Penske purchased a March chassis and everything quickly came together as the whole package became a lot better. Penske was running both March and Penske chassis as he had done in the past when he ran his own chassis in parallel to Lolas. All the design and work on the engine was done in the UK as Ilmor Inc., the American arm of Ilmor, didn’t exist before 1990. The PC19 was one of the first cars genuinely looked after by the Ilmor Inc. trackside group, although the engines at that time were actually assembled by Franz Weis at VDS Racing.

The engine ran successfully in the PC17, the first Nigel Bennett-designed car, and that is when things really started coming together for the Penske-Ilmor combination. The PC18 and PC19 were evolutions of that concept, with continuous refinements being built into the cars.

Penske PC19-009

Our test car, PC19-009 was Emerson Fittipaldi’s spare and test car in 1990, and Emerson put its sister car on pole at Indy that year. The chassis was not raced in 1990, but was much used as a spare and was driven in practice by Emerson at Indy. It was first raced in 1991 by Paul Tracy when Roger had decided to run a three-car team. In 1991, Penske put a small group together to run Tracy at the Michigan 500 and a few other races, in blue and white livery, much like the Marlboro livery but done for Mobil Oil. Tracy, the Indy Lights champ, had started the 1991 season with Dale Coyne before the Penske opportunity arose, and it had been initially thought that he would be a test driver for a season or two. It was a very significant car for Tracy, as it was his first truly competitive Indycar. The chassis type was very successful, it was a very flexible car, and proved to be quick on both ovals and road courses.

However, Tracy managed to have a big accident at the Michigan race in August—in chassis 08—and ended up with a broken leg, sidelined for many weeks. Tracy returned to drive 09 in October for the two last races of the season. On October 6, Tracy drove 09 at the Bosch Spark Plug Grand Prix at Nazareth in Pennsylvania, a tough 225-mile race. He started 13th and drove a hard but steady race to come home an impressive 7th in what was still his rookie year. On October 20, the CART circus was in California on the demanding Laguna Seca road circuit, and Tracy put the car 11th on the grid and was initially running very well when overheating forced him to retire. Tracy, who had originally been seen as a somewhat innocent-looking, bespectacled “new boy,” was to continue in a test role for Penske in 1992, but ended up doing 11 races, the start of an 18-year career in Indycars.

After 1991, PC19-90-09 was painted up as a show car. It was in white colors when Patrick Morgan bought it, but it had “Mercedes” on the side though with no other race mementos, so was presumably repainted in 1994/1995. Morgan bought it in 2003, and the chassis was initially taken apart and reassembled by Penske in Reading, Pennsylvania, during the last days when the team was based there before the entire operation moved to Charlotte, N.C., where all of Penske’s racing activities are now consolidated under one roof. Patrick rebuilt the engine in Northampton with his Dawn Treader staff, and looked after the electronics. It was very much a joint transatlantic venture:

“You can imagine trawling everyone’s memories over the phone; it was kind of exciting but we did manage to get it all together. It was a big job, and was the beginning of DawnTreader as it is now. It was done in the evenings in a very cold hanger on the other side of the Sywell airfield, where the cylinder block had to be heated to turn the crank in its bearings. It was very challenging but rewarding when we fired it up for the first time. The major issue was the electronics, but the engine itself was relatively straightforward. Being an engine that was for customer use and had been developed over a number of years, it was fairly well thought out, but the electronics required help from Ilmor which had kept some of the old software. We used an old laptop, but we did get it all to work.”

Patrick admits it was very much a sentimental journey finding and restoring this car. He wanted something from the peak period when his father’s engine was the best of the lot. Penske was very helpful in finding the car, and it was pretty emotional for Patrick to drive it for the first time at Goodwood in 2004. He shared it with Christian Fittipaldi, with Emerson in another car sitting alongside. Arie Luyendyk has had a run in it as well. It’s a great tribute to Paul Morgan, who was tragically killed in the crash of one of his vintage aircraft at Sywell in 2001.

Driving the best

The 1990 season was one of very diverse and advanced technology for Indycars. The engine war had been revived, and a great deal more sponsorship money had been pumped into the series. Roger Penske had sold off his 1989 PC18s, but customers would not be getting their hands on the refined PC19. Buick, Porsche, Judd and Cosworth would be challenging the Ilmor Chevy on the engine front, but the reliability that Morgan and Illien had established in 1989 had brought orders from Newman/Haas and Galles-Kraco. A great deal of effort had been going into ensuring the long-term future of Indycars.

