Initially, motor racing in Great Britain was, in the main, a rich man’s sport, entertainment for the aristocracy and directly related to the “Sport of Kings,” horse racing. The Brooklands slogan, “The Right Crowd and No Crowding,” substantiates this idea that motor racing was the preserve of the wealthy amateur. However, the industrial revolution, two World Wars and the Depression did a great deal to evaporate the class system and its resultant social structure, not only in the UK, but mainland Europe as well.

Photo: Kary Jiggle

500-cc Racing

Just prior to the Second World War, a group of keen amateurs are attributed with the embryonic formation of the 500 Club—CAPA, to provide a low-budget form of motor sport. These enthusiasts were from the Bristol area of the UK—many also members of the Bristol Motor Cycle and Light Car Club (BMCLCC). Like last month’s profile car, a March, the acronym CAPA was formed from the initials of the founders—Messrs Caesar, Aldrich, Price and Adrian Butler. CAPA cars were based on the Austin Seven, mildly tuned, with most of the bodywork removed. Dick Caesar is thought to be responsible for suggesting motorcycle engines for these machines as they kept cost down, offered good speed, were readily available and yielded an ideal power-to-weight ratio. The whole ideology behind this form of motor racing was to be inclusive rather than exclusive; to keep wealth—which blighted the top end of the sport then and now—out of the equation of this new series of racing. A 500-pound minimum weight regulation and one gallon fuel capacity restriction tried to ensure true winners and champions would be crowned, irrespective of their social standing or background.

Photo: Pete Austin

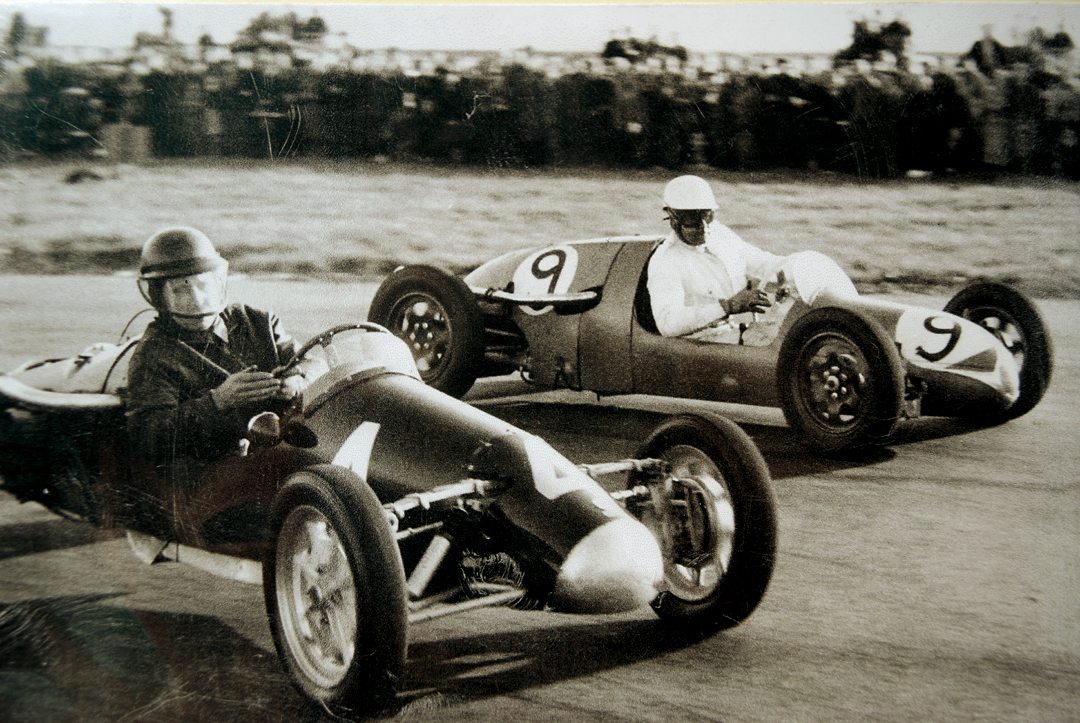

The outbreak of war in 1939 put everything on hold. The entire country was called upon to support the effort to rid the world of Adolf Hitler and his Nazi regime. However, a new club, the Bristol Aeroplane Company Motor Sports Club (BACMSC) was formed to keep the spirit of motor racing alive during the war- torn years. Following the cessation of hostilities, there was a return to a more “normal” life and the green shoots of motor sports again flourished, especially in this low-price series, now run under the banner of “The 500 Club.” Again, the same cost-effective ideology was embraced and individuals were encouraged to construct their own machines. Circuits such as Brooklands and Donington, commissioned by the War Ministry, were now “out of bounds,” and new venues appeared. Having said that, pre-war hillclimbs such as Shelsley Walsh were very much on the agenda, and competition was brisk. Spectator safety was a major cause for concern to the organizers to the extent that they even considered banning them from races. One committee member stated that if a number of spectators were killed while watching a game of football (soccer), football would simply continue, but if one spectator was killed at a motor racing event motor racing could be banned.

