1957 Kurtis Kraft 500G2

When Champ Cars made a very rare appearance in Europe a couple of years ago, many of us thought this would be a dream come true for those people who had never been to Indy or to any important oval race. I dragged as many friends as I could to the first race at Rockingham, mainly because I hadn’t had the experience myself and I thought it was something that couldn’t and shouldn’t be missed.

I think I was right. The cars flying out of Turn Four at the new Rockingham Speedway at full tilt came at you so fast you couldn’t catch your breath and you twisted your neck as you tried to follow them down the straight. But it was a commercial and “racing” failure. Not enough people turned up, with a circuit that wouldn’t dry out, Zanardi’s horrendous crash at the Lausitzring…and 9/11…cast a pall over the spectacle, and the foreign venture didn’t work. Not many Europeans got to see Indy cars on an oval, and probably never would. As an American who had turned rapidly into a road racing enthusiast in his early teenage years, midgets, sprint cars and Indy Roadsters had been left behind, and I’d have to admit that I saw them as rather “second class” racing at the time, so I was looking for a second chance to capture what I had missed.

Indy cars had made one or two previous attempts to break into Europe, once in the ’50s when they challenged the Europeans to a straight fight at Monza, and then in 1976 when USAC made a short foray to Brands Hatch and Silverstone. I did get to the Silverstone race and there was the amazing sight of A. J. Foyt and Danny Ongais wrestling with turbo power on a damp road circuit…but the weather took the excitement out of it, and it didn’t capture anyone’s imagination then or nearly 30 years later. The potential seemed obvious, yet it just didn’t work.

So when British historic racer Stuart Harper, rather more renowned for his exploits in VSCC racing with a three-wheeler Morgan, started doing well with an unlikely looking front-engine Indy Roadster both in the UK and on a trip to Phillip Island in Australia, that old surge of nostalgia came back. Stuart doesn’t live far from me and has his workshop in Northampton, so when a track-day at the little-used Rockingham oval came onto the schedule, it seemed a perfect opportunity to finally delve into the Indy car phenomenon.

Kurtis Kraft

Frank Kurtis shares a similar background to that of the other Indy greats, Harry A. Miller and Fred Offenhauser, both of whose parents had emigrated to the United States, which meant that all three men had inherited the “old world” work ethic and dedication to craftsmanship. At the age of 12, living in Utah, Frank helped his father in the family garage, learning to fabricate his own projects and modifying a Model T Ford at age 13. When the family moved to California, Frank began an apprenticeship at Don Lee’s Cadillac business in Los Angeles, which provided the opportunity to work on custom and exotic cars for a 14-year spell including an introduction to racing car construction. Lee’s son Tommy became an avid midget racer and entrant, helping to keep Offenhauser’s engine company in business during the Depression. Lee commissioned Kurtis to build an Offenhauser-powered racecar in 1936 and the combination of Lee’s money and the artistry of Kurtis and Offenhauser was the start of an enduring racing legend. Kurtis’s car was the Atlas Chrome Special, which made its debut at Ascot Stadium and was considered one of the most beautiful cars ever to appear on that deadly, 5/8-mile, oiled dirt bowl.

After the war ended in 1945, fans were anxious to get back to what had been the rapidly growing sport of midget car racing. There were few constructors left after the war, as most of the prewar midgets had been built by the individual owner-drivers. Kurtis designed a new tube-frame midget for either the 110-cu.in. Offy motor or less costly 136-cu.in. Ford V-8 Flathead. Five years later, virtually every midget race across the United States was being won by a Kurtis-Offy, or Kurtis-Kraft Offy, as the Kurtis car building business had become known. Though Kurtis’s design thinking and advanced metal work techniques would take him into sprint cars, midgets, sports cars, dragsters, Bonneville record cars and even road cars, it was at the Indy 500 where Frank Kurtis became famous and influential.

From shocking the racing world by starting a racecar production line in the 1940s, Kurtis went on to build hundreds of midget cars, 110 Indy cars, some 150 sports cars, 1,500 karts, quarter, three quarter and micro-midgets, and several sprint cars among other things. According to Gordon Elliot White: “Between 1941 and 1965, more than a third of the cars that ran at Indianapolis were Kurtis-built. In each of the six years, 1952–1957, more than 20 of the 33 starters came from Kurtis shops in Los Angeles and Glendale, California.” This was also the great period of Offenhauser engine success, so the combination was formidable.

The first Kurtis Indy appearance was in the hands of Sam Hanks in 1941. It was not an auspicious beginning as the car was wrecked in postqualifying practice. The numbers increased through the late ’40s, and there were 28 Kurtis chassis entered in 1950, most with Offy engines, though the occasional Novi, Dury, Cummins Diesel and Winfield had also been found in the Kurtis. Johnnie Parsons finished 2nd in a Kurtis-Offy in 1949, and then brought Frank Kurtis his first Indy win in 1950 in the Wynn’s Friction Proofing Special. Many victories at other championship races that season followed. In the next seven years, Kurtis won four times, was 2nd twice and 3rd once.

