Lotus founder Colin Chapman was undoubtedly gifted at what he did, admittedly some of his cars were better than others but in general, when Lotus built a racing car it was a good one.

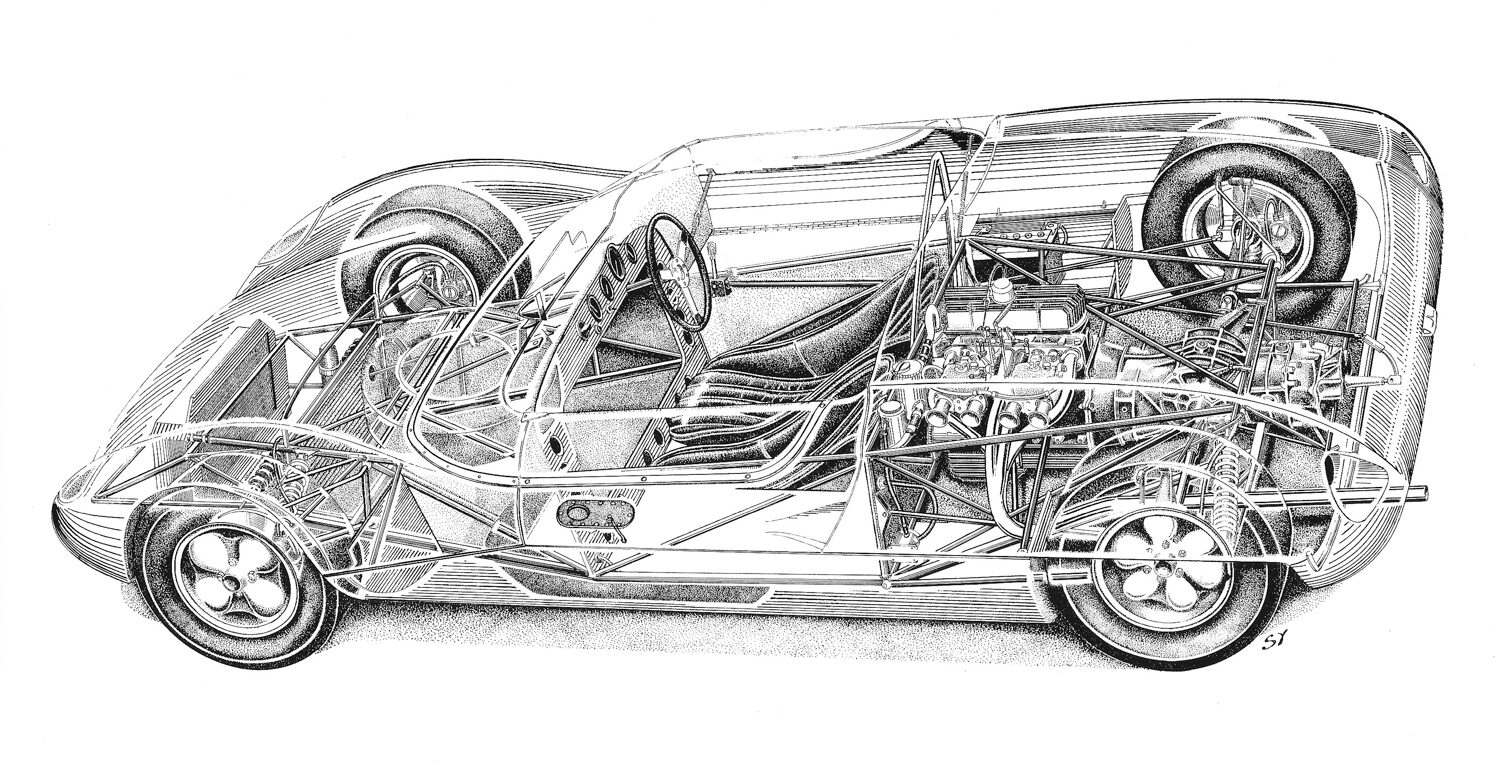

The Type 23 design was, in hindsight, one of the really good ones. Introduced at the UK racing car show in January 1962, the 23-sports racing car was based on a widened version of their existing Lotus Formula Junior chassis. These first 23s were fitted with a 4-speed transaxle and available with various engine options, including from under 1.0 liter up to 1500-cc, to allow its use in various capacity sports car classes of the time.

