Automobiles Martini tasted success in the French Formula Three Championship on a regular basis. Race wins and championship success were commonplace for cars designed and manufactured by “Tico” Martini and his loyal team. Race victories around the streets of Monte Carlo were common too, with the most important Formula Three race in the world being won 10 times by a Martini. The 1982 MK37 is one of those winning designs.

CONTINUING THE WINNING WAYS

Martini Formula Three cars were winners, and everyone involved in French motorsport wanted it to stay that way. Each year, when a new Martini MK chassis was launched, the question asked was, “Can it win at Monaco?” In those days, the Monaco F3 race was the race to win, more important than any single championship success and it was a race that Martini cars were very good at winning.

Photo: Mike Jiggle

Success for the marque, around those famous streets, started in 1973 with Jacques Laffite, and by the time the MK37 arrived for the 1982 season, Martini had won the big race five times. The Martini MK37 would be the mainstay of the French Championship, although ultimately not a championship winner! In the European Championship, the car was also destined not be a championship winner, but it would fill three of the top six places and, around the streets of Monte Carlo, it would also be a winner. Alain Ferte and Philippe Alliot finished 1-2 in their Marlboro Martini MK37-Alfa Romeo cars, crossing the line ahead of the driver who would eventually win the 1982 European championship crown, Oscar Larrauri.

Designed by Tico Martini, the MK37 was a car of the ground-effect era, and it is fair to say it was not the most loved car of this period. It was workmanlike and completed the job, but many felt it was not a thing of beauty. A complicated suspension configuration, wide sidepods and a narrow nose made for an ungainly looking vehicle. But it could win races!

In the French championship, Michel Ferte, driving a Total-backed car for the Oreca team, lost out to Ralt RT3 driver, Pierre Petit, driving for Dave Price Racing at the end of the season. Petit was the original owner of the MK37 profiled here, but ended up racing both Novamotor and VW-powered Ralts during the season. Following Ferte in the point standings were a number of MK37 cars, driven by Francois Hesnault, Patrick Gonin, Philippe Renault and Pascal Pessiot. Philippe Huart, Patrick Teillet and Guy-Leon Dufour also recorded point-scoring finishes with their examples. Eight of the top 11 cars in the final championship standings were MK37s.

In the European Championship, Oscar Larrauri and Emanuele Pirro tied up proceedings in their Euroracing 101-badged March 813 cars, with Alain Ferte taking 3rd in his Automobiles Martini Oreca-entered MK37. Didier Theys was classified 5th with his MK37, and Philippe Alliot 6th. Interestingly, the only Ralt RT3 in the top six, considering its total domination in Britain, was placed 4th, driven by James Weaver.

Our MK37 featured here played an important part in helping one of France’s finest Grand Prix drivers recover from a near fatal accident, and has subsequently changed hands several times. With Philippe Gache at the helm, it won around the streets of Pau in a Historic F3 race in 2008, and has most recently been raced in its country of origin by Bruno Lambert. The car now resides in the UK with a new owner, and is about to embark on a season of competition both in Britain and Europe.

MARTINI BY DESIGN

Renato Martini, nicknamed “Tico,” was born on December 6, 1934, in Pigna, Italy, although he grew up in the Channel Islands on Jersey. Passing his driving test at the age of 17, Martini’s father, a headwaiter at a hotel, presented him with his first car, and this vehicle started a love affair with motoring that continues to this day!

Returning to Italy to work at an Alfa Romeo franchise in 1952, Martini was persuaded by his father to return to Jersey a handful of years later to join him in the hotel trade, and during this brief tenure Martini decided to enroll with the local automobile club and drive a car in his first race on the island’s sand.

Shortly after his competition debut, Martini was employed by a friend, Bill Knight, to become the head mechanic at a local kart track, and very soon afterward the first Martini-manufactured car was born. Using a Triumph motorcycle engine, Martini guided his little machine to victory in the Bouley Bay hillclimb in July 1961.