Photo: Pete Austin

Photo: Pete Austin

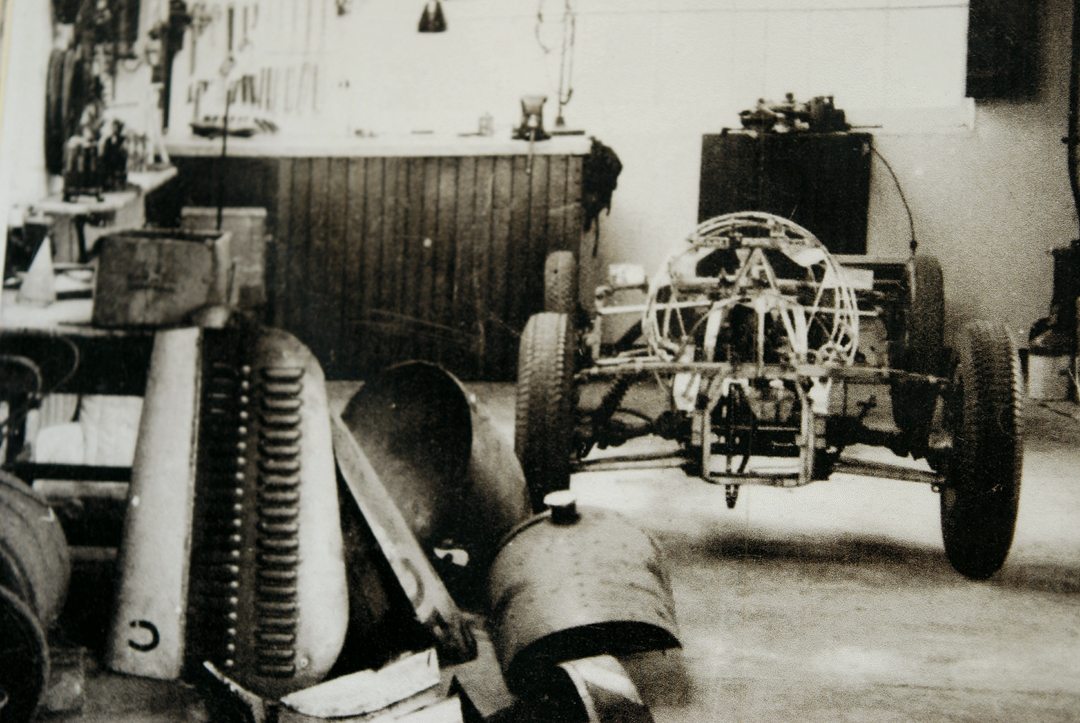

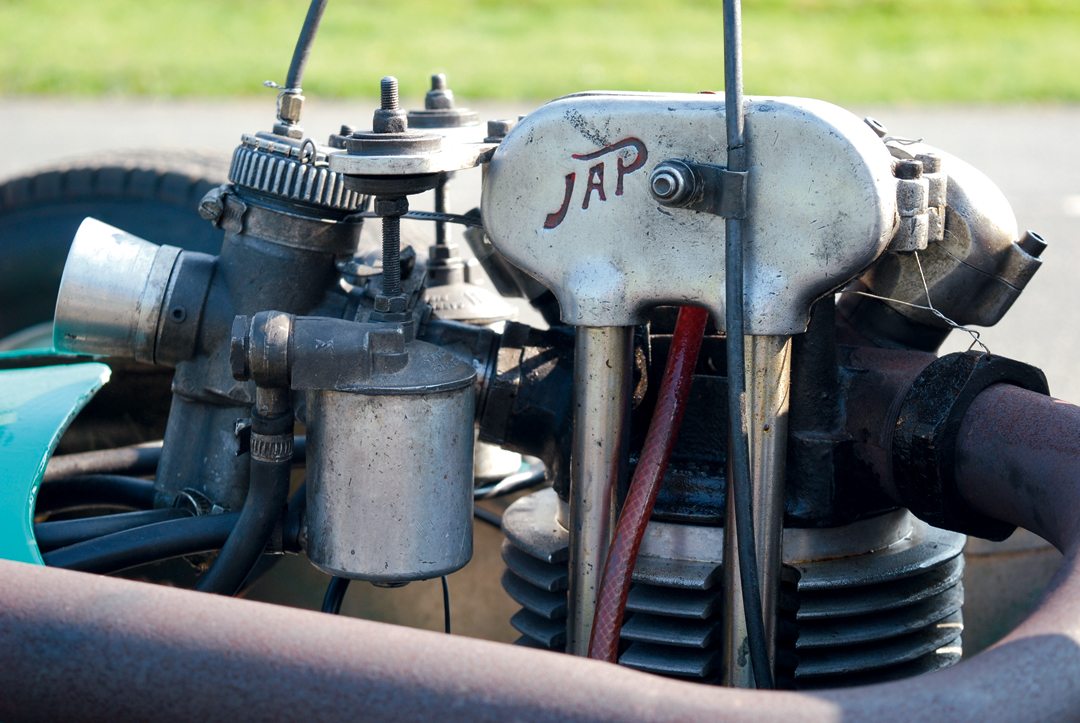

Cooper

Against this background, a certain Charles Cooper, a mechanic for racing driver, land speed record holder and Brooklands regular, Kaye Don, came to the fore, producing cars for his son John. The first car attempted was the pre-war T1 made to CAPA regulations based upon the Austin Seven. John was a very competent driver and was successful at all three disciplines of the sport—speed trials, hillclimbs and circuit racing, both at home and abroad. The Coopers operated out of their own garage premises in Surbiton, Surrey, as they would do for many glorious years to come. Post-war, chassis T2 was produced, and John assumed responsibility for most of the design and construction due to his father’s failing health. The car was quite fragile in design and built up from a simple ladder frame design marked out with chalk on the garage floor. It was powered by John Alfred Prestwich’s (J.A.P.) 500-cc motorcycle dirt track engine. These engines were designed in the 1930s and produced from 1935 to the mid-1960s primarily for speedway bikes where a strong and robust power unit was required with plenty of torque. Chain drive was through a Burman four-speed motorcycle gearbox and suspension via Fiat Topolino, all independent springs. Father and son managed chalk drawing to final build in just six weeks. R&D was ongoing, mainly at competition venues with many teething troubles to understand, repair and revise. A second chassis was built, the Cooper T3 for John’s great friend and former school chum, Eric Brandon, to compete as well. The 1946 season was composed entirely of hillclimb and sprint competitions, with both John and Eric regular podium visitors.

