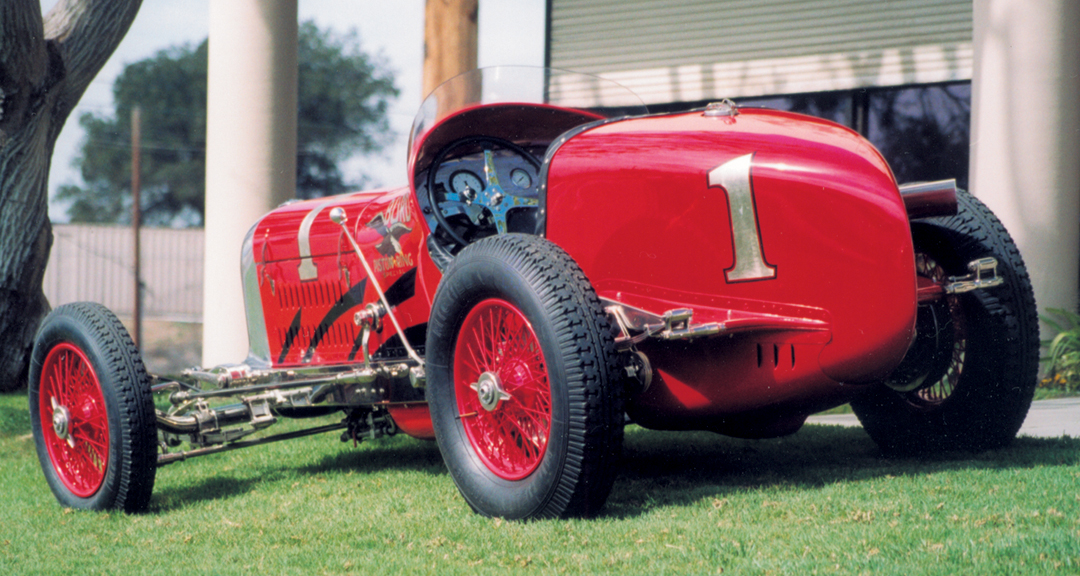

Miller “Burd Piston Ring Special”

On December 9, 1875 an event occurred in Menomonie, Wisconsin, that would directly shape and affect the face of American motorsport for the next 70 years – Harry Arminius Miller was born. Despite having no more than an elementary school education, Miller went on to design and build not only some of the most innovative and successful racing machines of the prewar era, but also a family of racing engines that would virtually dominate the Indianapolis 500 from 1920 to 1978!

By 1895, Miller had moved from Wisconsin to Los Angeles, California and began working in a bicycle factory. By 1905, he was working for Olds as a mechanic, with part of his duties being to help prepare the Olds racecars for the famed Vanderbilt Cup races of that period. However, by 1908, Miller’s creative juices, combined with a longing for independence, had influenced him into opening his own machine shop back in Los Angeles. Miller Machine began its life by manufacturing racing carburetors and by 1915 was offering a range of speed equipment, which also included alloy pistons, mechanical fuel pumps and custom foundry work for the racing trade. Interestingly, Miller’s shop foreman was a machinist/engineer by the name of Fred Offenhauser, who also featured prominently in Indy history.

The Beginning

Late in 1914, racecar owner “Wild Bob” Burman came to Miller with a unique engineering problem that would ultimately become the catalyst for the Miller racing “dynasty.” Burman had bought a Peugeot L56 to race in the Indianapolis 500-mile race. This Peugeot was revolutionary for its time in that its 4-cylinder engine featured twin, overhead camshafts driving 4-valves per cylinder inside a pent-roof (or quasi-hemispherical) combustion chamber. While we take these design features for granted today, it’s astounding to realize that so much of the fundamentals of modern racing engine design can trace its roots to an engine designed near the turn of the century.

Burman asked Miller, who had become a specialist in custom foundry work, to essentially reverse engineer the Peugeot powerplant and build for him a brand new motor. This “new” motor would be Miller’s first complete engine and would become the blueprint for competitive engines at the Brickyard for a stunning amount of time.

Over the next 10 years, Miller engines won numerous board track and oval race events around the country. With such success, it was inevitable that Miller began building complete cars. Miller’s first purpose-built racecar was the fabled “Golden Submarine,” built for the flamboyant Barney Oldfield in 1917. Soon to follow was the first Miller racecar to carry the now-famous Miller straight-8 motor. This car, built for Ira Vail and known as the Leach Special, boasted a 183-cu. in. engine and finished a respectable seventh in the 1921 Indianapolis 500. Over the course of the next decade, Millers were nearly the only cars to win the Indy 500, a record, which has yet to be broken by any other single marque.