His friendship with the Knight family paved the way for Martini to move to the Winfield School at Magny-Cours, where he started building cars in the garage, at the track. His cars would be badged with type numbers MW for Martini-Winfield and then MK for Martini-Knight. The MW1 F3, powered by a Ford, appeared and was followed by the MW3 before the first MK labelled car was made ready for 1969. The MK5 won the marque its first victory at Nogaro in the hands of Jean-Pierre Jassaud, and with that initial success being scored, car sales soon followed.

Photo: Mike Jiggle

In 1973, the MK12 proved to be a real winner, scoring victory in the French championship and at Monaco for Jacques Laffite. For the next few years Martini, decided to concentrate on Formula Renault, but he returned to F3 for 1977 with the pretty MK21 with which Didier Pironi triumphed in the Principality.

Martini domination in the Monaco F3 race wasn’t far away. The MK27 won with Alain Prost driving in 1979, the MK31 with Mauro Baldi in 1980 and the MK34 with Alain Ferte in 1981. The MK37, the car type profiled here, won the race in 1982 with Alain Ferte at the wheel to score his second Monaco triumph. Martini cars would win the race for the next four years, as well. Michel Ferte completed a hat-trick for his family by winning in 1983 with his MK39, while other victories included: Ivan Capelli in 1984 (MK42); Pierre-Henri Raphanel in 1985 (MK45); and Yannick Dalmas in 1986 (MK49).

Martini also achieved some degree of Formula Two championship success, though sadly the Formula One dream was not so successful, but cars built by Tico Martini continued to win countless races and many French national championship events. In 2004, Guy Ligier acquired a majority shareholding in Automobiles Martini, and took over control of the company. The friends decided to work together, and the Martini name lives on with the company Ligier-Martini. Today, if you call in at the factory in Magny-Cours, you will find Tico working on his latest project.

Photo: James Beckett Collection

THE PIRONI LINK

Didier Pironi was fast and he was a winner. Born in 1952, Pironi liked cars and when he was old enough, he followed his half brother, Jose Dolhem, in attending the Winfield School. Dolhem’s own racing career was short-lived, two non-qualifications and a non-finish for Team Surtees during the 1974 season his only records of note, while his younger sibling had greater things in store. By winning the Pilote Elf competition in 1972, Pironi was guaranteed progression into full-time racing, which in turn led him to a French ladder series, notably Formula Renault.

With Elf funding, Pironi quickly became a race winner. His speed on track helped him make a name for himself, but despite the disappointment of suffering car problems on and off for two years, by the start of the 1977 season he was ready to make the jump to Formula Two.

The Martini/Elf team, managed by Hugues de Chaunac, with a Martini MK22 designed by Tico Martini, was destined to be one of the “weapons of choice” in the European championship of ’77, and lining up alongside Rene Arnoux, Pironi and the team entered the season with high hopes.

Photo: James Beckett Collection

For Arnoux, the season started well with victory at Silverstone in the Daily Express International Trophy meeting, and although he failed to finish Round Two at Thruxton, another win in the following event at Hockenheim set him well on the way to title glory. For Pironi, three non-finishes in the opening three races were far from ideal, and the failure to score points in those races ultimately prevented him from winning the title. Pironi did achieve six podium finishes, including a victory at Estoril, but at the season’s conclusion he was placed 3rd in the drivers standings, behind teammate Arnoux and the Project 4 Racing Ralt-BMW of Eddie Cheever.

One memorable moment for Pironi and Martini did occur during the 1977 season, with it ironically being the only F3 appearance of Pironi’s career. Driving a Martini MK21 for the Ecurie Elf team, Pironi barnstormed his way to victory around the streets of Monte Carlo to win the prestigious Monaco F3 race. Interestingly, the following year, with Elf support, he graduated to Formula One with Elf Team Tyrrell, scoring seven points from five top-six finishes. Victory was also achieved at Le Mans with the Alpine Renault team.

Remaining with Tyrrell for 1979, Pironi scored podium finishes in Brazil, Belgium and the United States, with 10th in the title race being his end-of-season reward. On the verge of true F1 stardom, Pironi joined the iconic French Equipe Ligier Gitanes for the 1980 season, and in the fifth race of the year the Frenchman was able to call himself a Grand Prix winner.

