Louis Delage may have been born to a humble assistant station master and his wife in Cognac, France, in 1874, but he rose to become a dominator of world motor sport. Yet he died in poverty, in 1947, at the age of 73, bankrupt, swamped by mountainous debts and destitute.

I don’t use the term world dominator lightly. Louis’ fabulous Albert Lory-designed Delage 15 S 8 won four of the five Grands Prix—at Montlhéry, Lasarte, Monza and Brooklands—to bring him the 1927 World Championship for Car Constructors, all four of them won by France’s highly talented and courageous Second World War Resistance fighter, Robert Benoist. It wasn’t so easy though, because the 15 S 8’s exhaust system ran along the right side of the cockpit and singed the drivers’ feet so badly that their shoes were often heard to sizzle in the pits after a stint as they plunged them into bowls of cold water!

Delage was born with only one eye, but that didn’t stop him from graduating from the Ecole des Arts e Metiers, at Angers in 1893, after which he moved to Paris to work for Peugeot, where he rose up through the ranks to become head of their test and research division. But Louis was determined to go out on his own, so he formed his company in 1905 to build luxury road cars and racers. It took 11 years, but his Delage Y won the 1914 Indianapolis 500 driven by Rene Thomas, while in 3rd came Albert Guyot in another Delage Y with, ironically, Arthur Deray’s works Peugeot jammed in between them in 2nd.

Louis’ earliest motor racing successes, from 1906 to 1908, were scored with Delage’s cars powered by de Dion 1- and 2-cylinder engines, but by 1909, 4-cylinder Ballots had taken over, after which Delage took the bull by the horns and designed his own horizontal-valve engines. Delage-powered Delages brought him 2nd place in the 1911 Coupe de l’Auto with a type Y driven by Paul Babiot, who later followed winner Georges Ballot’s Peugeot EX3 home in the 1913 Grand Prix of France at Amiens.

Delage enjoyed considerable early success on the roadcar front and, by 1912, he employed almost 400 people who built about 900 cars a year, all powered by low-output 4- and 6-cylinder, side-valve engines. That came to an abrupt halt with the outbreak of the First World War, during which the company produced munitions.

After the hostilities, Delage changed its policy and went in for big luxury car production, one of the first, his CO, was powered by a 4.6-liter engine that generated 20 hp.

As new roadcar production progressed, Louis went back to motor racing, in 1923, with his Tipo 2 12-cylinder, 2-liter LCV, which Rene Thomas retired from the year’s Grand Prix of France at the Tours circuit with mechanical woes. Better was to come in the 1925 French GP at Montlhéry though, with the two Delage LCVs taking 1st and 2nd places, driven by winners Robert Benoist/Albert Divo, who took almost nine hours to cover the race’s 620 miles, and Louis Wagner/Paul Torchy, with no fewer than five Bugatti T35s in their wake, which must have put Ettore’s nose out of joint!

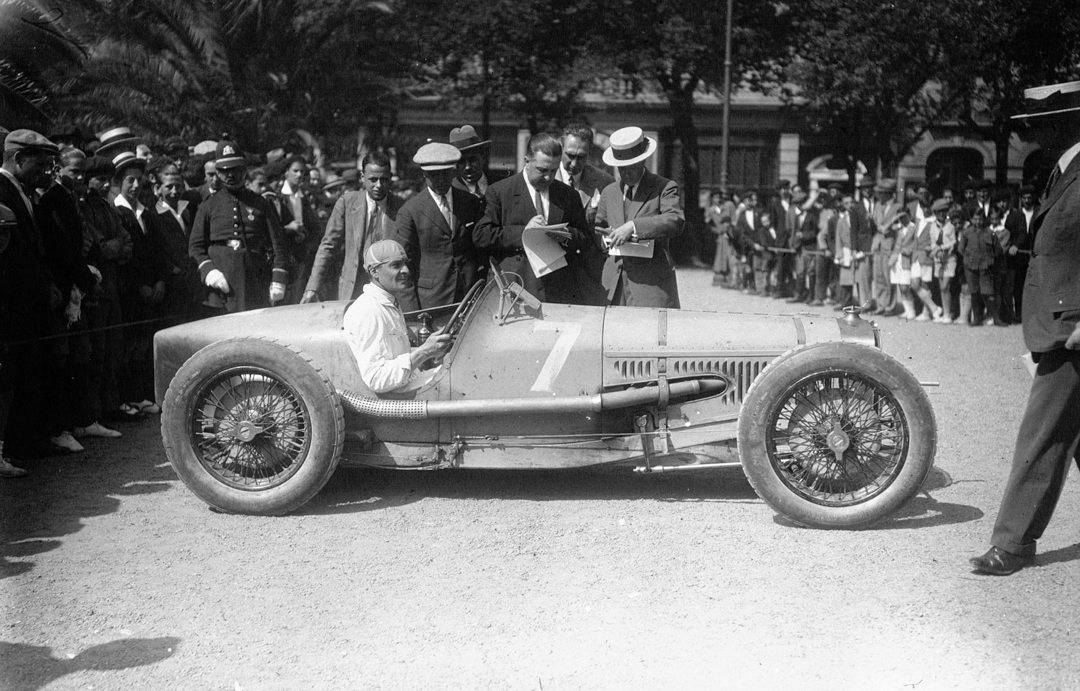

In 1926, Louis Delage built the car that was going to win him the world title. It was the Lory-designed 15 S 8, a slender, business-like looking racer with a 1466-cc, straight-eight, DOHC engine that had two valves per cylinder and a Roots supercharger. The car, which could quickly accelerate to a top speed of 170 mph at 8,000 rpm, immediately won in grand style by taking the first three places in that year’s French Grand Prix at Montlhéry, driven by Robert Benoist, Edward Bourlier and Andre Morel. That was the first of a stream of 15 S 8 1927 Grands Prix victories as it dominated the year’s constructors championship. In fact, the car was so overpowering that none of the opposition turned up at Monza for the Grand Prix of Europe, except for a couple of mild-mannered OMs from just down the road in Brescia. The grand finale was at Brooklands, where the Delages took the first three places driven by Benoist, Bourlier and Albert Divo.

But Louis Delage was already experiencing the financial problems that dogged him to the end. To begin with, he was forced to keep the number of 15 S 8s he built down to four. At the end of the season, with the 1927 world title in his pocket, Delage decided to race no more as his finances diminished, and that left Robert Benoist without a ride, so he was appointed manager of Banville Garage in Paris.

Two years later, Louis Chiron decided to drive one of the Delage 15 S 8s in the 1929 Indianapolis 500. He qualified the car 14th and worked his way up the field to finish 7th with an average speed of more than 87 mph. His was the only car among the finishers that was not based on Millers or Duesenbergs.

Dick Seaman had great success with the now 10-year-old Delage 15 S 8 in the voiturette class, but to keep up the car’s winning ways, he had the now London-based Giulio Rampone revise the Delage’s design in 1936 and, although the car disappointed the well-heeled young Seaman during the first half of the ’36 season, it suddenly turned good after more Rampone work. With it, Seaman won the Coppa Acerbo in Italy, the Grand Prix of Switzerland in Bern and, with a spectacular drive, the JCC 200 at Britain’s Donington circuit.

But that was it. Louis Delage owed money big time, his company went into liquidation and he became a bankrupt. And, in 1935, the rights to his brand name were put up for auction and sold to Delahaye. That company immediately fired Louis Delage and pensioned him off with a pittance. His life was made even worse by a divorce, after which he became a practicing Roman Catholic and died in poverty in December 1947, an all but forgotten man.