The Life & Times of American Sports Car Racing Entrepreneur John Edgar, Part I

Photo: Edgar Motorsport Archive

Edgar was our name. One of my earliest memories of my father is this—tall, bald, glasses, at the wheel of a car with a long blunt hood with fins going around it. I liked to draw pictures of us going fast down our street in Toluca Lake. We sped around the corner where Lon Chaney lived and went over to the big studio by the river where Bing Crosby worked. The car had funny headlights that folded up, and the dashboard was a lot of little metal circles that looked like whirlpools, and the leather seat smelled good when I buried my head in it so the sun wouldn’t shine in my eyes. When my father drove the car, he laughed and I did too. My mother drove it sometimes, and when she did, she looked like one of the movie stars we used to see at Lakeside Market. The top went back and the wind blew in, and we called it “The Cord.” It was 1938 and I was five.

John Campbell Edgar, my father, was a star salesman then. He sold commercial kitchen equipment in Los Angeles that was made at a factory his father and some other men founded three decades before in Troy, Ohio. One of them was named Hobart, and that was what they called it. They first manufactured electric coffee grinders and then meat slicers and food mixers, and their consumer machines were called KitchenAid. We had one of the big chrome plated mixers in our house that I used to sit on like it was a horse.

Photo: Edgar Motorsport Archive

Photo: Edgar Motorsport Archive

Before we moved to California, we lived in Troy where my father grew up. He was a wild sort, the only child of Edwin – everyone in town knew him as “EE” – and Bessie, who taught at the old brick schoolhouse. “Johneeger”, as he was called then, loved cars right from the start, being born about the same time they were. His first was a Mercer when he was still in college. And he rode a motorcycle. He always told the story about how he hit a pig with his Henderson and went flying over the handlebars and down a gravel road on his bare palms. Later, he had a hopped-up Model T with a Rajo head that went like a bat out of hell. When he married my mother, GiGi, he bought a Chrysler Crown Imperial roadster and used it to tow the outboard hydroplanes that he raced on rivers all over the Midwest. That is before he drove the car through a farm fence one night after a Roaring Twenties party. He was sharp in the boats and went on the national trail, racking up points towards a championship by the time my brother was born and I was due. The end of his outboards came on Biscayne Bay in Florida. Leading the 1932 speed regatta, a wind gust lifted his hull and blew it high and over, dropping him out to the water. The boat came down on top of him. All of his ribs were broken, and he lost a kidney – but he would never lose his love for speed.