Unfortunately, while Miller was a brilliant and entirely self-taught engineer, a great businessman he was not. Miller’s pet engineering projects, such as the development of a V16 engine and four-wheel drive racecars, were driving the company deeper and deeper into debt. Finally, on July 8, 1933, Miller’s creditors filed for involuntary bankruptcy, and Harry Miller lost everything – his business, his engine patterns, even his tools were sold off to pay creditors. While Miller may have personally exited the racing scene for good in 1933, his employees and designs would go on to many more years of racing success on the American scene.

Enter Offy

Just before Miller went bankrupt, his colleague Fred Offenhauser came to him with an idea. Offenhauser suggested that they could scale the successful 220-cu. in. motor up to 255-cu. in.; thus making it more competitive on the dirt tracks and possibly at Indy. Offenhauser suggested that this could be done for very little money and thus could be a new profit center for the struggling company. The first version of this 255 engine showed great promise, but was unfortunately too late to save Miller’s failing business. At the time of bankruptcy filing, Miller owed Offenhauser nearly half a year’s back salary, so Offenhauser put in a claim and was able to take some of Miller’s machine tools as partial payment on the debt. With these tools, Offenhauser went around the corner in Los Angeles and opened his own machine shop to carry on the engine work that he had been developing with Miller for so many years. As luck would have it, Offenhauser was able to strike a deal with Dick Loynes, who had purchased the foundry molds for the Miller 255 motor, and began producing and further developing these powerplants under his own name. The rest, as they say, is history. The Offenhauser engine went on to dominate the speedway and midget racing until the late ’70s.

Later in 1934, two more Miller refugees were finding gainful employment plying the skills that they had honed with Harry Miller – these former employees were Emil Diedt and Ernie Weil. After leaving Miller, Diedt and Weil were hired by Indy 500 driver and entrant Lou Moore to build a new “Foreman Axel Special” to replace the one that had tragically claimed the life of Joe Russo at Langhorne in June of that year. Using a number of salvaged Miller pieces from other cars, Diedt and Weil built for Moore a “new” Miller frame and engine to house the Miller/Offenhauser 255 engine saved from Russo’s crash. This new car would enjoy a great deal of success over the coming three years including winning the 1936 AAA Championship at the hands of Mauri Rose.

The Burd is Born

The subject of this month’s profile started life in Los Angeles as the second generation “Foreman Axel Special.” While the car was not technically constructed in the Miller factory, it was entirely of Miller design, Miller components and was built by Miller employees. This is born out by the fact that it was always entered as a Miller/Miller (Miller frame and Miller engine) at Indy and other events and was certified as such by both the AAA and by Indy authority Jack Fox.

