1968 Fiat-Abarth 1000 TCR

Variations on a theme – that’s the one-liner which always comes to mind when encountering an Abarth creation, especially one of the many, many machines which encompassed humble Fiat origins with Abarth genius. But the theme was more a concerto or an opera, so many stories were told and tunes played. If Carlo Abarth had been a composer, he would have been a Verdi or Puccini, or perhaps Mozart, as he did indeed come from Austrian heritage. Even that may be unfair as Abarth’s international connections were farther reaching. In addition to the many Italian companies with whom he worked – manufacturers like Alfa Romeo, Fiat, and Lancia as well as coach builders such as Ghia, Vignale, Zagato, Viotti, Sibona and Basano, Allemano, Bertone, Boano, Ellena and Pininfarina – he also had significant enterprises with the German Porsche and the French Simca and Renault companies.

Carlo Abarth’s influence and market penetration were as impressive as his cars. His entry onto the American scene in the 1950s ensured a lasting home for many of the various Abarths which he produced, especially his superb 750 Fiat Abarth Zagato “double-bubble” coupe. The American “blessing” had been bestowed upon Abarth products as early as 1953, when the somewhat unlikely September issue of Hot Rod Magazine reported in effusive terms about the futuristic 1500 Biposto Abarth, which featured a Bertone body and a tuned 1400 cc Fiat engine. This car had been bought by Packard after doing the rounds of the European shows in 1952 and was being studied by the American company’s engineers. Packard did go on to design some pretty zany looking machines, though they always remained about four times the size of anything from Abarth!

In many ways, the 1000 TCR – the musical variation we are going to play for you on these pages – is from Abarth’s later “saloon period.” This was a point in Carlo Abarth’s career when he was making rapid technical advances and was trying endless approaches to solve the problems of winning in rallies, sprint, endurance races and hillclimbs, as well as in the accessory sales market. For many, the 1000 TCR is an end-point in small saloon development.

1000 TCR in Context

Shortly after World War II, Carlo Abarth and a talented German engineer, Rudolf Hruska, (who was later to go on to important things at Alfa Romeo) were introduced to the Cisitalia manufacturer, Piero Dusio, and went to work on improving the design and production of the Cisitalia. Dusio already had in his employ Dante Giacosa whose own baby was the Fiat Topolino, and later, Ferdinand Porsche would join this illustrious though relatively little known group. Dusio was ambitious and built formula and sports cars and even had Porsche design a Cisitalia Grand Prix car, which essentially drove the company into bankruptcy.

Abarth and Hruska had produced and raced the Cisitalia 1100-cc sports car in 1948 and 1949 under Abarth’s control. When the company went to the wall in 1949, Abarth raised the funding to set up his own shop in Turin’s Via Trecate in June of that year. Abarth purchased three complete Cisitalia spiders, three spider chassis, and a D46 single-seater. With a glowing endorsement from famed Italian driving legend Tazio Nuvolari, Squadra Carlo Abarth was born. Borrowing Cisitalia’s numbering scheme, Abarth’s first seven cars were known as 204 Abarth-Cisitalias. The first so-called “pure” Abarths appeared in 1951 as the 205 series, though their heritage remains somewhat cloudy. This new car disposed of the ladder frame chassis of the earlier Cisitalia and used steel box-channel sections with a steel floor pan.

Carlo Abarth had intended that his new business would produce and market accessories for the car industry, particularly for racecars, and though production of actual cars had occurred to him, it was not to be his main business. However, as he developed the accessory business, he needed to keep alive the possibility of automobile manufacture, so he accomplished this by producing a number of special cars for the main shows of the period in conjunction with the best of the current chassis and body builders of the time. Thus, the early 1950s saw the 1500 Bertone Biposto already mentioned, the 1952-53 Abarth-Fiat Ghia, the 1954 Abarth Simca GT, the 1954 Abarth Alfa Romeo Ghia and the Abarth Renault Frigate Boano of the same year.

