You could be forgiven for thinking that this geography lesson has nothing at all to do with Grand Prix competition, but you would be wrong, as the Parque Montjuich provided us with one of the greatest circuits of all time. Unlike many of its contemporaries that were built on disused airfields, Montjuich Park clings to the side of the hill from which it takes its name. More a mini-Nürburgring or tree-lined Monaco, Montjuich twists and falls, swoops and climbs throughout its 2.35-mile lap. Starting close to the summit, the track heads uphill and left before suddenly plunging down toward the left-hand hairpin, El Angulo de Miramar. On the approach to El Angulo, travelling at over 150 mph, the cars were invariably airborne as they came over the crest at Rasente. Having landed on the downhill gradient it was then the driver’s job to slow the car enough to make it around the 180-degree corner, a test of man, machine and, particularly, brakes.

After El Angulo, continuing downward, the track curves right onto a short straight ending at the next 180-degree, first-gear, right-hander, Rosaleda. Tumbling on downward through the left turns of Font del Gat and Teato Griego, then snaking right and left along the Passeig de Santa Madrona, the road bears right at Vias onto the first of only two decent straights in the whole lap, this one ending with a 90-degree right at Guardia Urbana.

Now at its lowest point, the circuit runs along its second straight toward La Pergola from where it turns left and starts to climb back up the hill. Sweeping right shortly afterward at Pueblo Espanol and, still climbing, there is short semi-straight before embarking on an almost everlasting left-hand sweep that climbs all the way back to Sant Jordi and onto the start straight.

An affordable taxi ride from Barcelona’s city center, Montjuich seemed to have everything, each lap presenting the challenge of corners ranging from hairpins to fast sweeping bends, flat-out crests and difficult downhill runs with equally taxing uphill sections. Finding the ultimate setup was a tricky business, and great skill was required on the driver’s part to put that to good use on the track. Montjuich was voted by the British magazine Autosport as one of its top 10 circuits of all time, and racing there was indeed spectacular, but also fraught with danger.

As with most temporary street circuits, particularly those of 40 years ago, there was little room for error and precious little in the way of escape roads or runoff areas. The whole circuit was lined with ARMCO barrier only inches from the tarmac and, in many places, only a few feet behind that were trees or a stone wall. I well remember standing at one point photographing the cars travelling only inches away and feeling the ARMCO shudder at each passing, even the bravado of youth couldn’t stop me moving quickly on. Perhaps it would only be a matter of time before the confines of this testing track took their toll.

The Penya Rhin Grand Prix moved to the new Montjuich circuit in 1933, with Jean Zanelli taking victory in his Alfa 8C Monza. The new circuit immediately showed its strength with the great Tazio Nuvolari only managing 5th place, two laps behind Zanelli and nursing an overheating Alfa to the finish. During the three following years, Montjuich hosted the Penya Rhin and provided three separate winners. The 1934 race became a fight between Nuvolari, racing for Maserati, and Achille Varzi in the P3 Alfa, but yet again Montjuich foiled Nuvolari.

Photo: Roger Dixon

Having led from the start, he retired with engine problems, leaving a trio of Ferrari-entered Alfa P3s to take a one-two-three victory. The following year Mercedes-Benz was present with two W25Bs for Rudolf Caracciola and Luigi Fagioli, who took the flag 47secondss ahead of his teammate with Nuvolari the only other driver on the same lap. Nineteen-thirty-six was at last to be Nuvolari’s year. Both Mercedes and Auto Union entered teams, each including a short-wheelbase “special” for the Montjuich course. Neither of these cars performed well, however, leaving the door open for Tazio’s 12-cylinder Alfa to take the flag. Despite still recovering from broken ribs suffered in the Tripoli Grand Prix a few weeks earlier, and despite an additional pit stop for fresh tires Nuvolari finished 3.4 seconds in front of Caracciola’s Mercedes W25K.

While the Penya Rhin races were non-championship events, it’s obvious that all the teams treated them very seriously and some 75 years on we can only imagine the spectacle of these 1930s monster Grand Prix machines as they and their drivers did battle around this circuit. A civil war immediately followed by a world war stopped any further Grand Prix action at Montjuich for the next 33 years.