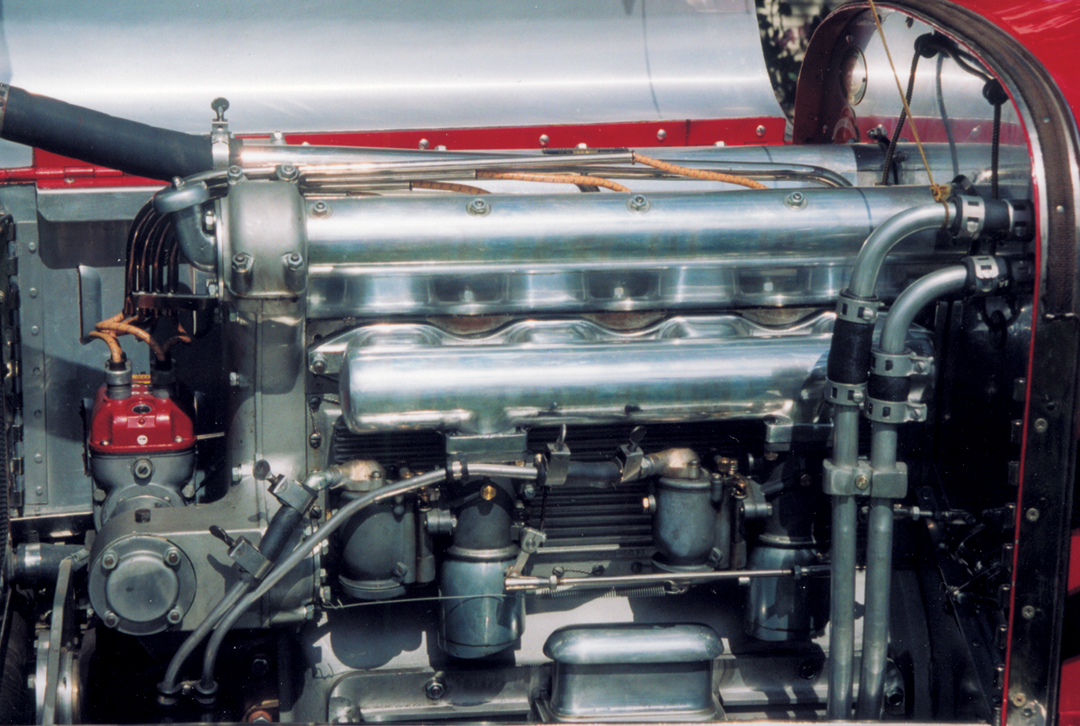

As with all Miller’s of the time, Moore’s car utilized a hand-beaten, steel-channel-type ladder frame with a beam axle suspended by semi-elliptical springs in the front with Gabriel friction dampers. The four-cylinder, 255-cu. in. Offenhauser twin-cam motor fed power through a combination of a Miller-modified, three-speed gearbox and a Miller-built torque tube live axle hanging from semi-elliptical springs in the rear wirth Houdi-Hart friction dampers.

Racing History

The second generation “Foreman Axel Special’s” first race was a dirt track event at Springfield, Missouri, in August 1934, where future Indy 500 winner Kelly Petillo and his riding mechanic Louis Webb qualified third and finished fifth. This race was subsequently followed by a disappointing 15th place finish at Syracuse, New York, in September.

By December 1934, car owner Moore had changed the name of the car to the “Red Lion Special,” and now had fabled Indy champion Wilbur Shaw driving the car with Webb again as codriver. At Mine’s Field, the team qualified second and finished second taking home a handsome $1,500 in prize money.

Photo: Casey Annis

For the 1935 Indy 500, car owner Moore elected to return the car to “Foreman Axel Special” livery and drive the car himself with the help of riding mechanic Lyman Spaulding. After qualifying a lowly 23rd, Moore finished a disappointing 18th after a connecting rod let go late in the race.

Over the course of the coming year, the car was raced by both Moore and Shaw at places like, Altoona, St. Paul, Springfield, Ascot and Oakland with several top 10 finishes. For the 1936 Indianapolis 500, Moore and riding mechanic Louie Webb qualified the now-rechristened “Burd Piston Ring Special” 29th on the grid. Moore ran competitively in the race until he handed the car over to relief driver Cliff Bergere. Unfortunately, Indy 500 rules for that year dictated a fixed amount of fuel which could be used for the entire race distance, resulting in Bergere running out of gas near the end and ultimately finishing in 17th position.

After the 1936 Indy 500 debacle, Moore hired ace driver Mauri Rose to pilot the “Burd Piston Ring Special.” Rose drove the Miller to a sixth-place finish at Goshen, (this race was significant in that it was the first dirt track race run under the AAA’s new rule that forbid the use of riding mechanics in one-mile dirt track events). Next, Rose took a convincing win at Syracuse, which was followed the next month by the much anticipated return of the Vanderbilt Cup races, which had originally risen to international notoriety from 1904-1910.

On October 10, 1936, the famed Vanderbilt Cup Race was revived on Long Island’s Roosevelt Speedway. The prestige and large cash prize drew some of the best Grand Prix teams from Europe, including the Alfa Romeos of Scuderia Ferrari driven by Nuvolari, Brivio and Farina, as well as the Bugatti of Wimille and the ERA-A of Fairfield. The Europeans competed against a host of American oval track racers, including Rex Mays and Mauri Rose driving the “Burd Piston Ring Special.” Ultimately, Nuvolari won the twisty road race run on loose dirt in his Alfa Romeo, with Rose finishing as the highest placed American car in sixth place. This finish, combined with other points scored throughout the year, garnered Rose the 1936 AAA Driving Championship.

Subsequently, Rose would go on to race the Miller one more time at Indy in 1937 utilizing the larger 270-cu. in. Offenhauser motor, but a ruptured oil line would leave him finishing only 18th. In future years, Rose went on to win the Indy 500 driving one of Moore’s later-model “Burd Piston Ring Specials” in 1941 and again for Moore in 1947.

