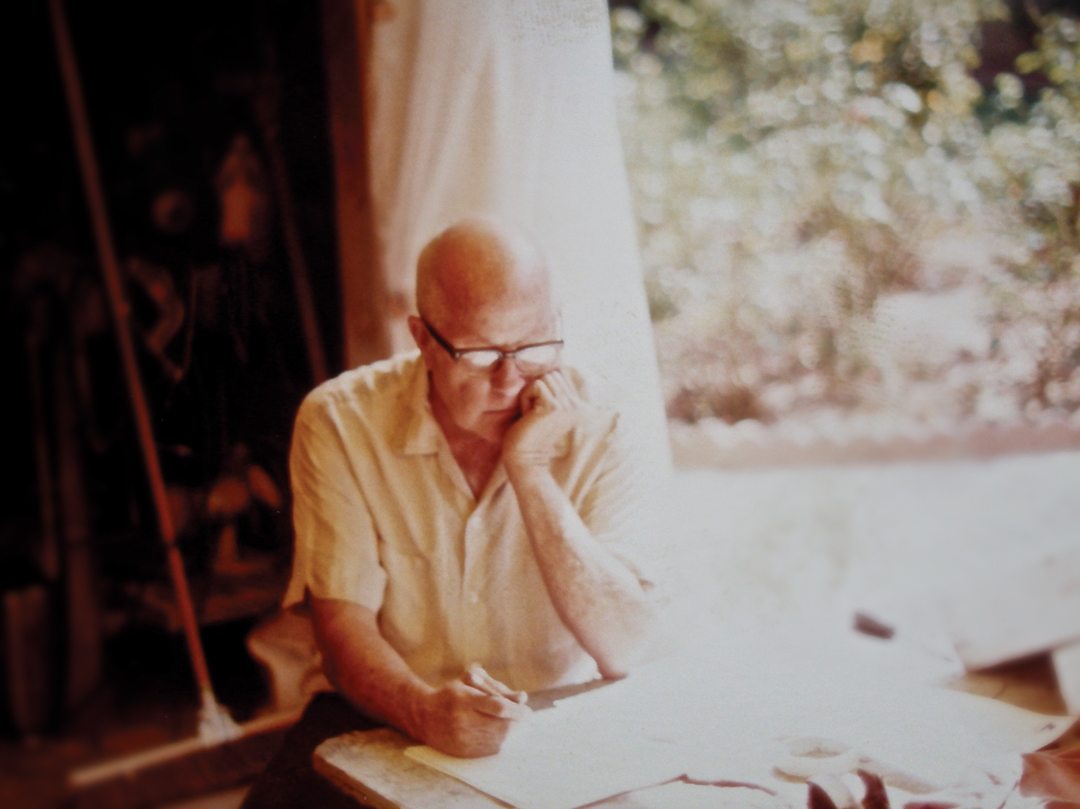

Bill Miller was a genius. You hear this term used a lot, but Bill was exactly that. He could paint like a renaissance master, was fully adept at technical drafting, had owned and operated a world class Southern California machine shop, and was known for solving mechanical problems that teams of engineers struggled to understand. He had substantial business acumen, owned a number of nightclubs in Los Angeles in the 1960s, and campaigned his own hand-built racecars to regional victory circles. With ample cash and discerning taste, Miller acquired several important vehicles over the years including two 12-cylinder Ferraris. But it was his creative spirit and intellectual prowess that led him to aspire to more than just owning sports cars. Bill was a risk taker, willing to gamble his money and eager to exercise his mastery of skills over a wide range of challenges. He wanted more than just a few sports cars; he wanted to build his own automobiles.

Smitten By Pegaso

Miller was particularly fascinated by the cars built by Pegaso. At the time, Ferrari was well-known for its sports cars, but Pegaso was new on the scene. Bill loved the twin-cam engine design, the exotic styling and the upstart mentality of Pegaso. These were cars intended for royalty, with prices to match. Bill became enchanted with the idea of owning one of his very own.

