1968 Austin-Healey Sprite Prototype

Many individuals and companies have an enviable record at Le Mans. However not many can match that of Donald Healey and his small, Warwickshire-based organization. From 1949 to 1970 there were a total of 28 cars entered in his name. This month we look at the last production-based vehicle, the prototype Austin-Healey Sprite that ran at Le Mans in 1967 and 1968.

Any form of professional motor racing is an expensive pastime. Running a single car at Le Mans would be just as prohibitive to most of us now as in the past and without any guarantee for success. Times have drastically changed, of course, as Le Mans has moved on from the days when it was seen by the English as a chance for some good sport against the “Frogs.” Le Mans today is serious business with multi-millions of dollars, pounds and Euros being spent to get a car across the line. Entrants are deadly serious today and would have been just as so in years past. Although you would like to think that it was all just that little more laidback in the years immediately following WWII.

Take the Donald Healey Motor Company (DHMC), for instance, established not long after the end of WWII with the intent of producing well-engineered sporting motor vehicles for the car-starved British motorist. After service as a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps during the Great War, Donald Healey started his own business servicing motor vehicles in his native Cornwall. His first shot at major motorsport was in a diminutive Triumph Super Seven in the 1929 British Rally. With his exploits turning to success, he was soon offered drives from such manufacturers as Riley, Triumph and Invicta. In 1931, he went on to win the Monte Carlo Rally in an Invicta 4-1/2-liter. Soon, he left his small business behind and went on to work for Riley, Triumph and Humber. Then at the end of WWII, at 47 years of age, he formed his own company in Warwick, England.

The first vehicles of the DHMC were bespoke motor vehicles and priced at the upper end of the market. However, Healey knew the value of competition and set out to promote the Healey marque through motorsport. In many ways it is hard to tell whether Donald Mitchell Healey was a shrewd businessman or a very keen motor racing enthusiast, as from the late 1940s through to the early 1970s it was rare not to see his name or his cars racing in the more important races throughout the world. In fact, Healey appeared to be more interested in motor racing than selling cars and perhaps saw the production of motor cars as a way to continue motor racing. Sound similar to other famous names in the world of historic racing cars? Very much so, as he has been likened to such great names as Enzo Ferrari and Colin Chapman.

First Le Mans Outing

Whatever Donald Healey was, he gathered around him a small group of fellow enthusiasts, all very keen on motorsport. The first production Healey car was built in 1946 with a special lightweight chassis, coachbuilt aluminium body, electron alloy front suspension and Riley drivetrain. It saw action in various events like the Alpine Rally and the Mille Miglia. However, it was Le Mans where the Healey was to leave its mark. During the 1940s and early 1950s, Le Mans was front-page news in European newspapers and especially in English broadsheets. In 1949, a lone Healey Elliot saloon ran at Le Mans, finishing 13th after completing 1,524 miles against 1,986 miles of the winning Ferrari 166MM. Hardly an auspicious success, but enough to inspire the small English manufacturer.

Then, as happens, fate lends a hand. Donald Healey, who had an interest in photography, while travelling to the U.S. by ship in 1949, met a keen photographer by the name of George Mason. Mason also happened to be the general manager of Nash Kelvinator and the meeting not only led to the Nash Healey sports car but to almost fairytale success at Le Mans. At the first attempt, a Nash-engined Healey driven by Duncan Hamilton and Tony Rolt came in 4th place overall. The following year the same team finished 6th. However, success was sweetest in 1952 when one of the two Nash Healeys entered finished 3rd behind two Mercedes, but in front of works cars from Ferrari, Cunningham, Talbot, Aston Martin and Jaguar.

In late 1952, the new Healey 100 became known as the Austin-Healey 100 and, as part of the deal, the DHMC was to have the responsibility of promoting the new marque through motor racing. Two Austin-Healeys ran at Le Mans in 1953 alongside a couple of Nash Healeys. In addition to Le Mans, the DHMC focused its attention towards Sebring and record breaking at Bonneville, in Utah. With the Austin-Healey released on to the burgeoning U.S. market, it was ever more important to gain racing exposure.

