News of a powerful new alliance in the automobile world broke in June of 1920. One of its constituents was the Sunbeam Motor Car Company, founded in England in 1905. In 1909, it acquired a new designer and chief engineer, Frenchman Louis Coatalen. Another participant in the alliance was A. Darracq & Company. Previous combinations found it producing autos under the Talbot marque in Britain and Darracqs in France—to simplify a highly complex train of events—their 1920 combination was STD Motors, of which Louis Coatalen was director of competitions.

Traditions of all three STD marques strongly supported motor racing as a means of promoting their merits. Coatalen immediately began preparing for the 1921 racing season, in which both the Indianapolis 500-mile contest and the French Grand Prix were run under a new 3.0-liter capacity limit. Here was a heaven-sent opportunity to flaunt the skills and performance of all three of the company’s marques by building a single, new type of racing car to compete under their various badges. The company’s racing also had internal benefits to Coatalen as Sunbeam historian Anthony Heal explained:

“Racing has more than just technical value and to the Sunbeam company it was the mainspring of their endeavor. To Louis Coatalen it acted as a spur and the hundreds of men he employed felt an intense pride in the success of the Sunbeam racing cars. So long as Sunbeams ‘wore the green’ in international Grands Prix every man was ‘on his toes’ and the firm retained its technical leadership. The same applied to the Talbot and Darracq marques.”