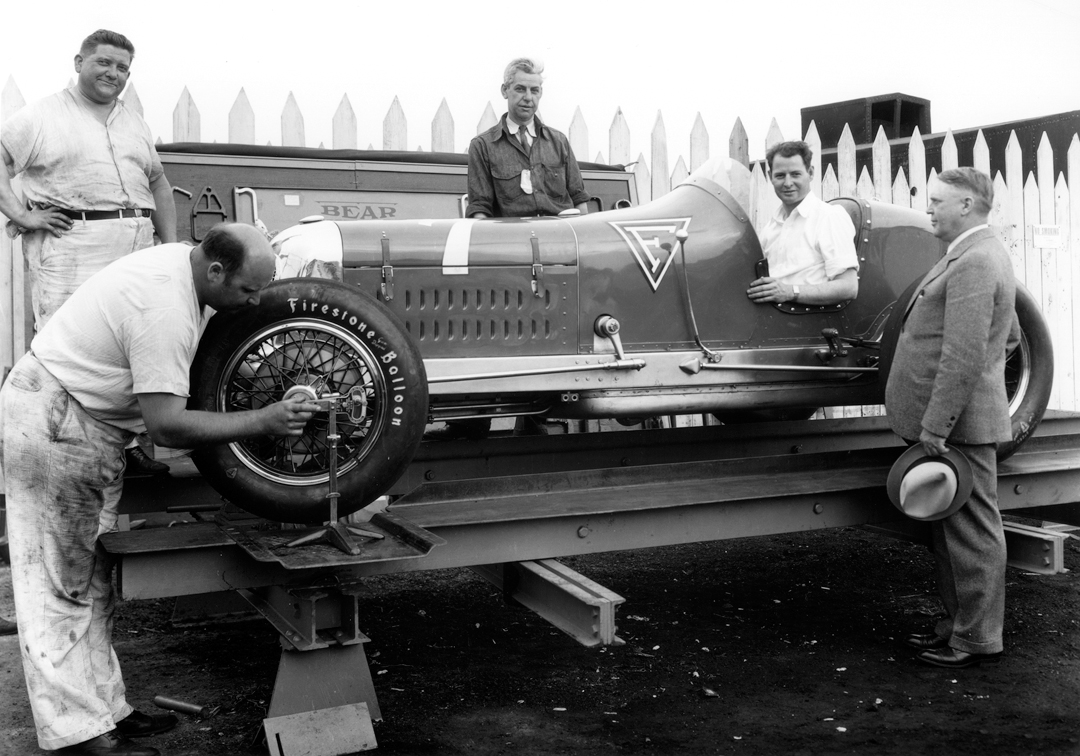

Photo: Malloy Collection

Moore’s Miller was sold at the end of the 1937 season and did not race competitively again. However, the “Burd Piston Ring Special” may have indirectly laid the groundwork for several Indy 500 victories in later years. As luck would have it, the car was sold to a Don Thompson of Coffeyville, Kansas, who licensed the car and allowed his son and his son’s friend to drive it on the street in 1953. The pair were reported to have terrorized the streets of Coffeyville in the Miller for quite some time. The name of that young friend who cut his teeth in the Miller… future 3-time Indy 500 winner Johnny Rutherford.

Driving an Indy Legend

As I approach the beautifully restored “Burd Piston Ring Special” for my chance behind the wheel, I can’t help but think of the brickyard legends that have occupied the same seat – Wilbur Shaw, Mauri Rose, Kelly Petillo and so many others. As I climb behind the wheel, I come to realize something about Shaw and Rose that I never realized before – they were really short! As I try to wedge my legs under the large, truck-like steering wheel, I experience a moment of panic – I can’t get my left foot anywhere near the clutch pedal! The driving position is fully erect with the driver’s legs splayed to either side of the large steering wheel. This, combined with the closely spaced, tiny pedals and the fact that my left leg is bent at nearly a 90-degree angle and crammed against the aluminum bodywork, means that either my left foot covers both the clutch and the brake at the same time or is useless. After getting so excited and psyched up to drive this piece of speedway history, I was beginning to wonder whether I’d get the chance. However, determined not to be denied this rare opportunity, I took my shoes off and found that I could just clear the pedals in my stocking feet.