Only in 1968 did Grand Prix racing return to Spain at the newly constructed Jarama circuit just outside Madrid, but due to the fierce inter-regional rivalry that exists in Spain the Catalan area around Barcelona pushed for a revival of Montjuich and managed to persuade the Spanish federation that they should alternate yearly with Madrid. Consequently, in early May 1969, the Grand Prix circus set up camp at Montjuich using the old Olympic stadium as their paddock.

As Jackie Stewart says it was the era of “those stupid aerofoils” and all the teams arrived with a tall-winged variation on the F1 theme. With the benefit of hindsight the cars were obviously unsafe with giant wings mounted high up into the airflow supported by flimsy uprights that in turn mounted directly onto the suspension castings. As the cars raced around the circuit these great wings twitched and wobbled with every bump and undulation. Nonetheless, despite resembling 1920s biplanes, the cars were regarded as cutting edge.

Photo: Roger Dixon

Only 14 cars were entered, with two works cars from Brabham (BT26s for Brabham and Ickx), Matra (MS80s for Stewart and Beltoise), Lotus (49Bs for Hill and Rindt), McLaren (M7s for McLaren and Hulme) and BRM (one P133 for Oliver and one P138 for Surtees). Single entries came from Reg Parnell (a BRM P126 for Rodriguez), Rob Walker (a Lotus 49B for Siffert), Frank Williams (a Brabham BT26 for Courage) and finally Ferrari (a 312 for Amon).

Practice got underway the Thursday before the race and within a few minutes Rindt pitted with damage to his front suspension, not as a result of pressure from an aerofoil but from a collision with a dog. Chris Amon topped the charts at the end of the session, his Ferrari was almost a full second quicker than the next man, Graham Hill. Amon could not improve during the second session and his time was equalled by Hill, with Stewart just 0.02s behind.

Overnight on Friday the Lotus mechanics toiled and both 49Bs arrived for Saturday’s final qualifying session sporting enlarged front fins and wider rear wings. Rindt quickly demonstrated that the modifications were for the better by posting a 1:26.8, beating Amon’s previous best by 0.08s, but shortly after the Ferrari driver replied with a 1:26.2. Colin Chapman and senior Lotus mechanic Bob Sparshot then appeared in the pit lane and taped a four-inch-deep aluminium lip along the rear centre section of Rindt’s wing. Jochen went out again, improved his time, and snatched pole by half a second.

By the end of the first lap of Sunday’s race Rindt had a clear lead over Amon, followed by Siffert who had made a blinding start from 6th on the grid. On lap six the positions remained the same but with Hill now hot on Siffert’s gearbox, and on lap seven Lotus passed Lotus with Hill demoting Siffert to 4th place. On lap nine Hill crashed when his rear wing collapsed, pitching the 49B into the guardrail just past the pits. Fortunately, Graham was unhurt but the car was wrecked. Ten laps later Rindt’s Lotus suffered the same failure at exactly the same spot and his 49B crashed into its sister car and ricocheted back into the middle of the track with its driver trapped underneath. Graham rushed to help his teammate, who was eventually extricated from the wreck bleeding heavily from a broken nose.

Photo: Roger Dixon

This left Amon with a 24-second lead over Siffert who in turn was 6 seconds up on Stewart. At the end of lap 31 Jo coasted in with a blown engine in the 49B, giving Amon a huge lead on Stewart until lap 57 when the Ferrari’s engine, which had been giving Amon some concern for many laps, finally called it a day. This gifted the lead to Stewart, who then led Ickx’s Brabham by nearly a minute. Seven laps later Ickx survived a heart-stopping moment when his Brabham’s rear wing crumpled, forcing him to limp back to the pits with something resembling a giant chicken wishbone perched above his rear wheels.

JYS had already eased off and was able to nurse the Matra to a comfortable victory en route to his first World Championship, “The MS80 was the best Grand Prix car I ever drove,” he said some years later, but we can be fairly sure he wasn’t referring to it in its “big wing” configuration.

There is no doubt that during this first post-war return to Montjuich the circuit had tested the new wing culture to its limit and in many cases beyond. Interestingly, Amon’s Ferrari 312/69, which was the class of the field for most of the weekend, was the only car to have its aerofoil mounted to the chassis as opposed to its suspension. Two weeks later at the Monaco Grand Prix the big wings were banned and only much smaller versions fixed to the chassis were permitted.