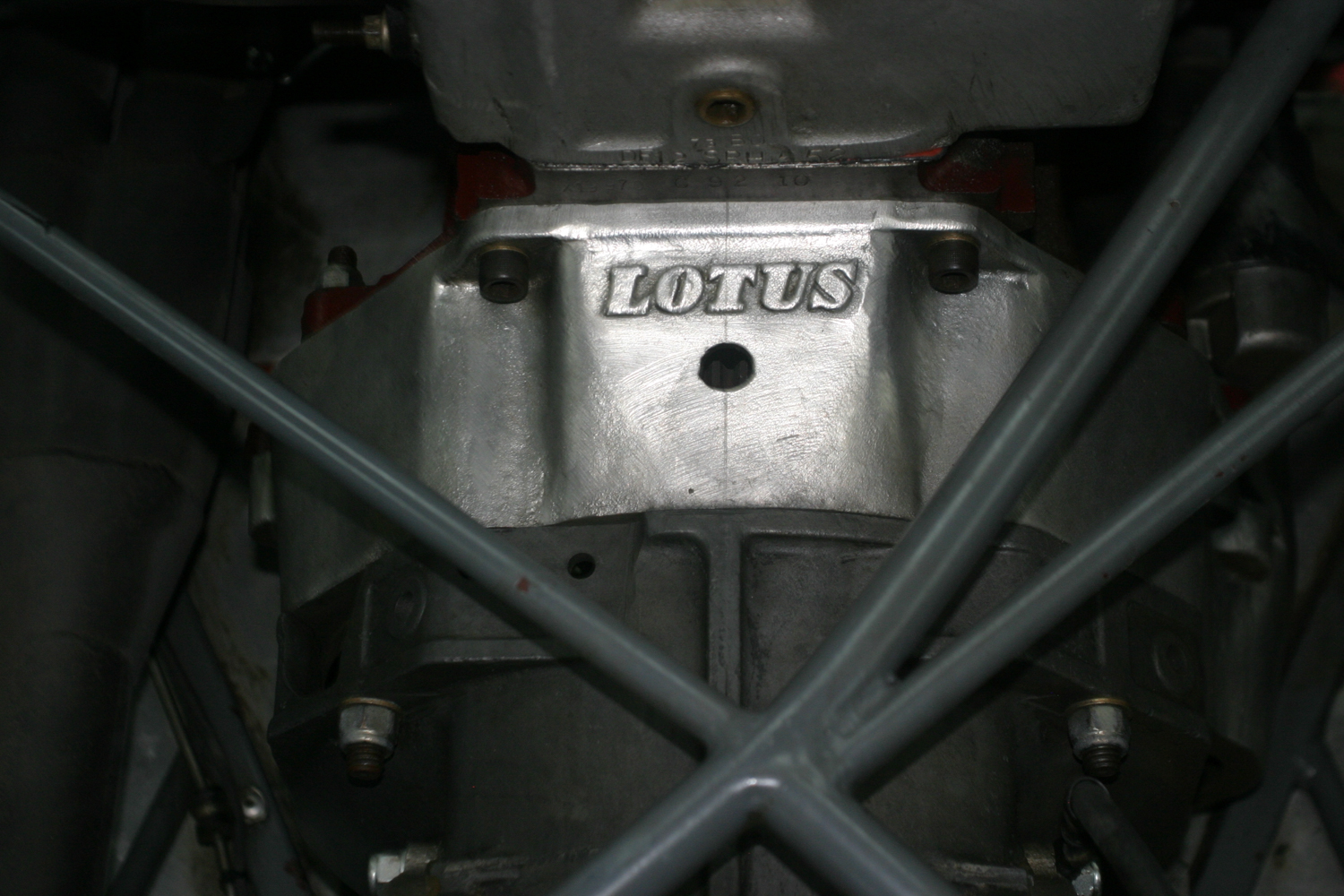

Chapman must have thought that his 23 lacked something though, because by 1963 the Lotus 23 had become the 23B when the design was updated with a strengthened chassis, 5-speed gearbox and most usually the Ford/Lotus twin-cam engine which by this time had grown from its initial (nominal) 1,500-cc to 1,557-cc which, with a 40 thousandth rebore conveniently came in just short of the 1600-cc class limit. In this form, the 23 was quite simply… blinding. Loads of additional power and not much more weight, very Lotus!

