The Morgan Motor Company

With no thoughts of cars in mind, I first visited Malvern in the high summer of 1962, arriving by train after a three-hour journey from London on an oven-like day in June. It all seemed like the poem Adlestrop, as nothing stirred. Little did I know then that this was the home of one of the world’s most consistently idiosyncratic motorcars and that today, 53 years later, it would still be proudly independent.

In fact, its independence was a contributory factor to one American writer’s opinion, in 1960, that the Morgan exemplified two facets of British national character, “disregard for what the rest of the world may be up to, and loyalty to a proven pattern of simplicity.”

Photo: Peter Collins

There are those who might consider the latter observation to be a detriment to the Morgan car in that the company seemed never to develop much beyond its first instincts and made use of the same dynamics for many years. On the other hand it was proven, over and over again, that there were many thousands of potential customers who were only too pleased to offer considerable amounts of cash in order to be placed not only on the company’s notional order list, but even simply on their waiting list, such was the appetite for a vehicle that not only looked traditional but was traditional—and still is.

It all started in 1909, when Henry Frederick Stanley Morgan built his own car. He had been employed by the Great Western Railway, a job which, if not prestigious, would have been held in considerably higher esteem than the equivalent today. In 1902, he had bought himself his first car and in 1904, he left the GWR in order to establish a motor garage and motorcar sales outlet in Malvern Link. There he obtained a thorough grounding in motor engineering, in particular building up plenty of practical experience in an era when that commodity was vital if one was to venture out onto roads that were mostly unmetalled.

By 1909, he was confident enough in his abilities to build himself his own car. This was three-wheeled, with two steering at the front and the driving wheel at the rear. This was not an unusual choice of layout as there were many tricycle cars available at the time, their niche being that of economical motoring.

Photo: Peter Collins

Drive to the rear was by chain and the front suspension consisted of independent sliding pillars on each side. These consisted of exactly that, a sliding pillar with special spiral springs and steering dampers. The only other company to employ this method of springing was Lancia, so they were in good company. It was so successful that the method was still in use on Morgans into the 21st century.

HFS had only built the machine for his own use but, by all accounts, many who saw it requested that he build them a replica, the upshot being that, in 1910, with financial and moral support from his father, a local minister, the Morgan Motor Company was created with premises also in Malvern Link, at the foot of the Malvern Hills.

He applied for patents that year based on drawings that were supplied to his order by a John Black, who was later to become boss of the Standard Motor Company. By 1911, he was building two-seater versions of his original and entered competition successfully for the first time the next year, 1911, in a reliability trial. These cars utilized a two-speed gearbox with no reverse, a practice that continued for many years.

The competition history grew stronger when, in 1913, HFS broke the 1100-cc one-hour record, completing just less than 60 miles in that time, while over in France, one of his cars beat several four-wheelers to win the Cyclecar Grand Prix d’Amiens.

Photo: Peter Collins

Performance three-wheeled Morgans became popular for a while after the cessation of the First World War. These included the Aero and the first incarnation of the appellation Super Sports. By 1925, a special streamlined model was timed at more than 100 mph over a kilometer, and five years later a racing model was officially timed at over 100 mph for one hour.

Despite all of this however, Morgan was fighting an uphill battle against the four-wheeled opposition, in particular MG. At last, in 1931, the company adopted a conventional three-forward-speeds-and-reverse gearbox for its tricycles and made available the F4, Family Four seater, which utilized Ford’s ubiquitous 1172-cc side valve four. None of this was enough to stem the tide, however, and although three-wheelers stayed in production until 1950, they were by then obsolete.

The company’s savior arrived in the form of its first four-wheeler named 4/4 denoting four wheels and four cylinders. Exhibited at both the Paris and London Motor Shows in 1936, the model initially utilized an 1100-cc, four-cylinder Coventry Climax engine. Suspension was by the tried and trusted sliding-pillars at the front, with live rear axle and semi-elliptic springing at the rear. Worm and peg steering guided the way, and the chassis was tubular with Z-section side members. Capable of 75 mph and enjoying good handling, it was a competent little sportscar.

