Few would argue with the notion that Tazio Nuvolari was one of the five greatest racing drivers of all time; some would even say the greatest. But as the years pass, the number of people who saw him race diminishes, so how can we really know? It is easy to parrot the biographies, of course, but most of them usually recite blow-by-blow race reports— some flawed at the time of writing up to 70 years ago, some blurred by being re-told time and time again—and his results.

Few would argue with the notion that Tazio Nuvolari was one of the five greatest racing drivers of all time; some would even say the greatest. But as the years pass, the number of people who saw him race diminishes, so how can we really know? It is easy to parrot the biographies, of course, but most of them usually recite blow-by-blow race reports— some flawed at the time of writing up to 70 years ago, some blurred by being re-told time and time again—and his results.

And what results! Nuvolari competed in 229 car races, won 57 of them including 16 Grands Prix, two Mille Miglias, two Targa Florios, two Tourist Trophies, the 1936 Vanderbilt Cup, the 24 Hours of Le Mans and put up 50 fastest laps. It was the same with motorcycles. Tazio ran in 124 bike races, won 39, scored 39 class wins and set 40 fastest laps. Before the Second World War, he was known as the fastest man on earth.

But why was he so successful? What was his secret? Was his driving technique really so different? What was he like as a person? Was he a womaniser? And what did his wife think of him?

To find out, Vintage Racecar boarded its very own time machine and roared back across the years to “talk” to some of the men and women who really knew Tazio Nuvolari well, saw him race, raced against him, loved him or, like the rest of the world, simply applauded him from the roadsides and circuit stands as he blustered by. We wanted to know why this scrawny, 5ft 5in mini-Italian with the trademark long jaw worked his way into the all-time top five, maybe even to head it.

