1934 Riley Nine MPH Le Mans Special

If not the dream of everyone with any interest in motor racing, it must be at least a part-time fantasy of every male who has ever seen an automobile. (I leave females out here as I believe they are less prone to this sort of fantasy life!)

Through the magic first of live television and on-board video cameras, and now via You-Tube, everyone can have a taste of what it is like to be in a Le Mans racer of almost any vintage, and feel the thrill of the Mulsanne Straight or the immensely fast piece of road from Mulsanne Corner to Indianapolis. Derek Bell gave thousands a ride in his Porsche 956 at the Nürburgring and Le Mans, and many have become hooked on the experience. Even professional drivers have taken up simulations of all types to learn their way around circuits, including some current Grand Prix pilots.

Photo: Peter Collins

As exciting and addictive as that may be, however, the quintessential reality of racing can never be simulated. Some of the contemporary racing games are coming pretty close, I admit, but the wind is never in your hair or eyes or the smell and heat in your nose when you sit in front of your computer.

As it turned out, the fantasy of propelling a Porsche 917 through the night at more than 200 mph didn’t come close to the reality of actually driving a car capable of only half that speed. Through the generosity of car owner John Ruston, I was having my second attempt at the Le Mans Classic. After a short run in his Chevron B8-BMW in 2006, I was back, this time in the very car that finished 2nd overall in 1934, and won its class—the Riley MPH Le Mans Special. The reality was indeed much more interesting than the fantasy.

Riley…a long history

Photo: Peter Collins

The Riley company does not quite go back to the dawn of motoring, which arguably started in 1885 when Benz built his first automobile. During that period the Riley family of Coventry were master weavers and builders of weaving equipment. When William Riley sensed that the weaving industry was about to go into decline, he purchased an existing, small cycle manufacturing company in 1890 and by 1896 this had become the Riley Cycle Company Ltd. In 1896 a powered Riley cycle first appeared. Riley’s four sons, Victor, Stanley, Allan and Percy, were involved in the company and Percy designed and built a prototype motor car that didn’t go into production. However, powered tricycles and quadricycles did.

As the Riley Engine Company was established, production flourished and Riley built a reputation for variety and flexibility. This became the Riley Motor Manufacturing Company after WWI, and then Midland Motor Bodies Ltd. Riley became prolific manufacturers, and in the early 1920s was producing as many as 20 different models, often bringing one of each new model to a very large stand at the London Motor Show in the period. The first “proper” Riley car, the 1905 9 HP machine, was the first car anywhere to standardize detachable road wheels. The company also pioneered the development of quiet engines and strong, reliable gearboxes.

Photo: Peter Collins

While Percy Riley was generally not in favour of motor sport, customers began running Rileys in speed trials and hillclimbs as early as 1906, and Victor Riley himself competed successfully in his 9 HP, beating many bigger machines over the flying kilometer. By 1926 the basic 4-cylinder 9 HP was known as the Riley Nine, while a 12 HP side-valve engine also appeared. In 1927 a Riley Nine was much modified and turned into a true competition car, and was known as the Brooklands prototype. Monaco and San Remo bodies were appearing on Rileys and the connection with motorsport and European glamour was gaining prominence. Over the next few years, the Brooklands Nine became very popular in British racing. Into the 1930s, popularity of the make spread far and wide. A 6-cylinder engine had joined the 4-cylinder, and both Brooklands models and race-prepared touring Rileys built up an impressive list of race and rally results, including the Monte Carlo Rally.

In 1932, this Riley 6-cylinder was reduced in capacity from 1633 to 1486-cc in order to compete in the 1500-cc class of events worldwide. This engine featured triple side-draft carburettors and a number of other mechanical advances. The engine powered the new Brooklands Six and this car started to build up an impressive record, especially at the Brooklands track after which it had been named. Throughout this period Riley continued to produce a very wide range of vehicles from sporting two-seaters through luxury saloons. The rapid Freddie Dixon did a great deal to enhance the car’s reputation with his many racing successes…he was a hero of the time.

Photo: Peter Collins

The M.P.H.