Later, in 1939, the Standard motor company built special 1267-cc versions of their “9” engine for Morgan, but it was with the Climax engine as motive power that Morgan made its first appearance at Le Mans, in 1938. Handled by Miss Prudence M. Fawcett, one of six women in the race, and Geoff White, the little car achieved 13th overall out of 15 finishers. White was back again for 1939, this time with the engine slightly enlarged to 1104-cc. With “Dick” Anthony co-driving, the car went nearly 180 miles farther to finish 15th overall out of 20.

Once WWII was over, the 4/4, still with the Standard engine, continued production in Malvern alongside the three-wheelers until 1950. In ’51 a new car called the Plus 4 debuted, still powered by Standard, but now utilizing the 2088-cc, four-cylinder that was usually found in the parent company’s Vanguard. The 4/4 model was dropped until 1955, when the title was resurrected for a new model that relied, at first, on Ford’s venerable 1172-cc, side-valve unit.

Meanwhile, a Plus 4 had been entered for Le Mans, in 1952, by R. Lawrie, who had previously driven Jaguar, Riley and Aston Martin cars at La Sarthe and he was to share with J. Isherwood, but it fared badly and they were out of the race within three hours with water pump failure. In that same year, the Plus 4 was transformed by the adoption of Standard Triumph’s 1991-cc, four-cylinder TR engine, and the model subsequently benefited from each upgrade to those units, receiving the TR4 2138-cc engine from 1962.

In turn, this unit was replaced by the Rover (nee Buick) V8 in 1968. Weight was little different and the new Plus 8, as it was christened, was a trad-Brit AC Cobra in performance. Constant upgrades were performed on this power unit until BMW was contracted to supply engines of similar configuration to bring the model’s power train into the 21st century. As is the case with all manufacturers, a plethora of various niche models have been introduced in the last 25 years, expanding the range to the point where HFS would find it hard to recognize the company he started, except for the cars’ traditional profile, which never palls. An attempt to bring the company up to date in 1963, with the Plus 4 Plus fiberglass coupe, was a mistake and failed mainly because those who want a Morgan want it to look like a Morgan. If they didn’t, they would go elsewhere.

Chris Lawrence and racing into the ’60s.

Towards the end of the 1950s, after the introduction of the rugged 2-liter TR unit, a young man by the name of Chris Lawrence began making a name for himself in the UK conducting Plus 4s at tremendous speed in national racing. In 1959, he won the Production Sports Car Championship winning 19 races out of the season total of 22. All of these were in a Plus 4, modified and tuned by himself. At the end of the year, Chris and three others in the team, set up LawrenceTune in Acton, London W3 and, as well as dealing in Triumph engines, the company also diversified into Formula Junior and built the Deep Sanderson cars, which included three sports prototypes.

Morgans were continually developed and, in 1961, an entry was made for that year’s Le Mans 24 Hours, but it was turned down by the Automobile Club de l’Ouest on the grounds that the car was “old-fashioned and therefore dangerous.”