For Montjuich’s 1971 Grand Prix the entry list was considerably larger than before, as this time 22 contenders arrived in the Spanish capital to do battle. Heading the list were two Gold Leaf Lotus 72s for Fittipaldi and Wisell, two Brabhams, a BT33 and a BT34 for Schenken and Hill, respectively, two McLarens, an M14 and M19 with Gethin and Hulme at their wheel, one each Tyrrells 002 and 003 for Cervert and Stewart, two Matra MS120Bs for Amon and Beltoise and two Surtees TS9s for Stommelen and Surtees. Both Ferrari and BRM fielded three cars each, the Italian team providing 312Bs for Ickx, Regazzoni and Andretti, and the boys from Lincolnshire running two P160s for Rodriguez and Siffert plus a P153 for Ganley. March had no less than four 711 models running, one entered by Frank Williams for Pescarolo and three by STP, two Ford-powered chassis for Peterson and Soler-Roig, plus an Alfa-propelled tub for De Adamich.

Photo: Roger Dixon

Each of the three practice sessions were scheduled to be run in the cool of the evening. For the first session, on Thursday, however, the pits did not prove to be cool for Pedro Rodriguez when a fuel fire erupted around his BRM. Fortunately, quick-acting mechanics pushed the car, with the driver still in it, out of the inferno and into safety. Stewart topped the times for the day with Ickx 0.3s behind.

On Friday evening the 12-cylinder runners headed the field, as they had done for most of the season thus far. Ickx-Ferrari, Regazzoni-Ferrari and Amon-Matra held the first three slots, with Stewart’s Tyrrell-Ford V8 squeezing into fourth just 0.3s ahead of Rodriguez’s BRM. In the cool of Saturday evening it rained heavily, consequently Friday’s times prevailed and the front row of Sunday’s grid was a 12-cylinder lockout.

Jacky Ickx used the advantage of pole position to take an immediate lead at the start of Sunday’s race. Stewart, however, managed to rocket through from the second row and elbow his way into 2nd place by the end of lap one, albeit 1.5s adrift of Ickx, with Regazzoni a further 0.5s down the line. The thirsty 12s had to carry a greater fuel load, a weight disadvantage that had not been a problem in practice, enabling Stewart in the lighter-fuelled Tyrrell to reel Ickx in slowly and when the Ferrari ran wide on lap six, Jackie took the lead.

Photo: Roger Dixon

As the race progressed Ickx stemmed the deficit at 3.5s for many laps and then gradually Stewart eased it out to eight seconds. In the last quarter Ickx attacked again, but it was too late and the Tyrrell team took its maiden Grand Prix victory by 3.4 seconds, but not before Ickx had grabbed the lap record with a 1:25.1 in his efforts to catch up.

