The Life & Times of American Sports Car Racing Entrepreneur John Edgar, Part 2

In Part One of this story we saw my father, John Campbell Edgar, grow into a man living at the very core of American sports car racing’s Fabulous Fifties. His own austere father had driven him to escape the tedium of small-town Ohio and move to California where, first as a salesman and later as a photographer, John ultimately found his true passion to be the emerging world of sports car racing. With a generous inheritance, he began buying imports in the early 1950s and campaigning them with driving talent Bill Pollack and Jack McAfee. By 1952, Edgar’s modified MG number “88” had become a giant killer with McAfee at the wheel, and Edgar bought his first Ferrari, a 340 America, which Jack raced to victory in the main at Palm Springs in 1953. Next year, John purchased the Ferrari that had just won Le Mans. In the hands of McAfee and co-driver Ford Robinson, this Edgar entry was favored to win the 1954 Carrera Panamericana, but on the first leg of the five-day race its rear end locked, plunging the Ferrari off the road and killing Robinson.

The tragedy devastated my father. He went into a prolonged bender of alcohol and depression, and for a while it looked like he was through with racing. Then, in September 1955, he returned—this time with one of the new Porsche 550s for McAfee to drive. Sweet and fast, the little silver car seemed pure tonic. Getting into the sport again re-energized my father, and he soon bought another Ferrari, an older model 857 S. When the 3.5-liter car finished 2nd to Tony Parravano’s 410 S in the hands of Texas sensation Carroll Shelby, John Edgar realized the newer 4.9 Ferrari, together with Shelby driving, could write a whole new chapter in his sports car racing life.

Photo: Edgar Motorsport Archive

What follows here in Part Two of this story is what happened in my father’s most effervescent years, during that second half of American sports car racing’s golden decade.

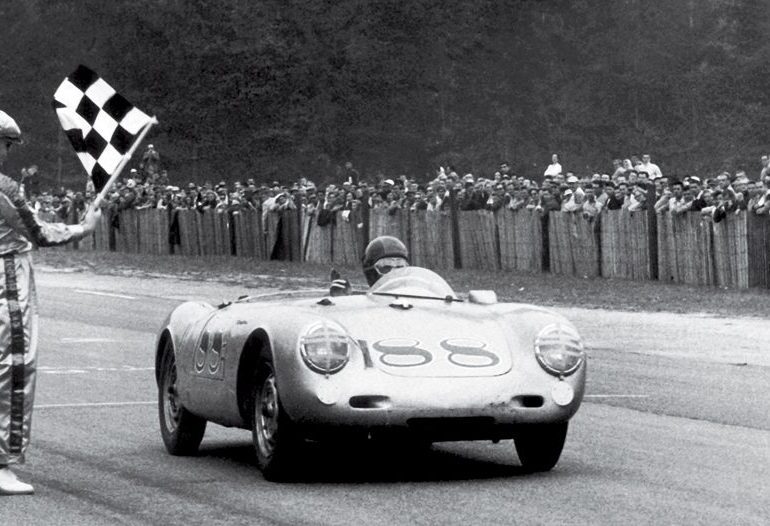

As a revived entrant and rejuvenated by hopes for the new year, John Edgar paired Jack McAfee with Pete Lovely to drive his stock Porsche 550 at Sebring in March of 1956. The chief competition was a factory Porsche driven by Hans Herrmann and Wolfgang von Trips. As Sebring’s half-day ticked on, Edgar’s “California Duo” amazed all by forcing the Germans to “go-for-broke” and over-rev their car to finish ahead of the privateer. At the victory banquet, Porsche’s von Hanstein, humbled by the Edgar Porsche’s stunning runner-up finish to his factory winner, agreed to sell his team’s 550 to my father, on the spot—a car that would prove instrumental in McAfee’s 1956 SCCA Class F National Championship. But there would be more to the year than that, as John Edgar launched efforts toward new heights of spending and festivity.

