Imagine what it was like for Eric Broadley to have come up with the T70 coupe after the heady days of his venture with Ford. The Ford program had earned the company some money and provided the impetus to develop the T70 in both coupe and open form. The T70 was driven in the Can-Am by men such as Dan Gurney, Mark Donohue, David Hobbs, and John Surtees, with Surtees taking the 1966 Championship by posting three wins from six races. The gorgeous T70 was an immense boost for Lola fortunes, and the car enjoyed success in both Can-Am and endurance racing for several years.

When the rules, styles, and technology began to change, however, so did the cars, and Lola’s next generation was to be spearheaded by the T160. It faced living up to a reputation that was almost too good to be true and, not surprisingly, it had trouble doing so.

1968—Changing Times

The FIA brought a new set of regulations into effect for 1968, creating Group 4 for cars of which at least 50 examples had been built, as well as a new Group 6, for 3-liter prototypes. Having built nearly 50 T70s, Lola believed it could homologate the car and dominate Group 4, but the FIA then decided to lower the homologation minimum to 25 cars, and along came Porsche’s 917 and Ferrari’s 512 to deal Lola’s “sure thing” a big setback. Nevertheless, the T70 continued to do well in endurance races, at least until the 917s got into their stride.

Broadley decided that to win in the Can-Am a new car was needed to succeed the T70, and that new machine became the T160, but Broadley’s innate cleverness could cut both ways. The T160 had a special purpose, to allow Lola to fit big 7-liter American engines into its cars; but along with being the new Can-Am contender, it would also be part of the development of the next phase of the T70—the MKIIIB. While Eric’s cleverness included making the T160 and MKIIIB parts as interchangeable as possible, he didn’t allow for adequate development of the T160 as a Can-Am car. Well, that’s the simple view. Reality was a little more complicated.

The T70 MKIII, by 1968, seemed to have reached the end of its development for the American market. For Can-Am racing, more power was essential, and the 7-liter Chevy engine just wouldn’t fit into the back of the standard T70. To handle the extra power, a stiffer tub and more adaptable suspension were needed. The T160’s monocoque was consequently much stiffer than the T70, and displayed impressive torsional rigidity even though it was actually lighter. Suspension design was very much traditional Lola, but stronger. John Surtees tested the new car in May 1968. Dan Gurney and James Garner were among the first to order cars for the Can-Am series, and Surtees bought a car for himself, “re-branding” it a TS-Chevrolet and incorporating a number of his own modifications. Cars were sold to the U.S. market by Carl Haas, although only two of the new cars arrived in time for the start of the new Can-Am season.

Two T160s showed up for the season opener at Elkhart Lake with Chuck Parsons in the Haas-entered, Simoniz-sponsored machine, and Brett Lunger in a second example. Parsons qualified 6th fastest, but blew the engine in the race, while Lunger finished 12th. At Bridgehampton, Parsons and Skip Scott (in a second Haas entry) both languished midfield and retired with engine problems, while Sam Posey, reputedly one of the few who actually liked the T160—finished 9th, then scored a fine 4th at Edmonton, while Scott took 8th. Parsons was again 6th on the grid at Laguna, but lost a wheel while running well; and Swede Savage crashed the Ford-engined, AAR-entered T160. Scott finished 7th, with Posey 9th and Brian O’Neil 15th. Subsequently, Parsons finished 11th at Riverside, and took a fine 4th at Las Vegas, just ahead of Posey. Surtees ran his TS160 at three races, retiring every time out, his main problem apparently was the Weslake heads on his engines.

Overall, the performance of the T160s was disappointing, and not particularly helpful for Lola’s aim to sell cars to private teams and owners. While the new chassis could accommodate the big-block Chevy engine, it was a full-length monocoque, not a design where the engine served as a stress-bearing member. Even without steel bulkheads, it turned out overweight, a problem not readily cured even with judicious use of magnesium. The lack of victory in 1968 didn’t stop Broadley from trying to improve the basic design, however, and subsequent T162, T163, and T165 versions were produced.