So, what is a 23C? Simply, it’s the 1966 developmental evolution of the 23B. The claimed reason for the updates was to allow the car to be more competitive against ever developing opposition and in typical Chapman style, getting more out of a four-year-old design meant clever thinking rather than expensive re-engineering, hence the mods are relatively few. Essentially, Lotus took the suspension, brakes and wheel/tire combinations from their Formula 2/3 cars of that year and fitted them to the 23B chassis. Visually, the cars changed too, as, to accommodate the wide rubber, flared arches were grafted on the 23B’s svelte glass-fiber bodywork.

While they might be simple, the updates work, not only does the revised suspension and far greater rubber area allow for much increased cornering speeds, the six-spoke wheels allow the new brakes to cool far more effectively as, while the magnesium wobbly-web wheels on the 23B look gorgeous, after a few laps you can’t touch the rims such is the amount of brake heat trapped by them.

Research points to there having been six factory 23Cs built (out of a total of 131 for all of the 23 variants), most if not all having been supplied to the USA, making them so rare that many of the often referred to books on Lotus fail to mention the 23C at all.

One must ask why Lotus didn’t build more of these ultimate 23s? It’s a difficult question to answer and was probably down to a combination of circumstances, reputation will have certainly played a part, you are only as good as your last design and their 1964 and ’65 sports racers, the big 30 and 40, hadn’t been successful. By ’66, the 23B was already 3-years old and things move fast in motor-racing, why buy a several year-old design when other manufacturers were lining up to compete in the prestigious sports car classes? Price would have played its part too, a 23C was listed at £2255 (export only) or £2205 in kit form for the UK market, their new (for 1967) type 47 racer only £400 more. Lastly, if the learned tomes are to be believed, Lotus wanted to concentrate on their single-seater aspirations.

Given that these should/would have been highly competitive in period, we have to ask why these are not better known? Well, according to the historians Lotus usually referred to the 23 type cars as series 1, 2 etc., rather than as 23/B/C, although they did use the 23B/23C nomenclature in some correspondence, for example the price list. Hence, in period events, they tended to be entered as just Lotus 23, after all it’s a racing car, why bother to record the series variant.

Now, some 55 years later, memory gets hazy and all the hard facts we can go on are those entry lists, unless they mentioned it was a 23C or we know for certain that driver ‘xyz’ was in a 23C at that event, from a bare list it’s near impossible to work out which variant it was.

The example we feature here, chassis 124, is owned by father and son, Tony and Charlie Best. Tony takes up the story:

“It appears that no cars were sold to the UK, and the entire 23C production went to Europe and the USA. It was in the States where I came across the car, cosseted in a private collection in the USA, running and pretty much as it was last raced. While many racers have been heavily updated throughout the years this one has escaped, it had been freshened up, but that was just paint, the rest is incredibly original for example, catch tanks, radiator etc. Indeed, all the fiddly bits that tend to be replaced over the years had escaped, even the bodywork is factory, the opportunity to buy it couldn’t be passed up. It’s taking a while to piece the history of this one together, what is for certain is that at one point it was fitted with a 1.1-liter fuel injected motor and Hewland MK7, 6-speed gearbox. When this was changed, we don’t know, but today this car runs a more conventional set up, the ubiquitous 1,600-cc Twin Cam coupled to a 5-speed Mk5 Hewland transaxle.

“An invitation to compete in the Whitsun trophy at the Goodwood Speedweek during 2020 meant a rebuild, this to close the gap between a car that was fine for the occasional on-track demonstration and something capable of running with the best historic sports racers in the world. The motor and gearbox were freshened up and received safety work such as crack testing and a modern specification roll over bar. In the Whitsun, the car showed its giant killing potential, running as high as 6th against such extreme horsepower weaponry as GT40s and McLaren M1As before an issue (later traced to be a fuel vaporization problem) knocked it out of the race. “

With another invitation to run at Goodwood in the diary, this time in the Gurney cup race at the 78th Member’s meeting, the early season has been about tweaks for both speed and reliability, the owner taking the opportunity to run the car in couple of the mid length Guards Trophy races organized by the UK based Historic Sports car club. The 23c now runs a 40-minute race without demur and the team are eager to see what lap time difference their tweaks have made when it’s run at Goodwood.

Driving Impressions

From the era where two seats actually meant two seats rather than a driver’s seat “cheated” towards the middle of the car leaving a passenger compartment that would barely accommodate a child, you sit very much to the right-hand side of the 23c. The first surprise is the gear lever, it’s on the right in single-seater style, with the linkage running down the side of the space frame. The first of the 23s did have their gear lever conventionally mounted in the middle of the car.

