1967 Lola T92

This story is a little like finding a Bonneville record car at the North or South Pole…you don’t really expect it. We took a famous Indy veteran far from home to the Italian hill country to give it a run in a totally new territory. It caused as much excitement there as it had 42 years ago, and like Indy ’67, we had some adventures along the way. We also learned a lot about the “secret identity” of many of the great cars that had experienced the “Brickyard.”

Lola goes to Indy

Cast your mind back to 1961 and the qualifying days for the great American racing event, the Indianapolis 500. The World Champion Jack Brabham had brought a diminutive Cooper to the Brickyard to see what a rear-engine Grand Prix–type car could do against the front-engine, mostly Offenhauser-powered roadsters that had ruled for years. While Brabham didn’t win…he finished 9th…he not only brought howls of protest, but he got a lot of people thinking about how racing might begin to change.

The following year brought the presence of Colin Chapman of Lotus, as Dan Gurney tried unsuccesfully to qualify a turbine-powered car, the John Zink Trackburner Special, then managed to make the race in Mickey Thompson’s rear-engine machine, but a front-engine roadster won, and did so again in 1963 despite the presence of more European-inspired devices. A.J. Foyt did it again in 1964, though by then there were many Grand Prix drivers present and a lot more cars with the engine in the back. Everything changed in 1965, when Jim Clark brought his Lotus home first. Clark was powered by the Ford 4-cam engine which had only made its debut the previous year. Though a revered power plant, it wasn’t that special, being basically a Fairlane block with heads very much akin to Offenhauser’s…but it worked.