Kurtis 500G

The early Indy cars were mainly referred to plainly as Kurtis-Offy or whatever other engine might be in the car. However, at Indy, cars were almost always known more widely by their individual names…the Bowes Seal Fast Special for example. Americans were very quick to exploit commercial opportunities with colorful cars carrying the names and logos of either the owner/driver’s own business or his sponsor. There were few references to a Kurtis model designation in the early days, but the Kurtis-Kraft 2000, or Kurtis 2000, first appeared in 1947. Kurtis’s first tube-frame chassis had been built in 1946, a switch from the traditional rail-frame approach which used channel-section steel as per period passenger cars. Kurtis developed a much stiffer frame from aircraft-quality tubing, and he offset the engine two inches to the left, which allowed the driver to be positioned next to the driveshaft, and also lowered the center of gravity and the profile. He wasn’t the first to do this, but he developed and succeeded with the concept. The 1946 car was 11th at the Indy 500 and set the trend for the future. The KK2000 was little more than a scaled-up version of the midget car, two feet longer and widened to suit the 270-ci. Offy, which was 1-1/4-inch wider than the midget Offy motor. The KK2000 had distinctive hairpin radius rods and semicircular radius rod mounts. The new car used parallel 1-1/2-inch tubes with a flat steel section between them, which added stiffening.

The 1950 KK3000 had independent front suspension, a solid, open-tube Halibrand rear axle and parallel torsion-bar springs with the hairpin-shaped radius rods. The 1951 KK4000 was the last Kurtis for both Indy and dirt tracks. It had conventional solid axles suspended with parallel torsion bars inside the tubes, and it was really a bit of a throwback to the KK2000 and was much better on dirt tracks. The KK500 of late 1951 was a wider and lower version of the earlier cars. The handling with this improved offset car was much better. It had the usual solid axles and torsion bars. Only one of these cars, the Keck Special, was a true offset roadster, since the three KK500As had stock block engines, which were more difficult to offset. Eight KK500Bs were built in 1953 with suspension changes. The C, D, E and F models, built until 1956, were largely refinements of the earlier cars.

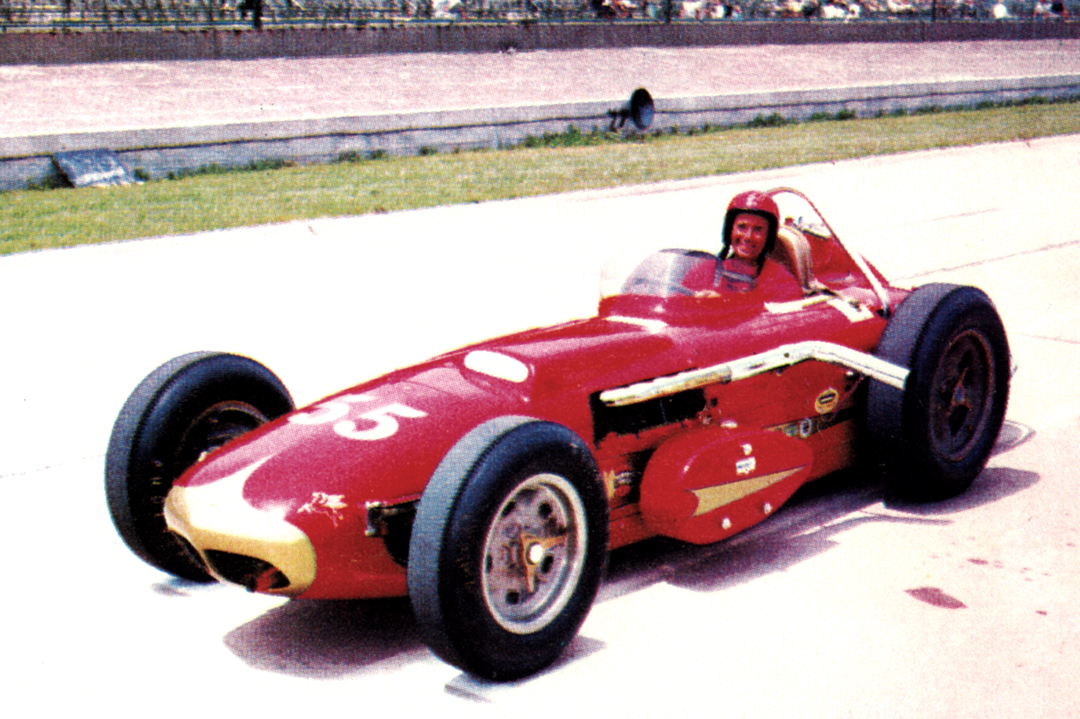

Only two KK500G chassis were constructed in 1956, one for George Bignotti and one for George Walther, Jr., and these had drag link steering on the right and rather large scoops on the hood. These cars were lower than all the previous KK500 models. Front torsion bars were located below the axle, and the two cars had oval grille openings with a surrounding chrome bumper. Internal business problems plagued Kurtis in 1957, resulting in his having a hard time concentrating on design. The KK500G2 was essentially a 500G with “slight refinements.” The engines were offset to the left but the degree of tilt varied with different customers, with differing degree exhaust and intake arrangements. Most KK500G2s had drag link steering with the distinctive chrome-surround grille. There were 14 G2s built.