Photo: Philip Porter Press

One of the first UK post-war circuit races with 500s was held at RAF Gransden Lodge, an airfield in Cambridgeshire, on July 13, 1947, organized by the Cambridge University Automobile Club and the Vintage Sports Car Club. Period reports suggest the 500 race was “a bit of a shambles” as many cars mysteriously retired prior to the start of the race. Although John Cooper was a non-starter, Eric Brandon won the 500-cc, 10-mile race at a shade over 65 mph average speed in his Prototype Cooper T3, comparable to the four-liter Allard at 68 mph over the same distance. The 1947 season was a great year for Eric Brandon who outdrove his teammate, but this pairing put Cooper, as a constructor, firmly on the map, giving rise to the Cooper Car Company, which would go on to be a world beater and change the face of motor racing in the process.

Competition came from other drivers and marques with Colin Strang in his Strang 500, Frank Bacon in his FHB and Adam Butler in a Stromboli to mention a few. However, such was the demand for a Cooper that the first batch of 12 MkIIs was built during the 1948 season. They were an upgrade of previous models and cost £500 each. Of those first customers, a young Stirling Moss appeared with his money to purchase one of the new cars. Later that same year, he would be joined on the track by an equally youthful Peter Collins.

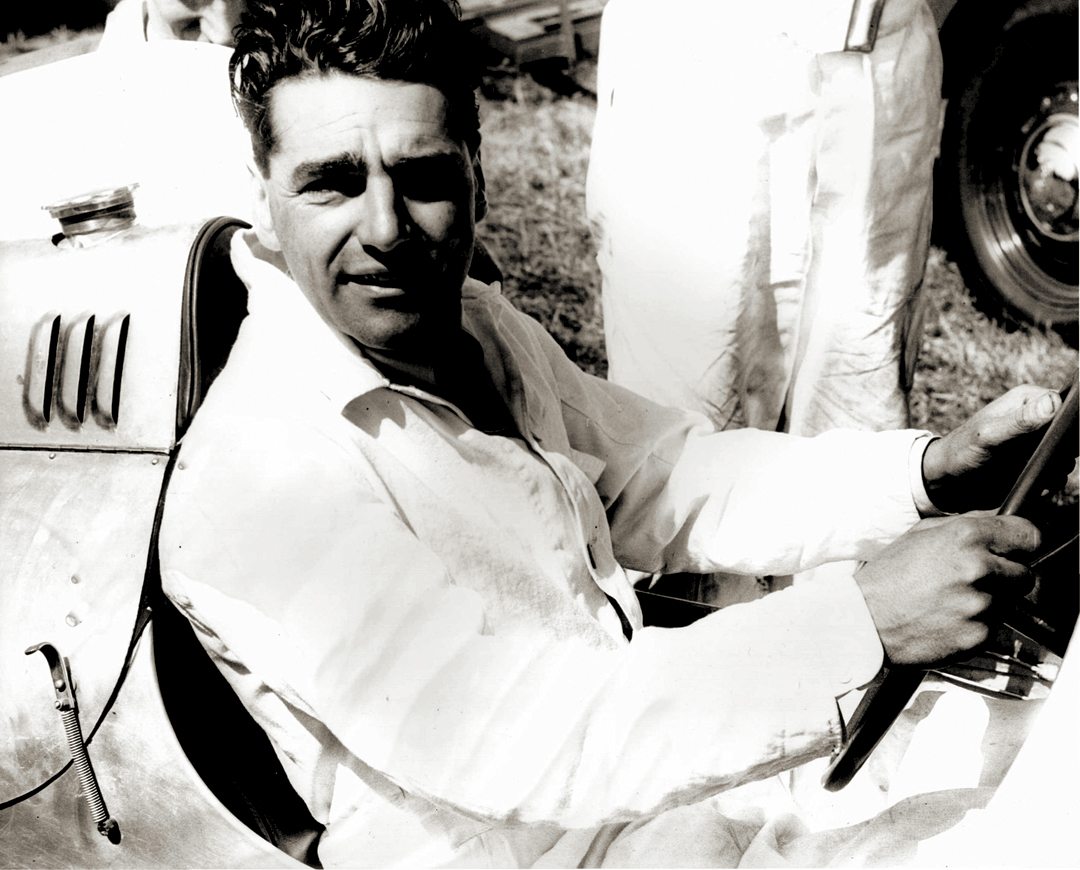

Young Moss

Moss had started his racing career in 1947, with his father’s BMW 328. Prior to that it was a stripped down Austin Seven around the fields of the family farm. While Moss’ father, Alfred, supported him competing in the BMW, it was a totally different matter when he learned Stirling had purchased a Cooper 500. However, thanks to some great father and son talking and bonding, the world’s most treasured racing driver was on his way with full family support. During two seasons competing with the MkII and MkIII Cooper-J.A.P. cars, the young Moss’ racing career flourished. For 1950, he was set on motor racing becoming a professional occupation, driving for HWM. He also wished to compete in the 500 series as well, and purchased the Cooper MkIV-J.A.P. we feature here.