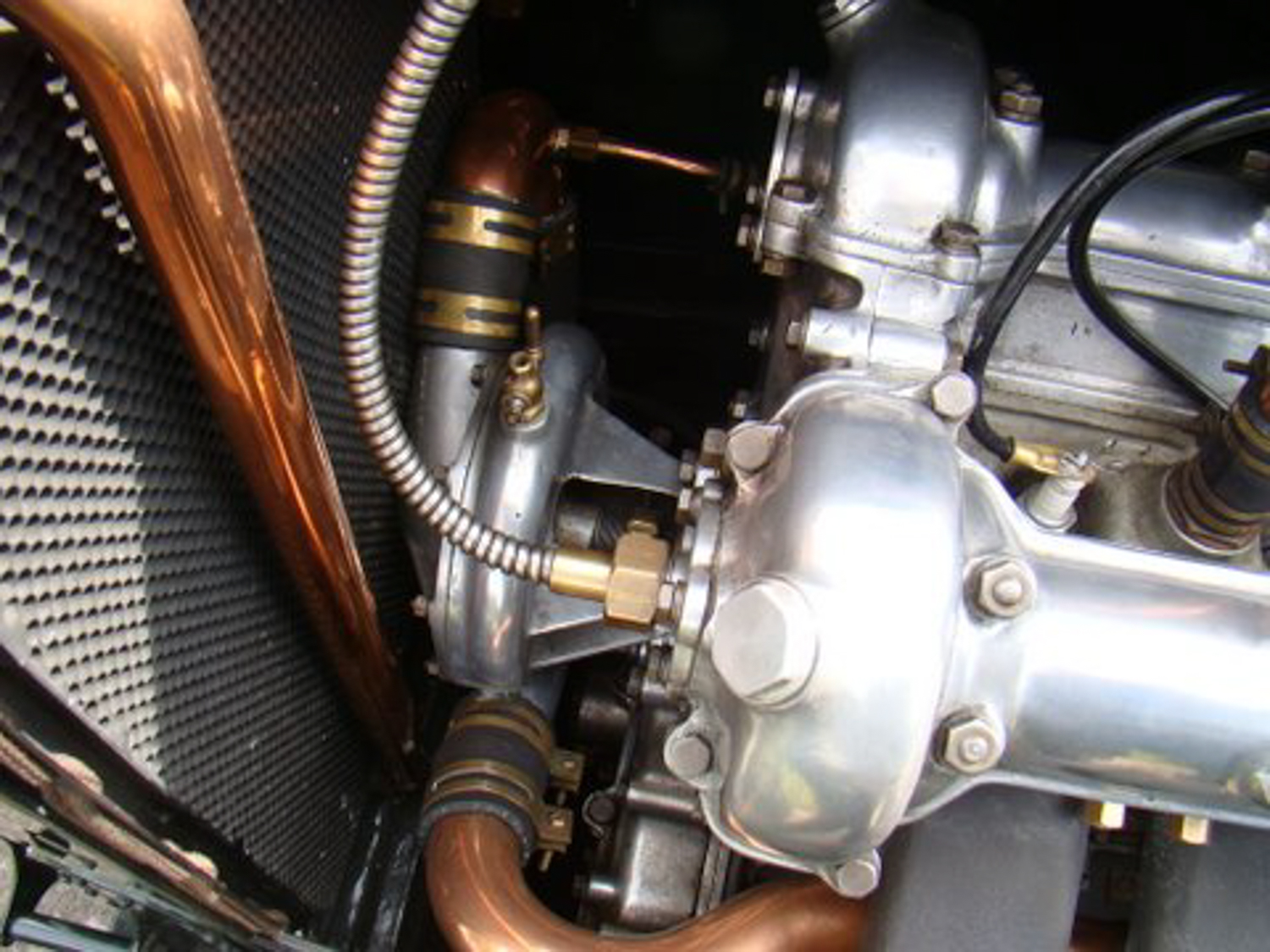

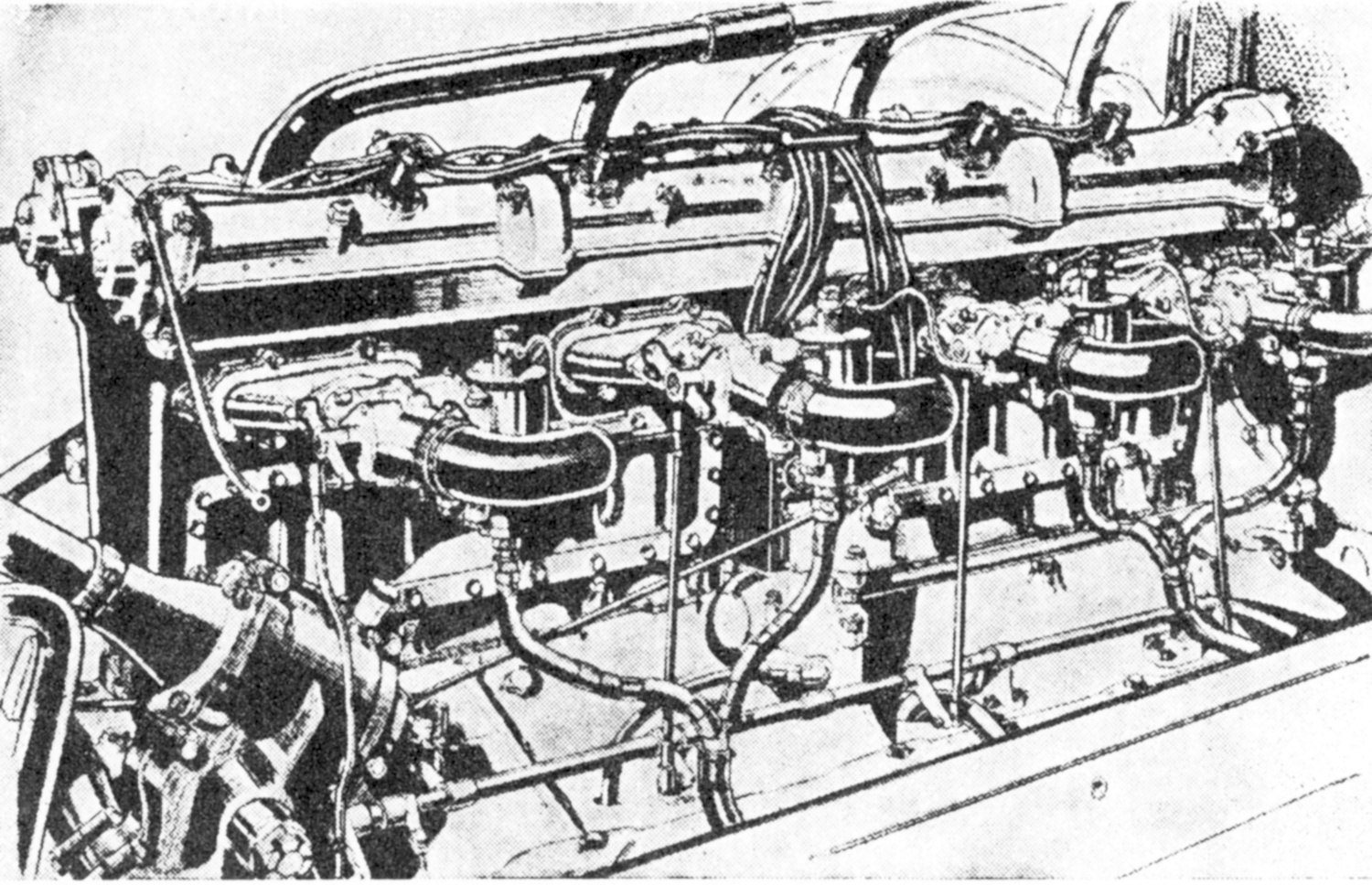

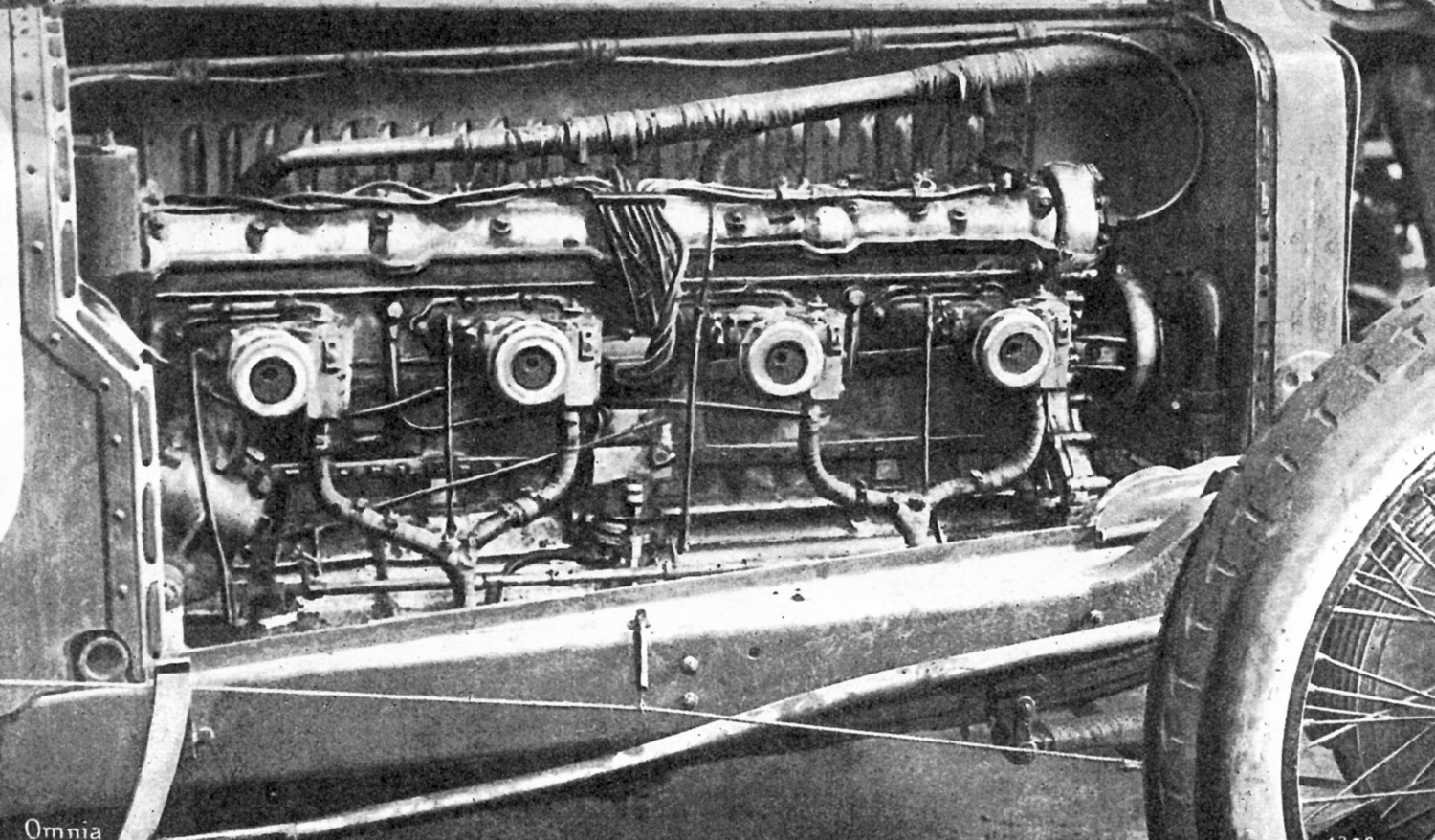

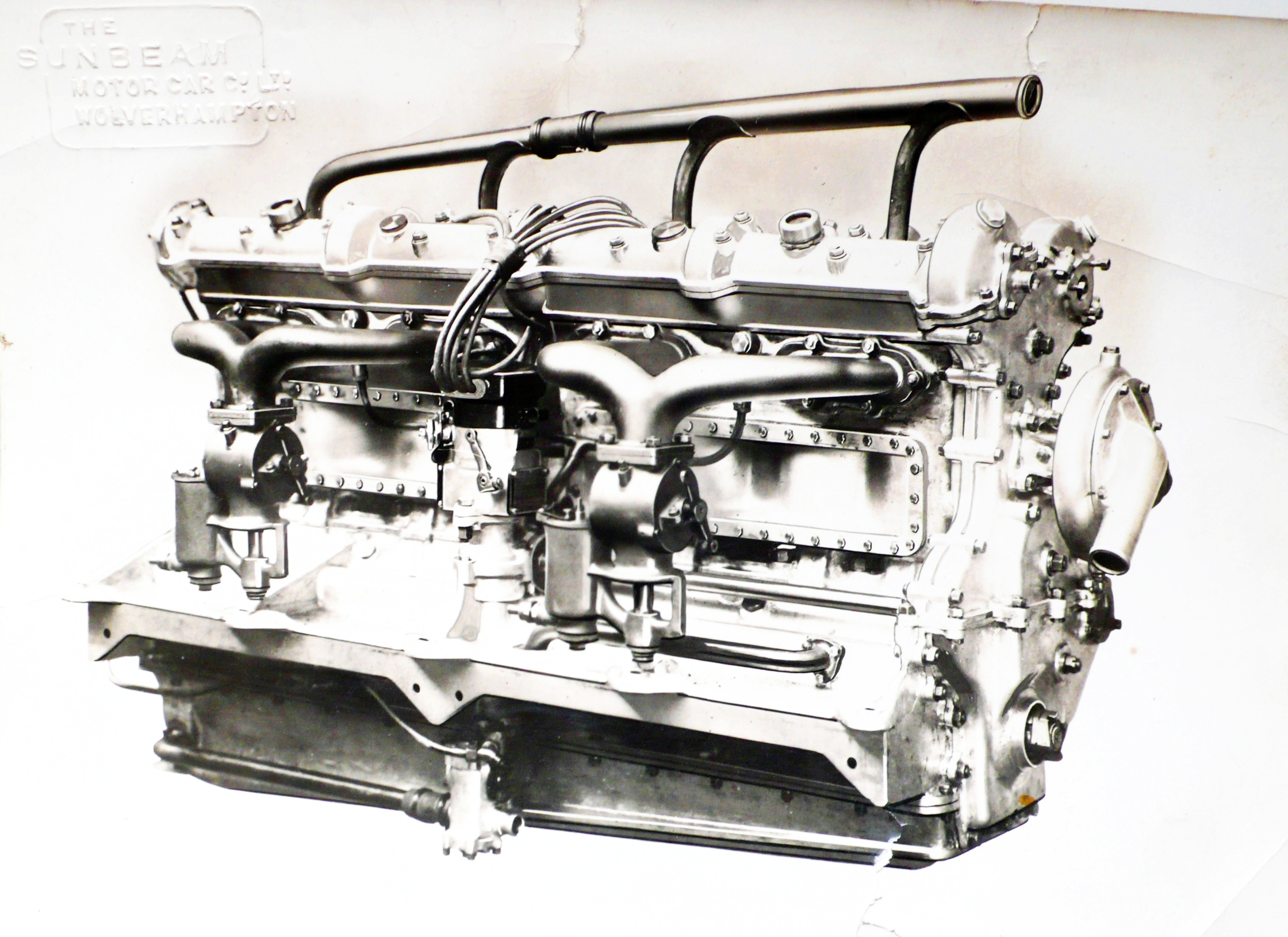

Among the entries for the 1921 season, wrote historian Laurence Pomeroy, Jr., “the Sunbeams (or Talbot-Darracqs) were highly interesting. They were the first completely post-war racing models for which Louis Coatalen was responsible and there was no doubt that his team of designers modelled the engine fairly closely to the successful 1920 Ballot. The timing gears and camshaft layout were very similar, the bore and stroke (65 x 112 mm) identical. But four carburetors were fitted and owing to the use of plain, in place of ball, bearing mains the cylinders were more widely spaced and the engine was longer.”

Designed by ex-Fiat man Edmond Moglia, the STD eights had cup-type tappets and two blocks of four cylinders cast in aluminum with dry steel liners—a technique Sunbeam perfected in aero engines. Output was 108 bhp at 4,000 rpm while peak torque was reached at 3,500 rpm. Veteran-car expert Cecil Clutton commented on the eight’s smooth torque characteristic above 2,000 rpm:

“In this respect the Sunbeam differs from the 1921 GP Ballot which had a more flat-topped power curve, peaking at 3,300 rpm as against the 3,800 rpm of the Sunbeam. As a result the Ballot, which was also lighter than the Sunbeam, was able to pull both higher and more widely spaced gear ratios. Since 4,000 rpm on the Sunbeam represents a piston speed of only 3,000 feet per minute, the engine could be driven practically without reserve.”

Clutton also remarked on the Sunbeam’s crankshaft layout, which like the Ballot was the classical 4-4 type. “The arrangement is particularly favorable to gas distribution from two carburetors,” he noted, “but is subject to an unbalanced couple which is said to produce excessive crankshaft vibration. Tests conducted by Sunbeam showed that maximum vibration occurred at 1,750 rpm, which is in any case outside the speed range usually employed. Moreover, it is quite undiscernible when driving the car.”