Chassis G2-14

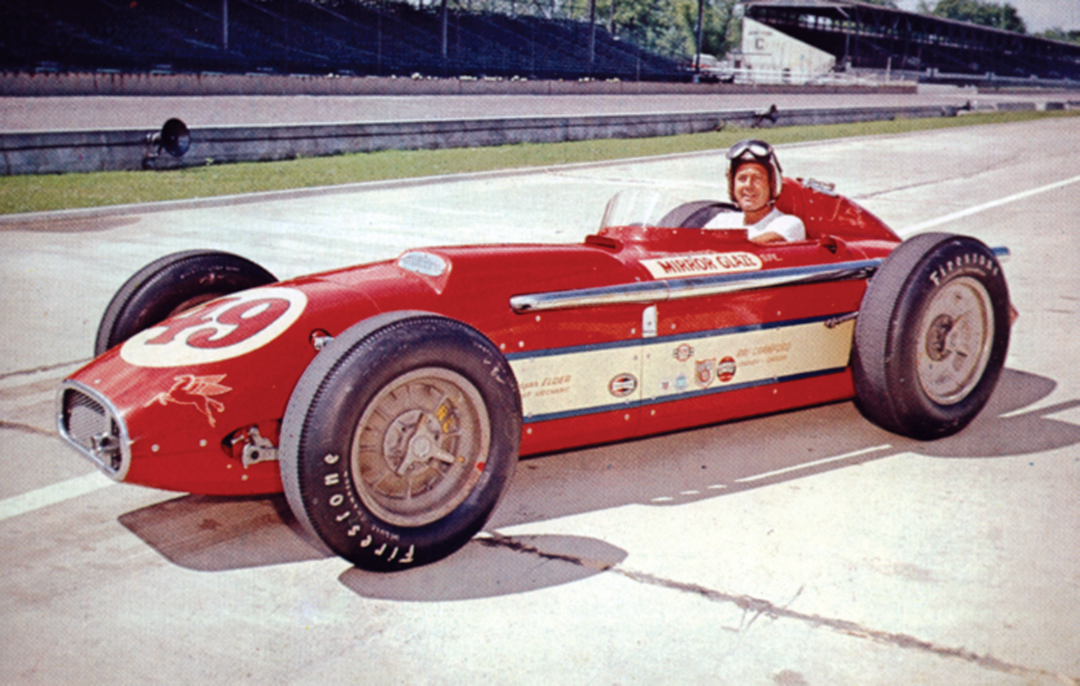

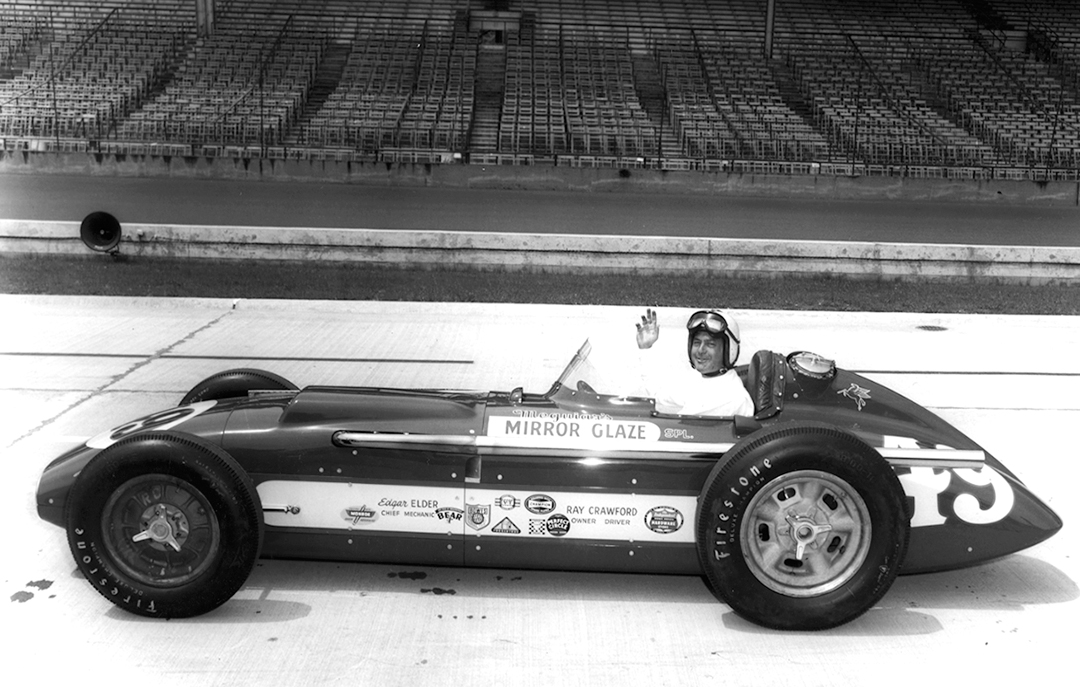

Ray Crawford was a veteran Kurtis customer, his first appearance in one of Frank’s Indy cars having been at the Milwaukee 100 Mile in June 1954, with his “paved track” 500, the Crawford No. 32 Special which was too slow to start. He didn’t qualify at Darlington and was 18th in a KK4000 at Springfield. He had further midfield placings that year, and was at Indy in 1955 in a 500B, finishing 23rd when the engine wouldn’t restart at 111 laps. His 4000 and 4000D weren’t very quick that year. He started his 500B 17th at the ’56 Indy 500 but crashed, and did a few dirt races in the 4000 as well.

Crawford bought the car you see here in 1957, and as the Meguiar Mirror Glaze Special, attempted the big race at Indianapolis, but failed to qualify at 139.099 mph. As it happened, there were at least two other drivers in that race who would later race this car. Then life for G2-14 took a very interesting turn. A spectacular-sounding challenge was thrown down at the end of 1956 to a range of cars conforming to various international formulae. This was the Monza 500 Mile Race, or as it became known, the “Race of the Two Worlds” or Monzanapolis. The idea was greeted with much excitement in some quarters. It was open to Indianapolis, Grand Prix and sports cars. The race was to use the fast, banked portion of the Monza circuit, a track that had caused many difficulties for F1 cars. The Europeans, while arguing that the Grand Prix cars would out-handle and out-accelerate the Indy cars, had all decided, on the grounds of safety, to abstain, claiming that the Americans had a great horsepower and set-up advantage. Only David Murray and the Ecurie Ecosse took up the challenge and sent three D-Type Jaguars to represent Europe…or Britain…or Scotland! It turned out that two of these would be the cars that finished 1st and 2nd at Le Mans only the week before. Two Maseratis were sent at the last moment, one failing to manage a qualifying time, and the Jean Behra car being withdrawn after practice.