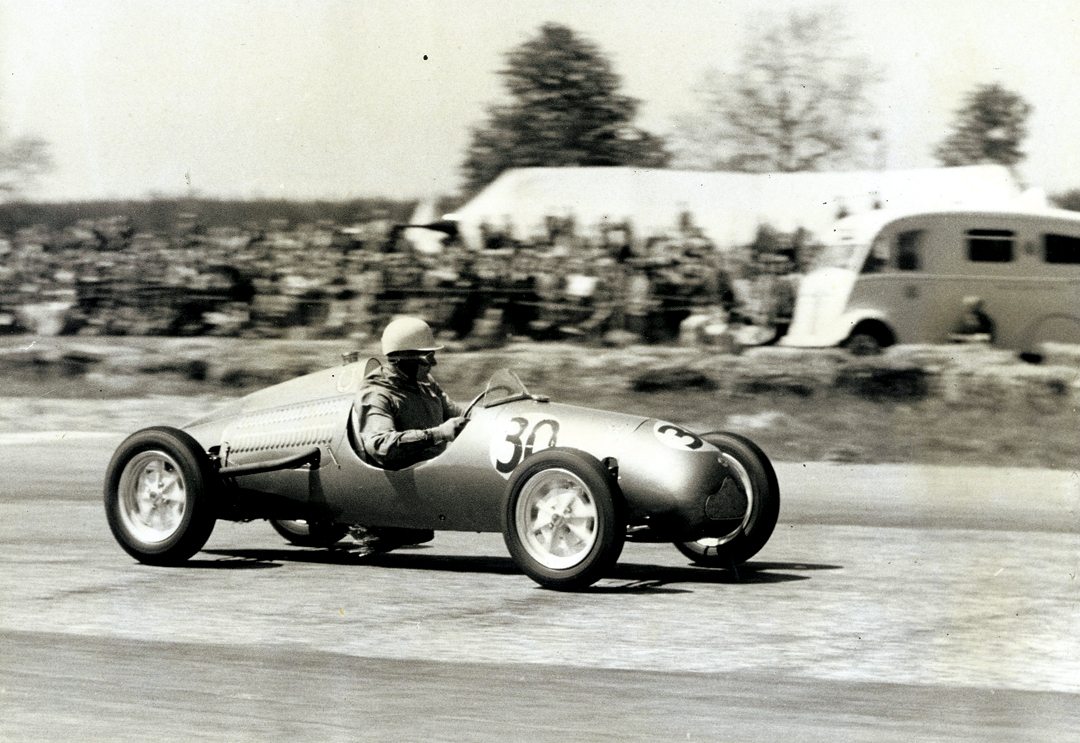

Racing these miniature Grand Prix cars was fast, furious and adrenalin-infused, with a cacophony of flat-out 500-cc motorcycle engines adding a soundtrack to the spectacle. Racing of 500s wasn’t confined to the UK, as many mainland European countries embraced the formula too, including Germany, France, Belgium, Italy, Switzerland and the Scandinavian countries. Further recognition came from the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA), when it adopted the UK 500 Club’s National Rules to create a new International Formula Three, for 1950. Additions to those rules included races to exceed 30 miles in distance and circuit lap distances of 1637 yards, or greater. Technical specifications required a necessary fireproof bulkhead, engines to be unsupercharged, a minimum dry weight of 440 pounds (without ballast), a minimum ground clearance of four inches and a free exhaust “not likely to interfere with other drivers.” This was the first time an International racing class had originated in the UK and, to a certain extent, put Great Britain on the world motor racing stage as it had a series of races set on the International Sporting Calendar.