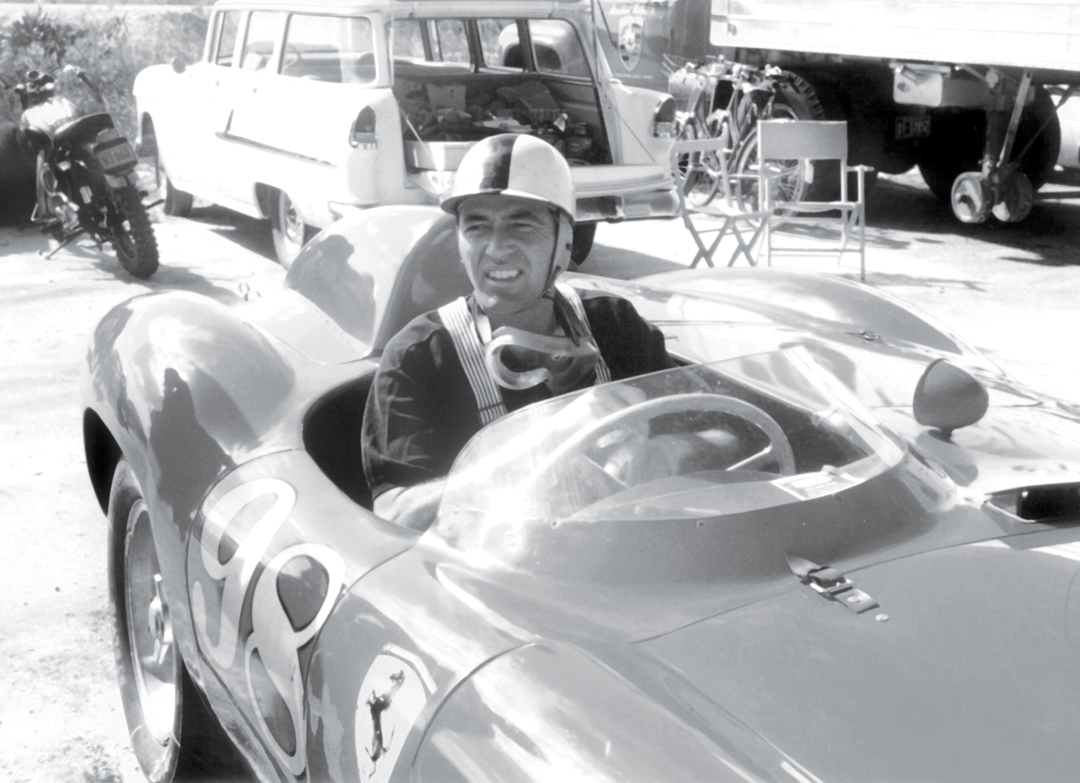

Enzo Ferrari had ordered a special 24-plug 410 Sport (s/n 0598 CM) for Juan Manuel Fangio and Eugenio Castellotti to drive in 1956’s Buenos Aires 1,000 km, but the Scuderia Ferrari entry failed to go the distance, opening the door for my father to buy this exceptional 4.9-liter machine through Chinetti, and give its first American drive to Carroll Shelby at Seattle’s Seafair race on August 12th. Shel won, brilliantly, initiating an owner-driver relationship that would endure for the next two years and cement a close friendship lasting the rest of John Edgar’s life, and carry over to mine for decades more—as Shelby moved on to his celebrated Cobra epoch and stepped, indomitable as ever, into his 80s.

Shel and the Edgar 410 S, during 1956, were unbeatable in every race they finished. After Seafair, he finished 1st over Phil Hill at the inaugural Palm Springs SCCA National in November, a meet where my father entered no less than six cars in competition including drivers Shelby, McAfee, Pete Lovely, Skip Hudson and Paul O’Shea. Victory parties went from the moment of Carroll’s trophy presentation at the airport course, to dawn the next day in the hotel bar and Edgar’s bungalows at the Biltmore, where bongos played until the last eyes fell shut. Also celebrated at Palm Springs, that weekend was my father’s new 10-wheel transporter semi-truck, first of its kind on the West Coast and silver crown of the paddock. The wild Edgar Boy from Troy, whose father told him he could do little, if nothing, right, was sitting on top of a world so foreign to his own upbringing that he might have been on some other planet.