Only two T162s were built, both based on the T160, though these chassis were identical to that of the new MKIIIB. The T162 and the slightly more modified T163 featured better, more aerodynamic bodywork and improved suspension. One of the issues that makes it difficult to trace the history of these cars is that they all had T160 chassis numbers. The car you see here is T160/9, which was updated with T163 bodywork for the 1969 season, while the two T162s were T160/13 and 14. Some of the cars in the 1969 and 1970 seasons were built as the later versions, and some were earlier cars with the modifications. It also appears that there were new chassis for earlier cars, but these retained the old numbers—just to make the historians work harder!

Photo: Pete Lyons – www.petelyons.com

Chuck Parsons…Sticking with Lola

As the 1969 Can-Am opened at Mosport, Parsons drove a Haas-entered T162 to a 5th–place finish behind Bruce McLaren; then with a new T163 for St. Jovite, he took a superb 3rd behind the two works McLarens. At Watkins Glen, where a second T163 appeared in the hands of Ronnie Bucknum, Parsons again ran 5th. A pair of T160s and a T162 were also entered, though none of the Lola drivers besides Parsons finished. Chuck failed to finish at both Edmonton and Mid-Ohio, where another T163 was entered for Mark Donohue, but it also retired. At Road America, Parsons again ran 3rd, just ahead of Peter Revson in yet another T163, while Donohue did not appear. The Haas entry took 8th at Bridgehampton, 6th at Michigan International, 3rd at Laguna Seca, and 2nd at Riverside, though the T163 for Riverside was a new car with stiffer tub and revisions to both suspension and bodywork. In the season finale at Texas International, Parsons finished 5th, earning the 3rd spot in the final points behind the two McLaren men, best of the rest and surely the best Lola driver.

The 1970 Can-Am season was scheduled to open at Mosport on June 14, but less than two weeks before, Bruce McLaren was killed while testing his latest M8D. That was a body blow to everyone in Can-Am, but didn’t stop Hulme and Gurney from putting the new car on the front row at the first race. Five T163s populated the grid, but Gurney won, with Dave Causey the highest-placed T163 in 7th. Parsons had not been entered for Mosport, and as soon as the season’s second race, it was clear that the T163 was no longer competitive.

For the next round at St. Jovite a new Lola, the T220, had arrived for Peter Revson to drive. He qualified 7th but retired, while the highest T163 on the grid was Parsons (15th), who drove well to finish 8th. Revson could qualify the T220 well up the grid, but couldn’t regularly get it to the finish, although he did manage to finish 2nd at Mid-Ohio and then take 3rd at both Donnybrook and Laguna Seca.

Parsons was usually the fastest qualifier of the T160 variants, but great results weren’t forthcoming, and he ended up 14th in the championship. For several of the privateers, however, the reliability of the car kept up their enthusiasm.

T160/9…the History

Photo: Pete Lyons – www.petelyons.com

To say that the car featured here has an interesting history is a bit of an understatement. When current owner Tom Walker offered Vintage Racecar the chance to test it, he was still tracking down the provenance, and some of that has emerged as this was written.

As noted earlier, the T160 series cars have not been all that easy to keep track of. This particular car was imported by Carl Haas, but Walker said he hadn’t been able to trace the first owner. Some serious searching, however, indicates that this was the car owned by Haas himself and entered for Parsons with Simoniz backing in the 1968 season. With this car in original T160 trim and carrying race number 10, Parsons scored a best finish of 4th at Las Vegas, but it also carried him to 5th at Edmonton and 11th at Riverside, although he did fail to finish at both Road America and Bridgehampton due to engine trouble, and Laguna Seca when a wheel came off.

The Parsons-Haas association continued into 1969, again with Simoniz sponsorship, and for the first race, the car was a T162. For the next round, however, Parsons drove what was described as a new T163, and used that car for the majority of the season until getting another new car for the final two races at Riverside and Texas. According to John Starkey, the early 1969 car was T163/15, a new car built as a T163. This car had a Chaparral-built Chevy engine, but the monocoque was damaged by Parsons early in the season and seems to have been replaced by chassis T163/16, which may account for it being referred to as a new car. At the end of the year, this car was sold to Dick Durant, who raced it through 1973. While this car was being repaired, it is conceivable that Parsons again used T160/9, although he also seems to have been associated with T160/3 during the ’69 season.