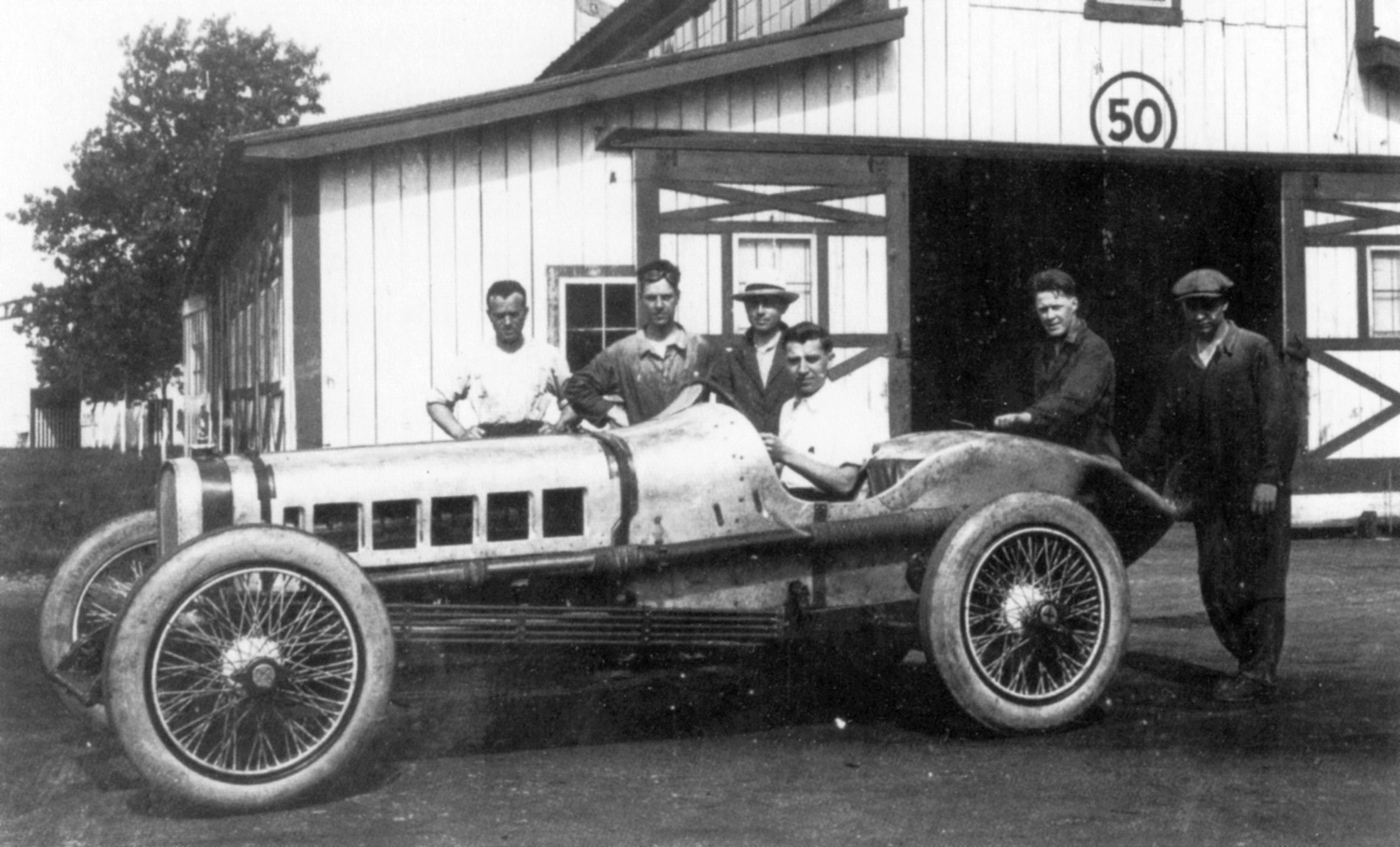

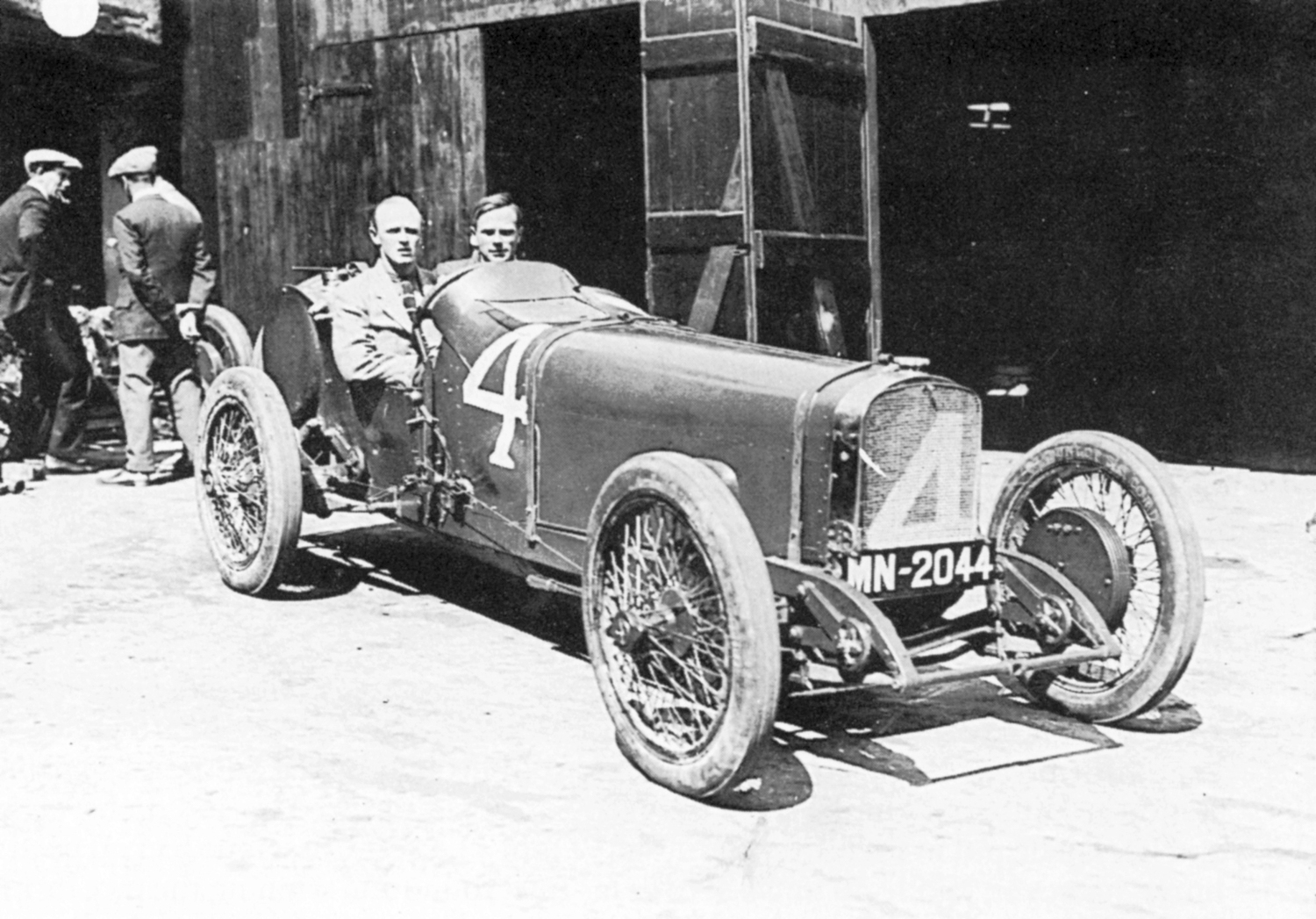

“On 3 November 1920,” wrote historian Robert Dick, “Coatalen ordered four chassis and seven engines for a new three-liter Sunbeam racer. On December 14, 1920 and April 20, 1921 he ordered two additional engines. At the same time, at Suresnes, the original location of the Darracq factory, three identical cars were assembled as Talbot-Darracqs. Total costs were estimated at £50,000.” Three cars were booked to race at Indianapolis and the rest allocated to the French Grand Prix.

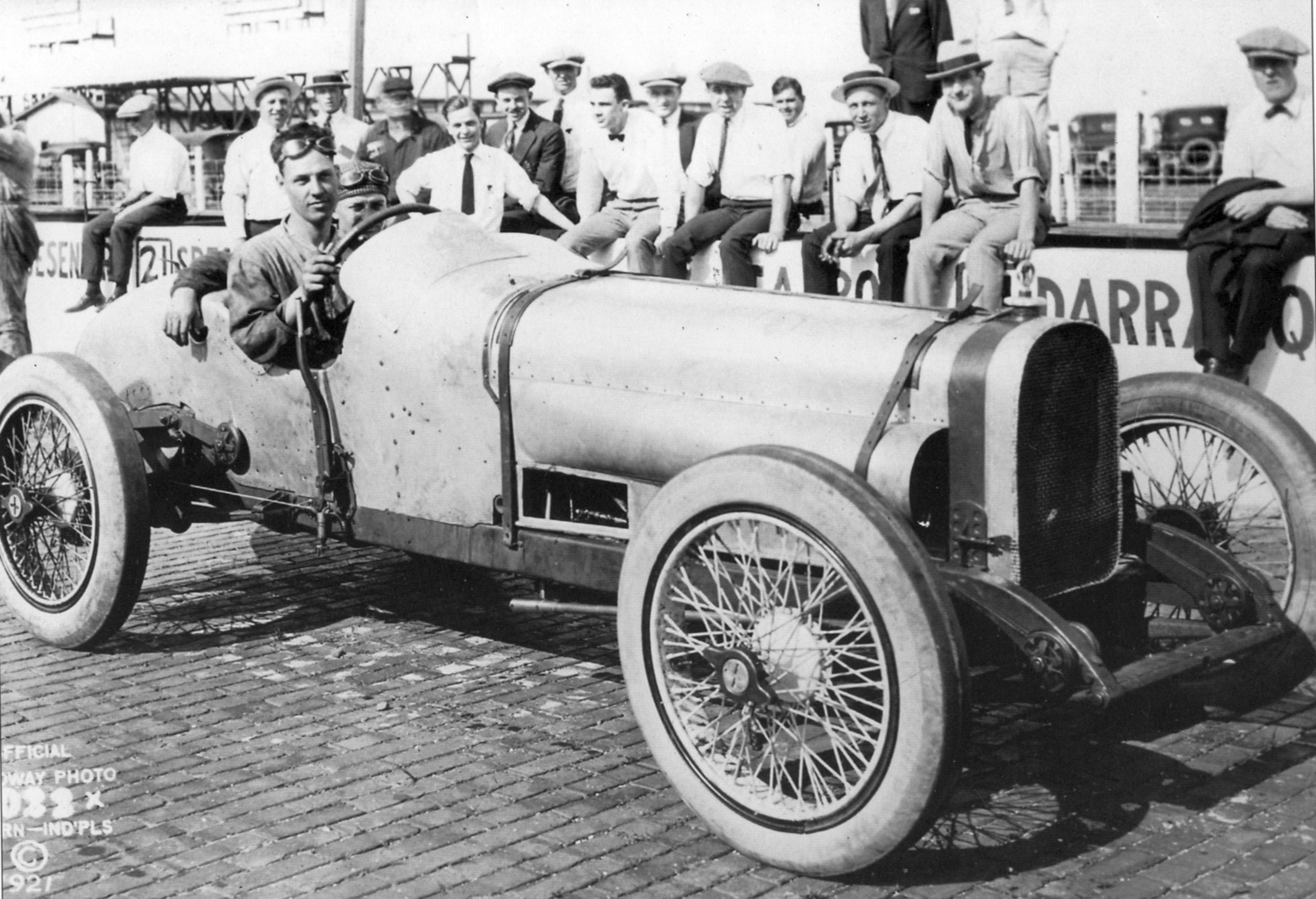

Showing their hand first in America’s 500-mile race on May 30th, two were “Sunbeams” and one a “Talbot-Darracq”. “At 350 miles two STD cars were lying third and fourth,” related Pomeroy, “but various incidents intervened and eventually the best that could be managed was fifth place at 84 mph, over 5 mph slower than the winner’s average of 89.72 mph. Five out of the first six cars had eight-in-line engine, which type also contributed 90 per cent of the finishers.”