The parties and winning went right on, from California to the Bahamas—Biltmore Lounge to Dirty Dick’s Bar—for my father’s second year there, with Shel driving the 410 S to 1st places in Nassau’s Preliminary, then Governor’s Cup. There the start-delayed race went from sunset into evening on a course marked with black oil drums. Feeling his way through the sultry Bahamian night, swapping the lead lap after lap with the Marquis de Portago’s 3.5 Ferrari, Shelby ultimately won with a blazing 99-mph average in the pitch dark.

Photo: Edgar Motorsport Archive

The Edgar Circus began 1957 at Pomona, in a California downpour, where Carroll got off course and smacked a tree. A hectic 17 days of fixing later, John’s equipe was speeding cross country to Florida’s New Smyrna Beach, where Shel drove the patched 410 S to wins in both the Preliminary and Main— prompting a cablegram to my father from Modena: “MANY CONGRATULATIONS FOR BEAUTIFUL VICTORY TO CLEVER SHELBY = ENZO FERRARI.” Ruth Levy, at Shel’s suggestion that she try a Ferrari herself, rolled it, ending upside down in New Smyrna’s sand. My father shrugged off the damage and promised Ruthie drives in his Porsche 550…So typical of how he was.

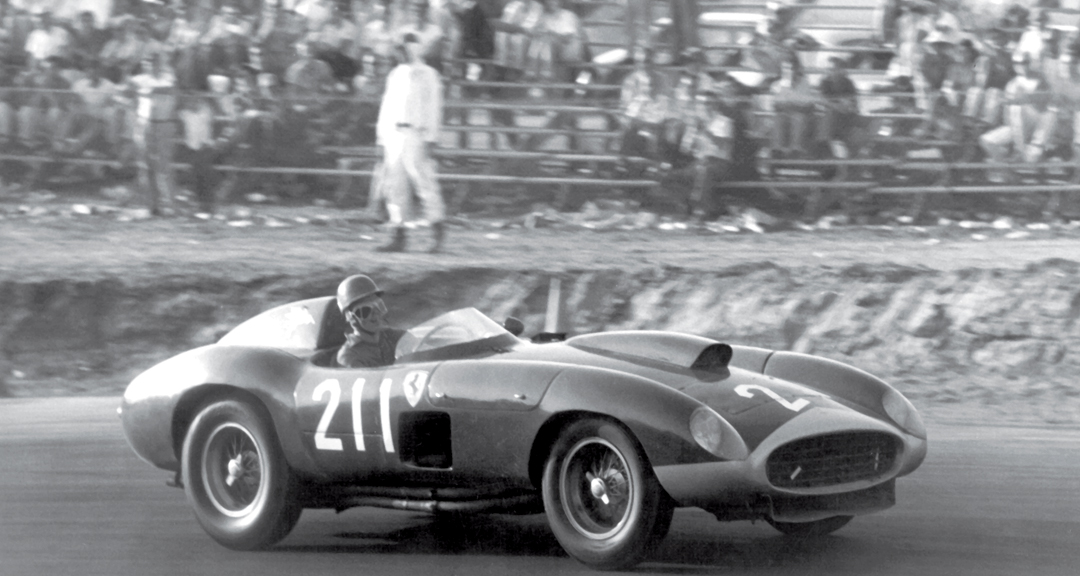

Two weeks later it was on to Cuba. The Edgar entourage—ensconced in suites at Hotel National overlooking the Malecon, where the race streaked past Havana’s shoreline—watched Fangio win in a 3-liter Maserati, while Shelby piloted John’s 410 S to 2nd place after leading a lap early on. Piero Carini, who drove my father’s first Ferrari when it was still a factory car, was not able to finish in Cuba’s other Edgar entry, the aging and now convincingly out matched 375 Plus.