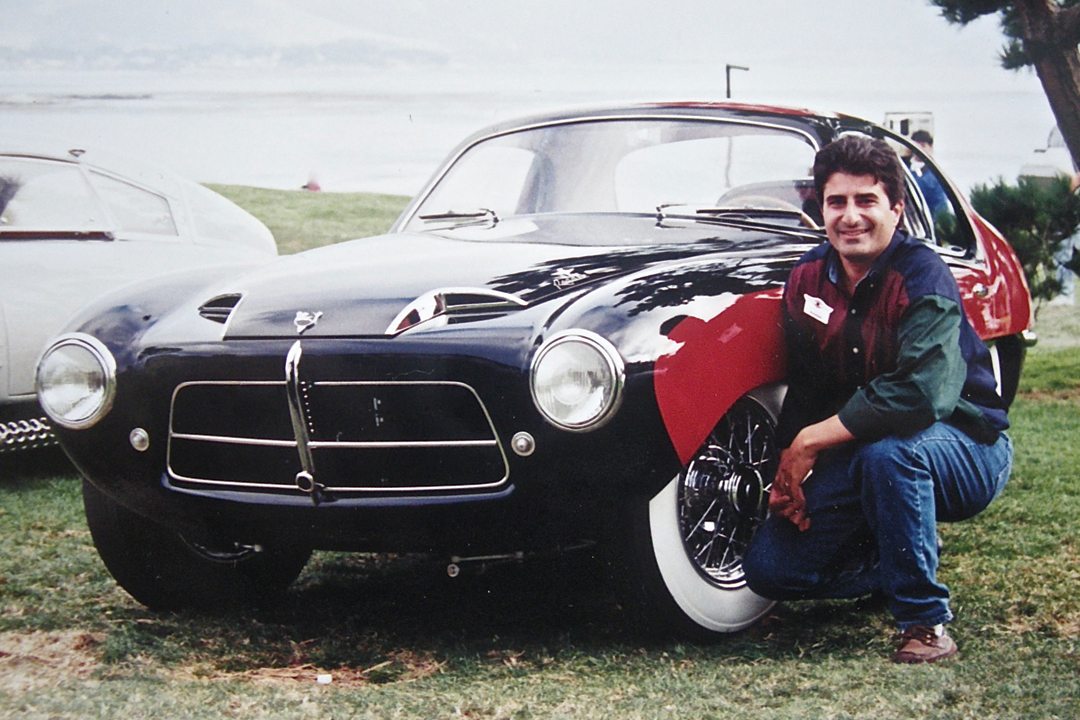

Not one to take a conventional path, Miller traveled to Spain in the mid-’50s and initiated discussions with Pegaso about a one-off car, built utilizing a Pegaso chassis and mechanicals. Miller and Pegaso executives contracted with Vignale to execute the coachwork, based on sketches of his own beautiful berlinetta design. Bill worked directly with Giovanni Michelotti fine-tuning renderings of the car. Final lofting of the design was completed in both convertible and coupe form, but the project suddenly halted when Pegaso’s financial support from the Spanish government came to an abrupt end. Knowing that his Pegaso Vignale was not to be, Bill turned his attention to capturing the next best thing, the stunning 1953 Pegaso Thrill, the Paris Auto Show car. So, in the late 1960s Bill, along with his Spanish wife Lupe, traveled again to Spain, this time to buy The Thrill. Once back in Southern California, Bill drove the car periodically, later treating it to a complete restoration between 1975 and 1977. The following year Bill decided to sell the car through the Los Angeles Christie’s auction. As fate would have it, before the auction my father and I were able to find Bill and the Pegaso. Standing in front of this awesome machine, we tried to persuade Bill to sell the car to us before the auction. No luck; Miller wanted to take his chances with the auction venue with a reserve of $48,000. Eagerly waiting in the front row, my father and I bought the Pegaso Thrill for $50,000. This is where my story with Bill Miller begins.