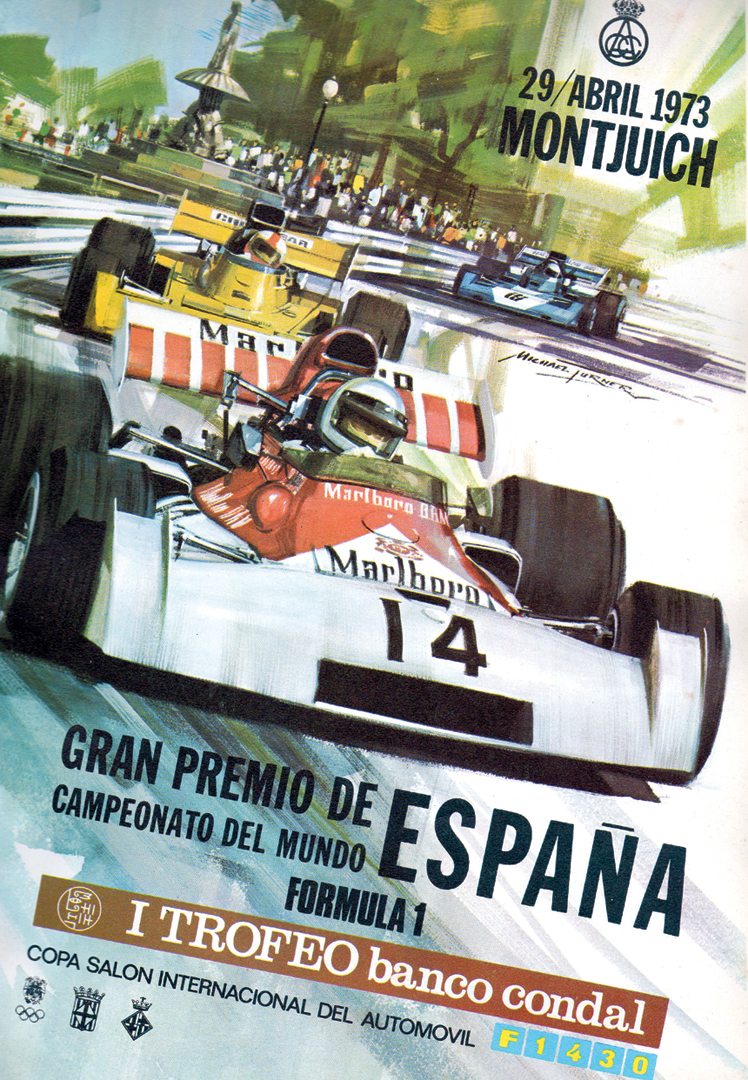

The 1973 event was to be my one and only visit to Montjuich, and the circuit impressed me immediately not only with its magnificent setting but also its driver’s challenge. As well as the first European Grand Prix of the season, this was also the first in which all cars had to conform to new F1 rules. Mainly aimed at safety, these new regulations required deformable (crushable) structures to be included into certain areas of the car, protecting the fuel tanks and particularly the driver from impact damage during an accident. To allow for this extra protection the overall minimum weight of the car was raised to 575 kg (1265 lbs).

Photo: Roger Dixon

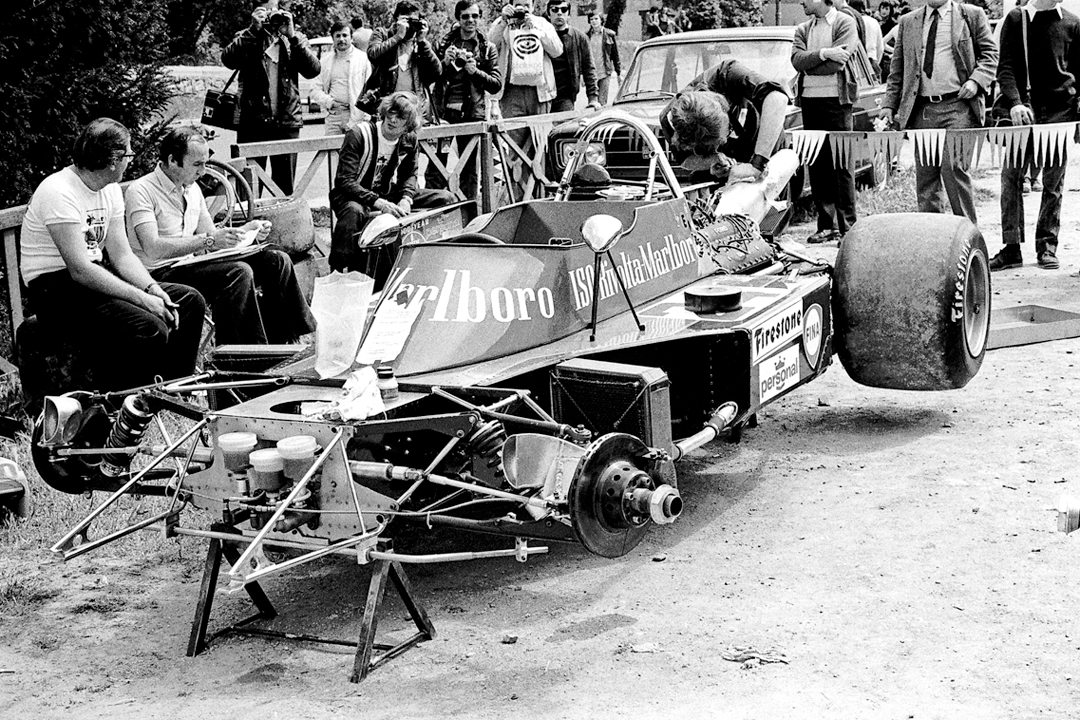

Brabham, McLaren, Shadow and Surtees had already built and used their new-spec 1973 cars previously, but Tyrrell, BRM, Lotus and March arrived with last year’s models extensively modified to comply with the latest regulations, while Ferrari and Iso-Marlboro arrived with completely new and untried machinery to hone into shape over the weekend.