Rick Mears won the season opener for Penske at Phoenix, while Al Unser Jr. won at Long Beach in the Galles-Kraco car. In practice at Indy, the Penske team was dominant. Fittipaldi drove this car and what would eventually be his race machine. In the opening practice sessions he set the fastest time ever recorded at the track, 227 mph, though this was later beaten by Unser. In qualifying he then set the fastest one- and four-lap qualification times of more than 225 mph. Fittipaldi ultimately finished 3rd as Luyendyk won for Doug Shierson’s team—powered by Ilmor engine #79.

I had engine number 171 sitting behind me as we went through the lengthy pre-running process that is essential to getting a winning performance from such a machine. It was a privilege to be allowed to experience just what it is/was like to run a good Indycar and, of course, this process helps the longevity of the engine.

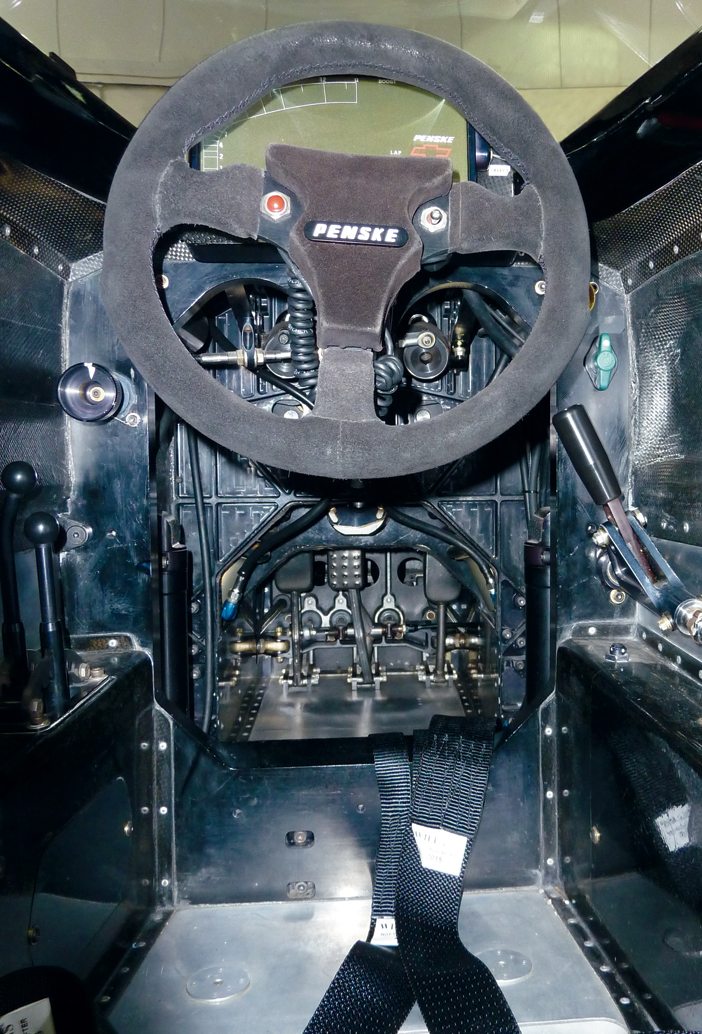

I squeezed down into the narrow cockpit where the seat had been removed to accommodate hips slightly wider than the last person who sat here. Next to the car the pump arrangement that heats and recirculates the water through the system was buzzing away. It was already a cold, damp and grey English day and the car needed to be well warmed up before venturing out onto the kilometer-long Sywell airfield for the test. The cockpit was indeed a squeeze and the driver sits well down in the half aluminium honeycomb/half carbon fiber monocoque. There is plenty of lateral support and just enough room to do what is necessary. The boost knob is black with a white indicator on the left side, there are levers for front and rear anti-roll bar adjustment and a knob for brake bias. The ignition switch is on the steering wheel, with a rain light switch behind, next to the extinguisher button. All the required information is on the digital panel, and I would be keeping a sharp eye on water temperature. We would be starting at 90 degrees and trying to keep it at a minimum of 70 for the duration.