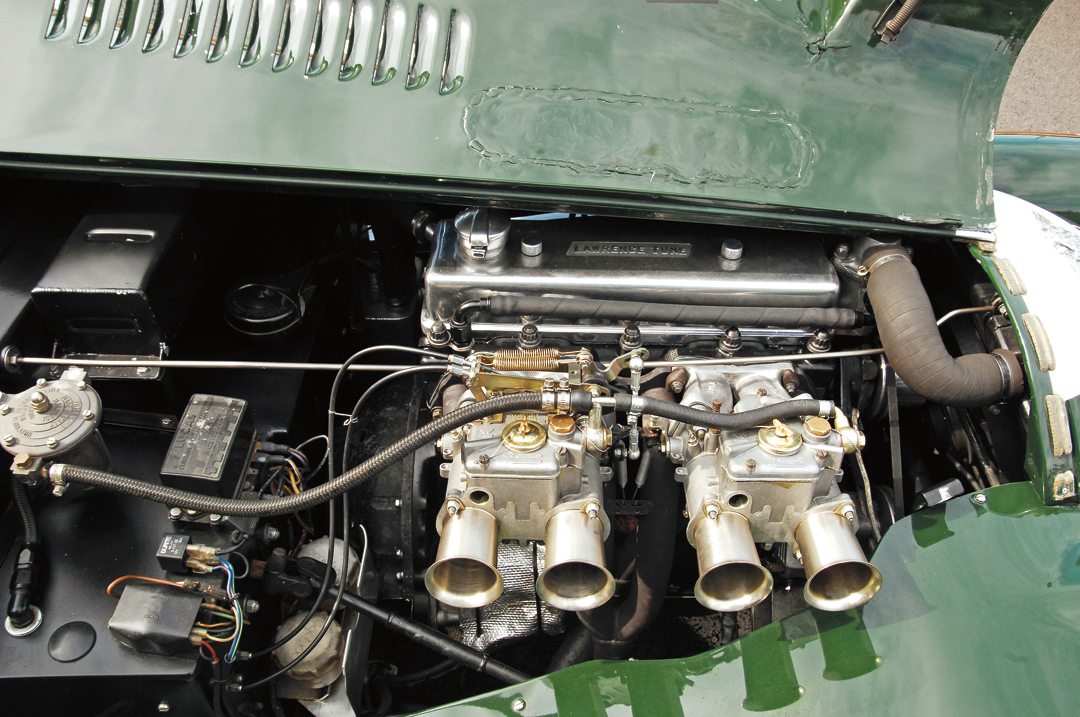

Like a red rag to a bull, Lawrence entered again for 1962 and comfortably got into the race. The car was registered TOK 258 and it won its class while finishing 13th overall. By this time Lawrence had established a serious relationship with the Morgan Motor Company, so successful was his car and those that he prepared. The result of this tie-up was that Morgan introduced a new range-topping model named the Plus 4 Supersports, resulting in Lawrencetune producing 400 modified Triumph engines in total for the model, Morgan having sold 101 of them by the time the model was deleted. The Acton works’ high level of modification had managed to increase power from Triumph’s 2138-cc engine factory specification of 92 bhp to a total of 120 bhp, and Morgan sold them under guarantee.

These figures were achieved by the use of an Iskenderian camshaft, two twin-choke Weber carburetors, a tuned inlet manifold, four-branch exhaust system and a gas-flowed cylinder head. Chris later went on to advise Morgan on their Aero 8 model and return to Le Mans in the 21st century.

XRX 1

Philip “Pip” Arnold had been a keen Morgan owner/driver and part of the Lawrencetune team for some years when he decided to sell his 1956 Plus 4 and buy a full specification Supersports with the sole intention of racing it.

The factory in Malvern dated its despatch as April 9, 1963, with a very full specification. The chassis number was 5356 and engine number LT 1. The car was liveried Westminster Green and registered XRX 1. This number had come from the Morgan originally bought new by Richard Shepherd Barron that had been turned down at Le Mans in ’61. For ’62, it was rebuilt with all new bodywork and re-entered for La Sarthe, but Chris Lawrence wanted to retain his TOK 258 number so the registrations were swapped with Pip Arnold’s car, then carried over to the latter’s new example. It was right-hand drive with 72-spoke wheels and disc brakes. A 16-gallon fuel tank was fitted with dual fuel lines and fillers. The body was aluminum, as were the fenders. It had an undershield, bucket seats and a hard top. The fillers, undershield and top distinguished it from a normal Supersports, so it was a very special example for racing.

XRX entered the fray almost from the moment it could turn a wheel, as it was run in the Sussex Trophy for GT cars at the big Easter Goodwood, interestingly held on March 30, some 10 days before the published factory despatch date! This is not to suggest any problems with the car’s provenance as there are photographs of it in the paddock at Goodwood that weekend with TOK alongside. The event was won by Graham Hill in the lightweight E-Type 4 WPD, and John Surtees was 2nd in a Ferrari 250 GTO. Pip sadly retired midway through the race.