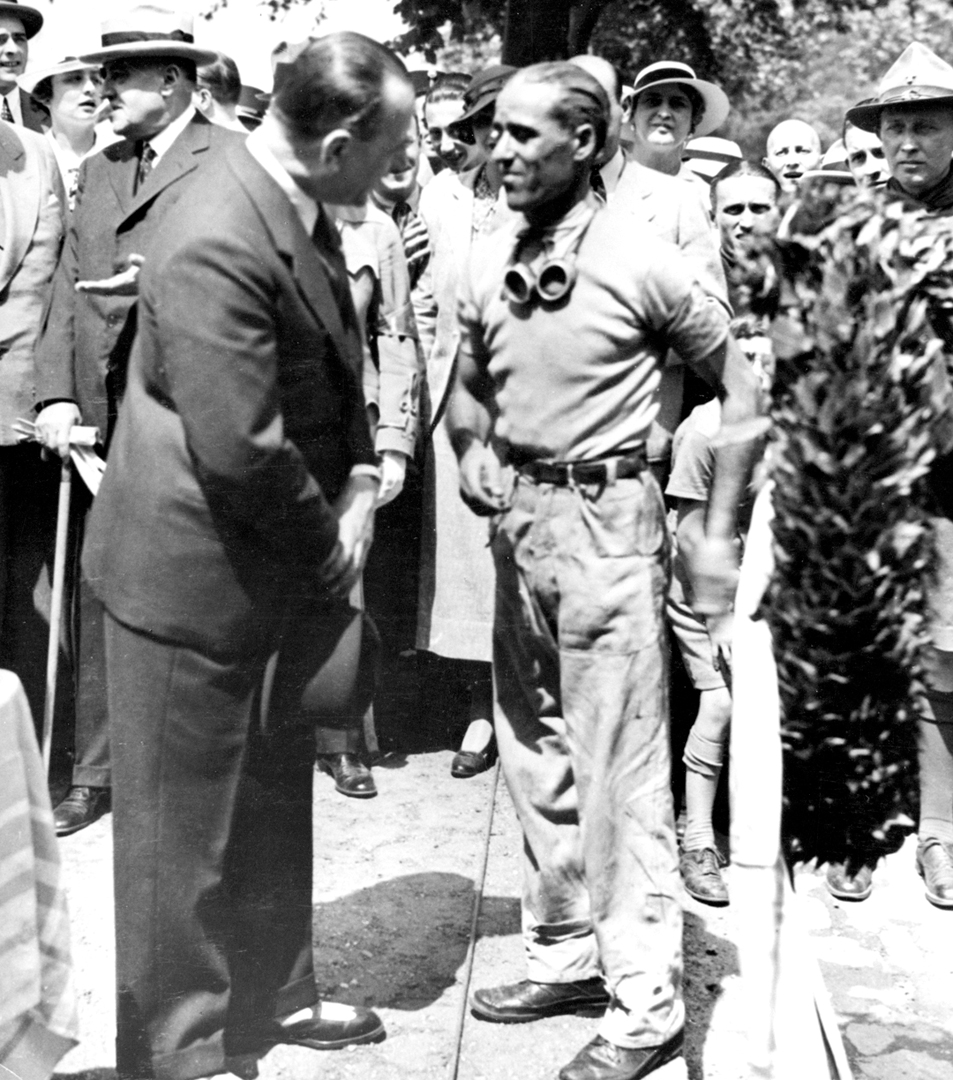

Giovan Battista Guidotti and Tazio Nuvolari won the 1930 Mille Miglia together for Alfa Romeo. “We were friends and I admired him greatly for his unique driving style,” said Guidotti. “What was his speciality? Going over the limit in a controlled skid. Nuvolari always ran the engine at maximum usable revs. Before a corner, he quickly lifted his foot from the accelerator to exploit the engine brake, saving the brakes themselves, which had limited efficiency in those days.

“When he got to the corner he accelerated immediately, cadence braking to ensure the anchors did not overheat. He heel and toed without ever creating wheel spin. The front and rear wheels were constantly parallel and he checked the highest entry speed of the others yard by yard, to be just visibly over the limit with his car, which moved to the outside in a mild drift. But it was a drift he controlled by sawing away at the wheel and blipping the accelerator. Thanks to the wheels being parallel, he could shoot out of the corner faster than anyone else and already be lined up for the next one.”

Gigi Villoresi was another expert observer. “Tazio Nuvolari had a driving style that was unequalled: it was different from the others’. I had occasion to observe him at the Circuit of Montanero in Italy. I was driving a 1500-cc Maserati and he passed me before a tight left-hander. I followed him from 50 yards back and I had the sensation that, given his high speed, he would soon go off. But not a bit of it. He went into the corner in a completely different way: he had his foot hard down on the accelerator, did a little cadence braking and the nose of the car was pointing straight at the apex of the bend. Then he did a complete drift and in that way had the car perfectly aligned with the road, corner after corner.

“His style had no equal and nobody was able to reproduce it. Anyway, you could only do that kind of thing with the cars of those days, due to their rigid suspension, independent wheels and very narrow section tyres, which were inflated to high pressures.”

Giovan Battista “Pinin” Farina, the great Italian car stylist, first saw Nuvolari race in that exuberant 1930 Mille Miglia, when Tazio is supposed to have switched off the lights of his Alfa Romeo 1750 so that he could creep up on race leader Varzi and dash past him to win. Farina said, “Nuvolari went racing dressed like a Sixties beatnik. Varzi, on the other hand, was always elegant in a sort of ceremonial driving suit and he always wanted his car polished.

“It is difficult to imagine two more different people. Varzi seemed so reserved and Tazio the eternal boy. You should have seen Nuvolari with that courageous woman who was his wife, Carolina. They were like two happy schoolchildren.

Photo: Alfa Romeo

“It was always a spectacle when Varzi and Nuvolari were on the track, with their different driving styles: they were like night and day. Varzi manoeuvred the steering wheel as if it were a compass, Nuvolari as if it were a roulette wheel,” Farina said.

Ferrari’s double F1 world champion Alberto Ascari not only won the 1954 Mille Miglia for Lancia, but also the race’s first Nuvolari trophy, a gold tortoise that went to the fastest driver over the Mantua leg of the classic road race. Receiving his diminutive award, Alberto said, “I met Tazio way back, at the Grand Prix of Monza when Materassi, Brilli Peri, Borzacchini and Campari all competed in the Alfa P2 as did my father, the great Antonio Ascari, if you will permit me to say so. I was only a kid at the time, but on the eve of the Grand Prix, I was able to watch practice from Lesmo and study the style of the drivers, measuring their audacity. I loved the way they pushed themselves to the limit of the laws of physics.

“My idol at the time was, you’ve guessed it, my father. But one day, I noticed another man was greater than him: it was Tazio. And he had to be much better than all the others for a small boy to admit that anyone was better than his father. That tells you something,” Ascari grinned.