So, what happened to T160/9 after 1968? Aside from its possible use as a spare by Haas/Parsons, late in 1969, it was eventually sold to Doug Shierson. For the Michigan-based Shierson, it became the vehicle for his first serious foray into motor racing as a team owner. His family owned the Beacon Oil Company and was also associated with Marathon Oil, whose name and logo appeared on the Lola. Shierson later expanded into F5000 (running Peter Gethin’s winning Chevron B25), Formula Atlantic (where his team won three championships in four years with Howdy Holmes and Uncle Jacques Villeneuve), and then IndyCars (with Arie Luyendyk winning the1990 Indy 500).

Shierson had the car rebuilt with T163 bodywork, and scheduled Parsons again to drive it in 1970, though the car seems to have been entered in Parson’s name that year. The car was referred to as both a T163 and T160/3, another confusing little addition. It was occasionally referred to as chassis number T160-03, which was incorrect.

So, in the striking Marathon Oil livery, Parsons reappeared in his original T160/9—now in T163 trim—for the second Can-Am round at Ste. Jovite. Parsons managed only 15th on the grid but kept the car going well enough to finish 8th. The team skipped the third and fourth races, reappearing at Mid-Ohio in August where his 4th place was the team’s best result so far. A week later at Road America, Parsons gridded 10th but the engine overheated and he retired on lap 37. At Road Atlanta, Parsons qualified 8th behind Vic Elford’s pole-winning Chaparral 2J, but the race victory went to Tony Dean in an underpowered Porsche 908, after everybody else fell by the wayside. Parsons struggled home 12th.

Photo: Mike Smith

At Donnybrook, Parsons qualified 10th, but the clutch failed after only 12 laps in the race. At Laguna Seca that October, he gridded the aging Lola 8th quickest on a circuit he enjoyed, and moved up to finish 6th. At the Riverside finale, the clutch again failed early in the race and that was the end of the car’s career—at least in Parson’s hands.

Life on the Road

At the end of the 1970 season, Shierson sold T160/9 to Otto Uecker, and it appeared in one more Can-Am race, at Laguna Seca in 1971 where Oliver Jones drove it and retired with an oil leak. Jones also contested a few SCCA races before the car was sold to John Erickson in 1972, and he ran several club races before passing it on to Frank Spaeth. During Uecker’s ownership, from ’71–’72, the car had been part of the fleet at the Quaker State Racing School, and after this duty, it received the small-block Chevy that powers it today. It seems that Frank Spaeth then did something fairly amazing, converting the car to road trim; and it was in this state that British classic-car dealer Rod Leach bought it in 1977, returning it to the UK.

The car had by then suffered a terrible purple, red, and yellow paint job, which was removed by AutoKraft; and after Allen Seymour refurbished the essentially original chassis, the bodywork was given a coat of pristine red. When Motor Sport magazine did a road test on T160/9 in August 1979, the tester commented that underneath the road gear, the car was still a pure race machine, with Hewland LG500 gearbox, race suspension, 25-gallon bag tanks, and Goodyear Blue Streaks.

Photo: Pete Lyons – www.petelyons.com

Rod Leach was well known in the period not only for the cars he sold—especially his ability to find Cobras—but also for hosting a monthly pub meeting at The Goat in Hertford Heath, which regularly attracted large numbers of exotic road and race machinery.

Leach sold the car to Alex Seldon, who converted it back to race trim, and ran it in the Atlantic Computers Historic GT Championship from 1983 to 1985. In 1986, the Lola was acquired by Peter Kaus for the German Rosso Bianco museum, where it lived for 20 years until that entire collection was sold. The current owner bought it in December 2006, and has lovingly returned it to its beautiful Marathon Oil livery from 1970.

Driving T160/9

I saw a number of Can-Am races in the United States and Canada in 1970–’71 but, in retrospect, not nearly as many as I should have. They were such great spectacles; I only wish I’d had the foresight then to go see them all because the days of big-banger sports cars were never to return, not in such numbers, with such seriousness, or with such great drivers.