Miller Time

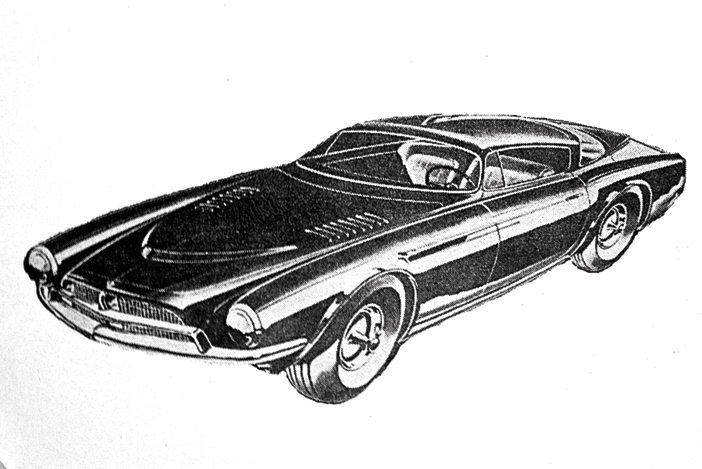

As a senior in high school I started sketching sports cars of my own design. When I met Bill following the purchase of his Pegaso, I was excited to share my drawings and hear him say, “Hey I’m thinking about building a car too.” That sentence led to a five-year collaboration on a car we called the Pegaso American, a mid-engine sports car answering the question: Had Pegaso stayed in business through the 1960s and early 1970s, what sort of car would it have built to compete in the early supercar wars?

We built the Pegaso American at Miller’s shop, which was never clean. There was always a story attached to each and every tool, chunk of wood and pile of scrap metal. Tools and parts littered Bill’s garage. Best of all, however, were the boxes filled with mountains of books, brochures, spare parts, emblems, trinkets from old car shows and all kinds of literature for review. Much of this material served as inspiration during the design and build of our Pegaso American. I would often set up in the studio section of Bill’s house and sketch new details for our project. Returning to the shop for Bill’s opinion, I would show a section or detail for the car and he would say something like, “I see you were looking at Abarth racecars. That looks like the front end.” Bill’s string of war, car and lady stories was endless. One story led to another, which often caused a new one to unfold. He also had a one-liner for every occasion. Some of my favorites included: “Problems are like tight corners on a race track, you gotta enter them slowly then come out hard on the throttle. Sometimes you have to GRUNT to loosen a bolt. Bolts aren’t the problem; it’s the nuts that get to you. There’s no mechanical problem that lunch won’t temporarily fix. Surround yourself with people who make you look lazy.”

Throughout the challenging but rewarding journey of the Pegaso American project I came to appreciate Miller’s extraordinary talents and dogged determination to build things of mechanical simplicity and beauty. Bill taught me a great deal along the way. Not just about automobiles but also about life, hard work and sticking to a “theme” in a project. Working on anything for five years, you get discouraged and motivated in peaks and valleys. Each day was something different. We would make a template, build the pattern, carve the details, cast the part, finish the part and put it aside until it was ready to become part of the car. I was always tempted to try different designs and often we would, but Bill would remind me to stay on course, craft the object with pride, and then move on to the next bit. We truly built the Pegaso American one piece at a time. Tempted as we were to use off-the-shelf parts for a lot of applications, we pushed each other to fabricate a better part, a nicer design, so that the whole car would be first class. In my work today as an automotive designer, I still maintain these ideas and methods building car parts, designing model cars and crafting beautiful objects.

The Miller V12

Miller was not one to talk a great deal about his past, but once in a while a good story popped out. One of my favorites began with my telling Bill how much I loved the 12-cylinder front-engine Ferraris. Bill replied, “Hey old buddy, I had two of them back when I owned night clubs. Those were the days, but you know Packard had 12-cylinder engines in their cars long before Ferrari. They just never built a sports car worthy of that engine.” Then Bill did what he often did so well…shock me. “I always thought Packard should have made a sports car…so I built one myself.”