Photo: Alfa Romeo

In 1931, Luigi Arcangeli, who had competed against Nuvolari on motorcycles and cars, loaned Tazio his riding mechanic for that year’s Targa Florio. The person in question was a thin, pimple-faced youngster named Paride Mombelli, who was scared to death. Mombelli said after the event, “Mr. Nuvolari asked me if I was afraid of doing the race with him and he advised me to listen carefully to what he shouted every time he went into a difficult corner. When he shouted, I was supposed to throw myself under the dashboard to protect myself in case he rolled the car. The fact is, Nuvolari started shouting as he went into the first corner and never stopped until he came out of the last. I never saw anything of the race.”

Tazio’s favourite cousin, Milada Nuvolari, said of him, “He was always on the limit and the people adored him for that. He was even applauded when he lost a race and was able to perpetuate his legend even in defeat, because he always gave everything. Many tried to copy and explain his driving technique. Tazio brushed the kerbstones and came within a millimeter of the straw bales as regularly as clockwork. He was at one with the car: it seemed almost like he was pushing it with his arms and torso. He inserted his car into a corner like nobody else and exited from it faster than the others. He was always able to squeeze just that little bit more out of an engine. The car often broke, and sometimes he had an accident. But he once said to me, ‘Milada, as soon as I realize I can’t keep the car on the road anymore, I am always ready to jump out. Never stay in a car when it is about to crash.’ He was very agile.”

Friends off the track, Tazio Nuvolari and Achille Varzi were at each other’s throats on it. Early 20th-century Grand Prix and double Targa Florio winner, Felice Nazzaro, saw them like this: “Analyzing them singly, they had two different characters, systems and methods of driving that always led them to a victorious conclusion, when they did not experience mechanical or other trouble, of course.

Photo: Alfa Romeo

“Nuvolari was all fire and daring. He lavished maximum energy and immeasurable courage on every race. He tended towards one single objective: to be the dominator at the head of the pack, leading them all. His invincible battling spirit carried him up to an instant before the start of a race, then off he went on an unstoppable charge towards full and unconditional success.

“Varzi was a great driver, but less obviously so to the crowd. He impressed the experts with the truly superior style he demonstrated on the track. In the few races that I attended, unfortunately as a spectator, I found in Varzi such a wide range of stylish finesse and tactics that he really impressed me.”

Tazio’s trusted mechanic and long-time friend Decimo Compagnoni, who also came from Nuvolari’s hometown of Mantua, told a hair-raising story. He rode shotgun for the fearless little driver in the 1931 Circuit of the Three Provinces race, when Tazio beat a mildly successful racing driver and future legendary constructor named Enzo Ferrari.

“Tazio and I had the Alfa 1750 and we were competing against the 2300s of Ferrari and Borzacchini. We started from Mantua on the Sunday morning and, while all the others knew the route perfectly, Nuvolari had not even been able to practice a single kilometer of it.

“Off we went and, just outside a village called Porretta, we took a corner that was immediately followed by a railroad crossing. It was too late to brake. We slammed onto those infernal rails at 100 km/h and took off.

“The impact was so severe that I was catapulted into the air and even the grab handles I was hanging on to broke off.

“I fell back onto the tail of the speeding car, without anything to hold on to. I managed to hang on just long enough for Tazio to grab my leg and pull me back into the cockpit with one hand, while he had the other on the wheel, correcting the mad zigzag of a line he was taking.

“But it did not end there. The impact with the rails had broken the accelerator spring. So we stopped, I tore off one of my sock suspenders, fixed it to what was left of the spring and off we went. The suspender operated the accelerator, with me keeping it taut. It worked fine, but that did not change the fact that we were pushing the situation to the absolute limit.

“Going up a steep hill, I shouted, ‘This is where the 2300s will make us eat dust.’

“Going down the other side, it was Nuvolari’s turn. ‘This is where we’ll give them some dust to eat’. And we charged on.

“Borzacchini retired with an engine problem and that just left Ferrari up ahead. We were 40 seconds behind him when we were 36 kilometers from the finish, but in the end we won the race.”

In fact, Enzo Ferrari was to say later, “Tazio Nuvolari’s driving technique remained, until the end, that of an instinctive prodigy at the limit of human possibility,” an opinion shared by Ferdinand Porsche.