Donington Park was a proper venue for testing this great car, even though we were using the “private” old loop. Still, it features uphill blinds, sweeping lefts and rights, a wooded area, the sensational downhill straight and following hairpin, and the uphill crest that gets cars airborne—all of which should do nicely. In addition to Tom Walker, Patrick Morgan was also on hand since his Dawn Treader Performance outfit, having done much of the work, was looking after the car. Patrick is, of course, the son of the late Paul Morgan, co-founder of Ilmor, and Patrick and his staff are all ex-Ilmor—a proper crew!

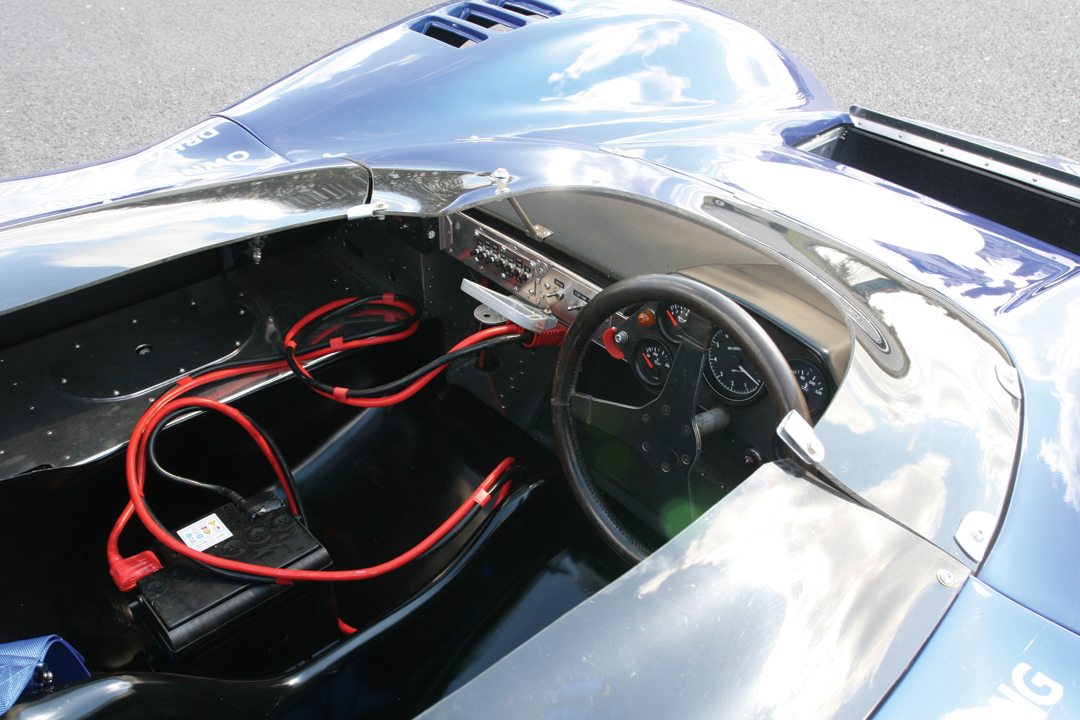

After a short briefing on starting procedures—getting the sequence of pumps and switches right, and finding the spring on the gear lever so I could find first gear in the Hewland 5-speed—time comes to fire up. With a few warming-up laps behind us, the engine note becomes more familiar, but instead, the throbbing/thumping one might expect from the eight- or nine-liter big blocks, this one zaps a sharper, raspier tone out the exhausts. The cockpit is spacious and the instruments simple; oil temperature and pressure gauges to the left, rev counter in the center, and water temperature and fuel pressure gauges to the right.

As expected, everything is totally functional and the pedals are well spaced with a very large brake pedal. Now, why would that be? Rear vision, at least at low speed, is fine, though it would be less so with the huge wing that was fitted at one time. At speed on a bumpy track, there was always an incentive to keep going quickly, because you might struggle to see what was behind you anyway!