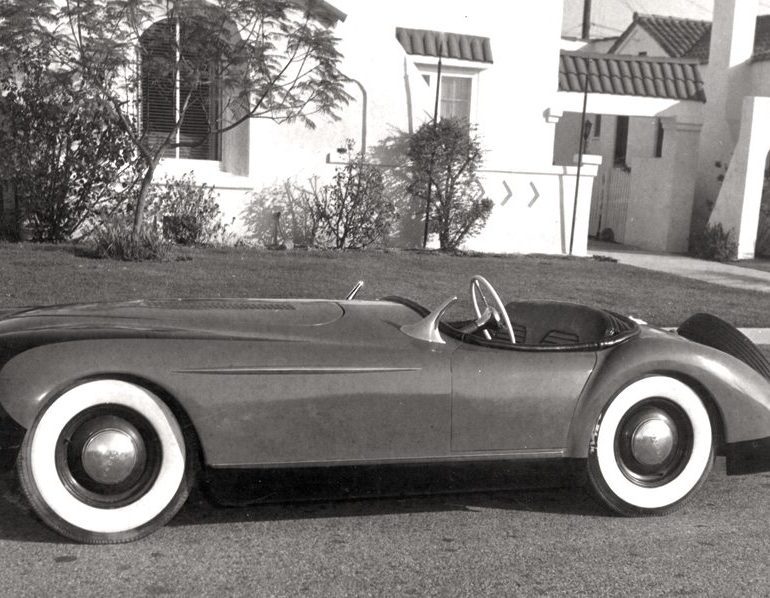

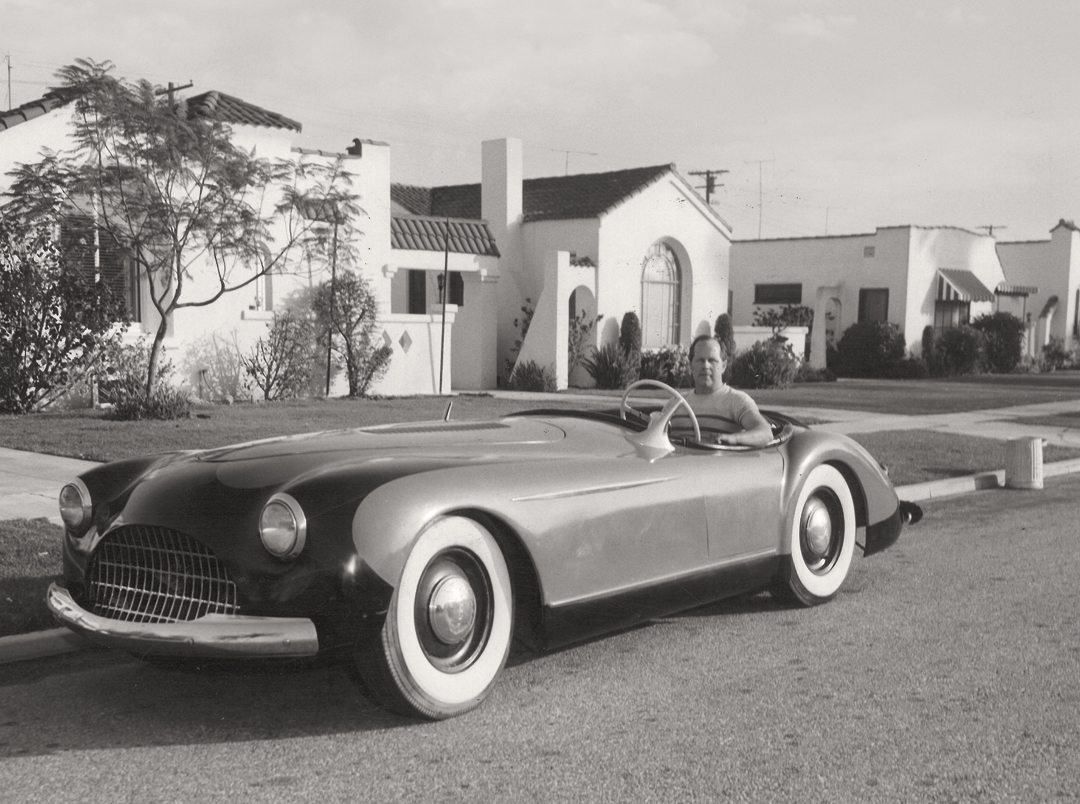

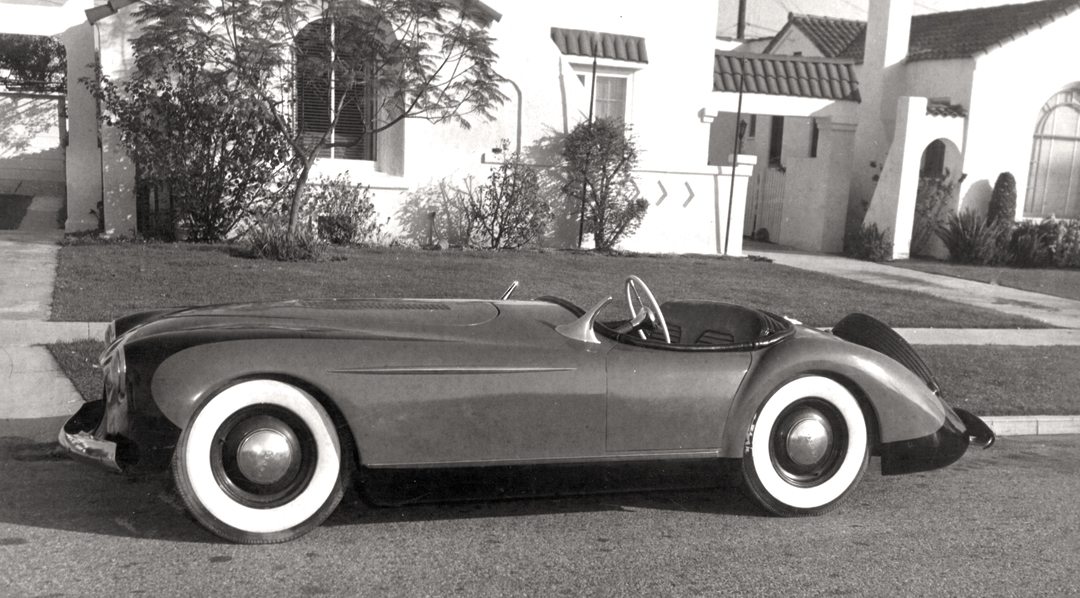

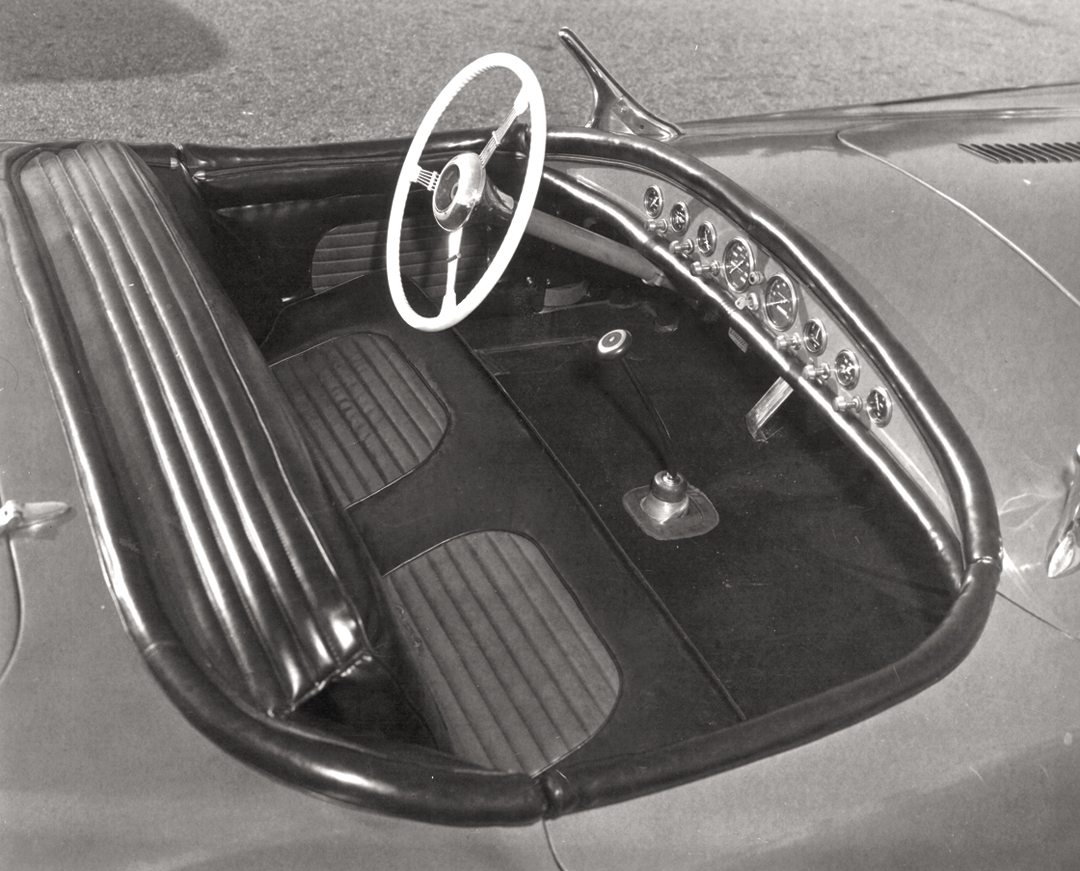

Bill pulled out a dusty photo album and handed it to me. Inside were astonishing images of his 1954 Miller Packard V12. Not grainy snapshots mind you, professional quality black and white 8×10 glossy photos taken for Road & Track magazine. Having never seen such a car, the list of questions popped out of me in a rush. What chassis? What engine? Huh? Twelve cylinders? Handmade metal body? How much horsepower? But most of all, I was astonished by the design. Low and lean and long in the hood, the car had an elegance and authority to it like no other car I had seen before. The hood reached out like a Jaguar 120, but had twice the power and a much wider stance. The driver position was far back and the short rear deck housed a spare tire, much like endurance racers of the ’50s. The two-tone paint scheme was wild and just a bit reminiscent of the Pegaso Thrill. The car embodied all the hallmarks of what Bill thought a great sports car should be.