The race was a powerful resurgence by the Americans against the European invaders, the Sunbeam being the only overseas entry to complete the 500 miles, and that in the hands of American driver Ora Haibe. By now the Americans were beginning to apply the techniques originated by the leading Europeans, choosing the ideas they found most fruitful—straight-eights in particular—and seasoning them with Yankee practicality.

The events affecting the STD entries in the French Grand Prix on July 15, 1921 are of such complexity that only the explication of Sunbeam historian Anthony Heal will be up to the job:

“In mid-June Louis Coatalen returned from Indianapolis to find that work on the Grand Prix cars had not progressed as it should have done. The current coal strike was blamed for the delay. In the short time between the American race and the Grand Prix it was said that it was not possible to get the cars au point for racing, although the Duesenberg team, facing the same problem, had shipped their cars to Le Mans and were assiduously preparing them for the race.

“At 11:30 pm on Friday July 16th Louis Coatalen decided to withdraw the entire STD entry of seven cars. It was a terrible blow for all concerned in their preparation. Kenelm Lee Guinness and Henry Segrave, who were to drive the two Talbots, rushed from Paris to persuade Coatalen to change his decision, offering themselves to bear the expense of running their two cars in the race.

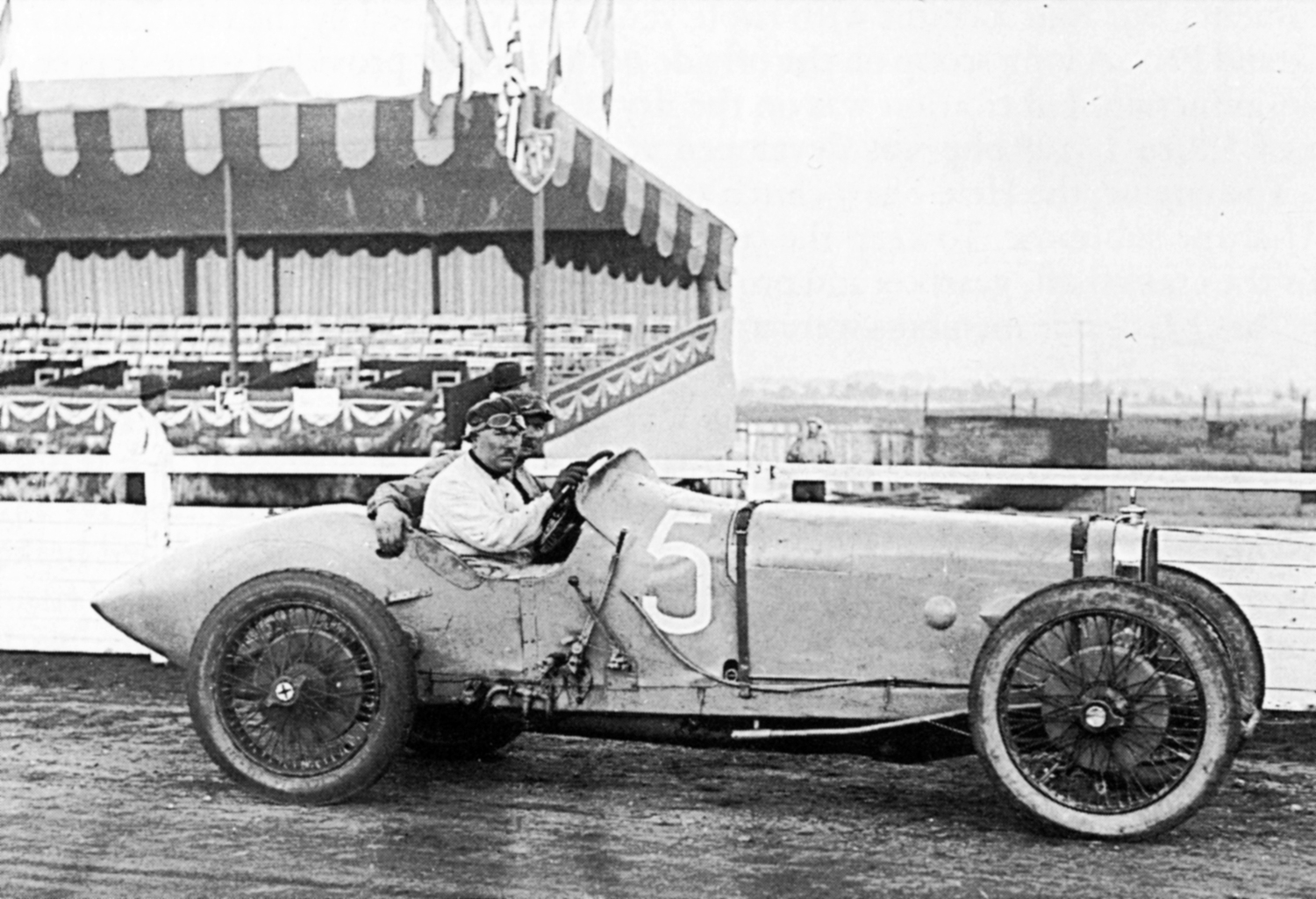

“René Thomas, who had been practicing at Le Mans, refused to take his Talbot-Darracq back to the factory. Coatalen relented and agreed that the two Talbots and two of the Talbot-Darracqs should be allowed to start but the two Sunbeams should be withdrawn. Thus, after a hectic week of day and night work, Guinness and Segrave brought their two green Talbots to the starting line at Le Mans and René Thomas with Andre Boillot presented the two blue Talbot-Darracqs.

“The cars were started in pairs at half-minute intervals. K. Lee Guinness and René Thomas left the line together but the Talbot soon forged ahead. Segrave was paired with Jimmy Murphy’s Duesenberg, the eventual winner, and Andre Boillot with Wagner’s Ballot. Ralph De Palma’s Ballot and Boyer’s Duesenberg put up equally fast times to lead the race at the end of the first lap. Guinness and Boillot were fifth and sixth while Segrave was in tenth place.

“René Thomas was already in trouble, having to stop at Pontlieue due to blockage of the petrol pipe. A couple of laps later he came into the pits to change plugs but the misfiring was found to be due to valves sticking. He was beset by a succession of troubles and he eventually retired on his 24th lap when a flying stone holed the oil tank.