In 1934, during the heyday of the Riley company, the new rally-oriented Imp made its debut at the Scottish Rally, which also marked the appearance of yet another Riley two-seater, a largely experimental model called the M.P.H. This was essentially the 6-cylinder version of the 4-cylinder Imp. The M.P.H. came with a choice of two engines and gearboxes, a 1458-cc unit with either a close-ratio Silent Third box, as the Riley unit was known, or the Wilson “Preselecta,” and a 1633-cc engine with the same gearbox choice.

Only 20 M.P.H. models were built, and two of these were known as the M.P.H. Specials. They were also variously described as 12/6s, or even 6/12s by Le Mans organizers or as the Riley 12/6 M.P.H. Racing model, and even as the Riley Nine M.P.H. Racing, thus ensuring confusion among historians forever more.

Le Mans was the highlight of the 1934 season for Riley, and the entry included three Ulster Imps, a Brooklands 9, and the two M.P.H. cars. The Ulster Imps had slightly modified Imp bodies. The opposition came mainly from four Alfa Romeos and several Bugattis, and the rest of the field all had smaller engines. The two M.P.H. cars were to be driven by the renowned Freddie Dixon and Cyril Paul, and by two French drivers, Jean Sebilleau and Georges Delaroche. The Alfas were in the hands of real star drivers, Philippe Etancelin/Luigi Chinetti, Earl Howe/Tim Rose-Richards, Raymond Sommer/Emile Felix, and Clifford/Saunders-Davies. Alfa had won the three previous 24 Hours, and Sommer, Chinetti and Howe had all won before.

Photo: BMIHT

The Riley fortunes did not look bright in the early hours, with one car off the road for a while, and others making a number of stops. Freddie Dixon ran highest in the order in 8th, behind two Bugattis, four Alfas and an MG Magnette. As it got dark, Lord Howe’s Alfa led and Dixon was 6th, but as dawn appeared, the Dixon/Paul 6-cylinder M.P.H. and “our car,” the Sebilleau/ Delaroche M.P.H., were fighting for an amazing 2nd overall. By midday, Sebilleau had moved past Dixon, so that Rileys were 2nd, 3rd and 4th, and all the Rileys were well placed and intact. At the finish, Riley made history by becoming the first marque ever to have all of its cars finish—six started and six finished. Sebilleau and Delaroche were an amazing 2nd overall behind the Etancelin/Chinetti Alfa 8C, winning the 1100-1500-cc class from Dixon and Paul while averaging just over 70 mph.

Riley continued to diversify over the next few years, an action that helped to account for its downfall. By 1938, the company was in trouble, demand was down, costs were up, and Riley went into receivership. It was taken over by Lord Nuffield and became part of Morris Motors. A Riley model continued for many years, but 40 years after the first car had appeared, there was no longer a Riley Cars Ltd.

Photo: ACO

Driving at Le Mans

Only two of the special racing Riley M.P.H. cars were built and these were made for the 1934 international season. Taking 1st and 2nd in class was a good reward for the effort, especially as KV9477 was 2nd overall. The cars were then run in the Tourist Trophy at Ards, but retired with a variety of ailments after being well up the order. It also seems possible that “our car” had competed in the 1934 Monte Carlo Rallye earlier in the season, although this is difficult to confirm.

After the 1934 Le Mans race, Riley built two new chassis frames for 1935, and these became known as the TT Sprites. They were fitted with the engines from the two Le Mans cars, along with their special competition gearboxes, and were entered at Le Mans in 1935. The new chassis had more compact bodies, and smaller Girling brakes. The 1934 bodies were put aside and presumably scrapped. When the competition department finally closed down at the end of the decade, Claude Wagstaff obtained a large quantity of spares, including the two 1500-cc Le Mans engines from 1934, their original gearboxes, the exhaust manifolds, oil tanks, competition road springs, and numerous other parts. All these parts were later acquired, in the mid 1990s by Nick Jarvis Sr. and Jr., well known vintage coach builders.

Photo: ACO

The components of the 3rd-placed Dixon car were sold to Phillip Hill by Jarvis, who then undertook rebuilding KV9477. Nick Sr. and Jr., between them, built up two M.P.H. Racing chassis and two bodies. The parts that were missing included 15½-inch magnesium brake drums, brake shoes, carriers and brake cams, and the magnesium rear axle nosepiece, among others. These were all made from scratch to original specifications, as the Jarvis family were very long time Riley experts and enthusiasts. They also made the unique front axle anti wind-up arms, which don’t seem to have appeared on other cars.