Despite the previous successes at Le Mans, the involvement of an Austin-Healey 100S in the tragic events of 1955 kept the DHMC from the French race for five years.

New Breed

The idea of the Austin-Healey Sprite was first conceived in 1956 during a meeting between Donald Healey and BMC’s Leonard Lord. They agreed that sports cars were becoming expensive and saw a need for an economical new breed of car not unlike some of the more sporting versions of the pre-war Austin 7. The idea was to produce a sports car using as many parts as possible from the BMC parts bin.

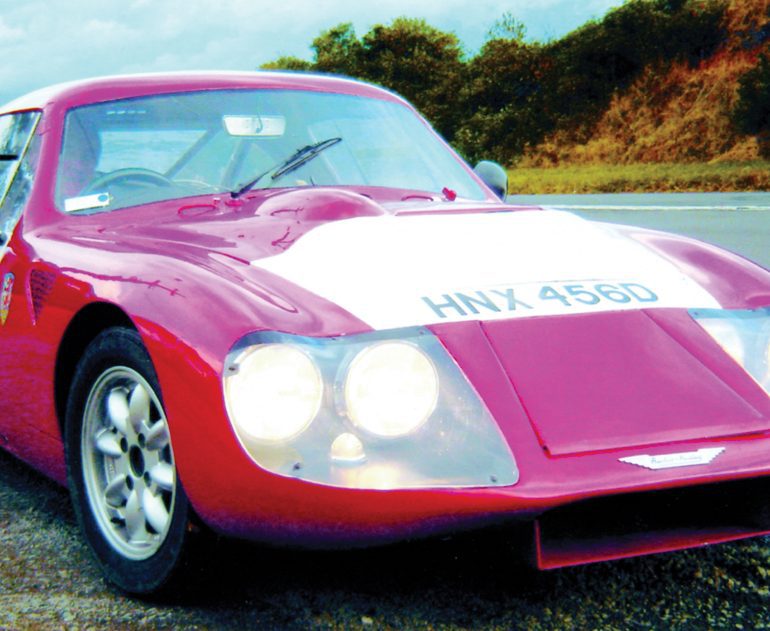

Photo: Patrick Quinn

Launched at the 1958 Monaco Grand Prix, the Sprite was well received by many testers, while some were less than complimentary about the Sprite’s cheerful frontal treatment. While the Sprite was built in Abingdon, the home of MG, it once again fell to the DHMC to promote it through motor racing. Competition success in events such as the Targa Florio, Sebring and Le Mans during the late 1950s and early 1960s would certainly earn coveted newspaper space in the weeks that followed. The first event was at Sebring in 1959, where the slightly modified Mk 1 Sprites managed 1st, 2nd and 3rd in class.

Sprites at Le Mans

While Sebring was certainly a focus for the U.S. market, the DHMC once again set their sights on Le Mans with entries in almost every running from 1960 to 1968, hoping for class wins. For the 1960 race, the Sprite ran under rules specifying that GT or production cars had to be at least 1,000-cc. Being 996-cc, the DHMC entered the car with a Falcon fiberglass body, which looked a little like a Birdcage Maserati. The little car performed admirably and completed more than 2,067 miles in the 24 hours to finish 16th.

The DHMC entered Sprites at Le Mans in 1961, 1963, 1964 and 1965, each car made in coupé form to provide for higher top speed along the long Mulsanne Straight. The 1965 cars were significant in that the coupé body was designed after extensive testing at the Austin wind tunnel. The Sprite floor-pan was significantly modified with the replacement of the steel floors and footwell panels by alloy, glued and riveted to retain strength. Other fittings included lightweight alloy Girling four-wheel dual circuit disc brakes, purpose cast magnesium Healey wheels and a full undertray.

The events leading up to the 1965 race were not without drama, with the cars arriving at the circuit painted in a fluorescent green. The Sprites were entered in the Prototype class and the officials from the Association Sportive de l’Automobile-Club de l’Ouest took one look at the cars, realized that the French cars of the same class were up against some stiff opposition, and insisted that the color be changed on the grounds of safety. After some consternation, especially from Australian driver Paul Hawkins, the Austin-Healey team, under Geoffrey Healey, relented. Luckily, a gallon of ex–U.S. Army WWII paint was found and the cars ran in the livery of drab olive green. One car, driven by Hawkins, finished a credible 12th overall and, as 1st in class, defeated all the French competitors in the same class.