Once my feet found their way down to the pedals, it was clear the clutch and brake are very close together—a Fittipaldi preference I gather. Narrow shoes are mandatory! The gear lever is to the right, operating a Penske 5-speed box with a familiar left and back for first gear and then the standard H-pattern. The car was running on Avon slicks, 350/720-R15 on the rear and 275/655-R15 on the front, with the period-proper Goodyear yellow painted onto the tires so the car looks just right with its Marlboro, Bosch, CART PPG and Hertz decals, as well as the other sponsor logos.

Some hours passed to allow the weather to settle to a manageable level, and until the local school was over for the day as the noise from this engine is impressive—louder than the aircraft that use the airstrip. Fortunately we were given a period of no flying to assist my concentration!

Finally it came time to get down to business. Mark located the external starter at the rear, Kris spun the fuel pump drive and Patrick gave the signal to switch on. The Ilmor Chevy instantly burst into throbbing life and we held it at 3000 rpm to get back up to 90 degrees. While concerned about getting off the line, Patrick was helpful in saying “just spin the wheels and don’t slip the clutch and it will go;” which it immediately did.

It is quite amazing to go out onto a long strip of road—or airstrip—with no markers or anything to help you judge distance, and just extract the most you can from 750 bhp. The boost was not on full though Patrick, bless him, said to “turn it up” if so desired. The first few runs were to get the feel, and there is plenty of that, most of it coming up through my unpadded backside. Though this is a car capable of 240 mph, it is low-geared in its present life, with 1st and 2nd very close and 3rd, 4th and 5th all going to come into play.

The gearbox took some getting to grips with. It’s one of those boxes where if you don’t really hesitate it all works well. But I was trying to get my bearings and found it hard to find 4th a few times and had to slow down and start again. Once that is mastered, however, it’s magic and you can fly up and down the box. However, this is an Indycar and although it did do road races for which the box is brilliant, it was the high-speed running in top gear that was what this car was all about. After a few tentative laps and two stops to get it all warmed up again, Patrick said, “you have to do a hard run to feel the turbo go to work and to really experience this car.”

So, as the sky darkened, I lit up…well almost…the tires and shot down the runway, into 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th and aiming to get over 10,000 rpm in top. That’s something over 165 mph with this gearing, but you are there in seconds, and that is an incredible feeling. Think then about running at 200 mph in traffic. The car is stiff and very precise without being scary. At no time was I worried that it would shoot off line. Torque is amazing and it pulls and pulls in fifth gear. I tried looking in the mirrors to imagine what it was like to see someone coming up behind you. Think of doing this in a bunch of 10 or 12 cars. At high speed I had to hold the line…the airfield bumps were more than evident. The Alcon 6-pot brakes work well, though I didn’t really test them hard. The turning circle was small enough to swing around and head back the other way. Patrick had okayed using 12,000, but I never got there as the car was already flying, its Ilmor thumping away behind me, Penske around and beneath me.

Emerson Fittipaldi once said, “all my success in America came with Ilmor, first from Chevrolet and then Mercedes. What else can I say?” Amen to that!

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: Monocoque: lower half aluminum honeycomb, upper half carbon fiber

Suspension: Double wishbone-pushrod, with rocker-operated coilover dampers and adjustable front and rear anti-roll bars

Engine: 90-degree 265A Ilmor Chevrolet V-8, 2.65 liters (161.5 cu.in.); 88.6 mm bore x 54.5 mm stroke; 4 valves per cylinder; boost maximum 1.62 bar (48 inches Hg); fuel capacity 35 US gallons methanol; dry weight 325.6 lbs.

Power: 720 bhp @ 10,750 rpm, max rpm 12,500

Ignition: MSD unit

Gearbox: Penske 5-speed

Brakes: Alcon 6-pot calipers working on 4 ventilated cast iron discs

Tires: Avon 275/655 R15 front and 350/720R15 rear

Resources

We want to thank Patrick Morgan and his staff, Mark, Kris and Jim at Dawn Treader Performance for their unceasing help with this test, and for their valued friendship. www.dtperformanceltd.co.uk. Also, thanks to Michael Bletsoe-Brown and Sywell for the use of their airstrip.

Ludvigsen, K. Prime Movers–Ilmor Racing Engines Transport Bookman Publications London 1995

Popely, R. Indianapolis 500 Chronicle Publications International Illinois USA 1998