The original engine for “our car” was rebuilt by Keith Taylor Engineering in Yorkshire, and that included the fitting of a new EN40 B crankshaft by Doug Kiddy Engineering, and new con rods by Arrow. Ian Poulson, who figures large in this story as he was looking after the car at the Le Mans Classic, was responsible for painting the chassis frame, body, and wings. He completed the rebuild for John Ruston who bought it from Jarvis in 2007, and race prepared it for the Classic.

Pre-war at Le Mans

Photo: ACO

The atmosphere at Le Mans is always unique, whether you are stopping by for a quick look on holiday, coming to see the 24 Hours “main event” or spectating at what has become one of the most popular historic car events, the Le Mans Classic. I first stood in the pit lane back in 1968, when there was no barrier between the cars and the crew. Now I was, for the first time, sitting behind the wheel of a pre-war car here, the car with which Sebilleau and Delaroche fought their way into 2nd place in 1934.

John Ruston was doing his usual popular thing of bringing several cars to the Classic and overseeing the complex task of having cars in most of the six categories or grids or plateau. These plateau are for pre-war, 1949-56, 1957-61, 1962-65, 1966-72, and 1973-79 cars, and the very best from all these years now show up for this event. Each plateau has three 45-minute races during the 24-hour period, so cars are indeed running almost all the time. The Riley had four drivers assigned to it: Barry Cannell, Adrian van der Kroft, Margaret Diffey and myself. Adrian changed cars after one practice session and Barry went off to other things, so the M.P.H. was left to “Mags” and I. She is the widow of the great James Diffey, and it was a real pleasure being teamed up with her.