Photo: Edgar Motorsport Archive

For his return to Cuba in 1958, John was back at the National shooting 16-mm home movies of Ernest Hemingway, highball in hand, on a room balcony below the Edgars’. It was a festive, bright day in February. Masten Gregory had been given my father’s 410 S, with Shelby in the new Maserati 450 Sport. Thousands of cheering Cubans lined the 3.5-mile street circuit, but Havana’s Grand Premio was cut short by a deadly accident. Rebel followers of Fidel Castro, trying to wreck the race and embarrass the government of Fulgencio Batista, threw oil on the course in front of approaching cars. On Lap 5, Cuban driver Armando Garcia Cifuentes’s 2-liter Ferrari skidded and slammed into a pack of spectators at 100 mph—killing five and injuring 32. The GP was halted and Stirling Moss in a Ferrari 335 S declared the winner, with Gregory and Shelby 2nd and 3rd. The incident, along with the bizarre rebel kidnapping of Fangio which kept him from entering, spelled the end of sports car racing in Cuba. In less than a year, Castro would seize power.

Backtracking, if you will, to February 1957—and Fangio’s Maserati victory in Havana—my father first got inspired to look to Italy’s “other marque” to freshen his racing stable. He wanted Maserati’s big, new 450 S, but the factory shipped him a smaller 3-liter car instead, hanging on to their more powerful 4.5 for the works team—with a promise, thank you very much, of sending it to him later. It was déjà vu, as shades of Ferrari’s earlier bait-and-switch came into play once more—now with the trident badge instead of the horse. But how bad was it, really? This smaller 300 S (s/n 3071), with Stirling Moss and Harry Schell driving, had finished 2nd to Maserati’s other team entry—Fangio and Jean Behra in the 450 S at Sebring in March. Now, in early April, in John Edgar’s own car, Shelby won the Palm Springs Preliminary with this ex-works 3-liter Maser, but then lost by a devastating 49 seconds to Phil Hill’s heady 4.4 Ferrari Monza in the next day’s Main. Not what my father had in mind, not at all. And right away he had to rush off to the First Annual Hawaiian International Sports Car Speed Week at Mokuleia, Oahu. He took his Maser and Big Enzo-mobile with him.

Photo: Edgar Motorsport Archive

John Edgar’s contract with Modena’s Officine Alfieri Maserati—making my father the marque’s U.S. racing representative—forbade his entering a Ferrari in regular road race competition, so once on Oahu he gave the 410 S to Phil Hill to drive in the meet’s speed trap contest for individual cars. Phil reached 165.12 mph on Dillingham Field’s 3,800-ft. Mauka Straight for the winner’s certificate—then, while the 4.9 just sat, Shelby drove the 300 S to 3rd place in the meet’s Gold Cup Challenge. Meanwhile, John was 30-miles off at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel, schmoozing with dime-store heiress Barbara Hutton after she’d flown to Waikiki to see her son Lance Reventlow, who was to drive another of my father’s cars, the Porsche 550 originally slated for former raceboat star Tetta Richert, sister of the Hawaiian race organizer. If it all sounds thorny, it was. This convoluted scenario might have rivaled a Marx Brothers movie, were it not for the heartbreak of Lou Brero’s death resulting from his fiery accident during the Main on Easter Sunday.

From Hawaii, my father’s non-stop 1957 calendar charged on into May—Ruth Levy winning the ladies race at Santa Barbara in his Porsche 550 and Phil Hill finishing 3rd in the Main there driving the Edgar 410 S, while Shelby won that same day in John’s 300 S at Cumberland, Maryland, only to win again a week later at Cotati in California, and win yet again, back on the East Coast once more, at Lime Rock in early June. Meanwhile, Joe Landaker, my father’s truck-loving mechanic, was wheeling the big Edgar transporter “hammer-down” from one venue to another—and cited for doing 110 mph in Texas as he sped toward Dallas, where Shelby would fail to finish in the Maser. The pace was costly both in terms of my father’s health and outgoing dollars. But he was on a roll, and nothing would stop him. By July, Shelby got his hands on the promised 400-horsepower 450 S Maserati (s/n 4506), right away winning with it at Lime Rock at the end of July and scoring a 1st at Virginia International Raceway’s inaugural, only a week later.