Six of the ten American cars were Kurtis chassis, though two of them would suffer fuel leakage problems after the pounding on the banking, the same thing that affected cars at Indy, and harmed Kurtis’s reputation. Cigar-chomping Jimmy Bryan won the first heat from Pat O’Connor, Andy Linden and Eddie Sachs. Ray Crawford in G2-14 was 7th, and the three Jaguars were 8th, 9th and 10th. Bryan was the winner again in the next heat, while Crawford had moved up to 4th, and the Jags were 5th, 6th and 7th. Ruttman won the third heat from Bryan with Crawford classified 8th. This meant Bryan won overall from Ruttman and Parsons and the three Jaguars with Crawford 7th. The general feeling was that, if the race had been run as one 500-mile race, the Jaguars would have won and none of the Indy cars would have finished. So perhaps the Grand Prix teams got it wrong. The press said the race would never happen again.

After his good showing at Monza, Crawford showed up at Milwaukee in August, but again could not qualify. The determined driver was back at Indy in ’58, but again could not get into the field, but then neither did Juan Manuel Fangio in George Walther, Jr.’s car.

Much to everybody’s surprise, the Automobile Club of Milan returned to Monza for a second attempt at the Race of the Two Worlds. In addition to 12 Indy cars, there were Ferraris for Hawthorn, Musso and Schell, a special Maserati for Stirling Moss, D-Type Jaguars for Masten Gregory and Ivor Bueb, and a single-seater Lister-Jag for Jack Fairman. The Dean Van Lines car was driven by Juan Manuel Fangio.

Luigi Musso delighted the many Italians present, driving a Ferrari like a man possessed, on opposite lock on the banking, taking pole position at 281 kilometers per hour, much faster than the speeds at Indy. Fangio was 3rd quickest and Ray Crawford had G2-14 in 12th also faster than it would go at Indy. Musso and Eddie Sachs had a good battle at the start of the first heat, but Jim Rathmann took over and won, with Moss 4th. Fangio didn’t start as he had a cracked piston, which wasn’t repaired until the third heat, and then only lasted a lap. Crawford was 10th.