Photo: James Beckett Collection

Pironi continued to race for Ligier before moving on to Ferrari where he would score more wins and even become the championship leader going into the 1982 German Grand Prix. Leading the table with 39 points, Pironi was in a strong position to become France’s first World Champion, but a crash during practice ended all of that. With bad visibility on a rain-soaked track, Pironi plowed his Ferrari into the back of Alain Prost’s Renault while trying to overtake the Williams of Derek Daly. He suffered horrific leg injuries in the crash, and many thought it impossible that Pironi would ever again climb into a racing car. But climb back into a racing car he did, and it is here that our Martini MK37 plays its part! The car was owned at that time by Jacky Setton, the importer of Pioneer electronic products into France. Setton offered up the Martini to his good friend as a vehicle for the racer to reacquaint himself with single-seater driving. At a number of locations, Pironi spent time in the car to teach himself, once again, the techniques of racing, and his performance in the Martini led him eventually back to a Formula One car for a test session. A call from the AGS team followed and Pironi flew to Paul Ricard to drive the team’s new AGS JH21C. The car was basically a modified Renault RE40 monocoque equipped with a Motori Moderni V6 turbo from the stable of Carlo Chiti. The French press was enthusiastic about a “comeback” but this test was really a public relations exercise, although a later test in Rene Arnoux’s Ligier at Dijon was a more serious affair. Pironi’s lap times were not far off those posted by Arnoux, but for some reason a deal was not struck and despite our Martini helping Pironi to regain his pace, he was not to be seen in a racing car again.

The following August, while competing in an Offshore Powerboat race called the The Needles Trophy, near the Isle of Wight in England, Pironi’s boat “Colibri” was involved in an accident. Hitting the wake of a nearby tanker vessel, Pironi’s boat was sent crashing. Along with fellow crew members, former Ligier staff member, Jean-Claude Guenard, and two-time Paris-Dakar winner Bernard Giroux, Pironi was killed instantly.

TEST DAY

Monaco it may not be, but Blyton Park near Gainsborough in Lincolnshire, close to RAF Scampton, home of the famous “Dambusters” 617 squadron during World War II and now the home to the world famous Royal Air Force aerobatic team “The Red Arrows”, made for an enjoyable venue to put the Martini through its paces.

On first approach, the Blyton venue seemed to be a ramshackle affair, an old airfield road being the main entrance leading across arable land toward the buildings that now form the hub of operations. However, it was easy to imagine what the former airfield was like in its prime. RAF Blyton opened in 1942 and the airfield began life as an Operational Training Unit (O.T.U.) for Polish flyers, before becoming home to 199 Squadron and a fleet of Wellington bombers. For the rest of the war, Wellington and Lancaster crews flew from Blyton on sorties over Europe, and like so many airfields in the UK, the gates were closed for operational flights during the 1950s. Enough of the old runways survived the following years to allow the track that is present today to take up residency.

A large barn and a series of smaller buildings, including a new clubhouse pavilion, made a welcoming sight on a grey day on which heavy rain had been seen tumbling from the sky almost from the first minute we had set off for Blyton.

A warm greeting from the staff of Neil Fowler Motorsport put everyone in a good frame of mind ahead of the day’s action, and it was interesting to see that the MK37 was not the only car in action at Blyton. Neil Fowler Motorsport had exclusively hired the facility for use by a number of their customers, and on track alongside the Martini could be seen a pretty little March Formula Two car, a handful of Formula Ford 2000 machines and a rapid Caterham 7.

Before I was offered the chance to climb aboard the Martini, I was able to sample the Blyton tarmac in the STP-colored March, and these laps allowed me to familiarize myself with the twists and turns and long back straight that Blyton offers.

Much used by professional teams looking for “somewhere a little bit different,” it is not unusual to see British Touring Car Championship teams or a squad from the FIA World Endurance Championship in action at the venue. Tucked away from prying eyes, Blyton offers these teams wonderful seclusion for a secret test or two. Indeed, the day before our visit, a well-known WEC team had been present for some night testing and video filming. The Blyton people had even dampened the circuit to allow the track to look like a rain-soaked Mulsanne for the footage!