To the best of my knowledge, the 1954 Miller Packard V12 is the only all-American, post-war 12-cylinder sports car ever built. Much of our sports car interests in the U.S. have been historically focused on the OHV V8 engine as a reliable and efficient package for performance. When Bill conceived the Miller Packard V12 in 1953, the modern V8 was still unproven as an icon of performance. Bill used the Packard partly out of American pride, but also because these V12 engines offered torque and performance beyond anything available in the U.S. The Miller Packard V12 pioneered an era of sports car performance and design that no other car builder dared to pursue.

By the time I met Miller in 1978, his fabulous Packard V12 was long gone. Bill advertised the car for sale in 1956, sold it, and from there it went missing. When Bill first told me about the car, I asked if he knew where it was and he was sad to report that he did not. Bill had built a racer or two as well in the ’60s, but never one to rest on his laurels, those too were also sold to finance new ventures. But Bill never forgot and always missed his Packard V12 sports car. From time to time we would talk about this car and what it had meant to him. Building and then driving that dream was a source of pride for Bill. It not only showed others what he could do, it was a statement of American pride and performance.

Knowing Bill loved that Packard so much, I engaged several of my friends in the car collector world to search for the car. No one had ever seen it, let alone knew where it might be hiding. It was one dead end after another. In the years that followed, I went to work for a wide range of companies as a designer, and along the way bought and restored many cars. As an aside, in 1993 I re-restored the 1953 Pegaso Thrill and showed it at Pebble Beach in 1994, winning Best-in-Class in the Touring Coachbuilt Class. Despite my experience and connections in the car hobby, however, I could never find the Miller Packard V12; in fact, I never heard a whisper about it.

Noted American automobile collector Wayne Graefen had been surfing the web and stumbled onto a site with a recent photo of an intriguing car. It was not a car he knew, but he was instantly captivated by its very form. Several phone calls later Graefen had found the Miller Packard V12. Best yet, the car was available for purchase. After much internal debate Graefen decided to pass on the car and at that point he gave the information to my friend who immediately contacted me with the news. It may sound trite, but I was overcome with emotions. All the years working alongside Bill came together in this news. His engineering and building skills, his passionate ideas, his legacy would be known.