Our Prototype

Again, in 1966, the DHMC entered two cars but both unfortunately didn’t last the distance. One of these cars carried the U.K. registration number HNX 456D. Over the following two years, the DHMC entered a single Sprite prototype, also registered HNX 456D, and this is the car that you see featured here. In 1967, the car developed 105 bhp breathing through a single Weber carburetor and was dry sumped. This proved to be enough to propel the car to 151 mph down the Mulsanne Straight with an average of 101.5 mph for the whole 24 hours! Its best lap was 108.13 mph, it travelled 2,422 miles in the 24 hours and finished in 15th position. It was the leading British car for the year, winning the Motor Trophy.

The next year the car developed 111.5 bhp, fitted with Lucas fuel injection and a cross flow cylinder head. This was enough for 154 mph down the straight, an average of 95 mph over the whole 24 hours; it travelled 2,126 miles and again finished 15th. Less distance than the previous year was travelled, as the organizers had installed the new Ford Chicane for 1968, slowing the whole race. That year the Healey team again won the Motor Trophy, as well as the Jaguar/Coventry Climax Trophy for the best performing British car. Additionally, DHMC experimental engineer Roger Menadue won Mechanic of the Year, having been with the DHMC since 1945.

Sprite Down Under

We could describe Joe Armour as the archetypal Austin-Healey enthusiast. Joe and Austin-Healeys go back to when he was a young bloke growing up in the inland town of Griffith in the Australian state of New South Wales and was an avid reader of contemporary magazines at the town library. Luckily, between Joe’s home and the library was the local BMC dealer and fresh on the showroom floor was a brand new Austin-Healey 100/6. Joe was bowled over by the car and its shape influenced his motor vehicle tastes for the rest of his life.

Joe finally got his drivers license and, like most of us, was busting to get his first car. He ended up having to choose between a Holden sedan with a single Weber, a Triumph TR3A and an Austin-Healey 100/6. Joe chose the 100/6 and had a ball with it. Over the years, a number of Austin-Healeys have passed through Joe’s hands and in 1976 he bought the works 3000 that ran at the 1965 Sebring 12 Hours.

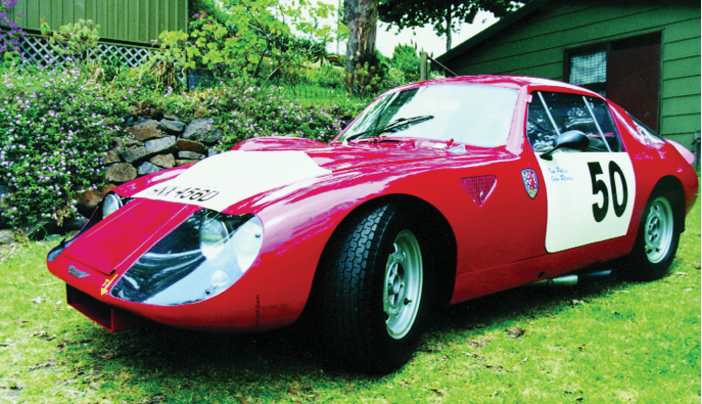

Photo: Patrick Quinn

“I first heard of the Le Mans Prototype Sprites over 20 years ago,” Joe told VRJ. “Australian Paul Hawkins had driven my 3000 at Sebring and also drove Prototype Sprites at Le Mans. I have become very interested in his career and the cars he drove. The 1968 race was the last time a Sprite Prototype ran at Le Mans and it was then displayed at the London Motor Show at Earls Court. It was then sold to Speed Sport Publications, the publisher of British magazine Cars and Car Conversions, for use as a promotional vehicle. After that it passed, via John Sprinzel, into the hands of Charles Dawkins, a strong member of the MG Car Club who had intentions of running it in the Targa Florio. However, as happens, plans were changed and it was sold again in 1975 to a keen motor racing fan, Ian Polley.