Photo: Philip Porter Press

1950 Cooper MkIV chassis T12

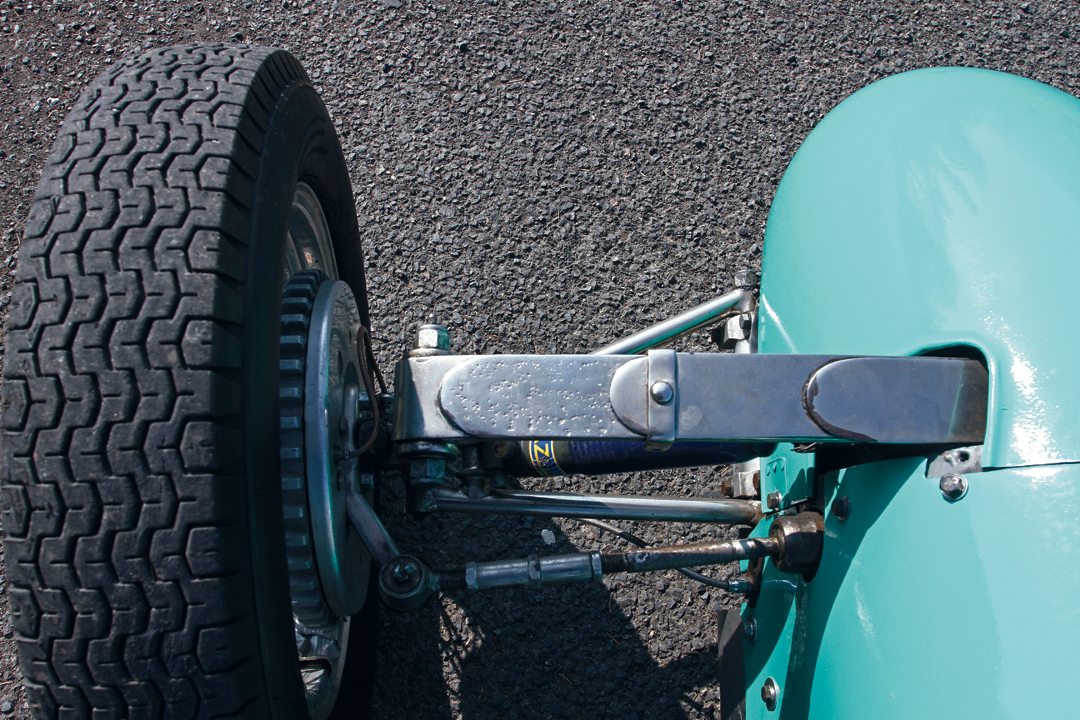

Cooper Cars Limited-designed chassis began dominating grids both in the UK and overseas. For 1950, two upgraded versions of the MkIII were produced, conforming to the new F3 regulations—the Mk1V, a T11 500-cc machine and a T12 that had the capability of being powered by a 500-cc, or up to 1,100-cc engine. The braking system for the car was either from an Austin A70 or Austin A40, vehicles that weighed something close to a ton. The Cooper-J.A.P., including driver, weighed little more than 700 pounds, so braking was very efficient. The system was split into two, with twin master cylinders allowing bias either to the front or back, whichever was more suitable to driver or venue. Unfortunately, the original concept of low cost, 500-cc racing was becoming a pipe dream. In those early “Bristol Boys” days of a racing car costing no more than £135 (including the engine) costs had dramatically risen with the onset of Cooper’s production models, which now exceeded £600 for each new car.

Photo: Ferrett Fotos

As with his MkIII Cooper, Moss ordered his new lightweight MkIV—believed to be one of only three ultra-lightweight versions made—with the mid-chassis section some three inches narrower than the norm. John Cooper and Ken Wharton were the other recipients. Additional extras for that certain “personal touch” included green anodized finish to the bodywork and a bespoke seat to mention just two. Unfortunately, his first race with the car at Brands Hatch, in April, wasn’t the result he was looking for. On the fourth lap, the piston seized and he retired. A month later and Moss was at Silverstone for the first of the International F3 races, which supported the landmark “Royal” European Grand Prix—attended by King George and Queen Elizabeth—the inaugural race of the modern Formula One era. Moss was hoping for better luck in the two races. Certainly he got his wish for heat one, his Cooper-J.A.P. not missing a beat as he crossed the line for victory with Wing Commander Frank Aikens, in his Iota, in 2nd place. In the second heat, Aikens got the better of Moss on the last lap. After 30 miles of dicing, Moss’s J.A.P. engine expired on the last corner, handing a 2.2-second victory to the Wing Commander. After a 7th place finish at the Grand Prix de Mons, it was off to Monte Carlo for the supporting F3 races, the first time Moss had visited the Principality. A disappointing first practice on the Friday led to concern about the performance, or rather the lack of performance, of his engine and was relayed to J. A. Prestwich. A new “sloper” engine was flown out to Monaco and fitted overnight, ready for the Saturday race, Heat 1. Although this new engine was no better, only revving to 5,800 rather than 6,800-7,200, Moss managed to use its torque and his driving ability to stay ahead and win. He also won the second heat the following day, beating Harry Schell and Don Parker into 2nd and 3rd places, respectively. Schell made history at the Grand Prix, as he changed engines and ran his car in the GP too—unfortunately failing to finish following an accident. Moss continued with the 500-cc J.A.P. engine for the next couple of months, with both good and bad results.

Photo: Shirley Monro Collection

Frustration grew race-by-race, the J.A.P. engine wasn’t delivering top-end power; wins came purely from Moss’ racing excellence. Pa Moss, mechanic Alf Francis and Stirling himself decided enough was enough and looked to change to the Norton “double-knocker” TT engine. That was easier said than done, though, as the Norton engines were few and far between, but persistence found the new power unit installed for the Silverstone 500-cc race at the end of August. Moss had developed a friendship with Swiss-born engineer Ray Martin who had his own garage business near Victoria Station, London. He had come to Moss’ rescue after it was found that the Norton engine required different mountings than the J.A.P. With just five days to go to the Silverstone race, Martin worked relentlessly to get it ready. Many off-the-cuff modifications were made, including welding onto the car an oil tank made from an old oil drum emblazoned with the name “Castrol,” when in fact the oil used was Shell. The new engine had been tuned and fettled by Harold Daniell and his assistant Hermann Meier. Having not driven the car, or even hearing it run prior to practice, pole position was well deserved in the new car/engine combination, but lady luck wasn’t with Moss. Minutes before the start of the race, the clutch seized. Left in the exhaust smoke and tire dust of fellow competitors, Stirling’s car was push-started by Ray Martin and Pa Moss. Established French Grand Prix racer and double Le Mans winner (1932 and 1933) Raymond Sommer was first away, with “Curly” Dryden leading after the first lap. A spirited drive let Moss blow away the opposition, taking the lead after about six miles, on lap two. At the end of the 10-lap race, Moss’ winning margin was seven seconds over Sommer, Alf Bottoms and Dryden.