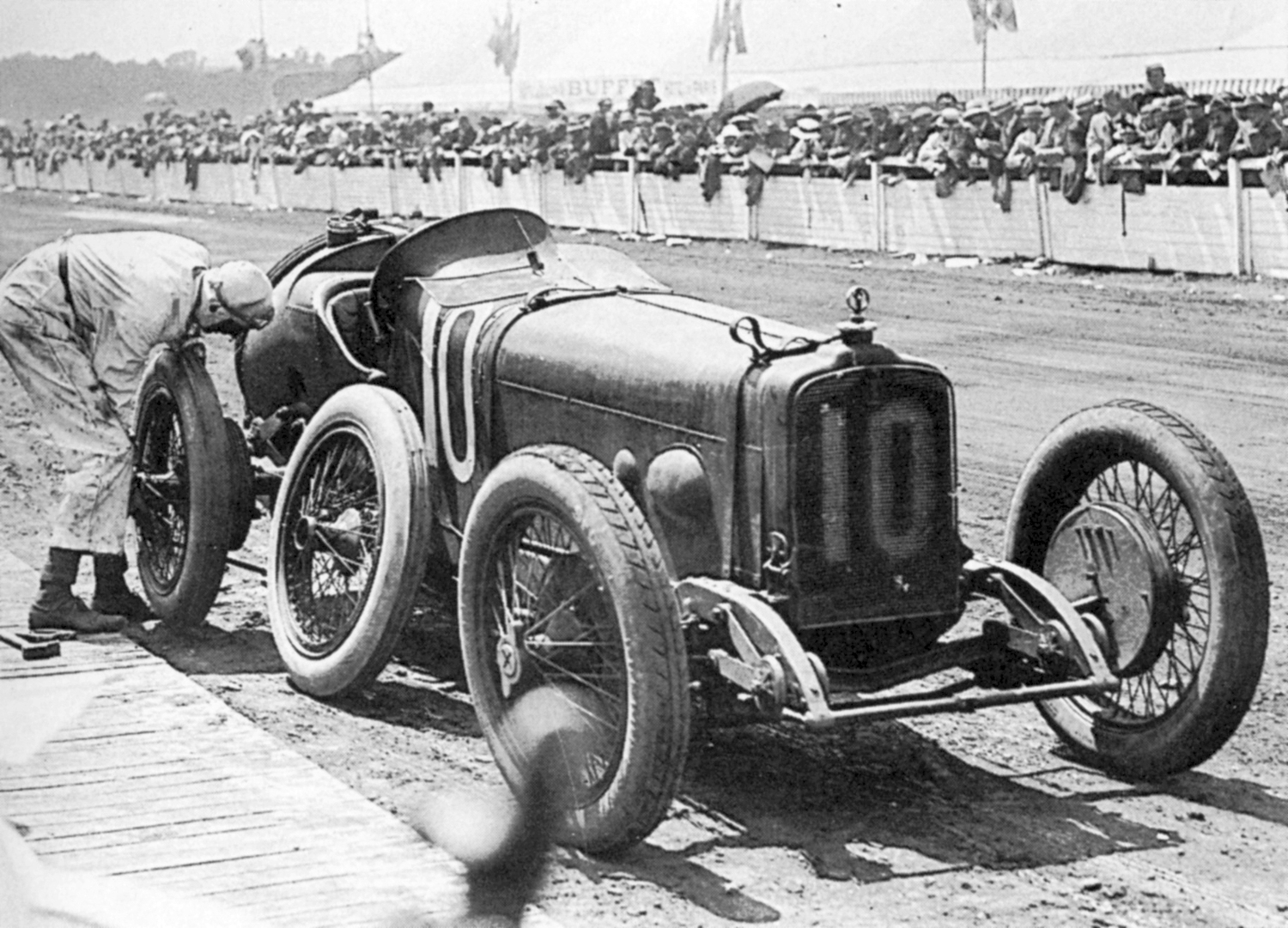

“The other Talbot-Darracq, driven by Andre Boillot, although not so fast as either the Duesenbergs or the three-liter Ballots, ran without any mechanical troubles, stopping only for fuel, oil, water and tires. His pit work was quick. On the eighth lap he changed a rear wheel in 35 seconds but he left the wheel and the jack on the road in front of the pit which drew a protest from the Duesenberg team in the next pit. Boillot had to change seven tires during the race. He was fifth on the second lap, eighth at half distance (15 laps) but sixth at 20 laps. He had gained a place by 25 laps and he finished in fifth place in 4 hours 35 minutes 47 seconds, having averaged 70 mph.

“K. Lee Guinness and Henry Segrave with the two Talbots were beset by tire trouble throughout the race. Guinness had to change nine tires and Segrave fourteen. K. L. G. had no starting handle so his car had to be restarted by pushing it backwards with reverse gear engaged. Because the engines were difficult to restart after a pit stop, they were kept running during tire changes.

“The late substitution of Zenith triple-venturi carburetors for the HC14 Claudel-Hobsons had left insufficient time to get the settings and adjustments right with the result that the drivers had to keep the engine speed over 2,000 rpm on the corners. This gave rise to a good deal of skidding, which exacerbated the tire problem. Segrave had to retime the ignition of his car by the roadside when a set-screw on the Delco distributor came loose.

“During the race the road surface became cut up and flying stones caused a great deal of trouble: Guinness had to whittle a wooden plug as the tap on the petrol filter had been broken off. Segrave’s mechanic, Moriceau, was knocked unconscious but he recovered and determined to continue in the race. In the early stages of the race a stone made a large hole in Segrave’s oil tank. Louis Coatalen thought it was beyond repair but Moriceau staunched the leak with a handful of cotton waste and caulked it by hammering in the tank side.

“Guinness held fifth place, ahead of his STD team mates, on the first lap but was then overtaken by both Boillot and Segrave. The latter was delayed by 14 tire changes and Guinness passed him on the 28th lap to finish eighth in 5 hours 6 minutes 43 seconds (nearly an hour behind the winner, Jimmy Murphy’s Duesenberg), having averaged 62.9 mph for 322 miles.

“Towards the end of the race Segrave’s car was firing only on six cylinders but he managed to finish ninth in 5 hours 8 minutes 6 seconds at 62.6 mph. After this very disappointing performance the STD entries for the Italian Grand Prix were withdrawn and the two Talbots were returned to the works at Wolverhampton to be rebuilt in the Sunbeam Racing Department.”