We didn’t need the track to have water added to it, as the rain was lashing down as I steered the March around the circuit. The F2 readily lapped up the track, and I smile as I reflect now thinking that on this occasion a Formula Two was actually a warmup to the main event of the day, a Formula Three car. Normally it is the other way around!

Returning the March to the indoor paddock area, I could see the Martini MK37 waiting for me. Fresh from two days of testing a Dallara F308-Fiat at the Adria International Raceway in Italy with Vincenzo Sospiri’s EuroNova Racing, I was keen to see how a 1982 F3 car would compare against its current cousin. Current F3 cars are covered in aerodynamic aids. The wings on a Dallara F308 may not look big, but boy do they deliver some mechanical grip. The Martini was not about to offer me the same type of aero, but it did carry wings, and it came from an era of ground-effects—although Classic F3 cars do not race in this configuration now.

HEADING OUT ON TRACK

Climbing into the car I found its cockpit larger than its rival from 1982, the Ralt RT3, which I was able to sample at Brands Hatch a few months earlier. In comparison to the March Formula Two I had just climbed out of, I was pleased to feel that I had more room around the pedals for my feet—although there was no comparison with the “feet in the air” style of the Dallara I had driven just days before!

Strapped into the car by Neil Fowler, I settled myself before tugging once more on the shoulder straps to ensure I was held tightly in place behind the wheel of the Martini. We had not enjoyed the time and luxury of making a specially molded seat for the car prior to my driving of it, and my experience tells me that it is near impossible to gauge feedback from a single-seater when not sitting comfortably.

With the steering wheel clicked back into position on the steering column, I reached for the starter button to fire the car’s two-liter Alfa Romeo engine into life. A quick press and the Martini fired, and a couple of blips of the throttle gave that reassuring bark of the exhaust that makes an F3 engine so recognizable.

Selecting first gear, and letting the clutch out, the Martini moved forward—no stalls, unlike my first attempt to roll the RT3 forward at Brands! Heading out of the Blyton paddock area, I drove the car toward the entry road and out onto the circuit.

My first two laps in the Martini were behind our photography vehicle, so I was able to acclimatize myself to the French machine at a relatively slow speed for a couple of tours. Once the photographs were in the can, I was waved past to undertake my test.

Accelerating across the Blyton start/finish line, the Martini felt happy to be unleashed from behind the photo car and I was able to turn the car tightly through the opening left-hand corner, called Jochen. The car’s wet-weather tires offered a great deal of grip as I got more aggressive with the throttle. The rear of the car hardly moved as the power came in, and as I increased the revs out of the left-handed Lancaster corner along the back straight, I was able to pick up speed before having to double declutch down the Hewland gearbox for a tight left-right corner that formed the Wiggler chicane.

Exiting the chicane, the track curved to the left again and the Martini responded keenly as I accelerated and pressed on toward the next left-hander, Bishops, and the following turn called Bunga Bunga. A high-speed right and left kink at Port Froid took me at considerable speed to a right-hand bend called Ushers and the final turn, Twickers, which returned me to the start straight. Now confident in the car around the circuit, I set off on another lap at greater speed.

Avoiding the temptation to literally jump on the throttle as I had been used to doing with the Dallara in Italy, I pressed firmly to bring the power in more gently and in an attempt to explore the handling characteristics of the MK27 fully. In period, these cars may not have scored multiple race wins, but their success certainly did come on demanding circuits such as Monaco and Magny-Cours. Both of these tracks are not about out and out speed, marking the MK27 as a solid performer on tracks where good handling is sometimes more essential.

From my time in the car I am able to relay that it felt very solid beneath its wheels. Admittedly, I was not at peak speed on a fast circuit such as Silverstone or Spa, but in the damp conditions of a winter’s day in Lincolnshire, the Martini felt every bit as good as the Ralt RT3.