Rathmann also won the second heat, with Crawford 8th. Rathmann won again in the last heat, which meant overall victory as well. Stirling Moss had a huge crash on the banking and retired. Jimmy Bryan was 2nd in the heat and overall, with Hawthorn and Phil Hill sharing 3rd place. Ray Crawford’s 4th in the heat meant he was 4th overall—the car’s best and perhaps most unusual result in its long career.

Crawford finally sold the car to Ollie Prather who also engineered it at the 1959 Indy 500 for Bill Homeier. Running as the Go Kart Special, it threw a rod and failed to qualify after its valiant drive at Monza. In 1960, it was again entered at Indy by Ollie Prather as the Go Kart Special for Eddie Russo. Russo was classified 26th after crashing on lap 84 after running on worn tires. He was injured but recovered. Prather was back again in 1961, this time with the car as the Schulz Fueling Equipment Special, with Jimmy Daywalt driving. The car retired on lap 27 with a broken brake line. In 1962, Prather put the great Jim McElreath in the car and he rewarded Prather by starting 7th, finishing 6th, getting Rookie of the Year and over $10,000. This was by far the car’s best performance at Indianapolis. McElreath ran the car at the Milwaukee 100 (14th) but, still in Schulz colors, Leroy Neumayer couldn’t qualify for the Milwaukee 200. Prather had Ralph Liguori in the car at Indy in 1963, but it didn’t make the start. Liguori was 16th at the Milwaukee 100 that year, and in early 1964 Johnny Boyd was 14th at the Phoenix 100 for Prather. Liguori tried unsuccessfully to qualify what was now known as the Ollie Prather Special at Indy in ’64, but that was the last attempt at the Brickyard. Jimmy Daywalt did some tire testing for Firestone with the car in ’64, turning laps at over 180 mph.

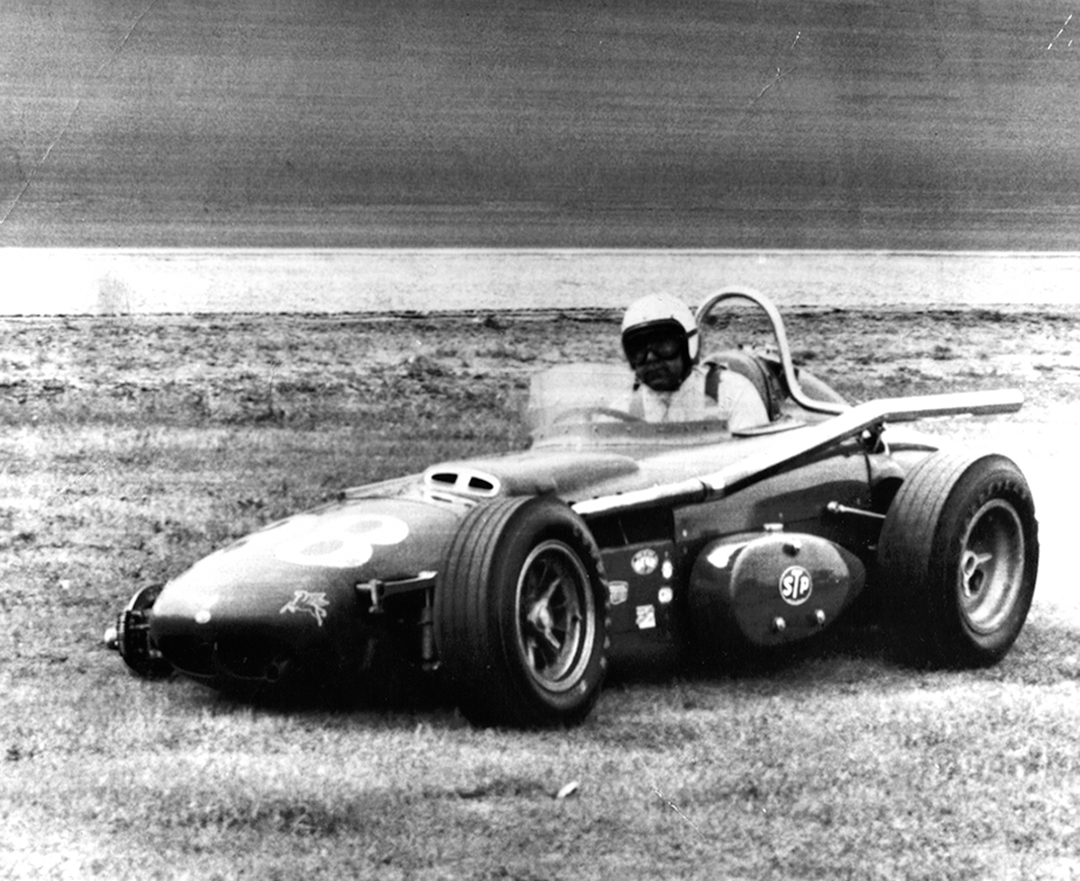

Prather finally sold the car to Canadian Bill Chapin, who then sold it some years ago to Brian Classick in the UK. It then went to a few other owners including Ed Hubbard. British historic enthusiast John Guyott then had it in 1992 and did a lot of work to make it “less lethal” to drive. Four years ago it was purchased by Stuart Harper who has really made the car driveable again. Chapin contacted the author to say he wished he still had the car! I am not surprised! Stuart Harper has been “campaigning” the car in historic events, and has managed to give the car its very first wins, with superb performances at Silverstone, Oulton Park and Phillip Island not the places you would expect this car to be winning.