“Ian converted the car as it was run at Le Mans in 1967 with the single Weber dry sump engine and used it extensively in competition over the years. Besides circuit racing, Ian also raced it in the Brighton Speed Trials and hillclimbs. During his ownership the car was never rebuilt, just maintained in racing trim.”

First Sight

“Back in 1996 I managed to get to the International Healey Meeting in the U.K.,” Joe said. “That’s when I first saw the car and it rather surprised me that everyone was running about paying a great deal of attention to other cars and not to a light alloy ex DHMC racecar. I started talking to Ian Polley and found that we both shared a keen interest in the work of the DHMC and kept in touch since then. Some time after, I offered to buy the car and he said that I would have first refusal.

“True to his word, Ian called me at the beginning of 2000 and, after some lengthy phone calls, we agreed on a price. However there was one catch to the deal, one that I didn’t find much difficulty with. Ian said that the car, along with others from the Bentley Drivers Club, had been invited by Association Sportive de l’Automobile-Club de l’Ouest to take part in a historic parade before the 2000 Le Mans race.

“I thought it was quite fitting,” Joe added. “Then Ian suggested that I might like to attend and that was quite fitting as well. It was certainly an introduction to what was soon to be my car. We met at Brooklands for breakfast on the Thursday before Le Mans with the intention of following the route of the original Bentley team and arriving on Saturday morning.

“The cars in the convoy were just simply amazing. Long and short nose D-Types, Testa Rosa Ferrari, two GT40s, Aston Martin DB3, Talbot Lago, a couple of OSCAs, Ferrari 275GTB, Lancia Aurelia and, of course, a brace of Bentleys including No. 8 that had run at Le Mans. I remember sitting there thinking how very much over the top it was, like something out of ‘Boy’s Own Annual’.”

At Le Mans

“At Le Mans we were all ushered onto the track and parked on the grid,” Joe continued. “Each car was then introduced and all drove off for four high-speed laps of the whole circuit. My first real introduction at speed was sitting in the passenger seat watching the tachometer nudging 7,200 rpm in fifth gear, which would have been around 140+ mph. I think the top speed of the car certainly surprised quite a few of the others.

“Ian and I stayed at the circuit until about 3 AM the following morning just soaking up the atmosphere and visiting such significant corners as Indianapolis and Tetre Rouge. Le Mans is truly a most amazing race; it was wonderful to be there and especially to experience it in the Prototype Sprite.”

“I came back to Australia with plans to ship the car as soon as possible,” Joe said. “Then Ian called me to let me know that the car had received an invitation from Lord March to attend the Goodwood Revival. People are not invited, just the cars. By that stage the car was mine, but what could I do but agree? Ian then went ahead and arranged for John Rhodes, a Prototype Sprite driver from 1966 to drive the car at Goodwood.”

Arrived in Australia

Joe’s car ran at Goodwood and finally arrived in Australia in early 2001 along with a file of documents, spares and even signs from the 1968 London Motor Show. Like many enthusiasts, Joe has since further investigated the car’s early history. He was particularly interested in tracking down the link between the use of the British registration number HNX 456D in the 1966 Le Mans race as well as at Sebring of the same period.

Photo: Quinn Collection

Joe’s interest was really heightened when he chipped some paint from the rear of the hood opening, only to find it had at one stage been painted fluoro orange, the same color of the two Sprites that ran at Sebring in 1966. Then the investigation was on in earnest. Joe’s research was aided by copies of the long-defunct BMC publication, Safety Fast, that included articles by Peter Browning, who at the time was the competitions manager for the British company. It was a series of articles by Peter during 1967 that drew the earlier connection between the Le Mans entries and that for Sebring. Joe was also fortunate to discuss the car at length with Roger Menadue, who had prepared the DHMC competition cars. Of course, there are many publications with photos from the period to check, but the car’s earlier history was cemented when Joe bought a set of Sebring programs, result papers and race notes through eBay. Unbeknownst to Joe the seller was Ken Breslauer, the author of Sebring, The Official History of America’s Great Sports Car Race. Contained within the race notes were indications that the Sprite also ran at Sebring in 1966 and 1967.