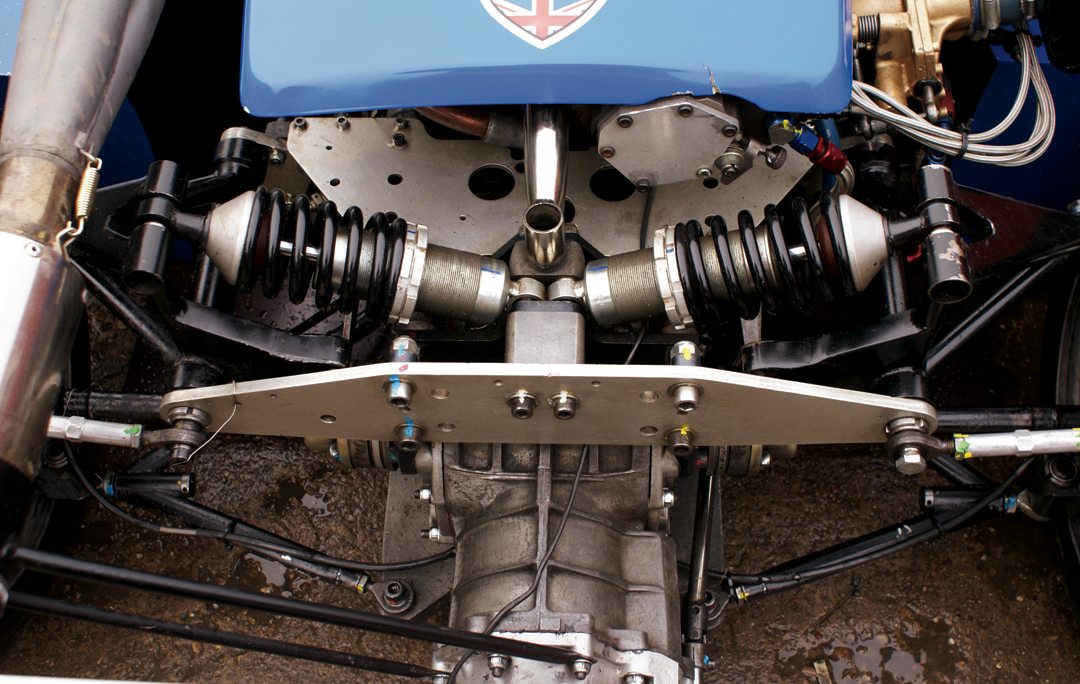

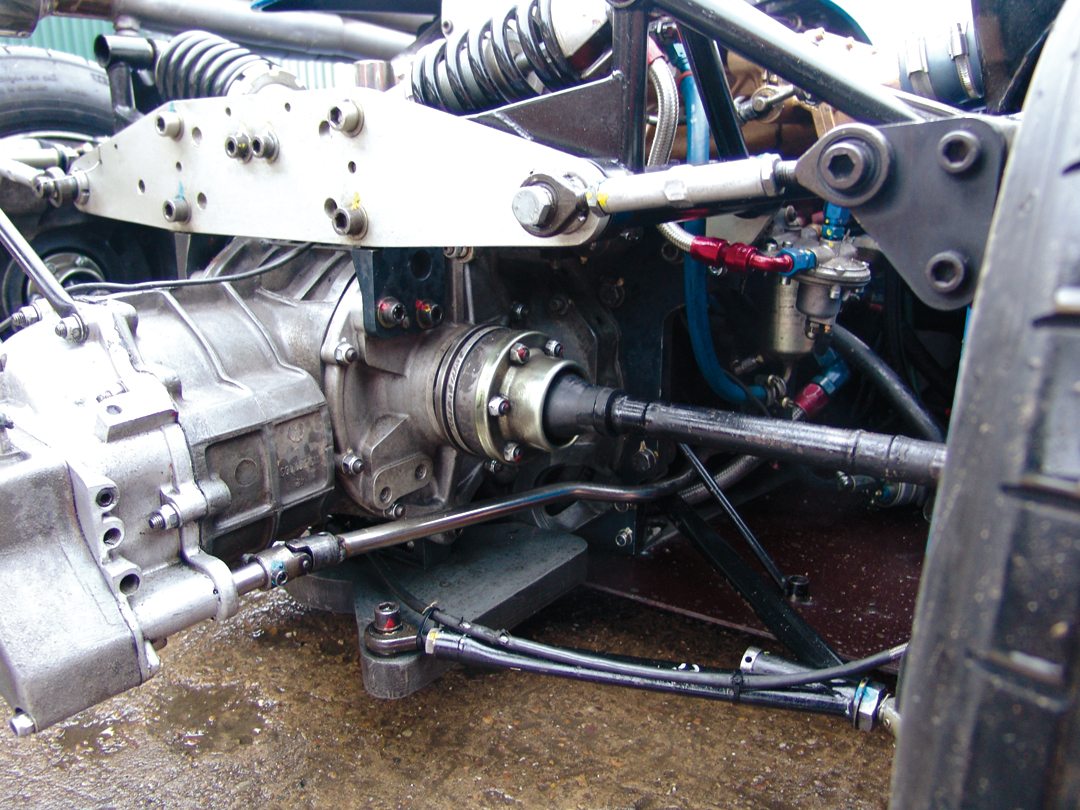

The Ralt RT3 enjoyed huge category success, Ron Tauranac’s car was a revolutionary design that was a game changer for Formula Three. The Martini MK27 was not, and Tico Martini was forced to work hard to stop Ralt ruling the F3 roost. The MK37 had a lightweight aluminum monocoque and a very narrow footprint, with ground-effect sidepods on either side of the car. A problem it encountered at the time was in the suspension department, mainly because of parallel links with dampers mounted on brackets above the gearbox.

At the front of the car, the MK37 used top rockers and lower wishbones. Around the streets of Monte Carlo these helped make the car feel very stable I am told, and in my short experience I felt that as well. Blyton proved to be an ideal venue to drive a car such as this, as its true handling could be felt. Short straights and continuous corners allowed me to accelerate, brake and turn and the Martini responded readily.

The brakes were firm and sharp, with no hesitation, and on acceleration the gear lever was ideally placed for me and allowed the ratios to mesh without any problems. Downshifts were equally trouble-free. Pulling too many revs was never going to be an issue for me on a track like this in conditions that were far from ideal, and so my test was more of a controlled high-speed drive rather than a full-speed unabated blast.

I can confirm that Tico Martini certainly knows a thing or two about making good handling racing cars, and this in my experience seems to be one of them. In total, Martini manufactured 17 examples during the 1982 season, with this car carrying the designation of chassis number 11.

Before long my moment was up and it was soon time to drive the Martini from the track and into the paddock area. Switching the car off, I must admit I was sorry to have to get out. Back in 1982, the year this car was built and raced, I had a Didier Pironi “Haribo” sticker attached to the headboard of my bed! Now, all these years later I had been able to drive the very car that had allowed Pironi to return to the track in an attempt to restart his career from a crash that had very nearly killed him.