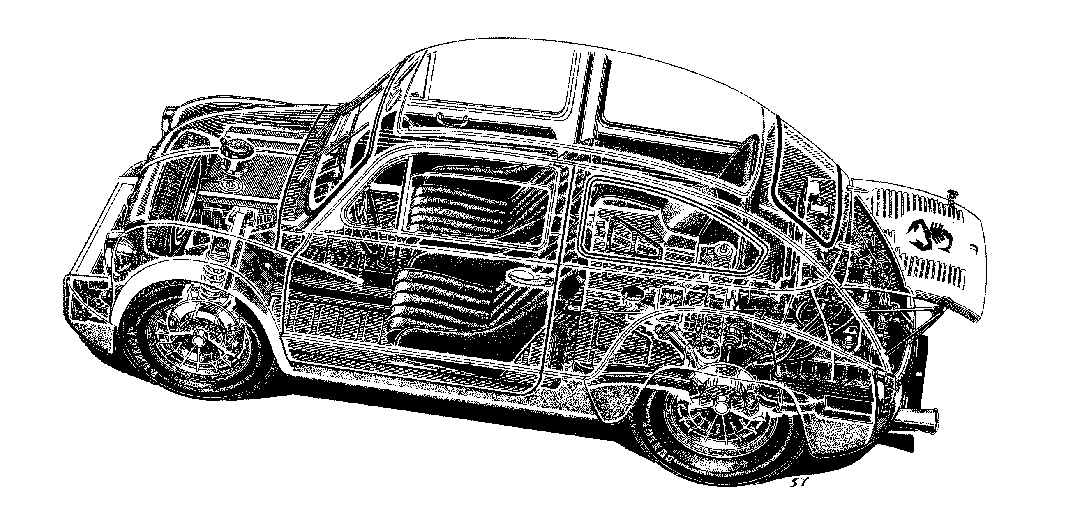

In 1955, the Fiat 600 appeared for the first time at the Geneva Motor Show, a European motor show recognized then and today for the debut of very important and enduring automobiles. In spite of the variety of Abarth products which appeared over the years, the Fiat 600 was to become the most significant baseline machine of Carlo Abarth’s entire career. As author Pete Vack points out about Giacosa’s Fiat 633 cc successor to his pre-war Topolino engine, this engine with three main bearings had the “water-cooled power-plant perched aft of the independently coil-sprung rear wheels and mated to a sturdy four-speed transmission. This was attached to a steel unitized body, which was the rage in Europe but rare in America. Front suspension consisted of a transverse leaf spring and upper wishbone, controlled by telescopic shock absorbers. The package weighed in at around 1700 lb. wet and was Italy’s answer to the Renault 4CV and the popular Volkswagen.”

The Abarth versions of the 600 were at first fairly modest. The pattern was to lay down a set of general specifications for a model for three or four years, refine and develop it during that period, but stick to the basic specifications. Thus, the 1956-59 Fiat Abarth 750 Series Berlina featured a kit with increased bore and stroke to the original 633 cc unit, bringing it up to 747 cc with high-compression pistons yielding a ratio of 9:1. Additionally, the Abarth radiator was bigger, the final drive was changed, and Abarth headers and exhaust were used. The Abarth exhaust system gained worldwide fame, not only because it was technically efficient, but also because Abarth was excellent at marketing. In the USA, everyone with a “foreign” car wanted one. There were also Abarth additions to wheels and body trim as well. The famous Abarth hallmark of the raised rear-engine cover appeared in 1959 to aid cooling and aerodynamics.

The first of the TC cars came along in 1960, in Abarth’s second series of cars. This was the 1960-61 Fiat-Abarth 850 Berlina TC Series I, which would be followed by the 1962-64 850 TC Nürburgring, the 1962-64 1000 TC, the 1964-68 1000 Corsa, and finally, the 1966-70 1000 TCR.