Photo: Shirley Monro Collection

The second race meeting for the Norton-powered car was at Brands Hatch, the day after the prize giving for the RAC TT race, Dundrod, which was won by Moss in an XK120 Jaguar. As the Moss/Cooper/Norton combination took the flag for Heat 1, the crowd sang “Happy Birthday” in recognition of Stirling’s 21st. A rare driver error left the car needing gearbox attention as Moss retired from the final. A couple of weeks later and Cooper found out the hard way that “motor racing is dangerous.” The MkIV produced the first fatality for the Cooper marque as Raymond Sommer lost his life while competing in an 1100-cc Cooper MkIV in the Haute-Garonne Grand Prix, Circuit de Cadours, France, in September 1950.

At the end of the season, Moss’ car had competed in 23 races, with 12 victories, three 2nd places, two 6th and one 7th place, with five retirements. Moss had won the prestigious British Racing Drivers Club Gold Star, with his 500-cc results accounting for a good share of the points. He then decided to sell the Cooper, preferring to race a Keift 500 for the following two seasons.

Enter Charlie Graham

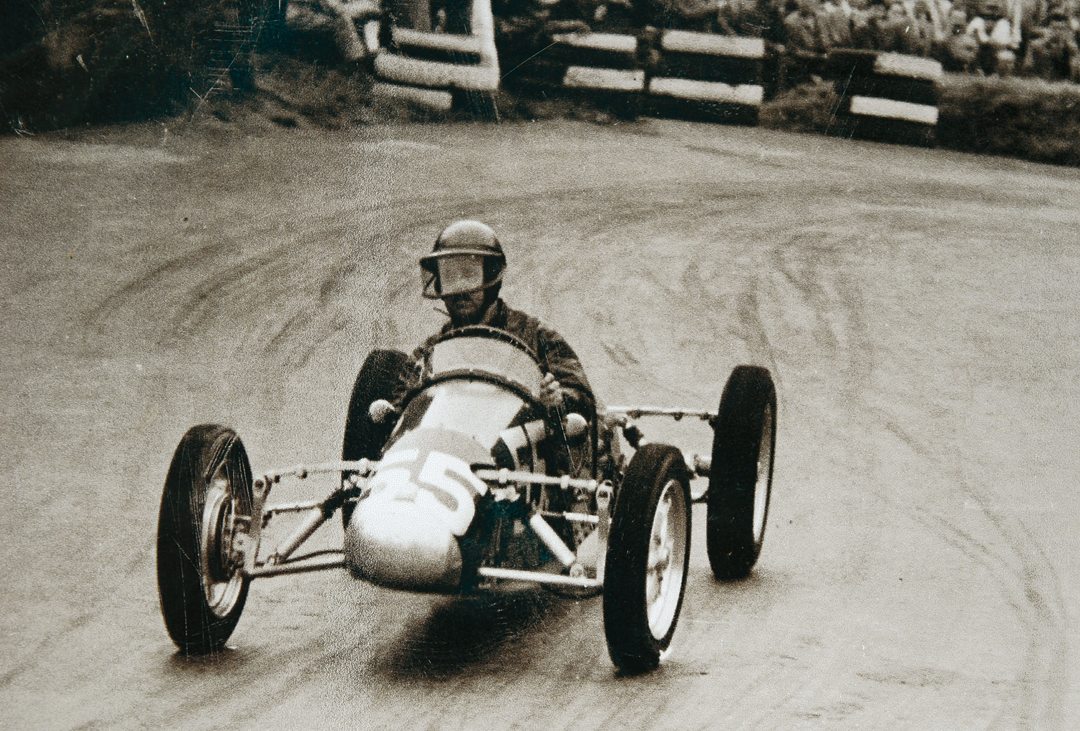

Charlie Graham, from Marharg, Dunfrieshire, Scotland, purchased the car from Moss and continued to race it much in the form as Moss had finished with it (other than the color) until the start of the 1953 season when the car underwent a significant modification. These modifications included lowering the car, replacing the fuel tank with a unit under the driver’s legs (George Wicken-style), and altogether making the car more sleek using semi-stressed bodywork. De Dion-style rear suspension replaced the existing; this was done in association with Joe Potts, a fellow Scot who made his own JP racing cars. A change in suspension would have a direct benefit to weight distribution throughout. Not only did Graham himself take on the whole venture, but his wife also lent more than a hand with the fabrication of the new bodywork—as can be seen in the photograph (right). As a former aircraft engineer, Graham thought his car needed extra rigidity through the bodywork, as the MkIV tended to flex more than the later machines that were then being developed. He also wanted the car to remain competitive for as long as possible.

Such were the modifications that it took very close viewing to appreciate its Cooper parentage. Graham, not a particularly keen Cooper fan due to the frosty reception he received when visiting the factory, wrote in the pages of Iota, the 500-cc periodical, “Messrs Cooper have no gripe at all even though one chops it up for firewood.” He seemed to hold the Cooper Company in some disdain by continuing, “It takes at least two letters to get an answer to a simple query for spares and, on my own visit to the works, the temperature around Ewell Road was at freezing point on a warm Summer day.” From this point forward, the car was entered as a Cooper Special.

Definitive races are pretty sketchy from this point, and are largely at venues in Scotland and Northern England with rare forays to Crystal Palace, Mallory Park and Oulton Park thrown in. Results vary from occasional wins and podium places to DNFs, but he was competing with a car that, although modified, was now considerably behind the design of then contemporary racing cars. The next custodian was Herbert “Burt” Stilborn, who purchased the car in 1956 and raced it through to the early 1960s, again mainly in the North of England. While no specific details are available, it is believed the car was still winning races, defying all logical thought given its age! The MkVIII and MkIX Coopers were far superior and in a different league, which speaks volumes for Graham’s modifications and his engineering ability.