Lotus JPS brought three 72s for Ronnie Peterson and Emerson Fittipaldi, Tyrrell had two 006s and a 005 for Stewart and François Cervert, Yardley McLaren unloaded three M23s for Denny Hulme and Peter Revson to share. Two wedge-shaped Ferrari B3s arrived from Modena for Ickx to choose from, and eventually he settled for the front-mounted-radiator model as the side-mounted version consistently overheated. Surtees-Fina rolled out two of its now familiar TS14As for Mike Hailwood and Carlos Pace, March had two 721s present for Henri Pescarolo and Mike Beuttler, Marlboro-BRM had four P160s for regulars Clay Regazzoni, Jean-Pierre Beltoise and Niki Lauda to play with, while Bernie Ecclestone’s MRD Brabham team produced two brand-new chassis of Gordon Murray’s very angular BT42 design for Carlos Reutemann and Wilson Fittipaldi. Three Shadow DN1 chassis arrived, two works UOP cars for Jackie Oliver and George Follmer, and a third, straight-out-of-the-box, never-turned-a-wheel Embassy Racing model ready for Graham Hill to shake down during the pre-race practice sessions. Another completely brand-new chassis came from the fledgling Williams team in the shape of Howden Ganley’s ISO-Marlboro IR, but Nanni Galli’s IR had been run so the team was proposing to transfer those settings onto Howden’s car to start with.

Despite the new safety regulations increasing the minimum weight of the cars, no fewer than 16 of the 22 drivers broke Ickx’s two-year-old lap record during practice. Peterson proved unbeatable, heading the timing sheets after both the Friday and Saturday sessions with a 1:21.8 lap each day, while his teammate struggled a little and switched chassis overnight on Friday, leaving him only one session to post a time. Saturday proved the warmer of the two days, and consequently Emerson’s best for that day left him down in 7th on the grid, nearly two seconds adrift of Ronnie. Denny “this is not one of my favorite circuits” Hulme grabbed 2nd spot by 0.02s from Cevert, who in turn was 0.5s up on Stewart. Jackie had a big moment in his spare chassis down at the bottom of the hill when he spun at Urbana, breaking three corners of his Tyrrell. Apart from the usual brake dilemmas, always present at Montjuich, virtually all the teams were in trouble with tire wear, as the newly resurfaced circuit was destroying the rubber provided by both Goodyear and Firestone. Tires were coming in with blisters, chunks of tread missing and edge splitting, and tire engineers were recording some astronomical temperatures. Blame was laid on the new surface and the heavier cars, but this was during practice with light fuel loads. What would a 75-lap race result in? It was to be hoped the rubber boys had good stocks.

Photo: Roger Dixon

The start of Sunday’s race was delayed by 20 minutes, which gave the Surtees mechanics just enough time to change Hailwood’s engine after he had wrecked the previous one during the pre-race warmup. At 12:20 the field blasted off toward El Angulo with Peterson just holding his lead into the hairpin as Hailwood left the pits in hot pursuit. By the end of lap one Ronnie’s JPS Lotus had already established a useful lead over Denny’s M23. Today’s F1 rules require that a car must use two types of tire compound during the race, well back in 1973 Peterson started with no less than three different compounds fitted to his Lotus 72, all at the same time! In an effort to stem the considerable tire degradation that was expected for the race the Swede set off with a set of intermediates on the rear, a hard compound on the right front and a soft one on the left front, an eclectic mix even by 1973’s less technical standards. In order to give this set of “allsorts” longevity, Colin Chapman instructed Ronnie to build a reasonable lead and then ease off.