Chassis improvements were necessary for the 850 TC, including Girling disc brakes at the front, better magnesium wheels and the relocation of several components for better weight balance. Incidentally, there were numerous arguments at the time and since about the meaning of “TC” as some thought it meant twin-cam, when in fact it stood for Turisimo Competitizione as Abarth’s racing ambitions were becoming more evident. The Nürburgring version of the 850 TC was the same car with five more bhp due to a revised camshaft, and named after the TC scored a now famous win at the German track in 1961. The Nürburgring version also featured a five-speed gearbox and a top-speed just a hair under 100 mph.

In an attempt to compete with the Mini-Coopers which had begun to challenge and beat the Italian cars in the Under 1000 cc classes, Abarth soon took the old 600 block even further by increasing the bore and stroke to 65 x 74 mm, achieving a displacement of 982 cc. This produced more usable torque than the 850. While other Italian firms such as Giannini and Siata were doing similar things, the Abarth operation had grown much bigger and was dominating the tuning scene. The 1000 TC had 60-66 bhp and could manage 0-60 mph in 12.2 seconds. Compression was measured at 9.8:1. The later 600D block and an AH built 600 block were also used in this model with variations in placement of radiators and type, size and location of oil coolers. The customer could buy the kit for his own basic car or the whole machine by this time and could order either a street version or further modified race version.

By 1964, Abarth decided to homologate a number of options onto a racing version of the 1000 cc car, and this became known as the 1000 Corsa, essentially a pure racecar, though some of these were used as road cars. One of the problems of determining the authenticity of an Abarth Corsa is to discover whether it was built as a racing Corsa and whether it retains the factory options. This is not always an easy task.

The 1000 Corsa had a five-speed gearbox, 74 to 80 bhp, four wheel disc brakes, modifications to the front and rear suspension, and even larger front radiators integrated into a bumper of sorts. It is also important to note that the 1000 Corsas could be supplied with the smaller engines to contest other classes.

R for Radiale

The term “Radiale” has been a source of confusion for many as the term is often used in connection with aircraft engines. Recently, I visited Le Musee De L’Automobiliste, in the south of France, which has on display the rolling chassis of an Autoguido….a mid-engine racecar with a “genuine” aircraft type radial engine. This is, however, not what Abarth produced.