So, after some fairly extensive research, Joe says the major race history of the car goes like this:

Year No. Drivers Place

Sebring 1966 66 Rauno Aaltonen & Clive Baker 2nd in class

Le Mans 1966 48 Clive Baker & John Rhodes DNF

Sebring 1967 59 Rauno Aaltonen & Clive Baker 1st in class

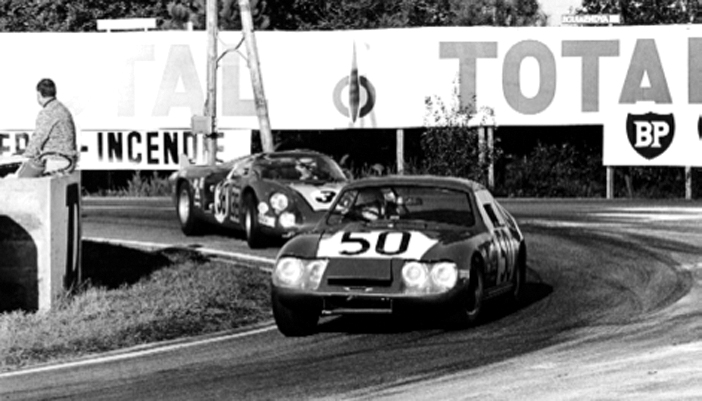

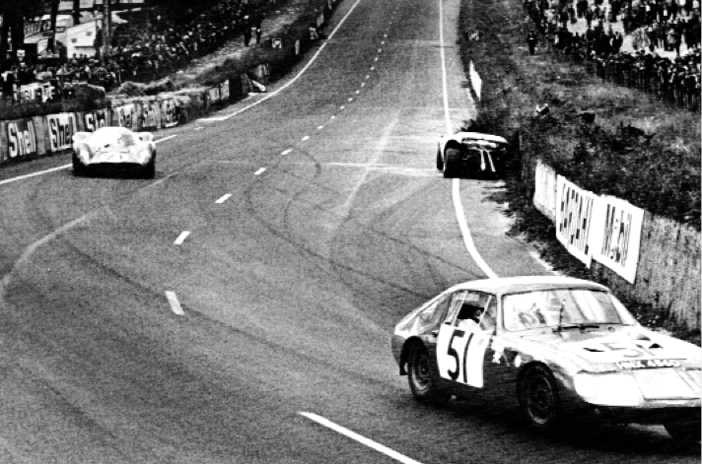

Le Mans 1967 51 Clive Baker & Andrew Hedges 15th overall

Le Mans 1968 50 Roger Enever & Alec Poole 15th overall

Interestingly, for its last outing at Le Mans the Sprite was known as a Healey Sprite, as Donald Healey had severed his connection with the British Motor Corporation in early 1968. The DHMC had also prepared a second Sprite for Le Mans that year but it was not used due to the loss of BMC sponsorship, and is thought to have been sold to Ship and Shore Motors in the U.S. They did, however, prepare and run a further prototype coupe called the Healey SR for the 1968 event with Coventry Climax V-8 power that expired during the event.

Driving a Prototype Sprite

Walking up to the Le Mans Sprite, it soon becomes very apparent how small the car is. With an overall length of just under 12-ft, it is certainly not the largest car in the world. However, for what it lacks in stature, it certainly makes up for in pure grunt. It’s not what I would call set up for comfortable touring either, but I suspect that I would happily live with that.

This is a little car with a big heart, as its size belies its performance. Moving it away from rest doesn’t require a zillion revs, but some deft treatment of the accelerator and clutch is needed, after that it’s just a matter of learning where all the gears are in the normal H-pattern shift. While accelerating, the chronometric tachometer jerks along its arc, but I am most particular that it doesn’t go past 4,000 rpm, as I live in fear of damaging something that isn’t mine. My self-imposed rev limit comes around in mere nano-seconds, then flick with the impossibly long gearstick. No crunch and onwards up to fifth, which is across to the right and up. Interestingly, there is a speedo for the passenger to look at—was this a Le Mans requirement?