Once warm, the gearbox is no longer a tussle, and later listening to Tom Walker driving it much harder than me was evidence as to just how well that box worked. The big tires— Dunlop Racing 4.30/11.60-15 on the front and 5.30/16.00-15 on the rear—warmed up pretty quickly, and once there was heat in the rubber, it was possible to push a little harder. The team had felt there would be notable understeer, and that seemed to be the case, though it didn’t seem too bad. The real issue with this car is that it gets from one corner to another very quickly, and that means learning to control the acceleration and the braking.

On the Donington “loop,” it’s second, third, and fourth downhill in very rapid succession, but the hairpin is at the bottom, so a lot of effort goes into finding the balance. There is no point in having to slam on the brakes because the car is going to run wide and understeer— better to back off, go easy on the brakes, ease it through the corner, and use all that power once it’s straight again. There is that great blind crest at the top in fourth and then the fast left bend. The torque is most evident here, pulling hard in fourth, a sweep around to the right, all that torque again this time and third. The real grunt is so apparent. There’s a slight tweak to the left, no braking, then a very fast right as you head for the top of the hill, picking up a bit of understeer out toward the Leicestershire countryside, and then flat on down the hill.

Though Walker and Morgan are pretty hard on themselves and keep looking to improve it, the car seems very well balanced and agile to me. It’s not the brute I expected. I drove Brian Blain’s T163 in California a while back, which was, I believe, Parsons’s spare car for 1969. It had 9 liters and 900 horsepower—unbelievable! This car is quite civilized.

After the run, Patrick Morgan told me a bit about what had happened to the car, which came to him with many of the road components still on it: “We have had to re-manufacture some of the suspension components which were badly corroded internally. The wiring loom was configured for the road, so that was replaced. The flywheel on the car protruded about four inches below the bottom line of the car, so that was changed and the clutch then had to be matched to that. The engine and gearbox were rebuilt and most of the plumbing replaced. Most of the engine is original, although the block itself is not. One of the liners was cracked and the original block was quite a nice period piece. The heads are original, as are all the internals. The engine had been last rebuilt by Mathwall, and had a rare injection system with slide throttle and crossover trumpets. The clutch pedal is still a hangover from the road setup, so we are working on that, too. We are learning a lot about the car as we go.”

Buying and Maintaining a Can-Am Lola

One of the positives about cars like the Lola T160 series is that they were “straightforward,” built mainly for privateers, which meant that design ideas had to consider ease of maintenance and access to spares. Because the T70 became and remained so popular, spares for those and the T160 series are not impossible to find, but the mechanics in the period protested about races being run on consecutive weekends because they felt, very strongly, that the cars needed to be stripped after every race and checked. The big engines created enormous vibrations that tended to loosen lots of parts. The works teams could manage this, but smaller operations struggled to rebuild their cars between weekends, so this had an influence on the timing of races.

Given the means to do proper maintenance, this period Can-Am car is not overly problematic. Engines and engine parts are readily available, especially in the United States, so the opportunity for very exciting, high-speed racing is there for a relatively modest investment. The cars are there, but the price is entirely dependent on history and the condition in which they are found. As this is written, there is a T160 on the market in the United States for $165,000, though they have appeared for substantially more.

Specifications

Chassis: Monocoque high-strength alloy

Body: Spyder with T163 panels

Wheelbase: 94 inches

Track: Front 56 inches; rear 53 inches

Weight: 1480 lbs/670 kg

Engine: Chevrolet Iron Block

Displacement: 5.0-liters

Power: 475 bhp at flywheel

Carburetors: Slide throttle, mechanical injection

Gearbox: Hewland LG 500 5-speed

Steering: Lola rack & pinion

Brakes: Girling 4 pot calipers, 11-inch ventilated discs, 1.1-inch thick

Wheels/Tires: Dunlop Racing: Front: 4.30/11.60-15; Rear: 5.30/16.00-16

Suspension: Front: Double wishbones, coilover springs. Rear: Lower wishbone, top links, coilover springs

Resources

Many thanks to Tom Walker and to Patrick Morgan and his team.

P. Lyons. Can-Am. Motorbooks International USA. 1995.

P. Lyons. Can-Am Photo History. Motorbooks International USA. 1999.

J. Starkey. Lola T70: The Racing History & Individual Chassis Record. Veloce Books UK, 4th Edition. 2008.

www.WorldSportsCarRacing.com