Photo: BMIHT

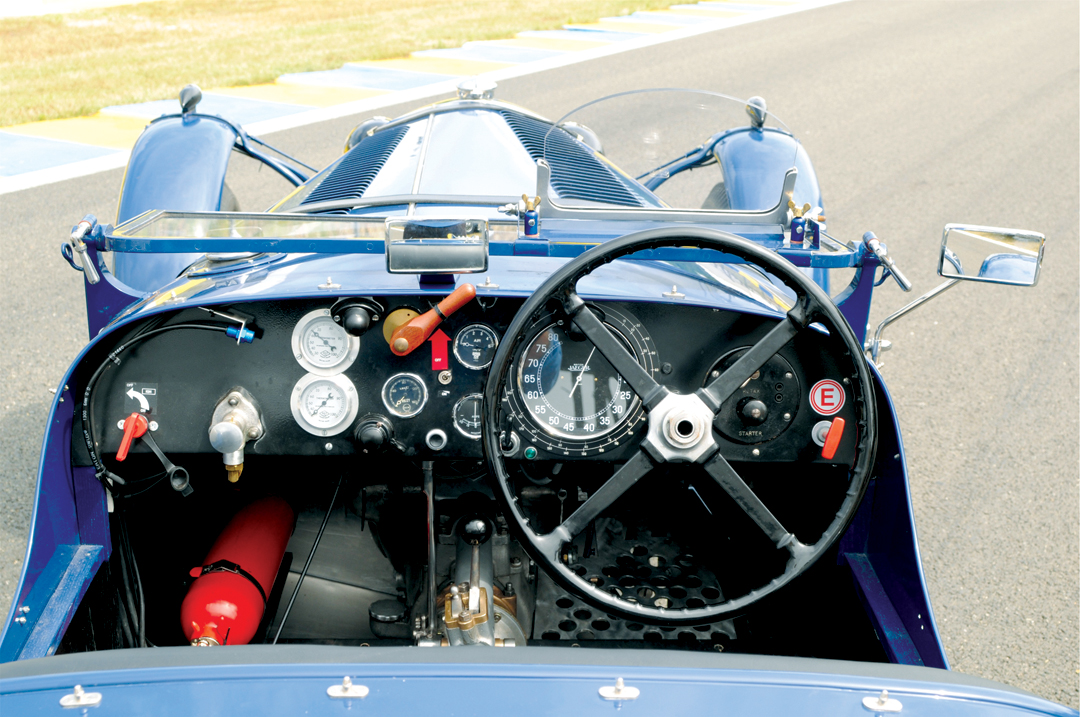

So, on a very warm and pleasant afternoon, I found myself in the pit lane waiting for practice, ensconced behind the large, four-spoke bakelite steering wheel that you sit quite close to. A large Jaeger rev-counter sits directly behind the wheel, reading up to 8000 rpm, and is flanked by outer dials that indicate both mph and kph in the various gears. This, of course, allows you to set a regular pace through a long endurance race, and gives an idea of how much faster people going past are! The small Riley dash is full of gauges for oil and water temperature, oil pressure, amperage, with the Rotax starter on the right. The oil pump needs to be primed before starting from cold. The original wooden handle for hand-priming the oil pump is still there, with light switches to the side. The interior is nice, comfortable old leather, and the seat pulls out to get to the fuel pump and battery. There is drilling in the driver’s side for lightness, the pedals are close together, and if you want to, you can look down and see the Mulsanne Straight passing beneath you! We were running with the aero windscreen rather than the full-width screen for “aerodynamic advantage,” and with a single outside mirror on the right and the central interior mirror, which meant visibility was good at all times.

The instructions for looking after the car were straight-forward: keep to about 5000 rpm (in spite of what the rev counter said!); don’t go below 2500 or the plugs may oil; and treat the clutch with care. The car was running on 5.00 x 19 Dunlop Racing tires on the front and rear. “Mags” did a few laps in the first Friday practice, followed by my own single lap to get it sorted, and then Adrian, who stopped with fuel starvation, and when it came in the plugs were well oiled. Some work was done on the rather daunting looking carburettor setup before the evening practice session. The heavy steering had caught me out at the chicane going up to where the Dunlop Bridge used to be. While the car may look light, it required some firm handling so that it didn’t get away! Through the quicker corners it was superb with no lifting, and the 6-cylinder engine pulled well, helping it to hang onto some of the much bigger machinery at least until they got their momentum back. The Le Mans chicanes, Mulsanne Corner, and Arnage tended to test the shoulder strength, so a bit of sliding and opposite lock through these tighter bends made the process a bit easier.

Photo: BMIHT

Drama ensued when it came to night practice, as Ian Poulson’s son John was sent out to check that the carbs were right. He only got to the top of the hill after the start and the clutch pedal seized on the shaft, so that meant no night-time practice. The six SU carburettors were then thoroughly overhauled and we all pitched in to free the clutch. We had managed a time that left us 53rd of 63 entries in the pre-war group, ahead of a Bentley, two Bugattis, two other Rileys and the amazing little Simca 8 of Evelyne Heise and former Grand Prix racer and Le Mans winner Jean-Pierre Jaussaud, one of the nicest guys in racing. The Simca changed four engines, countless gearboxes and most other parts during the weekend!

The race

When it came near race time, John Ruston announced that the Riley would be handled by “Mags” and myself, and the only team order was to make sure it finished all three races. “Mags” duly took the start of the weekend’s first race, which included a demonstration Le Mans start. Though this was a 45-minute event, our lap times at nine minutes were half again as slow as the fastest car, which happened to be our teammate, Gareth Burnett, sharing a Talbot 105 with Julian Bronson, turning in six-minute laps and being 13 seconds quicker than the 4.5-liter Bentley. “Mags” did the whole of the first race, including the mandatory stop, moving up from 53rd to 41st. Burnett and Bronson won that race in the Talbot by nearly a minute.

Photo: Maxted-Page

All this meant that I would now be racing the Riley after only one practice lap, with my co-driver doing the start and the first few laps. However, she came flying into the pit-lane after only one flying lap, worried that the engine wasn’t pulling properly, and we suspected the carburettors needed some more tuning. The pressure was now on…a bit…to get the hang of this well-known car and bring it to the finish. Fortunately, the Riley is very forgiving and perhaps not so quick that you will rapidly get into trouble. There is an immense sense of exhilaration heading down the Le Mans pit-lane at 1:00 a.m. and pointing that old nose into the darkness. The gearbox on the car was not the original “Preselecta,” having a more orthodox 4-speed, which behaved itself quite well. Keeping the focus on sliding through the corners meant we could avoid going down to second gear, and it also meant the driving was great fun. Somewhat to my surprise, I was now turning laps quicker than we had done in practice, and was starting to overtake cars. Poor John Poulson’s own Riley Sprite had stopped and the M.P.H. caught the Boucheron Bentley 4.5, the two little BNCs, the Cousseau 3-liter Bentley, another Riley Sprite, and then the two Bugattis, a Type 35 and a Type 44.