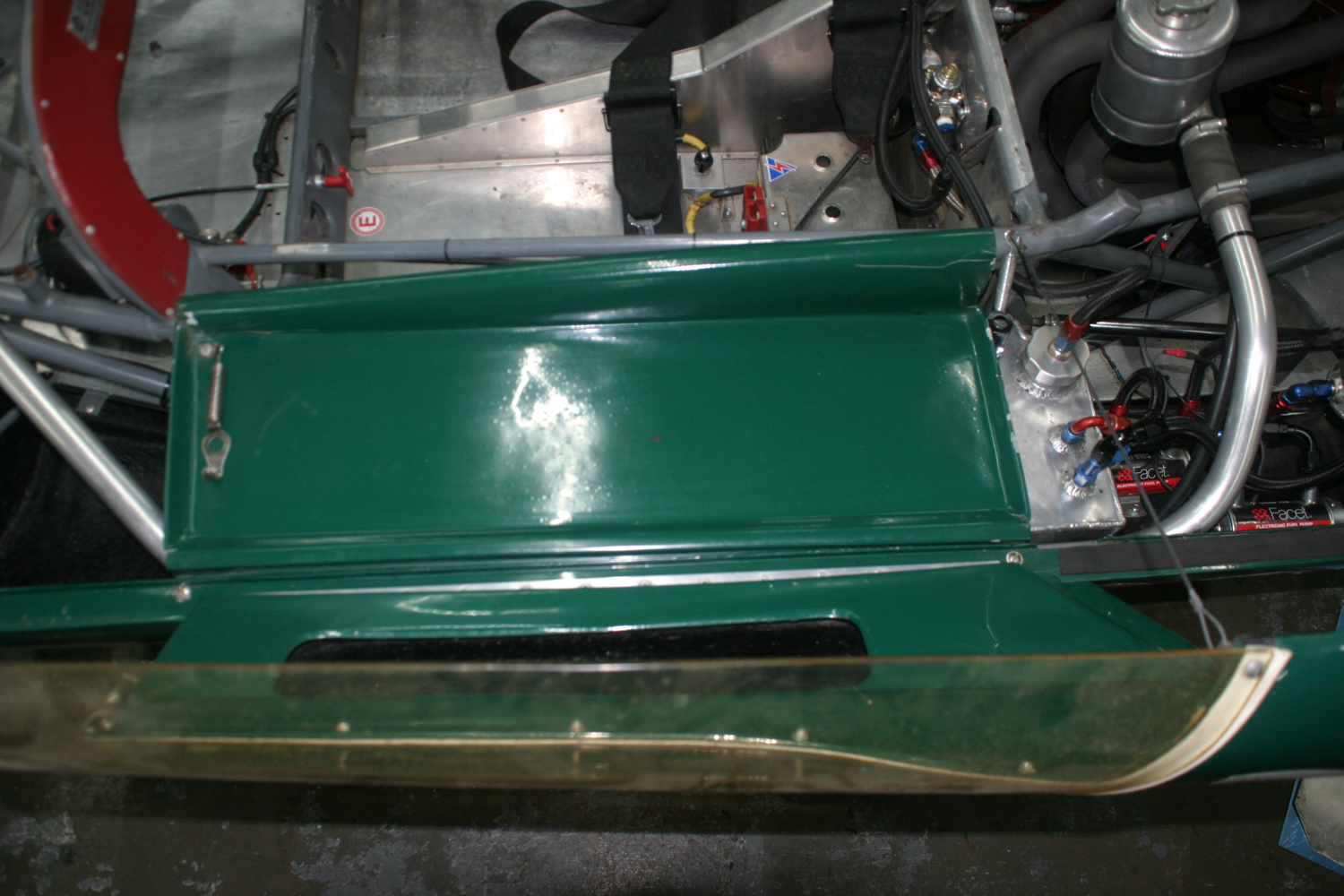

While Lotus did provide glass-fiber seats, indeed, the car came with two to facilitate the theoretical need to be able to carry a passenger, today, the left-hand floor is busy with fire extinguisher and associated safety equipment and there is a removable center divider to allow the use of a moulded seat to better fit the regular driver who’s a fraction taller than most.

Getting in it’s pointless opening the door as it flaps outwards and just makes it more awkward to step over the wide sill area, better to hop over it and stand in the seat before wriggling down the cockpit. While, for a minute or two it’s slightly odd having acres of space on your left, so far as legroom and general space goes it’s not much different to sitting in any single-seater of the period.