During this madcap “racing-to-race” my father also had decided to bankroll a vision of sports-car-buff and restaurateur Rudy Cleye, and was pouring cash into a new concept track outside Riverside, California, slated to open the third weekend in September. Its layout, among the gentle slopes of a former turkey ranch, promised to be a literal end-all of road race courses in America. But time grew as scarce as its departed turkeys. “Not finished by a long sight”—were my father’s exact words when, on September 21, 1957, the track somehow opened as scheduled for a California Sports Car Club meet. Edgar entered his Maseratis—3-liter and 4.5-liter—and placed his 4.9 Ferrari 410 S in the gloves of Richie Ginther, who had driven well and won often for John von Neumann. When Shelby crashed the big Maser in practice, with damage and injury sufficient to keep both car and driver sidelined, Bill Pollack took the little Maser to an astounding 3rd in the Main behind Bill Murphy’s burly Kurtis-Buick. The real feather in my father’s cap came with the winner that opening day at Riverside—Ginther took 1st place on “John’s track” driving John’s Ferrari, voted earlier that year “The best over 1,500-cc racecar in America.” Well, my father was beyond ecstatic. And the Riverside revelry wasn’t over—not yet.

Shelby, after winning the Preliminary in early November at brand-new Laguna Seca Raceway while once again driving my father’s 3-liter Maser, came back to Riverside for the track’s first SCCA National in mid-November. It was a bitterly cold weekend but Ol’ Shel was hot stuff. He drove a classic, never-to-be-forgotten race in John’s big 4.5 Maser, spinning early, then thrashing his way to catch and pass everyone in the fading light of afternoon, to win five seconds ahead of Frank Arciero’s 375 Plus driven by a local newcomer named Dan Gurney. As cameras flashed in victory circle, John Edgar couldn’t ask for anything more.

From the Mission Inn to the Emerald Beach—it was back to the Bahamas, where my father closed out his 1957 racing spree with Shelby in the 4.5 Maser finishing 2nd in the big event behind Stirling Moss’s 4.1 Ferrari. The exhausting year, and upcoming Havana disaster already described, took a heavy toll on my father’s stamina and enthusiasm for the game. With Maserati citing money problems and retiring from racing at the end of 1957, the new year saw John Edgar at few events with even fewer respectable finishes. His last victory of significance was Nassau in December 1958, where Bruce Kessler won the Ferrari Race driving John’s old faithful—the acclaimed 410 Sport that Enzo built for Fangio so many races, and so many wins, before. My father had that sense that this was it, that it was almost over—time now to think about leaving.

As the 1950s wound down, a coming of professionalism was striping the old gaiety from sports car racing in America. That, and the gratification of having been a major player during the golden decade of the Fabulous Fifties, closed a rewarding chapter in John Edgar’s life. Still—to use Hemingway’s phrasing—it left an emptiness. By March of 1960, my father had sold his cars and his interest in Riverside Raceway, repairing to his new home on a city-view knoll in Beverly Hills where he and my mother lived until their deaths from cancer, she going in 1968, he in 1972. In those final years, Carroll Shelby remained a friend and frequent visitor, and old Joe Landaker of Edgar-transporter fame came by to sit and talk now and then about the racing they had all done together.

What my father, in the 1950s, gave me was that great gift of being there with him so often at the races, and those inexorable soirees—both orderly and not, respectable or otherwise—that accompanied them. The years also left me with a wealth of memories and valued memorabilia, today the foundation of a period racing archive known as Edgar Motorsport, made available to media use and motor journalism of this variety.

Last December, at the annual Fabulous Fifties Association gala at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles, I took to the podium for a few after-dinner words about my father in the 100th year of his birth. I saw many fine and familiar faces in the audience. Carroll Shelby and Phil Hill, Ruth Levy, John von Neumann and Bill Pollack, among others—and John Fitch and Mary Davis, for whom the evening offered special honor. About my father’s place in the 1950s, I added this:

Photo: Edgar Motorsport Archive

“He so freely provided the equipment and aura that helped make those celebrated years exciting and fun, and at times a bit bizarre, stretching from his little MG TC the McAfees built and raced, through his scrappy Porsches and mean-ass Ferraris and thundering Maseratis that Jack and Shel and Phil and Ruth drove—to the advent of Riverside Raceway. He was in the thick of it all, as John Edgar himself would say—‘like nobody’s business.’”

William Edgar co-authored the award-winning American Sports Car Racing in the 1950s with Michael T. Lynch and Ron Parravano.