Not much more than a month later the team went to the daunting Spa road circuit—complete with the Masta Kink in those days—for the 500 Kilometers on May 12. With factory Ferrari 250 GTOs occupying the front row of the grid, it was clear that this was a race of considerable importance and it would be the first time Pip and the new XRX had raced abroad. All was well though, as XRX came home 10th overall and 2nd in class behind Lawrence.

This was all very well, but only two weeks later came an even more difficult proposition—taking part in the Nürburgring 1000K World Sportscar Championship race. Only days separated the two races, and in the rush normal preparation had to be reduced to simple servicing, with the result that during first practice on Friday, XRX came to a halt with serious engine maladies. The required parts were not available within the team so Len Bridge, chief mechanic back at Lawrencetune’s Acton, London base, had to fly out to Germany with the parts to rebuild the defective unit. An all-nighter resulted in the engine being fired up at 8:15 on Saturday morning, which gave the team just enough time to run it in, practice and, finally, qualify, all before the end of track time that day.

With Robin Carnegie sharing the driving, XRX led its class for a long while during the Sunday race, only finally having to relinquish the position to teammates Braithwaite/Slotemaker in another Morgan due to XRX’s hardtop coming loose. This problem having been fixed, Pip and Robin drove well to bring XRX back to 2nd in class at the finish.

Through the rest of 1963, Pip campaigned the car in the UK and at the August Bank Holiday Brands Hatch Guards International meeting the combination scored a 9th place overall in the John Davy Trophy GT race, taking 3rd in class.

Sadly, however, it was becoming clear that at the international level something drastic needed to be done to the car to enable it to remain competitive into 1964 and beyond. The obvious, strongest and then-current opposition consisted almost entirely of Porsche, which had introduced its 904 with lightweight body/chassis and four-cam engine. But, it wasn’t only Stuttgart that Morgan needed to be worried about on track. Cheshunt was now becoming more than just a threat with its light, powerful and good-handling Lotus Elan.

The upshot was that Chris Lawrence sat down and designed the SLR, a streamlined sports GT based on the Morgan chassis and Triumph Supersports engine, but it needed money and development and Pip realized that the reality was that in order to continue at the right end of the field in international GT racing he would have to go for a Ferrari or Porsche, neither of which he was prepared to spend the money on, so XRX was put up for sale and Pip decided to retire. Sadly, he passed away a few years ago.

The Hon. Basil Fielding became the car’s new owner and was soon out on track with it, but at the national level. The first thing he found was that the chassis had suffered some wear and tear during its 1963 racing season and he solved the problem, to save the time and expense of repairing it, by simply replacing it with a new one, stamped by the factory as 5471. Despite this, XRX can be considered to have a continuous history. Especially, as the number 5356 was never reused.

So XRX set out for a new life in UK national motorsport being raced occasionally, such as at Silverstone in March 1964, but also hillclimbed, and I recall seeing it at Prescott in the latter half of the 1960s. For the latter discipline, a little more power and torque was desirable, so Fielding had the Triumph “four” replaced with a Daimler 2.5-liter V8, as used at the time in the SP 250 sports car.

This was an enticing transplant, as the gem of an engine both revved well, developed 140 bhp and was light and compact. Others went down the same route at the time, most notably with TVRs.

Eventually, XRX was sold to Jorg Westphal in Germany, who campaigned and maintained the car for many years, always retaining the V8 until it found its way back to the UK via Morgan racer Keith Ahlers, who arranged for XRX to be rebuilt by marque specialists Brands Hatch Morgans. It was found that the Daimler V8 was still in the car, so the restoration, carried out meticulously by Brett Syndercombe and Rick Bourne, included the installation of a Lawrencetune specification TR4 2138-cc four-cylinder unit.

Purchased by the father and son team of Gabriel and Dion Kremer, the car often runs rings around more powerful opposition today, and has completed seven years of historic racing without a single failure.

