The self-styled “Home of British Motorsport”, Silverstone, is one of the originals—it hosted the very first World Championship Grand Prix in 1950 and it remains a part of the series today, despite a near death experience in 2010 when the race was supposed to move to Donington Park. It is a truly fast circuit, or at least it was before the traditional “bent banana” layout became progressively more emasculated from 1991 onwards, and particularly post-Senna.

Surprisingly, however, Silverstone wasn’t that quick in 1950: in fact it was one of the slowest circuits of the era. The fastest lap in that 1950 GP was a mere 94.02 mph while Reims, Spa and Monza all saw laps at over 110 mph—Monza being quickest at 117.44.

Only Monaco was slower than Silverstone back then. Silverstone remained at the slow end until the 1970s by which time Reims had been consigned to history due to increasing road traffic, Monza was slowed by chicanes and Spa had been replaced by Zolder and Nivelles. By 1973, Silverstone had joined the big time. Laps at 134.06 mph in the Grand Prix and 135.96 in the International Trophy placed it among the fastest three tracks on the calendar.

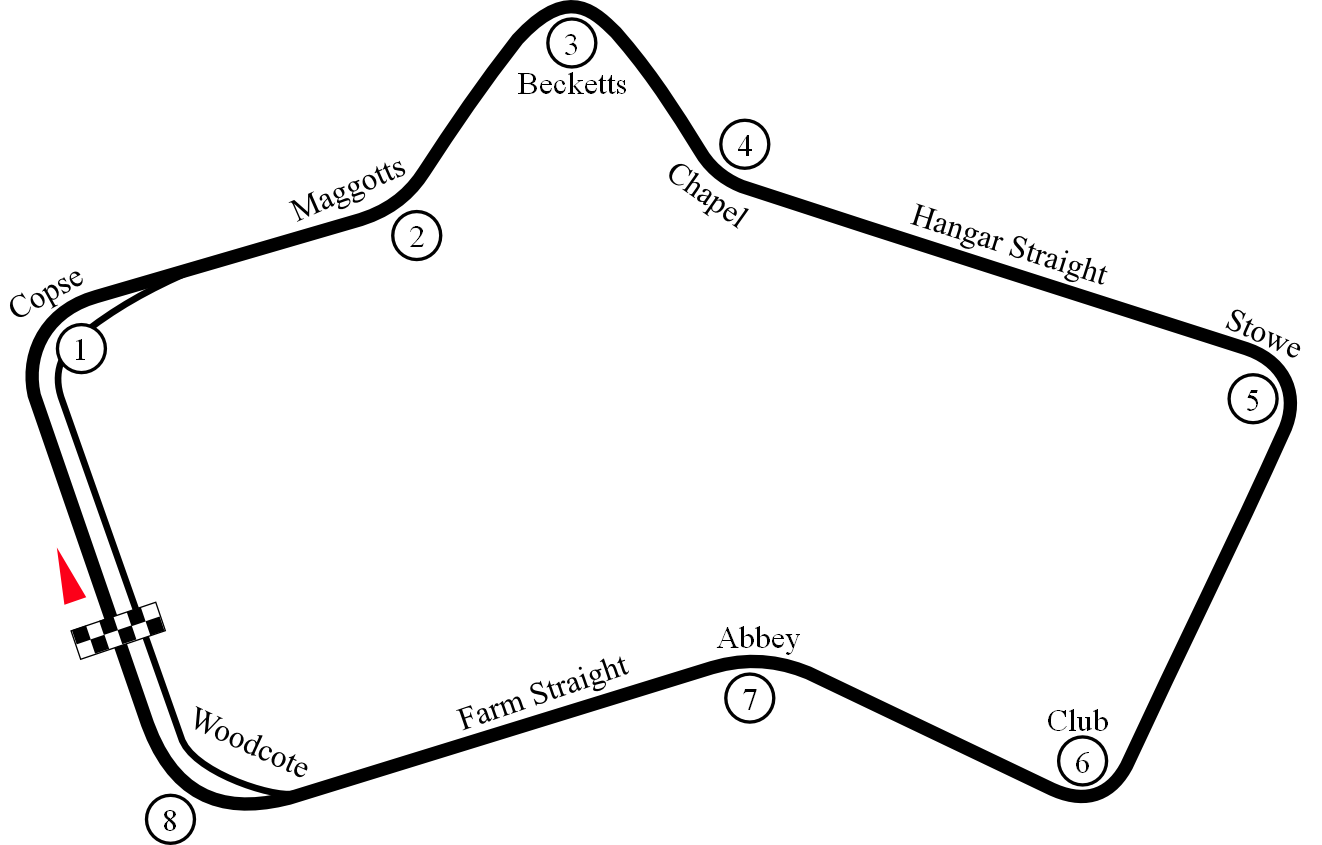

Silverstone had four fast to very fast corners – Copse, Stowe, Club and perhaps the most famous, Woodcote, it being the entry to the pit straight and the start/finish line. It was a devastatingly fast corner until, in 1975, Woodcote succumbed to a slowing chicane. Even so, just ten years later Keke Rosberg delivered a blistering 160.9 mph pole time at the wheel of a 1000-bhp Williams – Honda with full ground effects, the fastest lap ever on any Grand Prix circuit and a feat that remained unbeaten until 2004 at Monza.

Stowe corner then assumed the mantle of the quickest corner before it too succumbed to the inevitable demands for safety. Stowe was up there with Monza’s Curva Grande, Spa’s Masta Kink and the Gueux bypass on the post 1954 Reims circuit. In the 1950s, these were fast corners following long straight sections. They needed a good stab on the brakes before getting back on the loud pedal. In the 1960s and ’70s, such corners inspired less of a stab and more of a dab of brakes, then a confidence lift before turning in with the throttle nailed. Today’s Formula 1 cars would scarcely find them corners at all, such is the progress in aerodynamic performance and tire grip.

Like all great corners, Stowe has stories to tell— Mansell nailing Piquet in the 1987 GP and Stewart spinning off in the ’73 GP and disappearing into the high cornfields of Silverstone’s farm, to name but two. But I want to transport you back to 1967, the second year of the 3-liter formula, 12 months before aerodynamic appendages became de rigueur and a time when tires still had a tread pattern.