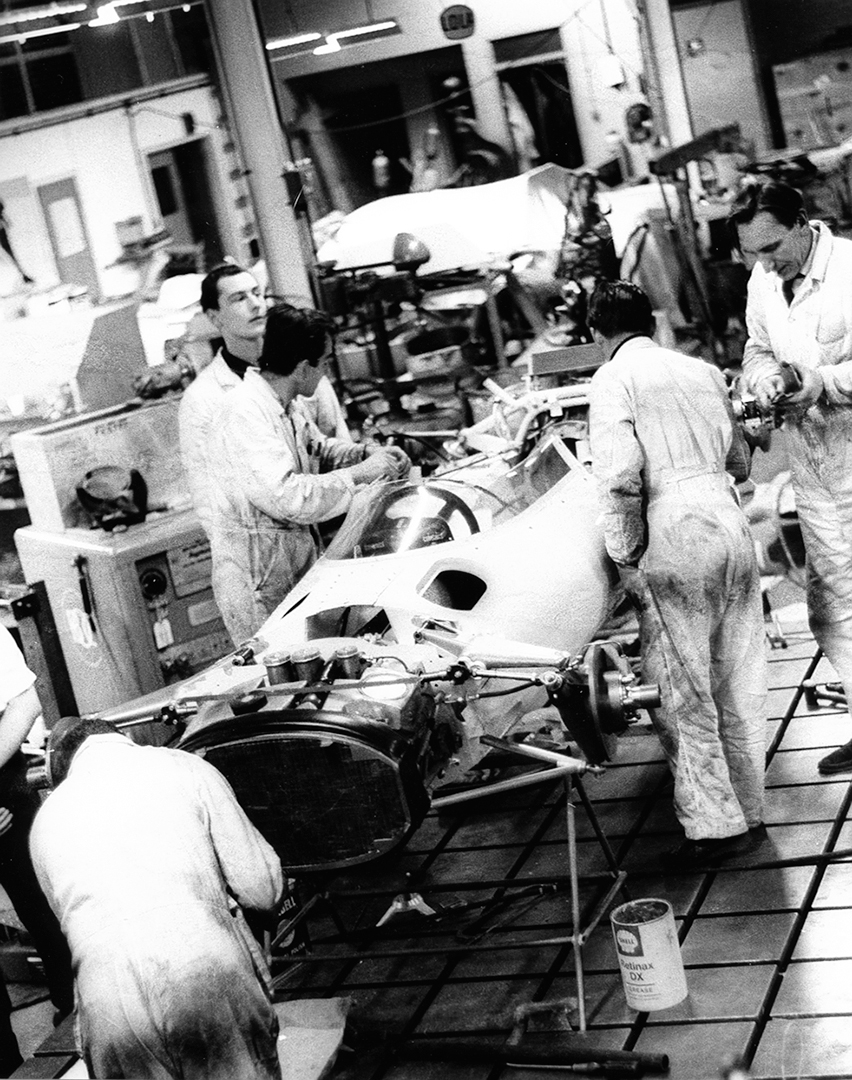

Back in England, Lola boss Eric Broadley, always a competitor to Lotus and Colin Chapman, had taken notice of just how much money was to be earned at Indy. Lola had grown, literally, from nothing, and an injection of American money would do much to enhance the company’s future. So Eric had set about designing a car for the Indy 500, and he joined the party in 1965. No one, especially Eric Broadley, would have even been able to speculate then that, by 2009, some 426 manufacturers—from Adams and Alco to Watson and Wildcat—would produce “Champ cars.” It was unimaginable in 1965 that Lola would amass 528 race starts, a total of 4,715 driver starts, win 193 Champ car races, and get 185 pole positions, the most successful record of any car builder in every category. (Watson was 2nd in race starts and Dallara 2nd in wins.)

Broadley was inclined to view Indianapolis, at first, as not a complex challenge. After all, the handling only had to cope with a succession of left-hand bends; there was little braking, and gear-changing only when leaving the pits. However, he also suspected the reality would be more demanding as it always is. What he did recognize was that suspension setup was of ultimate importance, and that a car had to be able to enter every corner in a stable condition. Eric considered himself to be up to the challenge, as suspension geometry was just about his favorite subject. Mention “suspension geometry” even today to any veteran Lola mechanic and he will shudder, as Eric was known to adjust and adjust and adjust!

Three of the new Lola T80 models were sent to the United States, for A.J. Foyt, Parnelli Jones, and Bud Tinglestad. The cars were rather late in being completed and did not arrive at Indy early enough for Jones and Foyt to feel confident enough to race them. However, Tinglestad qualified his car, and ran as high as 5th when a wheel casting failed and he was forced to retire. Al Unser took over the car that Foyt was using as his back-up and came home in 9th. Ironically, one of the things that troubled the drivers was the result of getting the suspension geometry wrong, with the cars giving a sharp upward heave on the exit of corners!

The T90 and the T92…one and the same?

For 1966, Broadley designed a new car for Indy, generally along the lines of the T80 but with many refinements, and the 1967 T92 would be a further advance on the same design. This is evolution, though it also brought with it substantial headaches in identifying the cars in later years!

The T90 chassis was a 16-gauge aluminum monocoque, a well-built affair with Firestone fuel cells housed in each side of the monocoque hull, running virtually from the front to rear of the car. The front of the T90 was improved and strengthened to manage the large fuel fillers, and a great deal of work had gone into designing the baffles within the fuel tanks to prevent fuel surge. Both the front and rear suspension was offset to the right to cope with left-hand-only turns, though the offset was reduced from 1965. Broadley was known to have said that he had doubts about the need for offset suspension provided the general balance of the car was correct. The front suspension was conventional with faired-in upper links operating combined coil spring and damper units. Broadley also had his own brand of clever anti-roll linkage to provide a substantial anti-roll bar. The rear suspension was also a challenge, as the large fuel tankage meant there was very little room for a lower radius arm…so it was omitted!