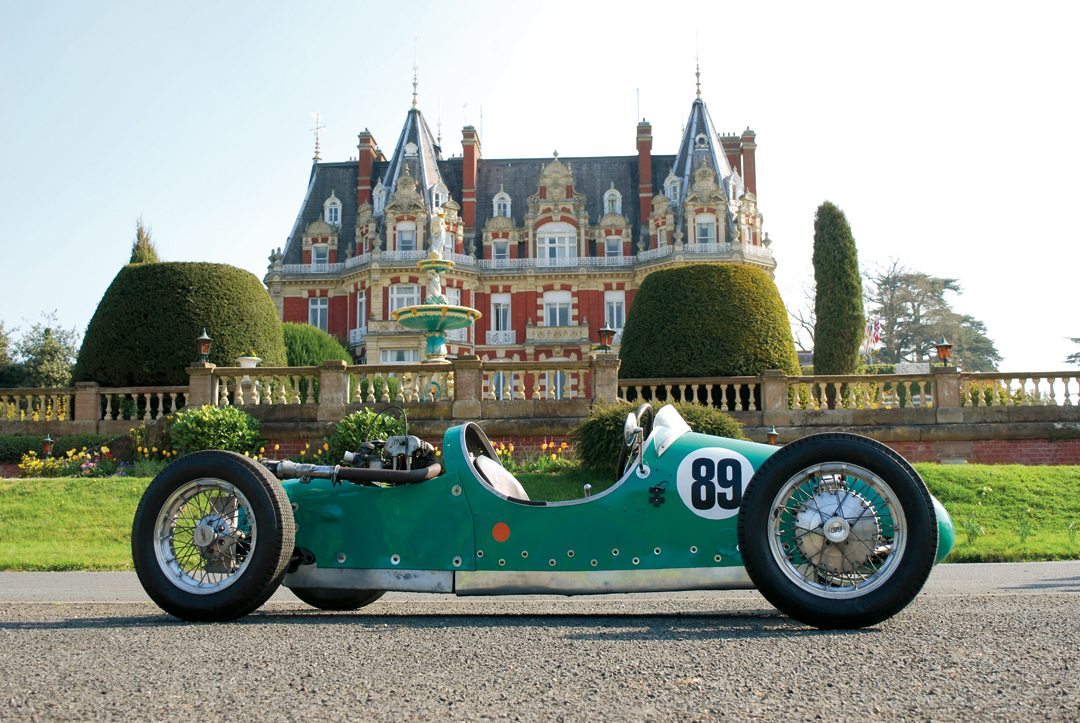

The present owner, Shirley Monro, purchased the car in 1991 from an enthusiast on the south coast of England. Over the intervening years, while the car remained with the low-slung Graham bodywork, the original Cooper suspension replaced the De Dion. Borranni wire wheels were the only other noticeable modification, these replacing the Cooper wheels fitted as standard. The car was complete with a J.A.P. engine with Norton clutch and gearbox, but now painted red. Shirley repainted the car in a turquoise blue livery, which it has kept to this day.

Photo: Shirley Monro

Driving the Cooper-J.A.P.

Our location for this test was the very picturesque setting of Chateau Impney, Droitwich, England, which was even more resplendent on a warm sunny spring morning under cloudless skies. The car looks absolutely immaculate in its turquoise livery, but preparation and starting this simply constructed racing car is very quirky and not the norm for formula cars. First we have to fuel the car with methanol. Average fuel consumption is 10 mpg. Methanol is used because of its cooling properties. This one-cylinder 500-cc engine produces a significant amount of heat that has to be dissipated, with no water to assist cooling and little to be gained from the total-loss oil system, fuel is the only solution, together with ambient air rushing past as you race. Both oil level and tire pressures are part of the systematic checks made by mechanic Bill Tull prior to any consideration of driving. The braking on this particular car is 80 percent to the front and 20 percent to the rear, to suit Shirley Monro’s driving style, but ideal for what is a very light vehicle.

As previously mentioned, the car is chain-driven through a Norton clutch and gearbox. Gearing is variable and is much dependent upon the venue. Today, the car is set with the ratios equally split. It has to be remembered the clutch is at gearbox speed not engine speed. We are to use the Start Line and straight of the Chateau Impney Hillclimb course. Much similar to that used for the speed trial events of the 1950s and ’60s, but deviating at Bridge Corner using the service road to continue left to a flick left and right through the chicane then following through a gentle left to the finish, climbing as we travel. Total distance is around half a mile. Not a thorough top-speed test, but ideal to observe the handling and balance of the car.

In today’s world, consideration has to be given at various venues to noise pollution. In unsilenced guise, the car will peak at 105db, but some venues insist on silencing down to 98db, or even 95db. This can be achieved, but the process exacerbates the aforementioned heating issues. Today, we’ll be running in unsilenced mode. Starting the car has modern day issues too, this time Health and Safety, external starting mechanisms are frowned upon by organizers as are running wheels and chains in a closed environment, i.e., an open pit garage is considered too dangerous. So, it’s a push start for us.