With this potential calamity solved, the car’s owner Tom Malloy and his mechanic Mark walk me through the starting procedure. Interestingly, the first order of business is pumping up the fuel pressure by hand. During the car’s day, it was the job of the riding mechanic to maintain fuel pressure by pumping a hand pump mounted on the passenger-side cowl. I’m told that I need to maintain 6-9 pounds of pressure throughout my run. After pumping up the fuel pressure, the main electric switch is turned on and the engine is cranked over with the on-board starter until signs of oil pressure appear. As soon as I see oil pressure, I’m told to flip the magneto on and – BOOM – the four-cylinder Offy roars to life – and roar it does. The four-cylinder Offenhauser motor has a very distinctive engine note, which is simultaneously low and yet sharp.

Photo: Malloy Collection

After a few minutes to warm up the motor, I pull my sock-clad foot back to engage the clutch and slip the three-speed gearbox into first, give the motor about 1500 rpm and gently slip the clutch off the line. First gear in this is a real stump-puller. So by the time I’m fully away it’s already time to shift into second. The gearbox is very heavy, but positive, as I clunk into second and feed on more power. The incredible versatility of the Offy is immediately evident as the motor pulls virtually from idle right up to redline. The power and shear grunt were amazing considering the age and the era that this car was designed and raced in. As I approach the first turn, racing along in second gear, I become accutely aware of how high and exposed the drivers sat in these cars. This, combined with absurdly skinny tires, no seat belts and a bootful of torque and horsepower, reaffirmed in my mind what a brave and dedicated breed drivers were in the early days.

As I approach the turn, I press on the tiny brake pedal and for a moment wonder if I’ve caught the clutch by accident – the car didn’t seem to be slowing down. The drum brakes on these cars were never outstanding and the fact that these were stone cold didn’t make them any better. However, as I feed the power on through the apex, I am treated to the sweet roar of that motor with just a hint of rear-wheel drift.

Accelerating down the following straight, I catch third and briefly get a true sense of the car’s speed potential. Despite having only three speeds, these lightweight cars were good for 120 mph in their day – as I mentioned previously, scary-fast considering the high center of gravity and driver’s relative exposure.

However, with each successive turn and straight, I become more accustomed to the ways of the Miller: smooth throttle application, strong acceleration and easily balanced drifts. I even get used to the idea that I have to remember to pump up the fuel pressure periodically. After a few more laps, I bring the car back in and shut the mighty Offenhauser down with a final blip of the throttle. As I step out of the car in my oily socks and “puddin’ bowl” helmet, I immediately become overtaken by an urge I haven’t had since I was a kid, “Anyone got a bottle of milk?”

Buying and Owning a Miller

As with most significant racecars, the prices of Millers are very much influenced by their racing histories. A Miller with real Indy history can range anywhere from $300,000 to $500,000, with particularly significant “winning” cars going for much more.

While the cars are fairly straightforward to maintain, one area that can pose a potential problem is replacement parts. Since most of the parts for both the frame and the engine were manufactured by Miller, these have become very rare. A small community of owners and restorers have collected and preserved a number of these pieces, but they are not normally offered for sale on the open market. In many cases, the only way to obtain these is by trading, which can be very difficult if you are either not connected with the right people or don’t have anything of interest to trade! However, like owning an early prewar Bugatti or Alfa Romeo, a genuine Miller Indy car can be a fast and very rewarding time machine back into history.

Specifications

Chassis: Ladder type of hand formed channel steel.

Bodywork: Hand formed aluminum.

Weight: 1875 lbs.

Wheelbase: 100”

Front track: 57.25”

Rear track: 56.34”

Suspension: Front: Beam axle with semi-elliptical springs and Gabriel friction dampers. Rear: Miller live axle with semi-elliptical springs and Houdi-Hart friction dampers.

Engine: Offenhauser in-line, 4-cylinder, double overhead cam.

Bore and stroke: 4.3125” x 4.625”

Displacement: 269.6 cu in.

Ingnition: Bosch magneto.

Induction: Twin Miller 1 5/8” carburettors.

Horsepower: 250 hp @ 5000 rpm

Gearbox: Miller-modified Ford 3-speed.

Brakes: Hydraulic drums front and rear.

Tires: Front: Firestone 18 x 550. Rear: Firestone 18 x 700

Fuel capacity: 15.3 gallons.

Resources

Miller Dynasty, Second Edition

Mark L. Dees

Hippodrome Publishing, 1994

ISBN: 0-9638084-0-0

Classic Racing Cars

Cyril Posthumus

Hamlyn, 1977

ISBN: 0-600319091

Offenhauser

Gordon Eliot White

MBI Publishing