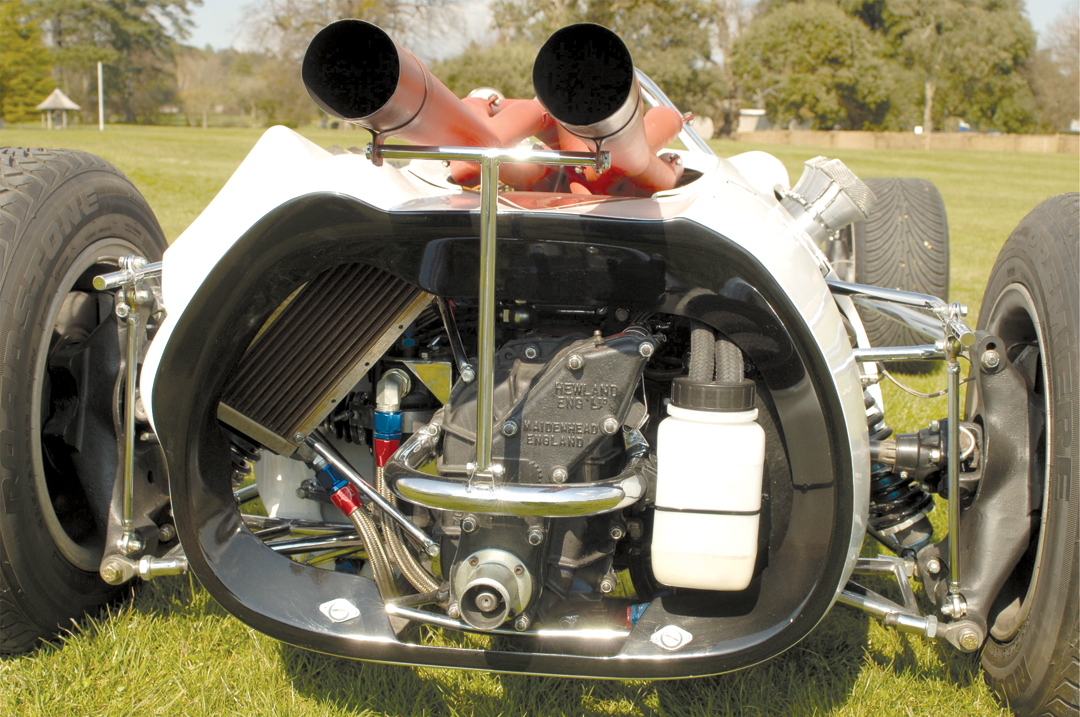

Broadley designed the chassis to accept either the new 4-cam Ford of 4.2 liters, or the 2.9-supercharged Offy unit. Either engine could be mated to the two-speed Hewland gearbox, which is surrounded at the rear by a protective metal “cage” attached to the rear monocoque. The car was also capable of taking a 4-speed gearbox, which it used rarely, though I was fortunate enough to be able to sample both. Incidentally, the 4-cam Ford was in effect no stranger to Eric Broadley. He had used the Fairlane engine in his Mk 6 sports cars, the precursor to the Ford GT40. The 4-cam consisted of new twin-cam heads, fitted to each bank of the alloy Fairlane block. The T90 was entered at the Phoenix season opener in March and Rodger Ward brought it home a convincing 2nd with the blown Offy engine behind him. In April, he gave Lola its first of many Champ car wins when the same car won at Trenton, only a week before the action started at Indy.

The cars had been ordered by Texas millionaire John Mecom Jr., and he had signed Jackie Stewart to drive the car known as the Bowes Seal Fast Special. Earlier thinking had included the notion that John Surtees would be in an Indy Lola but his serious accident in late 1965 meant he would have to be replaced in the team. Walt Hansgen was going to be the driver, but alas he, too, became a victim, killed at Le Mans testing in 1966. Thus, Graham Hill came to drive one of the two Ford-engine cars, while Rodger Ward would again be in his T90-Offy machine.

Mecom had the well-known George Bignotti as chief mechanic, and the team was a very professional outfit, though Mecom would later say he never quite got to grips with Indy. Stewart immediately got to grips with the T90 and Indy in the late March tire tests, turning laps at 158 mph, and also managing the odd spin for good measure.

The 1966 Indy 500 is remembered for many things…the first-lap crash, Hill’s great achievement, the strength of the Lolas, and the arguments at the end. Stewart had settled in and qualified 11th at over 159 mph, Ward was 13th a fraction slower, and Hill 15th just behind.

Two cars collided heading for Turn One on the first lap, putting 11 cars out immediately, including Foyt and Gurney, and the race was stopped for an hour to clean up. It was restarted under the yellow flag, which stayed out until lap 17. Mario Andretti took the lead but retired quickly as his engine had been damaged. Jim Clark then put the Lotus in front, but handling problems led to a couple of famous spins, so Lloyd Ruby in the Eagle now had a fight on his hands with Stewart. Ruby was in front when he was black-flagged for dropping oil, and Stewart looked to have the race in the bag, ahead of Hill in the Red Ball Express and Clark. With only 10 laps to go, Stewart saw his gauge register no oil pressure, so he pulled over and pushed the car up pit lane to much applause. Graham found himself in front and dutifully took the flag. Clark’s sponsor, STP’s Andy Granatelli, filed a protest, saying the timers had it wrong and that Clark had won. Jimmy walked up to the Victory Circle and asked Graham what was going on. Graham said, “I drank the milk, so I must have won.” Granatelli later apologized to Mecom, saying he knew he had to get some publicity for all the money he spent, so that’s what he did. It worked.