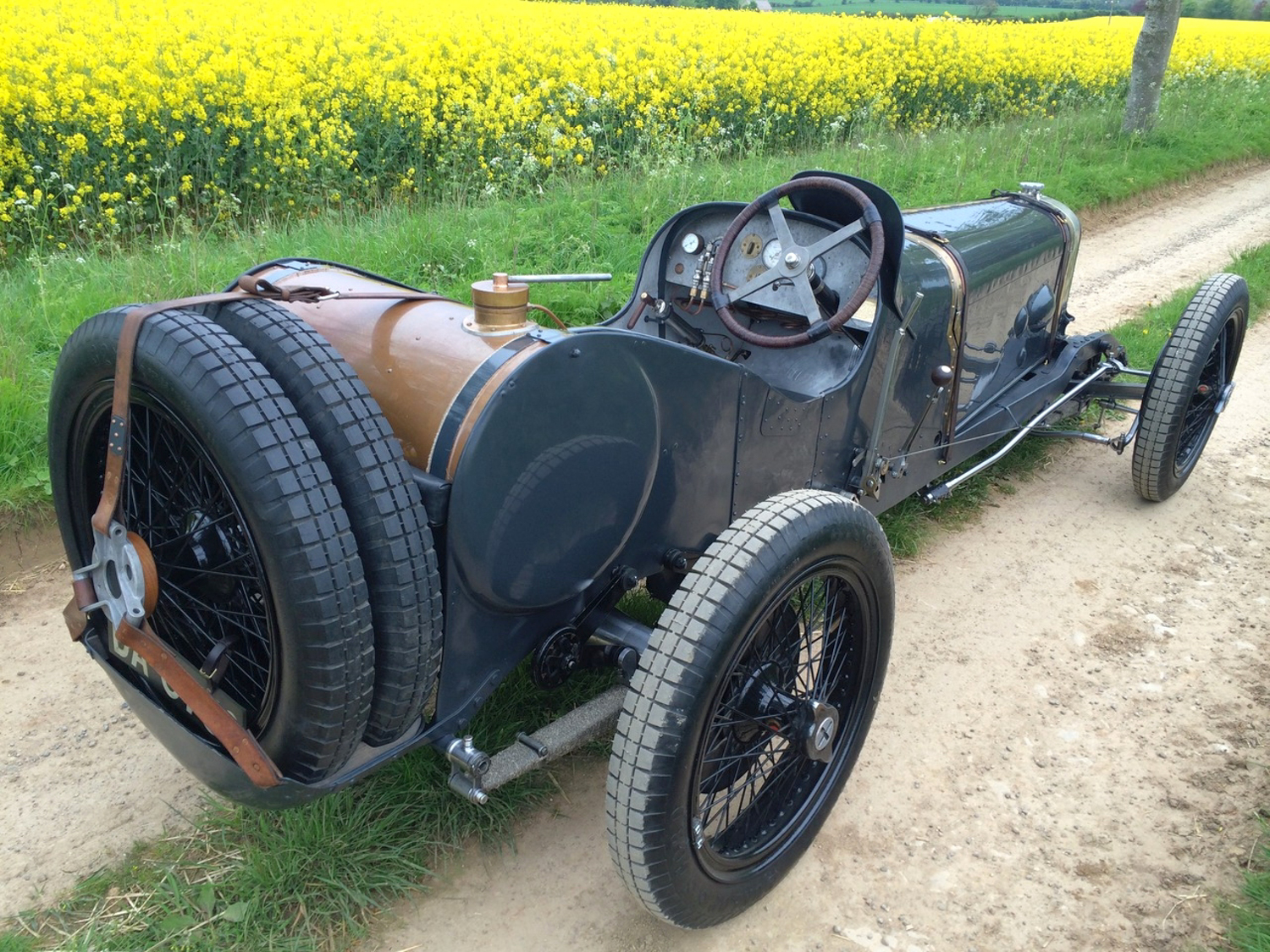

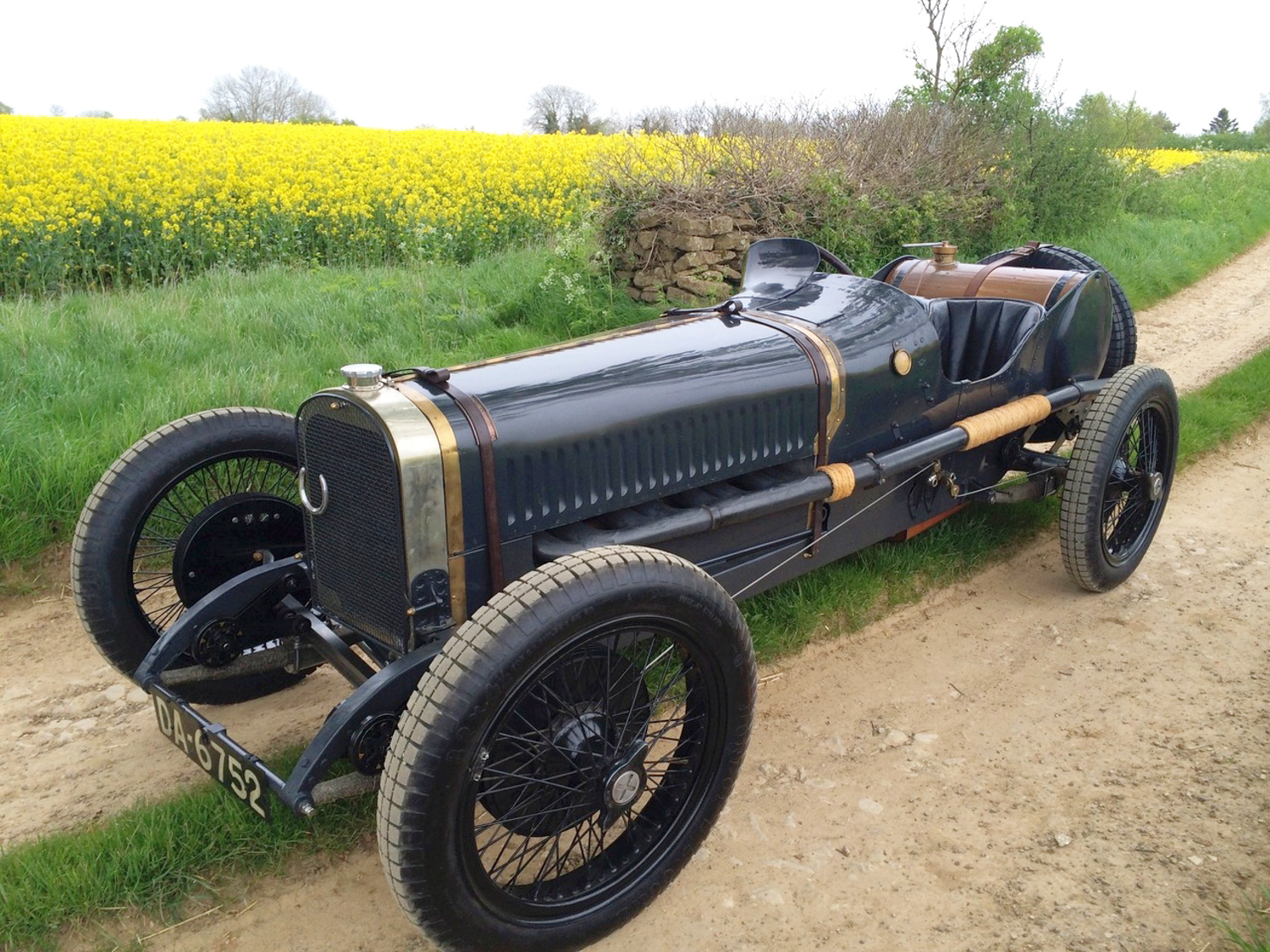

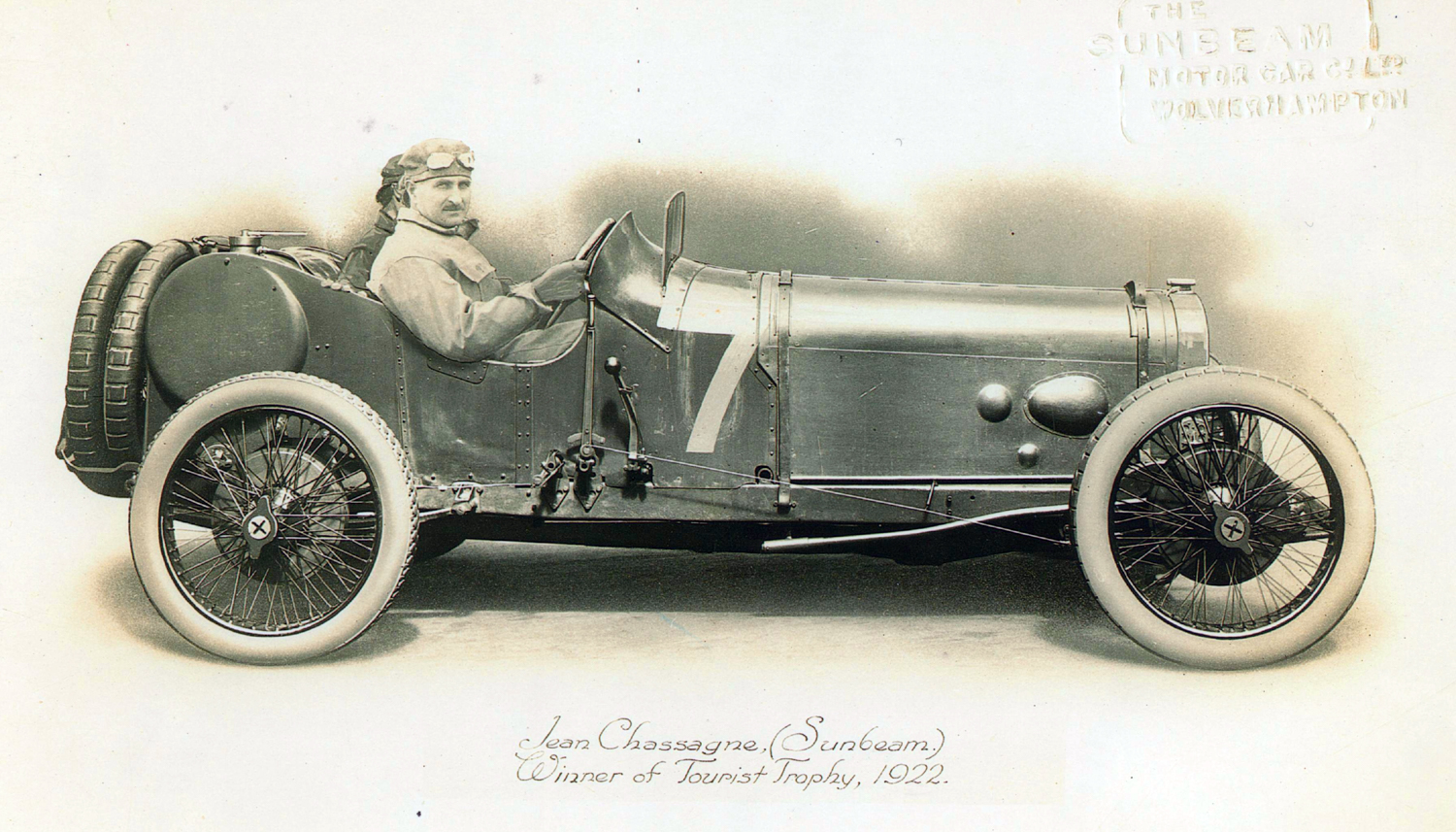

Although the premier racing formula changed to 2.0-litre cars in 1922, the Royal Automobile Club’s Tourist Trophy race on the Isle of Man was open to 1921’s 3.0-liter Grand Prix cars, so four of the STD machines were rebuilt to compete — three to race with one spare. Long tails were excised and replaced by bolster fuel tanks as used by Ballot at Indianapolis in 1919.

Attention to the engines saw a higher compression ratio of 5.7:1, Delco coil ignition replaced by two BTH magnetos and two carburetors chosen over four. Dynamometer testing showed the 520-pound straight-eights to be safe to 4,700 rpm and producing a maximum of 112 bhp.

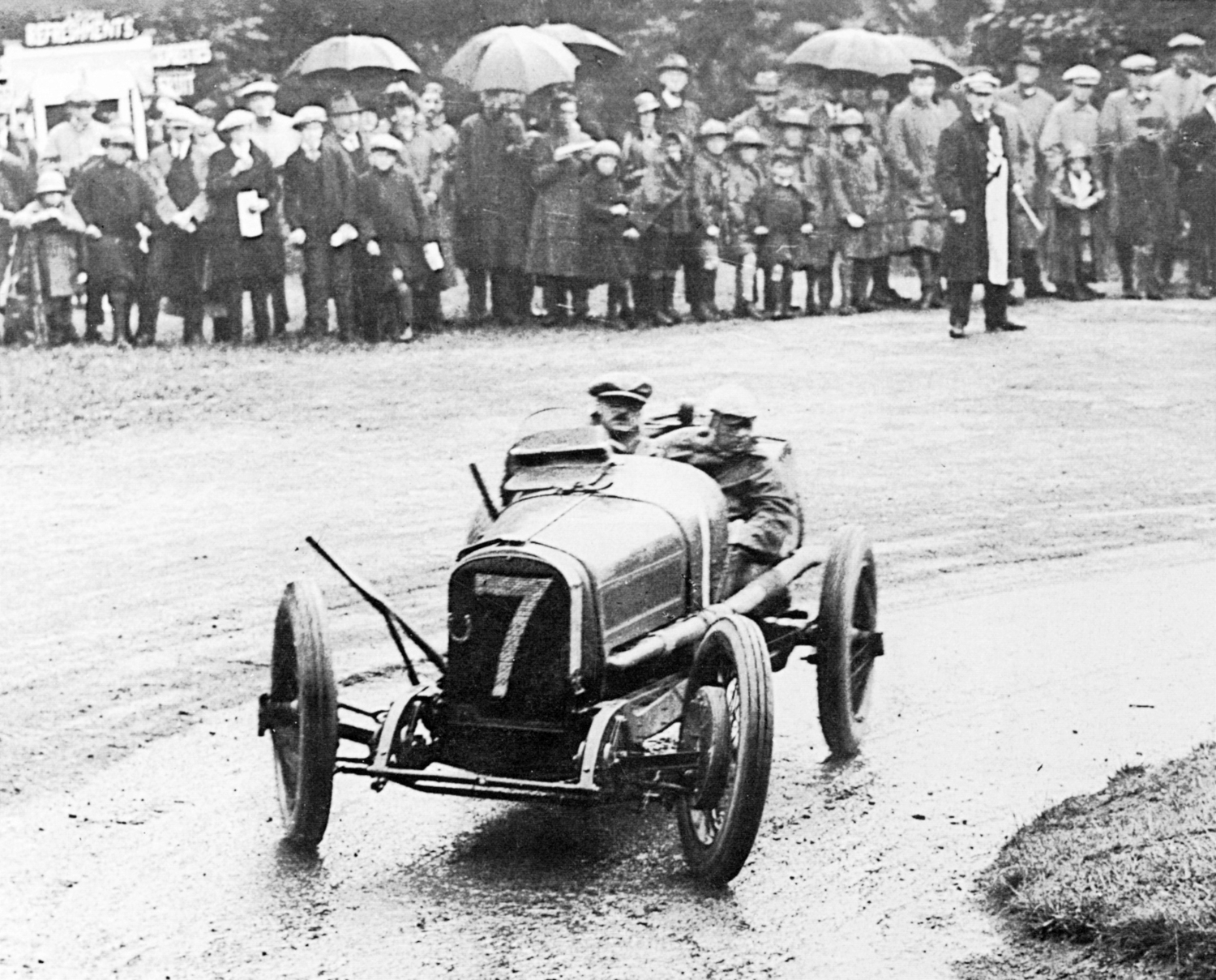

In the TT, on June 22, 1922, the Sunbeams — for they were all so designated — faced opposition from a team of new cars from Vauxhall and Walter Bentley’s new sporting models, both with 3.0-liter four-cylinder power. The Sunbeam strength was cut to two when Kenelm Lee Guinness’s car ran two big ends in practice and the spare engine’s clutch slipped so badly — a weak point of these cars — that the 1914 TT winner was unable to start.

Wearing a fender on the driver’s side to cope with a damp and windy day on the island, the two blue-grey Sunbeams soon headed the pack after the staggered start. Henry Segrave’s first lap was the race’s fastest at 57.3 mph, this low average an indication of the tortuous road circuit’s demands.

When Segrave had to retire with magneto trouble, Jean Chassagne, with a horseshoe wired to his radiator for good luck, took the lead in his sister car and held it to the finish of the five and a half hour race.

Successful in later races at Brooklands and elsewhere, these handsome eights were known known and respected in Britain as the “TT Sunbeams”.

By 1926, Sunbeam “No. 7” the 1922 TT-winning Chassagne car was racing in New Zealand, where it is recorded as finishing second in the New Zealand Motor Cup that year, raced by Matthew Wills. A later New Zealand owner of No. 7, Dick Messenger, fitted a sports-type body with hood and mudguards and used it as a 100 mph road car for years.

The Sunbeam was later acquired by Tom Wheatcroft of the Donington Collection who commissioned a full restoration to original specifications by Auto Restorations, in New Zealand. At the same time, a large stock of spares that came with the car was used to build a second car. At the Laguna Seca Historics in 1993, the restored original car was driven by former Formula One world champion Phil Hill.