As was the tradition in the ’60s, one of the European season openers for the F1 boys was the Daily Express International Trophy. Silverstone was my home circuit – the place where I grew to love motor sport. I would persuade my father to take me, save to buy one roll of film for my Kodak Brownie and wander around the pits and grandstands enraptured. That year I decided to walk across the old infield section of the circuit along the central runways that formed the Second World War bomber base. At the crossover in the center, one could go left to Beckets, right to Stowe and further right to Club and Abbey. I picked Stowe.

The inside margins of Silverstone’s corners were then delineated by a low wall built of breeze blocks. Beautiful they weren’t, but they proved a very effective method of preventing corner cutting! I made my way to Stowe, right up to the inside wall, fully expecting to be given marching orders by the corner marshal. When I asked if I could take a few photos he replied, “Why not, we could do with some new blood at Stowe.”

OK the pictures from my camera were not going to give Louis Klemantaski sleepless nights, but I was as close as I would ever get to a racing car in anger…and I was overjoyed. Health and Safety – pah!!

Back in the 1960s there was no compunction for teams to turn up at F1 races. It was a matter of starting money and whether there were enough bits, or adequate funds, to repair the car after the last event… or, in Ferrari’s case, whether they were suffering a strike at Maranello or if they thought they could win or not. But it was always a special occasion when Ferrari turned up: then, as now, Ferrari lies at the very heart of F1 and a race without them was somehow never quite complete.

Despite the 1967 Silverstone race being but a week before the Monaco Grand Prix, Ferrari did indeed send a car for Michael Parkes. The Briton had been a Ferrari GT and sports car driver since 1961, but he was also a development engineer and tester for the Prancing Horse. Parkes made his F1 debut in 1966 after John Surtees left the team mid-season and he finished a respectable second at both Reims and Spa.

Because Parkes was a tall man, his 48-valve, 1966 chassis 312 was built with a long wheelbase and he had a strong record at fast circuits (witness his victories at Monza and Spa for the sports car team). Things were starting to turn out well for the man from Richmond on Thames, but at 35-years old this was not an opportunity to squander if he was to make a permanent mark on F1.