Lola reveled in the success. Later in the season, Mecom sent Hill and Stewart and their Lolas to Japan to take part in the non-championship race at Fuji. Stewart drove quickly, like an experienced Indy car man, and won the race. Hill had been close to him, but this time his engine went, and he retired, still classified 7th. Stewart was getting an appetite for Indy cars, as well as starting a long relationship with Lola that continues to endure.

The T92–“Murky” waters.

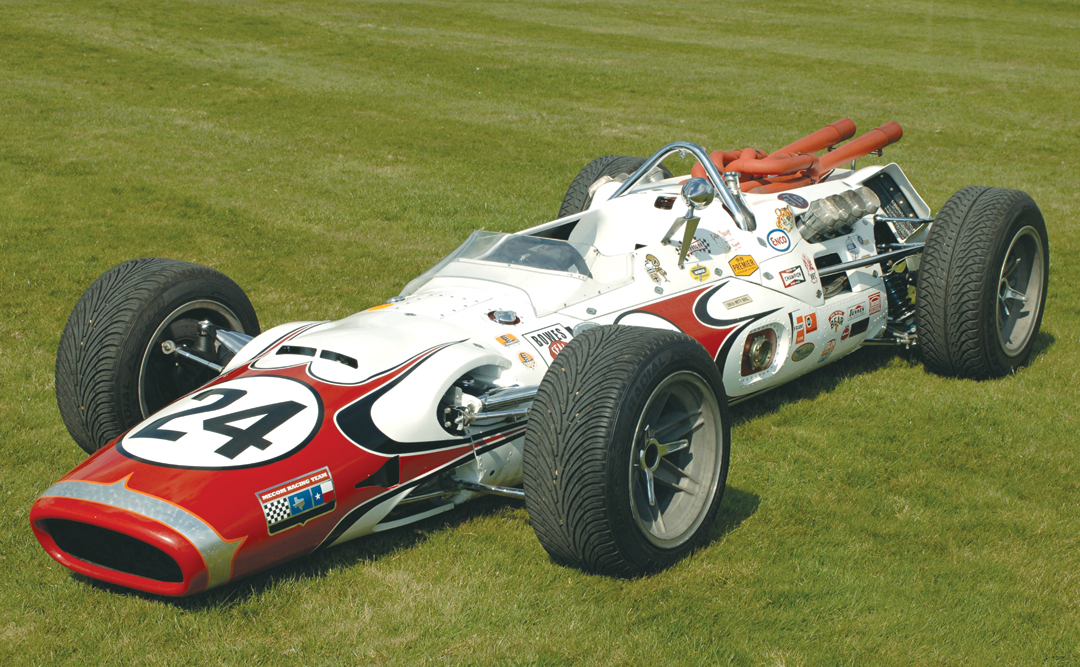

Indy cars, or Champ cars, are part of a very American culture, even more so part of an Indy 500 culture. The cars have always been known by their sponsors’ names…there is a potential book here on weird car names…in ’65 Jim Hurtubise nearly killed himself trying to qualify the Tombstone Life Special! Cars have thus been remembered, not by who manufactured them, but by their name, sometimes by number, and almost never by chassis number. This simple fact makes tracing Indy car history a very intriguing activity, as I found attempting to discover the history of “our car.” Jackie Stewart drove car #43 in 1966 and Hill drove #24. In 1967, Stewart drove both 43 and 24…maybe, while Hill had departed to Lotus. Some key people legitimately believed some stories, and other people were accused of making fakes. The reality is very interesting.

First, let’s review 1967. The T92 was very similar to the T90, with a different cockpit surround and engine cover, and some refinements, but overall it was close to the T90. When it was entered, again by John Mecom, for the 500, it was entered as a T92. USAC officials refused to accept it as a T92, stating that it was not different enough, so it was called the T90 MkII. The plate on the dash shows how Eric Broadley got back at them, as the plate says “T90 MkII – SL T92/3.” That would indicate that this is chassis 3, though deeper investigation shows it is most likely chassis 5. Thanks to Walter Goodwin who continues to restore Indy cars in Indianapolis, we know this is the 1967 Stewart racecar.