By tour four Peterson could see Stewart, who had passed Hulme at the end of lap two, a reasonable distance behind and just inched out a little on the Scot each lap, with Hulme, Cevert and Fittipaldi embroiled in their own battle for 3rd place some distance behind. On lap 19 three in a bed became two after Denny pitted to change an imbalanced front wheel, leaving Fittipaldi harrowing Cevert for 3rd place. This continued until lap 26 when Cevert locked his overheating brakes into the first hairpin, allowing Fittipaldi through. François then pitted to have two punctured tires replaced. Twenty-one laps later there was a repeat performance, but this time it was Stewart’s Tyrrell in trouble at El Angulo as a front brake shaft sheared, forcing JYS to take the escape road.

Photo: Roger Dixon

Ronnie’s speed, combined with Emerson’s good fortune, looked set to give JPS Lotus a one-two, but all was not well with either car. Toward the end of lap 57, Lotus team manager Peter Warr was anxiously looking at his stopwatch, then along the track and back to the watch again. Fittipaldi flashed by. “No Ronnie,” exclaimed Warr. What had not been evident was that over the last few laps Peterson had been slowly losing gears, one at a time, and by lap 57 all his cogs had disappeared. Now Fittipaldi just had to keep his nose clean to take the win. This was easier said than done, however, as the tire gremlin struck again. His left rear had a slow puncture. Down on pressure and degrading badly, it made the Lotus a real handful. Snaking along the straights and wallowing through the corners, Fittipaldi was easy meat. Carlos Reutemann (Brabham BT42) had benefited from the attrition rate, creeping up into 2nd place and looked set to give the car its début Grand Prix win. Carlos had ten laps left with only four seconds to make up when the BT42 broke a driveshaft, allowing “Fortunate Fitti” to take it easy from then on. Take it easy he did, even giving some of the “pit-stoppers” a chance to unlap themselves—including the now 2nd-placed Cevert. Virtually flat, the Goodyear hung on and Lotus took its 50th Grand Prix victory, beating Ferrari to the landmark by one race.

Driving up into Montjuich Park on April 25, 1975, visitors would have been greeted by fantastic vistas of the harbor, floral gardens, a fairground, even a cable car down to the city below, but most notably by silence. The first qualifying session should have been under way, but all the drivers—with the exception of Jacky Ickx and Vittorio Brambilla—were refusing to go out. Earlier, Jean-Pierre Beltoise had inspected the circuit on behalf of the Grand Prix Drivers Association and, unbelievably, found that the nuts and bolts holding many of the circuit barriers together were only secured finger-tight, with others not at all. Most of the drivers were in a militant mood and threatening not to race. In response, the organizers threatened both legal action for breach of contract and to impound the cars by locking the paddock gates, one at each end of the old Olympic Stadium.

After a night of bitter wrangling it was agreed that early on Saturday the teams would send out their own mechanics to help secure the barriers correctly. F1 was under contract and the show must go on. With the barriers secure, the one and only qualifying session began, Emerson Fittipaldi did three slow laps, pitted, then packed up and headed home as that had fulfilled his contract. The rest decided to carry on with Niki Lauda and Clay Regazzoni putting their Ferraris onto the front row. On the first lap scramble into El Angulo Brambilla, Andretti, Lauda and Regazzoni cannoned off each other, letting Hunt’s Hesketh take the lead. Soon Hunt spun on oil, and Andretti took over until his rear suspension failed. Thus Rolf Stommelen found himself leading in the Hill GH1, being chased by Carlos Pace’s Brabham.

On lap 26 tragedy struck. Cresting the brow at Rasente Stommelen lost his rear wing, the resulting loss of downforce catapulted the car into the barrier, just at the section his own mechanics had secured. Breaking in two, the car flipped over the barrier and tragically killed four marshals, along with motor racing at Montjuich forever. Rolf was still in the cockpit with his legs broken, and unbelievably it took another four laps before the race was stopped and a saddened Jochen Mass took his only Grand Prix win.

It’s unlikely that this spectacular circuit would have survived the modern requirements to stage a Grand Prix, but in its time it provided a unique challenge to the drivers and gave us many great races to reflect upon. We’ll let two-time Montjuich Grand Prix winner Jackie Stewart have the final word: “A fantastic circuit, a remarkable race track, one of the best. But safety was always going to be an issue there.”