Driving the Veteran Kurtis 500G2

There was another front-engine Indy Roadster active in British historic racing for a number of years, and I often found myself gazing into the spacious and very “un-European” cockpit of the wonderfully named Turtle Drilling Special. When Ian Raybould and Iain Macauley of Trackdays.com said they thought it would be nice to have a genuine oval racer at one of their Rockingham track days, the affable Stuart Harper and wife Penny were happy to trailer their prize possession the few miles to the impressive racing complex.

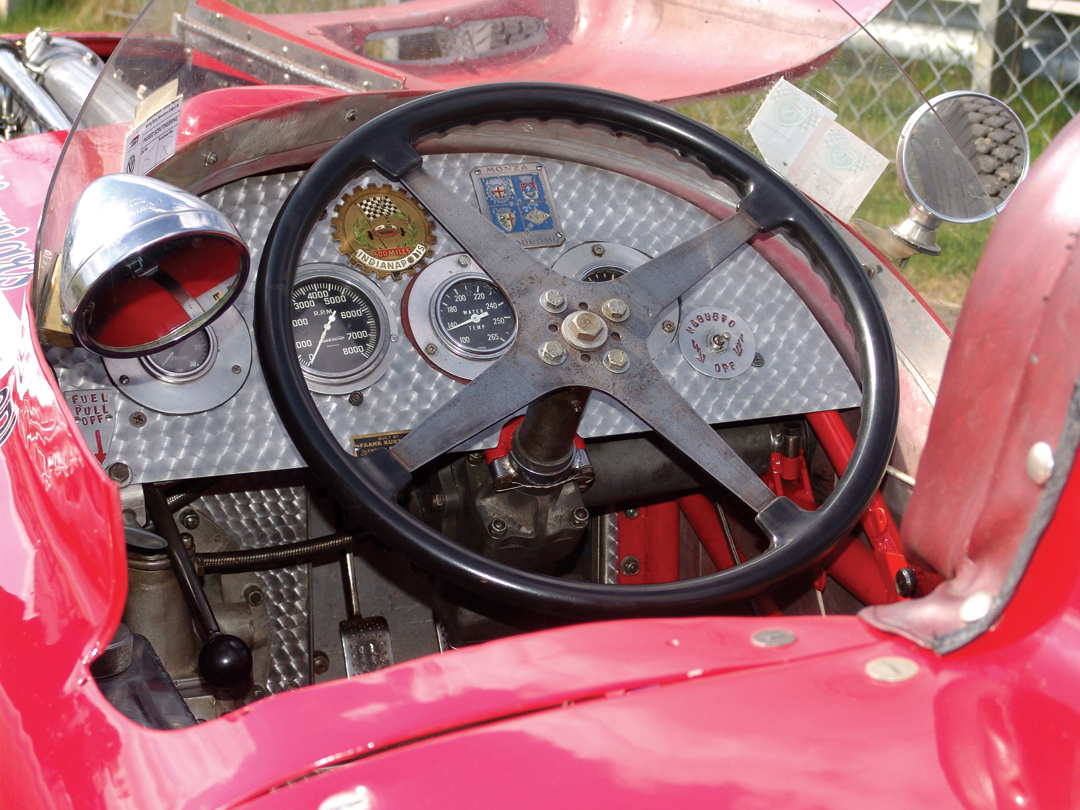

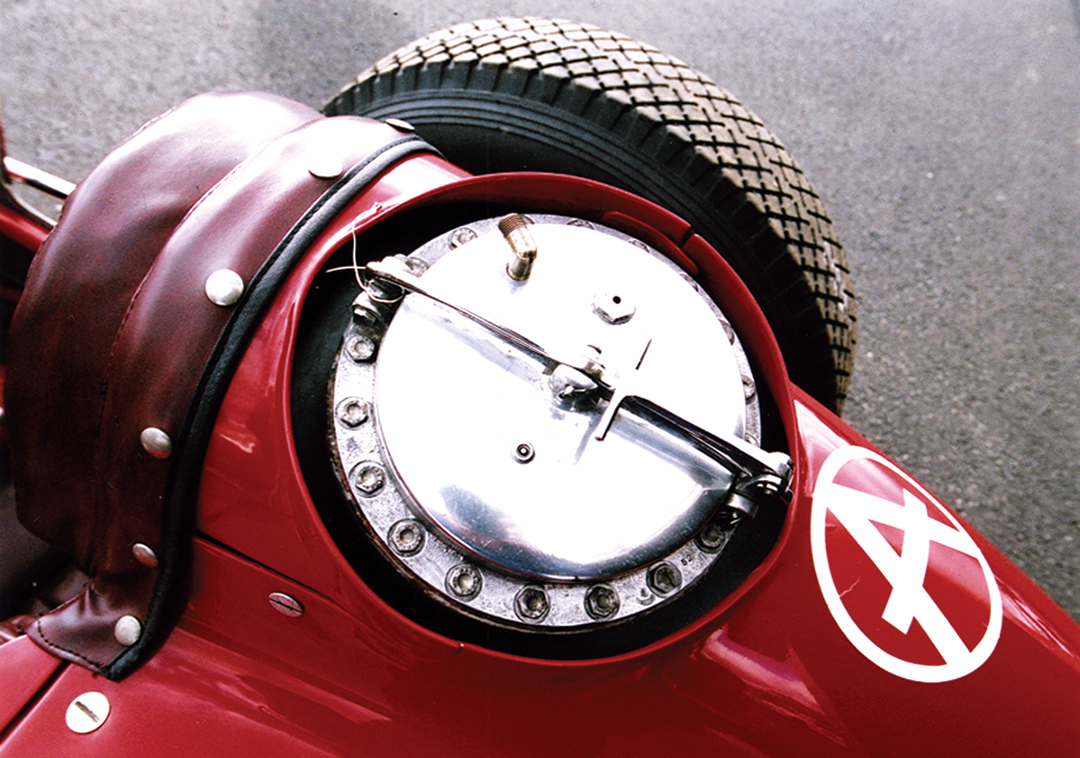

There I was again gazing into the past. Stuart’s Kurtis still has its Monza and Indy badges as well as the chassis plate with KK500 G2-14 on the original, untouched alloy dash. A huge four-spoke steering wheel dominates the cockpit, with a rather plush and comfortable leather seat. The driver’s compartment is spacious indeed, allowing the ominous-looking driveshaft to sit alongside your left leg, with room remaining for an oil tank between the shaft and the chassis tubing. There are temperature gauges and a rev counter reading to 8,000 rpm, the magneto on-off switch on the right, and the gear-lever for the three-speed gearbox over on the left. There’s also a fuel mixture regulator. There is plenty of room to work in here, only a lap belt to hold you in, and masses of period atmosphere. There is an inside and an outside mirror and they provide good rearward vision. The leather-covered headrest contains a large fuel filler—this car runs on alcohol as true Indy cars do. The windscreen, semi-wraparound, provides suitable protection. The bodywork on the left side is higher than on the right, so there is metal between the high exhaust and the driver. This means you have a really good view of the right side suspension, but your elbow is awfully close to the rear wheel!

After my “briefing” which was mainly about enjoying the experience, Stuart grabbed the big starter and we spun the great Offy engine into life. There was a short warning about hunting around for the gears, apt as it turned out, as I accelerated out of the pit-lane in third gear, rather than first, which said something about the torque in this 450 bhp engine, as well as my “hunting” ability, or lack of it. Stuart describes the gear ratios as “terrible,” with first being a super low gear, second being low and more than adequate for starting, and third for everything else. This probably helps Stuart put all his effort into hanging onto this great machine on tricky road courses, rather than searching for gears.