First, to climb aboard this thin, cigar-shaped vessel, suspended by leaf springs attached to four motorcycle-type wire wheels. Put your left foot into the cockpit while resting your backside on top of the bulkhead directly behind the driver seat. With hands each side of your buttocks, bring your right foot into the cockpit. Continue by moving your hands to a mid-cockpit position gripping the left and right bodywork of the sides of the cockpit. Then, supporting your body weight with your arms, carefully thread your legs forward toward the footwell and pedals, while lowering your body onto the seat. We’re in! Although quite tight for lower body parts, the low cockpit sides gives room for plenty of arm and shoulder movement and allows a certain freedom to move to both the left and right with your upper torso. Looking forward, the three-spoke Cooper steering wheel takes up all the width of the crudely constructed metal dash that has an equally crude rev counter to the right and two simple switches to the left—far left, a switch for mandatory fog lights and, between that and the central steering column, an engine kill switch. To the far, bottom right, almost resting on your right leg, is a large red oblong pull switch with the word “FIRE” hand written in white—obviously the fire extinguisher pull. There are two levers in the cockpit, situated for easy operation, on the left an inboard hand brake and on the right the gear stick.

Now, that starting…the J.A.P. engine fitted to our car has a high compression rating of around 14.2:1 (these engines can range from 13.5:1 to 15:1). Without any mechanical pump we have to get fuel into the system—no fuel, no start. The running engine feeds fuel mechanically, but to start, the car has to be rocked back and forth while in first gear until we’re on compression and a spray of fuel can be seen squirting from the carburetor. With the clutch out, it’s a push start—but don’t touch the gas pedal! That’s unless you wish to see your helpers flat on their faces having pushed you away. The car fires up with a great staccato bark and we allow it to come to temperature—no gauges, just a feel with the hand that the engine is warming. Once warm, the signal is to go. Foot on the throttle and the car is away, great power and torque from the J.A.P. engine. Along the straight first, second and third gears selected almost one after the other, into top by the time we get to the left-hander, but down to third for the flick left and right, steering the car with the throttle too—a great sensation as it dances through the chicane. Back up to top gear we finish the run. Just a few short minutes, but a real adrenalin-fueled experience. A second and third run gets one comfortable with the eccentricity of this great little car.

Driving a 500 is so different to any other formula car. It’s hard into a corner, keeping on the gas where others would be braking due to the lack of a differential being fitted. Without a differential, if you don’t drive into a corner you’ll understeer and go straight on, you have to promote oversteer by hitting the throttle hard and turning in hard. Once oversteering, you now correct the slide by steering out. Fitting a differential would compromise the speed of the car, especially in corners where one of the rear wheels, dependent on it being a left- or right-hand bend, would be off of the ground and you’d lose traction and speed. Cars with a differential would be taking a completely different line at this point. In fact, there were many accidents and disasters in VSCC and other Formula Libre races where 500s were mixed with other machinery. Today, in the main, 500s now have a race purely for that type of car. On the straight, the car is very stable on level surfaces, but any camber or undulation will steer the car one way or another, so, like cornering, it’s full concentration—you’re on the edge, get it wrong and you’ll definitely fall off. Get it right and that warm sense of achievement feels so good. Some have compared it to riding and taming a wild horse.

Conclusion

This little Cooper-J.A.P. is no doubt a forerunner of the contemporary racing cars of today. In period, it was a light chassis, powerful engine full of torque and drive that delivered a top speed capable of beating the opposition. Nothing has changed, engineers look at weight saving measures—carbon fiber came to the fore in the 1980s together with turbocharged engines to give a power advantage. In whatever form of motorsport, we still chase that same dream. Of course, there were no gadgets, computers or electronics in the 1950s, just pure driver ability and car performance to win the day.

Sir Stirling Moss regards the purchase of the Cooper MkIV-J.A.P. as, “… a pretty good investment because it carried me to victory in the prestigious Monaco Grand Prix supporting race.”

It is clear from our findings that an opening paragraph from a piece written in The Motor magazine in the late 1940s, by Dennis May, was completely right. In his column, “Dennis May Introduces John Cooper” he writes: “When, in some decade yet unborn, posterity busies itself with a genealogy of the mechanical bacteria men called 500s, the chronicle of the Early Days will be replete with references to a gormful young Surbitonion called John Cooper. It will bracket his name with two others: Charles Cooper, John’s father … who collaborated at every stage of the design, construction and development of the 500-cc Cooper-J.A.P. sprint cars: and Eric Brandon, John’s close friend from knee-pantshood …”

Motor racing owes a great debt to many stalwarts and pioneers of our sport from the beginning through to those burgeoning post-war days when it grew to unimaginable heights and beyond. Small businesses such as the Cooper Car Company grasped the vision and responsibility of ongoing design and development of the formula racing car. Cooper was indeed a prime mover, and the MkIV T12 was a small step along the way to them ultimately becoming World Champions.

SPECIFICATIONS

Overall Length: 115 inches

Overall Width: 51 inches

Wheelbase: 87.5 inches

Front Track: 50 inches

Rear Track: 46 inches

Wheels: 5.00 x 15 front & 5.50 x 15 rear

Tires: Dunlop (as per regulations)

Weight: 510lbs (Fully fuelled with 3.5gal)

Engine: 500-cc Speedway engine

Gearbox: Norton AMC

THANKS/RESOURCES

Stirling Moss – My Cars by Doug Nye

Stirling Moss – All My Races by Alan Henry

A-Z Formula Racing Cars by David Hodges

Cooper Cars by Doug Nye

Cooper by Mike Lawrence

Stirling Moss Scrapbook 1929–54 by Porter Publishing

Autosport and Motor Sport periodicals of the era.

SINCERE THANKS TO:

Shirley Monro for the use of her car. Bill Tull and Jan Nycz for their mechanical support and insight into 500 racing. Rod Spollon for making the Chateau Impney venue available to us. James Ashe of We Are Alias PR for co-ordinating the day.