His opposition came from two works Brabhams, the car that won the 1966 World Championship, a BRM H16 in the hands of Jackie Stewart, a Lotus 33-BRM for Graham Hill, the delicious Formula 2-based McLaren –BRM for Bruce McLaren and Cooper-Maseratis for Bonnier, Siffert and Ligier and a few Lotus and BRM privateers. There were, however, no Eagles, no Honda, no Jim Clark and no second Ferrari: in fact only 12 cars raced since three new Pearce cars were burnt to a crisp in a paddock fire before practice began.

Practice itself was a furious battle between Parkes and Stewart who hurled the ungainly H16 round in 1 minute 27.8 seconds, the first official 120 mph lap of the Northamptonshire circuit. This time was subsequently equalled by Parkes and this duo was joined on the front row by Mike Spence and Denny Hulme some 1.4 seconds down.

The race followed the pattern of practice. Stewart and Parkes ran away from the rest of the field swapping the lead until the complicated BRM failed. Parkes stroked home 17 seconds ahead of a recovering Black Jack. Not a classic race then and not one that foretold the course of the 1967 season – Brabham went on to win four races and the driver’s (with Denny Hulme) and constructor’s titles, the fast but unreliable Lotus 49 also won four, while Cooper, Honda and Eagle scored solitary victories. Neither Ferrari nor BRM won a single Grand Prix, although Parkes went on to score a showpiece dead heat with teammate Scarfiotti at the non-championship Syracuse GP and a fifth place at Zandvoort before crashing on the first lap of the Belgian GP and sustaining injuries that ended his Grand Prix career.

Back to Stowe. The sight and sound of full-blooded Formula 1 cars in practice was astonishing. No driver trying for a time looked on rails or even fully in control, the cars understeering, oversteering and bucking towards the apex. It is evident from the pictures of Parkes and Stewart that they both were really “on it” and it made the difference that weekend. But the enthusiastic spectator had more than an F1 race to look forward to. The Grand Prix of today is all about F1and a homogenous package with a standard support of GP2 and Carrera Cup races. Not so in the 1960s.

In 1967, the support package was as eagerly awaited by the paying public as the main event. No fewer than 36 1-liter F3 screamers battled for 25 laps of the three-mile course headed by hill climb champion Peter Westbury. This was followed by another 25 lapper for sports cars – an entry of seven 250LM Ferraris and six Ford GT40s was as delectable then as it is today and David Piper’s BP green Ferrari led home Denny Hulme in Sid Taylor’s GT40. Then, as a warm up to the main event the ever popular 25-lapper for saloon cars took center stage, under the quaint sponsorship of Ovaltine, Britain’s night time milky sleep drink.

British saloon cars were no longer the warmed over showroom models of the late 1950s and early 1960s, it was outright war between Ford Falcon, Mustang and Chevrolet Camaro for overall victory, followed by Lotus Cortinas and the lone Porsche 911 of Vic Elford, then a phalanx of tire smoking Mini Cooper S models in the 1300-cc class and, in the sub-1-liter class, Ford Anglias and Hillman Imps.

Presenting a roll call of touring car greats the four classes were won by Frank Gardner in Alan Mann’s Falcon, “Quick Vic” in the 911, “Smoking” John Rhodes in a works Cooper S and John Fitzpatrick in a Broadspeed Anglia. Those of note who didn’t feature in the results included John Miles and Graham Hill in works Lotus Cortinas, Hill’s being an FVA-engined Mark 2, Jackie Oliver in a Mustang and Trevor Taylor in an Anglia.

The day was concluded by a 12-lapper for “Historic Racing cars.” From a field of 32 entrants a mere eight made it to the flag, headed by Peter Brewer’s 1959 F1 Aston Martin. His race time of 94.9 mph in an eight year old F1 car contrasts starkly with Parkes’ average of 114.65 mph, which in itself was only just over 4 mph quicker than Piper’s 250LM (110.17 mph). To complete the picture, the F3 race was won at 105.55 mph, while Gardner averaged 101.79 mph. It seems amazing today how close all the different categories were back then, even allowing for the fact that Parkes was never really pressed.

Happily there was no blood on the track at Stowe, or on any other corner that day. The blood was purely metaphorical.