The four-cylinder Offy spit and banged on the over-run at low speeds as I found my way around the straight-forward controls and checked the gauges. With a few laps out of the way getting some good photos, it was time to tick another box on my “great events” list. I had worked out that this was probably the first time a front-engine Indy Roadster had run on a British racing oval. I know we may get letters on this, but I think that this is accurate. Simultaneously, I got another jolt when I realized just how close your head comes to the wall in a car like this, as it uses that torque and flings itself out of each high-speed corner. The solid rear axle setup, naturally, means you have to work the car into the corner. If you lift, it understeers, and that means wall, though it is not too difficult to get used to this on the oval. A road circuit is something else again!

In fact, you seem to have the quintessential “Indy experience” in a car like this as soon as you go anywhere near the limits in any given corner. When the car is up to speed, the novice like me reaches the corner faster than he ever has before and it becomes a matter of balancing the thrust and torque as you see just how the chassis is going to handle it. The torque is terrific, you can accelerate from 1,000 rpm to 6,000 rpm quite smoothly and without drama. Even at modest speeds, there’s a fine line between coming out of the corner on the right line, and not! Go in a bit fast and finding yourself heading for the wall is not nice, but that is how you do it. Oval racing is all about running as close to the wall as possible. This is not the moment you want to listen to Smokey Yunick’s CD on Indy drivers in tee-shirts, crappy helmets, fuel tanks all over the place and no protection. I respect today’s Champ Car drivers, but you can hit a wall at 200 mph and walk away. In the ’50s, if you had a sudden meeting with the wall at anything over 100 mph you were in serious, life-threatening trouble.