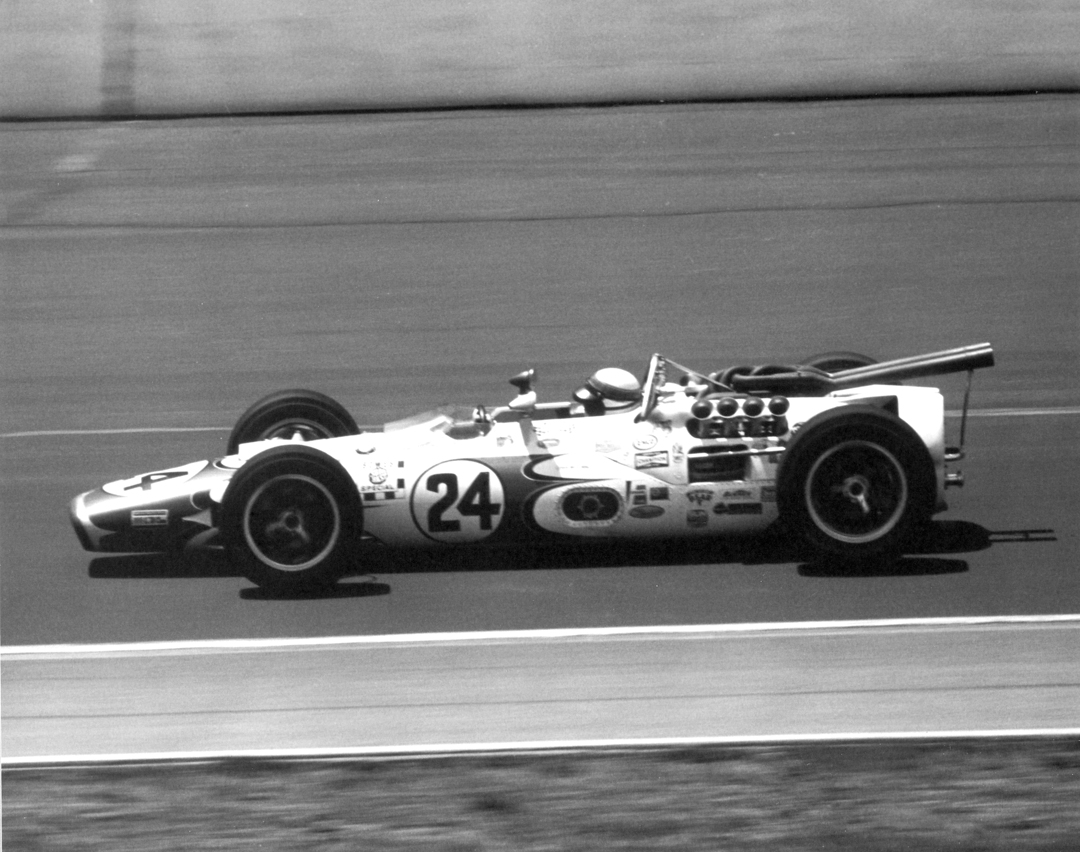

The unraveling of the history was not assisted by what happened in 1967 qualifying. Reports over the years have said that Mecom brought three “new” cars to Indy for ’67. Some have said they were “new” in that they were T92s, but others argue they were updated T90s, or possibly a combination of both. The cars were entered for Stewart and Al Unser, Unser being backed by the Retzloff Chemical Company.

Stewart was down to drive the #43 car, but the Grand Prix drivers weren’t having it so easy this year. He set a slowish time and was “bumped” by faster cars, so he faced taking a second car into qualifying the second week. This would logically be the #24 spare, and pictures show the car in one official photo as not having been fully “stickered” up. One theory is that the spare was used to qualify, but that the original car was worked on, possibly made to look like the qualifier, and thus Stewart raced a car that had not qualified. Now these were not unusual tricks at Indy, and others did far worse things…allegedly!