Driving XRX 1

Once you have contorted your body to fit the narrow aperture offered by the car’s door and A-pillar and settled yourself into the period-style seat, your view ahead is dominated by the long hood in front of you, complete with the fenders and louvers. The cockpit is neatly appointed with the traditional-style seats and period dashboard with all necessary gauges. Engage the starter and the TR unit splutters into life, the big double-choke Webers soon even out as the big four clears its throat. The gear lever is to hand, almost perfectly positioned on top of the gearbox, and first is just a short, mechanical move to the left and up.

The clutch is traditional British sportscar in that it is not that light, but the car responds immediately and moves off in an almost sedate manner which belies the available performance once out on the track, when she gives you the first hint of her performance pedigree.

As you squeeze the throttle harder, the engine note rises in pitch from the four-cylinder burble to a whine that is almost jet-like. You need to take the car up to 7000 rpm to gain full performance on track—a high figure for a large four-cylinder with three main bearings—before you release the clutch for the next gear. XRX pulls well through all four forward gears and then you’re approaching a braking point. I tap the pedal to ensure it is there before applying a not inconsiderable amount of leg muscle to slow the car down—shades again perhaps of its traditional British sportscar pedigree.

The brake setup is discs at the front and drums at the rear, and the car reacts perfectly to the pedal; a little too much pressure and you can hear a tell-tale chirp on asphalt from the rear. Too little and you overshoot your braking point!

Release the brakes, feather the throttle to ensure that the car is under control and point the long hood toward the apex. Those front Dunlop cross-plies, way out in front, bite immediately as they respond to the steering input. Sensing there is more speed to be had you apply more throttle, but now the tires have reached the limit of their adhesion and the result is an initial build-up of understeer. Lift the throttle a little until you feel the car respond to the steering, then apply a sharp burst of throttle and apply steering lock simultaneously. This results in immediate oversteer. This is not the sort that gives you a kick, but rather it’s a gentle warning about what might happen so you have time to counter with some opposite lock. Now the car is perfectly balanced and will happily negotiate the bend to the apex and beyond with only minimal throttle adjustments.

Needless to say this is not always the fastest way around a bend, but XRX almost wills you to drive this way, such is the ease and satisfaction of doing so. The car will just as happily respond to a more conventional approach, maintaining traction throughout the bend.

Back in the pits, on exiting the car, it is apparent how far back you sit in the chassis and this may well help to explain the benign manner in which XRX treats its driver.

A number of marques or models have been described over the years as “giant-killers,” chief among them Colin Chapman’s Lotuses due to their extreme lightness. Weighing the FIA regulation weight of 850-kilograms this Morgan tips the scales a little on the heavy side, but with 180 bhp coupled with the sheer maneuverability and handling, it more than makes up for this.

As we have seen this “little green gem” was capable of mixing it in period with the Ferraris and Cobras and it still is. It may lose the advantage down a long straight, but it is capable of catching them and out-cornering them come the twisty bits, occasionally outrunning them to the finish line.

Someone once said that, “it is only the move toward conformity at Morgan that goes slowly.” Having enjoyed this traditional sportscar from a host of angles, I say a traditionally British “three cheers” and who needs conformity anyway?

SPECIFICATIONS

104 of all types built.

Construction: Steel tubular chassis. Z section side members. Ash wood frame for alloy bodywork.

Engine: All-iron ohv four-cylinder of 2138-cc displacement with oil cooler. Twin double-choke 42DCOE Weber carburetors with hood scoop for air intake.

Max power: 125bhp @ 5500rpm.

Transmission: Four-speed manual plus reverse; driving rear wheels.

Suspension: Front: Independent by sliding-pillars. Rear: live axle, leaf springs.

Steering: Cam and lever.

Brakes: Discs at front, drums at rear.

Length: 3683 millimeters

Width: 1422 millimeters

Wheelbase: 2438 millimeters

Weight: 850 kilograms

Top speed: (Road) Approx. 120mph. 0-60mph (road) 7.5seconds.

Resources / Acknowledgements

With many thanks to Gabriel and Dion Kremer for letting us use their car for this feature and for their help in compiling it.