I quickly called the owner, Greg Garcia, a truly wonderful fellow. Greg revealed a great deal about what had happened to the car in the years after Bill had sold it and the many years it had sat in storage. To the best of my knowledge, the chain of events and ownership are as follows. Miller sold the car to the Aadlen Bros. in 1956. It appears that Bennie E. Yocum had acquired the Miller Packard V12 in 1962 and had it in storage as part of his collection until his death in 1993. From there the car passed to his wife, Mary Jane Yocum, who sold the car to Collector’s Cars Sales Co. in 1996. From there the car passed through a few business entities until it was acquired by Greg Garcia and some business associates in 2000. At some point, Garcia wound up as the sole owner of the Miller Packard V12 and has cared for it in dry storage ever since.

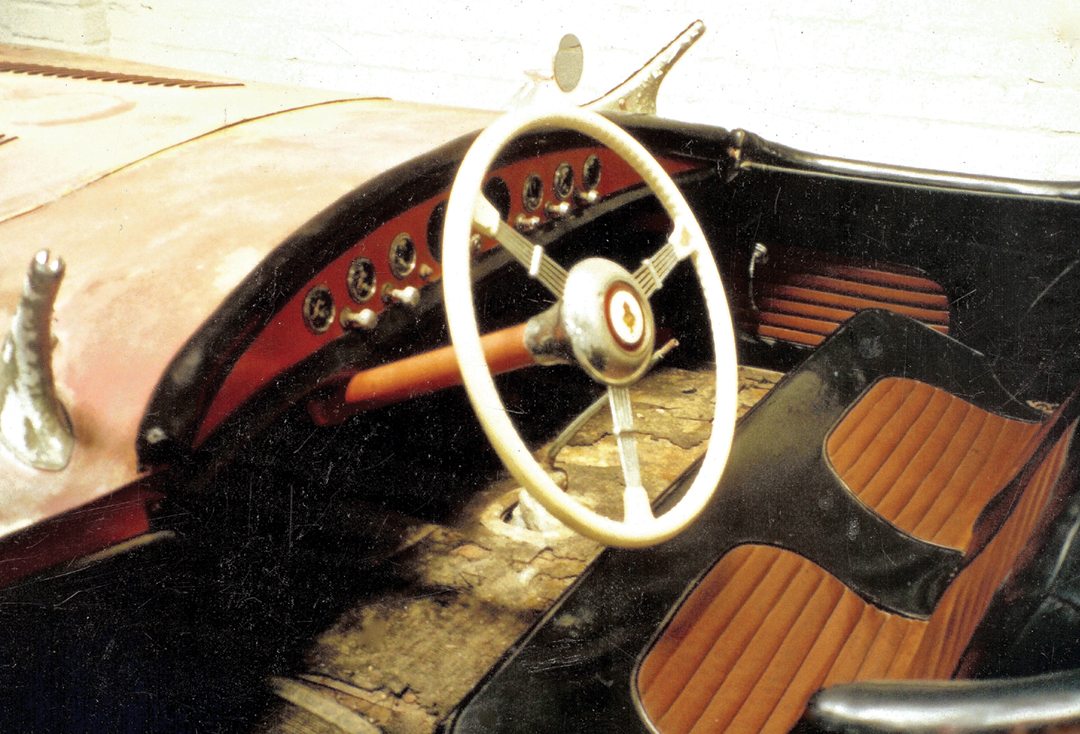

My friend loved the car, but allowed me to have the first crack at it. From photos and a thorough description provided by Garcia, it was clear that the car was all there but was in need of a total restoration. Some of the details had been slightly altered, but it was absolutely Miller’s beloved machine complete with the original chassis, engine, transmission, major body components and interior. Garcia had been in the midst of a complete restoration, but had run out of steam. He was therefore willing to sell the car. Although I would have loved to bring Bill Miller’s iconic one-off back to life, I decided to pass. When I called my friend back, he wasted little time buying the Miller Packard V12. His plan is to restore the car and debut it at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance.

Bill Miller passed away more than a decade before his Packard V12 sports car was unearthed. Had he been around to see this chapter in his life story unfold, I am certain he would have been overjoyed. I am equally certain that he would have been inspired to offer up another one of his famous Millerisms; “If a man built it, another man can fix it.” Rest in peace my friend, your spectacular machine is in capable hands and is on its way back to life.