In the race, of course, Parnelli Jones looked like he would disappear in the turbine car. Then, for the first time, rain caused the race to be stopped and restarted the next day. Stewart worked his way through the field, and was up to 3rd with 25 laps to go. Then the engine faltered once again and the Scot was out. Granatelli was on his way to greet his winning driver, Jones, when the gears in the turbine car failed with three laps left. A.J. Foyt won and Al Unser brought the other Lola T92 in 2nd.

In late November, John Surtees was back in fine form and took over Stewart’s seat in “our car,” still in Bowes Seal Fast livery with #24, and ran it at the Riverside road circuit. The occasion was the Rex Mays 300, and Surtees did well in his only USAC race to qualify 4th. The 4-speed gearbox had been put in the Lola T92. He had felt the engine was lacking power but was running well until lap 30 when he came in with a misfire. He did a few more laps and then called it a day. Two World Champions had driven the car.

Of course, by this time in 1967, Surtees had gotten Honda to let Lola build them a more competitive chassis than the heavy Honda RA273. Lola took a T92 chassis to which it grafted the Honda V-12 engine and, presto, the Lola T130 or the Hondola…or the Honda RA300! Surtees took it to Monza and won first time out.

Driving an Indy Car…uphill!

I have read hundreds of pages of information about the Lola T90/92s and where they went after Indy 1966/67. I have seen the legal depositions, and letters from lawyers spanning 40 years. It is fascinating. Very little of it is underhanded. John Mecom Jr. sold the Graham Hill car after Indy in 1966 and, when he was told it had been later crashed and written off, he believed it, and thus a very significant person had said there was no Graham Hill winning car from 1966. Mecom sold the car to Interstate Racing and one Bif Caruso. The check bounced, and Mecom never got paid. When Interstate had no funds, Lindsay Hopkins backed the car for Chuck Hulse who crashed in the ’67 Indy race. Caruso, it is said, took the bent chassis home to California. When he later saw the Mecom crew chief, he told him the car had been crushed, as he had never paid for it, and it was now a flower pot somewhere. However, he sold the car, and eventually Phil Henny had it restored and some time later it got to Pat Ryan complete with 4-cam engine. Walter Goodwin was also strong on the fact that Stewart’s ’67 car was a new chassis and not a 1966 chassis upgraded. And also, as we discovered, the chassis plates were moved around!

It would thus be easy to get totally lost in the mysteries. However, the most telling legal documents are those that confirm that Martin Birrane, now the owner of Lola, bought the Stewart car from John Mecom, as Mecom went to the trouble of finding his old cars and buying them back.

As the 50th anniversary of Lola Cars approached back in 2007, the cars were readied for a number of events in preparation for celebrations in 2008. Early in 2008, I had my first moving encounter with the Stewart car, as it appeared at the Goodwood Festival of Speed press day. I had a chance to sit in the pristine T92 and talked through the details and history with Barrie Williams who was demonstrating it…and trying to work out what to do with a 2-speed box that had been in the car when it was restored. The Lolas were well received at the Festival, but there were others who wanted to see them.

Claudio Casale, the prime mover behind the great cars that journey to the Silver Flag Hillclimb in Italy, asked if I could make inquiries about whether Lola would attend a 50th-anniversary celebration at the Silver Flag. Lola Heritage’s Glyn Jones, with Martin Birrane’s blessing, and I thus headed off to Italy in July, with my wife Nancy making her debut as Indy car crew person! The adventures had started.

Now, some readers are familiar with the Silver Flag, a 9-kilometer hillclimb from Castell’Arquato to Lugagnano to Vernasca. Some historic events are races interspersed with meals. This one is meals interspersed with races! Not far from Piacenza, the Silver Flag brings out the best of Italian historics, and increasingly cars from around Europe. The Italians have very rarely seen an Indy car, and they had never seen one that would go winding up one of their mountains. We were never without company and help, including the delivery of methanol, as that is what this Ford 4-cam runs on…plenty of it. It appeared!

Claudio had organized a Lola “enclave,” and a dozen Lolas had their own space in the paddock. On Saturday, as I sat in the car, I asked Glyn about the gearbox, as there had been discussions about putting the 4-speed box in. He suggested that I would find out when we started it! As it happened, this was not an altogether easy process. The car hadn’t run in some weeks and all the fuel had come out, as happens regularly with methanol cars to preserve them. It didn’t want to start at first, so we had an offer from the local polizia/carabinieri to assist. Glyn got in and they slowly towed him down the paddock. Too slow, I thought. Then I realized what they were up to. They got him out onto the main road, stopped everyone else, and towed him until that fabulous engine burst into life. Up the road he went to warm it up as the prestart crowd gathered. The police brought him back and they stayed with us all weekend, hoping to do it again.