In 1937, after Tazio had been asked to drive for Auto Union, it was Porsche, the great designer and scientist, who told the directors of Auto Union. “I have never made a more appropriate choice in my life. He’s just the man we want to drive our cars.” And when Nuvolari arrived at the company’s Zwickau headquarters to be introduced to his teammates, Porsche told them, “Gentlemen, Nuvolari has joined us: the greatest driver of the past, the present and the future.”

Many years after Tazio died, his wife, Carolina, spoke of when her husband came home from the 1937 Vanderbilt Cup to Mantua after the death of their eldest son, 18-year-old Giorgio, “Tazio returned home and cried. It was the first time I had seen him cry like that. He forgot he was the fearless Nuvolari, the man who didn’t believe in danger or death.”

After that, Nuvolari focused all his affection on his younger son, Alberto, who would also die at 18 years old. Said Carolina, “Alberto became our only child. He had brown hair and the long, clean-cut face of the Nuvolaris. Tazio brought him home the most beautiful and expensive toys he could find on his trips. Pedal cars, rocking horses, huge boxes of Meccano, aeroplanes that actually flew. He came in with his arms loaded with parcels and went looking for Alberto.”

But Alberto once said to his mother, “I can’t stand it anymore. I look into Dad’s eyes and I see they are looking beyond me, searching for Giorgio.”

Nuvolari was supposed to have had a roving eye, and was certainly admired by women. One lady of noble birth wrote to a friend in the mid-’30s, “There are three men I admire most of all, Michelangelo, Mozart and Nuvolari.”

Stories abound of him kissing beautiful girls as he gave them unofficial rides in his racecars, gave presents to certain beautiful women and played the fool for the entertainment of others. But Carolina was convinced he was true to her. She said once, “Tazio was good, talented and never complained. The only thing that misunderstandings arose over was jealousy. He received attention, honors and invitations from all over the world. He was always surrounded by famous people and beautiful women. If I had not known my husband well, I would have gone mad. But I didn’t, because Tazio never left himself open to criticism.”

Photo: Alfa Romeo

Milada saw another side of Tazio Nuvolari. “Women? I must admit they were a passion of the Nuvolaris. I remember one time, after one of Tazio’s many victories, I went to say hello to him at his hotel. I went into his suite and was surprised to find it full of flowers. He understood my surprise. Just a look between the two of us was communication enough. I said I would see him later. I had recognized the woman who was with him, a very sophisticated person who was the wife of another driver. As I was leaving the hotel, I saw Tazio’s wife, Carolina, going in. She was not supposed to be there, but perhaps she wanted to surprise him. I ran back to his suite, but Tazio remained calm. ‘Wait here,’ he said. ‘As soon as Carolina arrives, tell her this lady is your friend and that the two of you have just dropped in to say hello.’”

Tazio was under no illusion as to his own worth. A VIP foreign journalist arrived in Sicily to cover the 1931 Targa Florio and asked the Flying Mantuan to give him a demonstration drive in his Alfa Romeo 1750 SS. Nuvolari bided his time until 2:00 AM one morning, when the telephone jangled in the writer’s room and a rather pompous concierge drawled, “Mr. Nuvolari and his Alfa Romeo await you, sir.” After frightening the life out of the journalist with an exceptionally fast drive in the dark, the quivering writer asked Tazio why he had chosen such an ungodly hour for the drive. “Sicily is infested with bandits. Think of the ransom they could demand by kidnapping the greatest racing driver in the world.”

Enzo Ferrari said of his gifted driver, “Even when Tazio moved to a foreign team, he never forgot he was Italian. I still remember today his yellow racing jerseys and, in particular, the ribbon in the Italian national colors around his neck, which he kept in place with his gold tortoise brooch.”

Although seriously ill, Nuvolari still decided to compete in the 1947 Mille Miglia in one of Piero Dusio’s Cisitalias. Fans and journalists alike were moved to tears at the sight of their sick hero battling it out for them again and one paper headed its story, “Thank you for this gesture, Tazio.” Even so, he nearly won the race, eventually coming in 2nd.