I have been a lifelong F3 fan and have travelled the length and breadth of Britain watching F3 races for more years than I am almost able to remember, and in that time Martini cars have always been a rare sight. They were in period, and they still are today! Martini F3 cars traditionally spent their careers in France. Although they enjoyed success in their homeland and in blue-ribbon events, such as the race at Monaco, they only appeared in Britain occasionally when the European Championship visited. If British F3 teams had been convinced back then to run these cars, I wonder how much more successful they would have become? Would Martini have managed to break the mold and become a truly international F3 championship-winning marque? We will never know, but I can’t help thinking that the answer to that final question is yes.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: Aluminum monocoque

Wheelbase: 2465mm

Weight: 465kg

Engine: Alfa Romeo 2-liter inline four (other engine options available)

Gearbox: 5-speed Hewland MK9 with Martini casting for rear casing

Suspension: F – Upper rocker and lower wishbones; R – Parallel links with top-mounted dampers

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS / RESOURCES

The author would like to thank Robert Tusting for his kindness in granting us permission to drive his Martini MK37. Thanks also go to Richard Usher of Blyton Park for allowing Vintage Racecar to use his facility for the testing of the car, and to Rob and Neil Fowler of Neil Fowler Motorsport for their help in making everything possible. As ever, thanks go to John Pearson for his driving of the vehicle used for the “car to car” photography sessions, and further thanks to Colin Beckett and CJB Media for providing race programs, race results and F3 documentation. The Automobiles Ligier-Martini staff also helped with information shared via data on their official website.