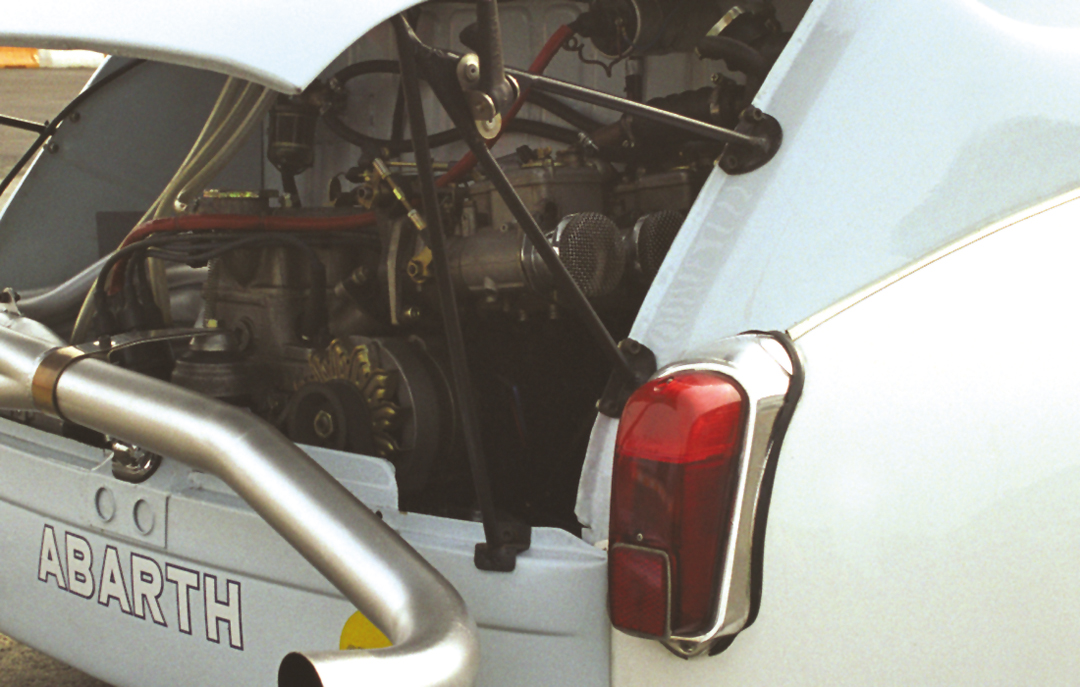

By 1966, the original Fiat 600 block and head had been stretched about as far as it could go, so Abarth created essentially a miniature version of Chrysler’s Hemi, using hemispherical combustion chambers in an all new head that retained the in-block cam and pushrods and breathed through twin Weber 40 DCOE sidedraft carburetors.

This version appeared at a time that coincided with new European Group 5 regulations, and so with some 108 to 112 bhp at 8400 rpm, the 1000 TCR (the “R” now signifying radial or hemispherical head) was hugely successful as it also now had advanced coil-over shock absorbers and parallel front wishbones and rear tubular swing arms. With 13 x 6 wheels, this was a proper racecar… rather a long way from what Giacosa had originally designed 15 years earlier.

Driving the Fiat-Abarth 1000 TCR

As long as I have been an avid fan of very small cars, and especially Abarths, I have never had the chance to sample what is really the epitome of the Fiat 600’s development, so when an enthusiastic group of Italian classic Abarth owners and competitors offered a day of hard driving at the half-mile Circuito Attilio Mercadante – a karting and test track not far from Turin – it was not a chance to be missed.

Domenico Fasano runs one of those little Italian treasure troves you find down tiny back streets in Italian cities, a garage that repairs, restores, rebuilds and races classic Italian machinery. Amongst his part-time employees are the Baldi brothers, who with Domenico were all original Abarth employees and went to Fiat when Fiat took over the Abarth business. Giovanni and Elio still work some of the time in Fiat Research and Development but spend the rest of their time with Domenico working on their own and customer’s historic race and rally cars.

Domenico’s 1000 TCR is to 1968 specs with the standard two part chassis identification: 2336840/1731. The first set of numbers refers to the Fiat chassis/body and the four figure number is Abarth’s own identification. The car sits in a squat position on Dunlop Racing Tires, 135/545 x 13 on the front and 175/550 x 13 on the rear. It is a beast!

Domenico found the car in France needing a full restoration, but it was complete, something of a rarity with these cars, so he was able to fairly easily restore it to its 1968 specification. It had a race and rally career with Rein Alexander Zwolsman who bought the car new in April 1968 and was a reasonably successful driver in the late 1960s. The car competed in some European Touring Car events, and at this stage its history, is being investigated in more detail. The owner was so happy to find an authentic car with its original components, he was less worried about its racing provenance as virtually every 1000 TCR was a racing car at some point in its career.

As in all Abarths of this type and period, the steering wheel is on the left with a neat gate-protected five-speed gearbox to the driver’s right. It is as impressive a little car on the inside as it is spectacular looking on the outside with big exhaust, raised rear lid, large front-mounted radiator and an overall appearance of a racecar that is going to steer from the back! Inside, it’s all business. First gear is back and to the left, and the rest is the standard H-pattern with reverse forward and left and locked out by a sprung gate… as to avoid expensive mistakes! This car carries two rev counters for reasons my fairly limited Italian prevents me from discovering. One tach revving to 10,000 rpm, the other to 8,000 which I was to use up to a self-imposed limit of 7,500. The Speedo reads to 160 kph, and there are the standard temperature and pressure gauges, on/off switch, and that’s it…all simple, basic and functional. The full roll cage helps to stiffen the body/chassis, but as the car is so diminutive it feels as if the cage is all around you!