It was time for me to climb aboard for an official run, a truly daunting experience. I settled my backside onto the Stewart tartan…the seat cover was there courtesy of Jeanette Jones. Jackie said he wouldn’t drive at Goodwood without it, and Mr. Jones got Ms. Jones to make a template and construct the final effort. The cockpit is wide and roomy, the gauges are pretty minimal…the rev counter reads to 10,000, and there are oil and water gauges, and that’s all. But the serious part is knowing that this car is methanol fueled and that, when methanol is alight, you cannot see it. As methanol has to be sprayed into the intakes via the old plastic squeezy bottle, everyone gets a little nervous, especially the driver. Glyn hoisted the heavy Gerhardt mechanical starter into place, shouted instructions, and within seconds, the Ford screamed and I was out to the start line. I had learned by now that the 4-speed box was in place, which made the process a lot easier.

In spite of this car’s pedigree and specialist nature, it was amazingly manageable…no stalls, a reasonable clutch, lots of feel…but noise…lots of it. The great Italian woman Grand Prix driver Maria-Teresa de Filippis was the official starter, and she made a show of bringing the Italian national flag down on my head! The revs rose and slightly too enthusiastically the T92 smoked off the line, clearing the plugs and getting the tail at a bit of an angle, quickly straightening up, and then taking off again.

The first 4 kilometers of this “hill” are virtually flat, with a series of five chicanes set up with plastic cones by the marshals to keep speeds in hand. As the Indy car came out of a fast bend before the first chicane, the marshal saw which car it was, and kicked the cones aside urging me to “go…avanti.” Thus, on public roads, I pressed on, ignored the now-moved chicanes, and touched perhaps 175! Into Lugagnano, it was on the very steady brakes, down to second gear, trying not to watch hundreds of people jumping up and down just a few feet away. The road wanders straight downhill until the real all 2nd- and 3rd-gear corners start. I used first once, and the rear came away and I just caught it, resolving to use second and third only. In no time, the T92 was at the top, drawing another huge crowd. The car now runs on an unusual Roadstone radial road tire, as it is near impossible to find competition tires in this size. However, they worked very well indeed, and as Goodwood had proved, they worked in the wet as well.

The weekend provided a chance for me to learn the Gerhardt starter…what a job! As I went for my second run, I looked over and saw that Nancy, who had been using the squeezy, was madly shaking her hand…she had set herself alight…now that’s a real woman! The second run brought us the reward of “quickest car,” Glyn got to drive a T294 sports racer and won his class. It had been a true Lola celebration.

Specifications

Chassis: All aluminium 16 gauge monocoque, with sheet steel diaphragms front and rear of the tub with additional stiffening braces; tubular steel sub-frames attached to front and rear for oil tank, radiator, etc.

Suspension: Front: Inboard with fabricated rocker arms at the top operating coil and damper units and wide-base lower suspension; front anti-roll bar linked to inner ends of rocker arms; Rear: Conventional except top upright has a single adjustable top link attached to top chassis subframe; adjustable single lateral link from lower front upright to subframe; Suspension offset three inches in 1966, dropped in 1967.

Engine: Ford 4-cam eight-cylinder, Fairlane alloy block with four-valve heads

Power output: 540 bhp

Capacity: 4.2 liters/255 c.i.

Gearbox: Hewland 2-speed/Hewland 4-speed

Brakes: 4 wheel discs

Tires: Currently on Roadstone radial road tires – Front: 225/50R15 – 91V; Rear: 225/55R16 – 95V Firestones used in period

Resources

Many, many thanks to Martin Birrane, Glyn Jones, Gerald Swan, and all those who helped with the history, to our police friends who helped with starting, and to Claudio.

Starkey, J. Lola

– The Illustrated History 1957 to 1977

Veloce Publishing 1998

www.Lolaheritage.com

Autosport, Motor Sport, The Motor, Autocar

– 1966–1967