As if 1934 had come back, and Sebilleau and Delaroche were pressing on through the night, the Riley M.P.H. hauling in the big cars on the corners with better braking and handling. On the 4th or 5th lap a marshal with a large “Securite’banner on his jacket was standing on the edge of the track at Arnage. I remembered that our host at a local B & B was a security officer, and there he was, waving with a huge smile on his face!

At one point teammate Burnett boomed past in the Talbot. Gareth and Julian Bronson were sharing two Talbots, so they managed to both finish 1st and 2nd in that race. After our early stop, we came back to finish 40th. One of the Riley Brooklands had managed 32nd so the old Riley Le Mans tradition was intact.

Driving this wonderful old car under the stars on this most famous of circuits is a very emotive experience. There seemed no distance to the past as the car was once again where it belonged. The 6-cylinder barked sharply through the night, taking the Porsche Curves flat, sliding onto the pit straight and speeding in third and fourth past the still full grandstands, only going down to second for the Dunlop chicane and heading off again through the Esses and onto the Mulsanne. It hardly gets any better, and in the dark you can just concentrate on what the car is doing and get the most out of it. Down to third for the chicane on the straight, up to fourth, down to third again for the second chicane, up to fourth and on each lap trying to get through Mulsanne Corner quicker in third. This is a tricky corner that tightens up and catches people out. The sparking, flaming, smoky Lagonda V-12 of Klaus Lehr moved over so I could sling the Riley down the inside and aim for Indianapolis. You don’t get that on a simulator!

The only real problems with the Riley came in our third and final race early on Sunday morning. I was starting this time, the early morning sun requiring a change from goggles to sunglasses! The whole atmosphere was quite relaxed by now. Hence, the rule that racing didn’t start until the field passed the pits was rather abused and by the time I came round everyone was gone. That did provide the incentive to get the most out of the Riley, but also prompted a strange reaction as it started to cut out, but only in the Porsche Curves. In fact, I pulled onto the grass at one point, but then it picked up and took off, and did the same thing the next lap in the same place.

“Mags” then took over for the finish, and was very late in coming round on the last lap, having waved frantically on the previous trip past. The checkered flag came out and eventually the little Riley stuttered in on very few cylinders, but nevertheless still holding 40th place after the first few quick laps. We were still quite pleased to have 23 runners behind us after that bit of drama. It wasn’t 2nd overall as the car had done in period, but of course the car was new then, not 74 years old!

Owning a Riley

Such is the popularity of Rileys that many of them have been either preserved or rebuilt, especially in Britain and Europe. They are amazingly practical and durable, and even six SU carbs is not beyond the capability of a good mechanic. There are endless races for pre-war cars worldwide now, and parts are abundant, with many Riley specialists capable of finding components or making them to original specs. The flexibility of Riley cars is that essentially road-going machines could turn their hand to record breaking, sprints, hillclimbs, rallies, and endurance races.

You will never need a simulator again once you’ve had anything like the pre-war Riley experience at Le Mans—or even on that road from your house out into the beckoning countryside.

SPECIFICATIONS

Engine: 6 cylinder

Capacity: 1458-cc

Bore and stroke: 57 x 95.2 mm

Cooling: Water cooled

Carburetion: Twin triple SUs

Chassis: Deep channel steel frame with tubular steel cross-members

Steering: Riley worm and wheel pattern

Brakes: Heavy duty drum brakes

Transmission: Pre-selector or Riley standard 4-speed gearbox

Tires: Dunlop Racing 5.00 x 19

Weight: 914 Kg.

Wheelbase: 2477 mm (97.5”)

Resources

Many thanks to John Ruston, Ian and John Poulson, and Lee Maxted-Page for their generous help throughout.

Birmingham, A.T. Riley – The Production and Competition History of the Pre-1939 Riley Motor Cars G.T. Foulis & Co. London 1967

Riley, R. Race To The Top Mercian Manuals Balsall Common, UK 2003