Noise? Certainly, from a combination of straight cut gears, open exhaust and squealing brakes, but it isn’t unpleasant and is all part of enjoying such a car. How would I describe the handling? Shame there is no such word in the English language as chuckability. It is a most forgiving car that welcomes being thrown about and then immediately settles down, asking for more.

A fun car to drive! Too bloody right it is.

Living with a Prototype Sprite

Was Joe Armour mildly excited when his Sprite finally turned a wheel on Australian soil in early 2001? Does a kangaroo poo in the bush?

“I was pretty excited when it arrived,” Joe said. “I like to use my cars on the road, for ordinary things like running down the shop on a Friday night for fish and chips. The Sprite is still to be registered for our roads but its time will come.

“There have been a couple of competition events at circuits in and around Sydney where I have had a ball. Although, with the five-speed box, the car hasn’t been able to extend itself as the straights are nowhere as long as Le Mans. Driving the car with any enthusiasm, I get the impression that the engine will rev its head off, as it’s very easy to over-rev it. At one circuit it’s possible to get into fifth about 200 meters before the end of the straight, while it’s just a waste of time at some others. It’s still geared for Le Mans.

“I would describe the performance from the car as from a fast road Sprite. There is no doubt many sprint cars would be quicker but I don’t know if they could maintain the performance for 24 hours. Since the car has been in Australia, all I’ve had to do is just add fuel, however the Friday night fish-and-chip run might take a little longer with the car. It’s just not possible to get in and drive away. With the dry sump lubrication, proper warming up is crucial, as there are nine liters of oil to warm up before you go anywhere. That takes about 10 to 15 minutes of letting the engine idle at 2,000 rpm. I find the car very light, predictable and forgiving, plus it will rev and rev. The same engine fitted to Formula Junior cars will rev out to 10,000 rpm but, of course, is far more highly tuned. While the Sprite has been mechanically rebuilt a number of times since Le Mans, the body and interior are as they were in 1968.

“Roger Menadue, who died a few years back, told me a little story about what happened directly after Le Mans in 1968. He was very keen on the Sprite winning the first British car trophy but there were rumors getting about that it was going to go to the race-victorious Ford GT40. He was incensed, asking why the Ford should get the award with its American engine. He was so fired up and about to storm off to tell the race organizers what for, but Donald Healey, who was also one of his dearest friends, calmed him down and convinced him to return to the U.K. Both Donald and Geoff Healey stayed at the circuit for the post race festivities and received the trophy on behalf of Roger. On their return to Warwick, Donald Healey placed the trophy on Roger’s desk, smiled as Roger’s jaw dropped and walked away without saying a word.”

Specifications

Chassis: Sprite floor-pan and riveted alloy sub-frames.

Body: All alloy two-seater coupe bodywork.

Wheelbase: 6ft 8inch

Weight: 1,498 lbs.

Suspension: Front: Independent with coils, Armstrong single-arm shock absorbers and anti-roll bar. Rear: Semi-elliptic springs, adjustable lever-arm Armstrong shock absorbers, as well as tele-scopic shock absorbers and trailing arms.

Steering Gear: Rack and pinion.

Engine: Four-cylinder, 1,293cc (71.12mm x 81.28mm)

Power: 111.5 bhp at 7,000 rpm

Carburetor: Lucas fuel injection (Le Mans 1968)

Clutch: Single dry plate.

Gearbox: Modified MGB gearbox and unique five-speed extension.

Gears: Five forward, one reverse

Foot Brake: Four-wheel Girling single-pot discs (dual circuit).

Hand Brake: Operating on all four discs.

Wheels: Cast magnesium Healey wheels.

Tires: 5.25 x 13 Dunlop racing (Le Mans 1968)

Resources

Chevalier, Herve. Les Healey au Mans 1949–1970. Hecom, 1998, ISBN 2-913117-00-7

Healey, Geoffrey. More Healeys. Haynes Publishing Group, 1980. ISBN 0-85429-826-6

Laban, Brian. Le Mans 24 Hours. Virgin Books, ISBN 1-85227-971-0