Although the 1598-cc motor is pushing out 175 bhp on its 45 DCOE Webers, by modern twin cam standards it’s tame, around 15 bhp short of the ultimate available from one of these. This relative lack of nervousness and the car’s overall light weight (Lotus optimistically claimed 7.9 cwt/885 lbs for the original 23!) means that it pulls away without demur, not quite road-car tame but neither does it need a zillion revs or for you to teeter on the knife edge between wheel-spinning out of the pit lane and a dead stall. First is the get you going gear, heavily sprung on a dog leg… left and back, while it can theoretically be used for hairpins, on most circuits it’s redundant, 2-3-4-5 being the usual race ratios.

While 175 bhp coupled with light weight makes it accelerative, you can’t expect Can-Am shove. By the end of the straight you are stepping on, but it hasn’t propelled you to the sort of speed where you may be tempted to back off a little early for fear of overshooting the braking point.

When you do hit the middle pedal, the brakes are reassuring and by the end of a session you’ll be taking it remarkably deep, especially as when you tip it into a corner, at the point where a 23b starts to drift on its narrow rubber, the C is still clinging on. Apexes are made with a degree of ease. The 23C will flatter an average driver and for most, reasonably quick lap times will come easily. Those times are helped by the less than nervous twin-cam which has (for a race motor), plenty of torque, thus offering an amount of flexibility should you drop a little below the power-band in those annoying between-ratio corners. Not that you do drop out of the power-band very often, it’s easy to keep the twin-cam spinning as the gearbox is a delight. As with most Hewland boxes, the fastest way to change up is clutch-less, ease the throttle and shoot the rifle bolt lever into the next cog, ready step on the power as soon as possible. Down, it’s heel and toe, with a dab at the clutch pedal for good measure.

There is, of course, a massive difference between reasonably, and very quick, while almost anybody can make it go fast, teasing the ultimate lap times out of it is a different matter. At the very edge, a combination of wide track and lots of tire means that the limit is exceeded quickly, it will snap at you if you tweak its tail too hard. Watch footage of a professional in this car and you’ll see that to get the very best out of it, the driver is very busy indeed. However, if you leave the hot-laps to the experts, and step back by a couple of seconds per tour, it stays utterly planted.

In period these little Lotus’ garnered a reputation as giant killers, notching up victories against cars of twice or more of their capacity. I put this to regular driver Ed Thurston, who chuckles… “It’s a giant killer for certain but its relative lack of power is frustrating in some races, for instance in the Whitsun Trophy I was around 250 bhp shy of the V8 opposition! I can drive around the outside of a GT40 in the corners, but once we reach the straight, they shoot off into the distance. Then, inevitably I’ll be back under their gearbox in the next twisty bit.”

That the Lotus is mighty in the corners is illustrated by its speed trap figures, while a GT 40 and the 23C have comparable lap times, at the end of the Hangar straight at Silverstone the 23C achieves 130 mph whereas the GT 40, has reached 158. The 23C is so competent and quick, it’s all too easy to forget how old they are, later mods aside they are essentially a 1962 car. A reminder of this comes when you are working on an on-track set-up, if you are after more front or rear end grip to dial out a balance problem or look for turn in/exit, the usual recourse would be a tweak on the anti-roll bars, but on the 23C they are fixed. Any tweaks to the settings are a case of damper adjustment and/or chassis rake, for a wet circuit, to tame a wayward rear end you can disengage the rear bar altogether, that’s as sophisticated as it gets.

The future? Tony and Charlie just want to take it racing, as they say, all the prep work has now been done, so let’s enjoy it.

Is the 23C the perfect historic racing car? Imagine the price tag for anything that is acceptable at the highest-level events, is unbelievably rare, definitely thoroughbred and from what some might to consider to be world’s greatest racecar manufacturer? Those credentials might cost you a million and further have the potential to chew through tens of thousands in prep-costs every year.

OK, a 23C won’t be yard sale cheap, but it won’t cost you a million either! Once you have invested in it, provided you are kind to the engine and gearbox it is about as low maintenance as you can get. You can’t quite throw it into the garage at the end of a meeting, then drag it out and top up the fuel when you arrive at the next event, but it’s close, I’d certainly be confident to run one on my average salary and know that I’d have some money left to be able to eat at the end of the month!

If that combination doesn’t make one of these near perfect as a historic race car, I don’t know what does.