Yet, with all the threat, the throb of the Offy out the back and that immense surge down the straight is incredibly exhilarating. You have a few seconds to get your speed right and aim into the next bend on the right line, sailing closer and closer to the wall. Rockingham is a D-shape, and the corners are very quick. I had a micro-second to glimpse a lot of people in the pit-lane having the whipped neck experience as the howling Kurtis-Offy went by. There was no such thing as trying the brakes. It was all about speed and a line—as simple as that. With a bit of warmth into the Dunlop Racing tires (7.00-16 front, 7.00-18 rear) on beautiful Halibrand wheels, there is a bit more feel, but that is something for Lesson 2. For now, I can sit here and watch that lovely front torsion bar suspension working away, like it did at Indy and Monza.

Specifications

Chassis: Multi-tubular frame chassis to aircraft specs; offset to left

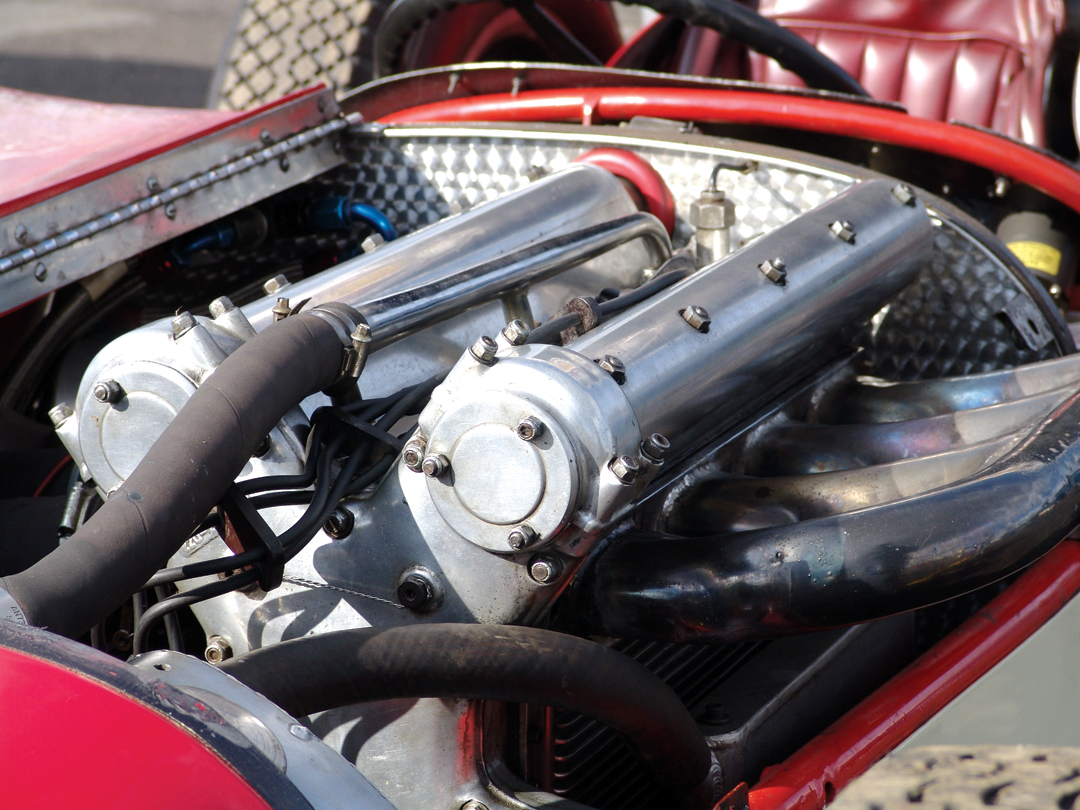

Engine: Offenhauser

Cylinders: Four, in-line

Capacity: 4.2 liters, 255 cubic inches

Camshaft: Twin overhead cams

Power: 450 bhp

Compression ratio: 14:1

Fuel delivery: Hilborn fuel injection

Ignition: Magneto

Gearbox: Halibrand 3-speed, based on Ford truck

Drive: Locked spool 3-inch solid drive

Rear axle: Halibrand quick change

Brakes: 4 wheel discs

Fuel: Methanol

Tires and wheels: Dunlop 7.00-16 front, 7.00-18 rear; Halibrand wheels

Resources

Many thanks to Stuart Harper for his help and generosity, to Trackday.com and Rockingham Motor Speedway.

White, G. E. Kurtis-Kraft—Masterworks of Speed and Style. MBI Publishing, Minn., USA, 1991.

White, G. E. Offenhauser—The Legendary Racing Engine and the Men Who Built It. MBI Publishing, Minn., USA 1996.