With a close ratio gearbox for current hillclimb use, 7,000 rpm is reached very soon after the tiny engine barks into life and disappears down the track. Caution is clearly necessary for this wary driver though I am later told to rev away. “It can take it!” encourages the car’s owner. In fact, one of the cars I drove that day had the rev counter taped over so I wouldn’t be distracted…but that’s another story!

The third gear torque amazed me in this car as did the relative neutrality of the handling under duress. I say “relative” in that the tail hangs out all the time but is totally manageable with a sensitive right foot. Because of the tightness of the circuit and the low ratios, mostly second and third gears with one shot at fourth were used, but it was a quick move from second to third to keep usable revs. Essentially, what you are driving here is an engine with a stick! The tires are helpful but everything else is a blur, as you wind up to maximum revs in seconds, fling it into the next corner, occasionally making use of extremely effective all-round disc brakes and sliding out on to the next straight bit, keeping the revs as high as possible. Unfortunately, I never got to try hand brake turns…it just wasn’t necessary as everything is absolutely controllable with the accelerator.

The big Weber carbs fluff a bit on the over-run which I put down to learning just how much throttle is necessary as you adapt to using the engine braking in corners and minimize the use of the middle pedal. What I began to wish for was a long straight to see what top end felt like, but that wasn’t going to be possible here. Handling is very sensitive, even under braking and hard acceleration, but again, it all feels like you are in charge. The wrists get a good work out but you don’t have to put vast amounts of muscle into driving a 1000 TCR… the TCR rewards subtlety.

Using the curbing on this circuit tended to provoke more dramatic oversteer, so if you come into a chicane fast on the brakes, there is initial understeer which turns rapidly to oversteer as you apply throttle with one side of the car slightly raised. You develop quick reflexes as a result, but it is all part of the challenge …..and the immense fun of this car. Please Domenico, how about trying Monza and then the Nürburgring!?

Buying and owning a 1000 TCR

Unlike many of the cars in the series of which the TCR was the last, this car is really not a street car, so if you are after one, you really have to hunt in the used racing car columns. It must be said that Abarths and Fiat-Abarths of most types have been and are being faked. The reason for this is simple: Abarth sold complete cars but he also sold cars which the public could modify with Abarth accessories. Cars built at the factory traditionally have the dual numbering system, but this is not fool-proof as sometimes the Abarth badge was removed, and it was easy enough to fit one on a car which was not a factory machine. If you want a real racing Abarth, you need to learn the system and consult the experts, of which there are enough, so no excuses if you don’t. While the original records were not kept in a meaningful fashion, there are now people who have researched this area very carefully for your benefit.

On the maintenance front, Abarth parts may tend to be expensive, but the cars are easy to work on, easy to take to pieces, and easy to put back together. All told, this encourages getting them into, and keeping them in, prime condition. As we said, the 1000 TCR is a racecar, so on-going maintenance depends on how hard and how often you race. There are the slightly lesser street versions if that’s too much for you, and you can have just as much enjoyment.

Specifications

Body: Steel, unibody

Weight: 583 kg

Suspension: Front: Coil-over shocks and parallel wishbones. Rear: Tubular swing arms

Engine type: In-line, 4-cylinder Radiale, with hemispherical combustion chambers

Engine capacity: 982-cc

Bore and stroke: 65 x 74 mm

Power: 108 bhp

Valves per cylinder: 2

Carburetor: 2 Weber 40 DCOE side-draft

Fuel pump: Electric

Brakes: Hydraulic 4-wheel discs with Girling 3-piston calipers

Disc diameter: 236.5 cm x 9.65 cm

Tires: Front: 135/545 x 13 Dunlop Racing. Rear: 175/550 x 13 Dunlop Racing

Resources

Clarke, R.E (Editor)

Abarth Gold Portfolio 1950-1971 1992 Surrey, England

ISBN-1-85520-200X

Vack, P.

Illustrated Abarth Buyer’s Guide 1991 Motorbooks International, Wisconsin,USA

ISBN-0-87938-525-1

Grateful thanks to Domenico Fasano who let me drive his car hard, Sergio Limone and the Baldi brothers for arranging the test.