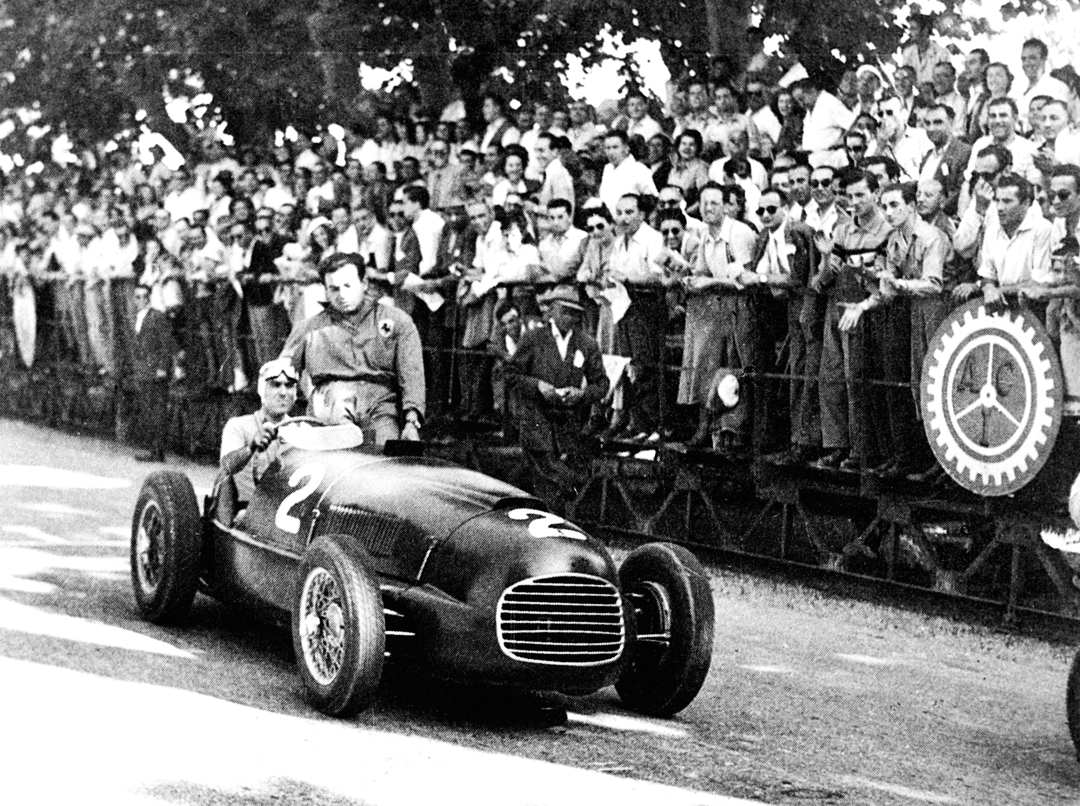

The ailing Mantuan immediately fell in love with a 2-liter barchetta, which Ferrari had built for the 1948 Mille Miglia, and the man from Maranello asked Nuvolari to drive it in the event. “Break the car,” Enzo said. “Break it. If you are not able to destroy it, no one will be able to pass you, not even the devil.”

The car broke, all right, and the devil did not bother. He could see that, although Tazio was putting in one of the greatest drives of his life, the Ferrari was, indeed, self-destructing. The last of a series of disasters put Nuvolari out of the race: a suspension stud went. And when the Flying Mantuan retired from the race, a nation wept for its terminally ill champion.

Photo: Ferrari

Vincenzo Florio, Sicilian motor racing pioneer, inventor and organizer of the great Targa Florio road race, remarked, “I must say that Tazio possessed an indisputable superiority over everyone else, because when he decided to overtake another competitor at all costs or to cover a stretch of road in a certain time, whether it was a straight or a series of tortuous corners, he put his foot down all the way and kept it there. He never lifted until he had achieved his objective. His arms and brain dominated men and things.

“I had never seen Nuvolari compete close up, I had only seen him drive by,” Florio continued, “until his last race, the 1950 Palermo-Monte Pelligrino. I must say that, apart from being astonished by a driving style that was all his own, I noted the slowing of his engine at every corner, although it was barely perceptible. The thing that struck me most was that in many corners, the front hub of his car was never more than a centimeter from the roadside wall.

“Nuvolari still holds the most amazing record for being the driver who had a non-stop, successful career throughout his sporting life: the record for having won the most races, and, finally, the exceptional record of having challenged danger for many years with extraordinary bravery and to have been able to end his glorious days in his own bed.”