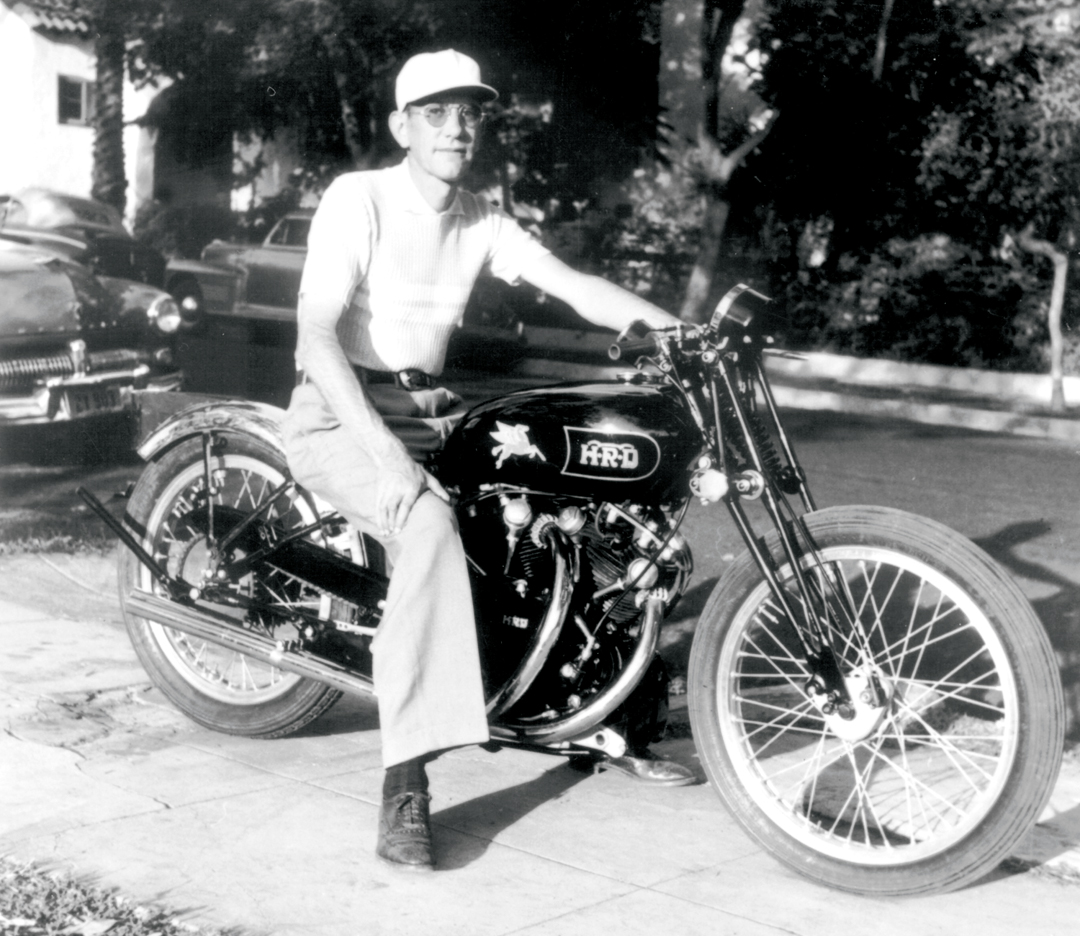

After moving to California and buying the Cord, then moving back to Ohio right before the war, then back to California again in 1943, John Edgar, whose father had died two years before and left an inheritance, was one of the first to own an MG TC in 1947 when they started coming over from England. His was red and came from a shipping batch of 20 other red MGs… all used the same ignition key! And he loved driving it. He was also riding motorcycles again – this time an Iskenderian-tuned, speed trophy-winning Triumph Tiger that only made him want something faster. The answer came from where his MG did, across the pond. He had Britain’s Vincent HRD factory build him what was to be its first “Black Lightning,” and John asked American speed traps rider, Rollie Free, to break the record with it at Bonneville. Everyone knows the picture of the guy in bathing trunks laid out flat on the bike – Rollie’s innovation for setting a world’s flying-mile record 2-way average of 150.313 mph for unfaired motorcycles in September 1948. It was great for my father. He immediately de-tuned the V-twin from alcohol back to gas, slapped on fenders and saddle, and rode the record bike on the street. I got the Triumph, with my brother, Jack, rounding out our riding trio on an Ariel single. What a dad we had.

Photo: Edgar Motorsport Archive

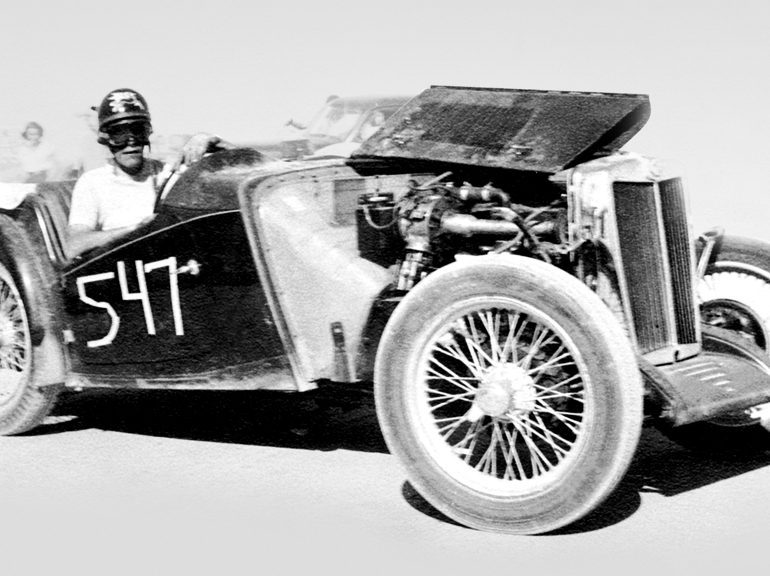

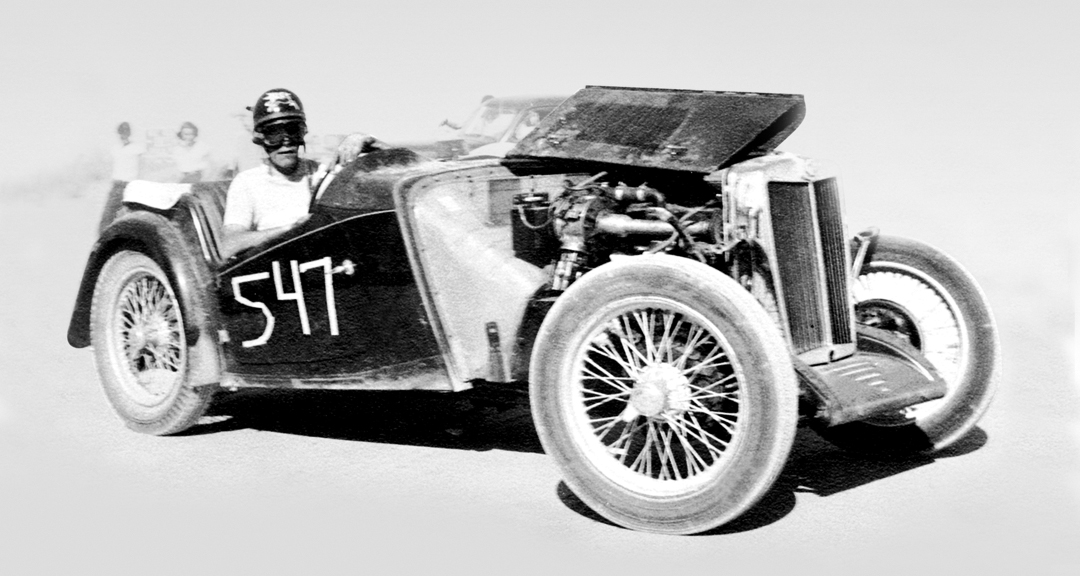

In no time, John Edgar was looking again to four wheels for thrills. He had his motorcycle pal, Ernie McAfee, install an Arnott blower on the TC, making it, in my father’s hands, the fastest MG at El Mirage dry lake in October of 1948 and a feisty demon at local hillclimbs. A year later, John was driving a drophead Bugatti, importing Italmeccanica superchargers from Italy, and – along with dozens of other McAfee-inspired modifications to the MG – the Arnott was replaced by an intercooled I.T. blower, and the MG entered in the Santa Ana blimp base road races in June 1950. Two months earlier, at the inaugural Palm Springs Road Races, my father had watched Ernie’s friend, Bill Pollack, drive the hell out of his own MG, so John asked Bill to race his at Santa Ana. The entrant-driver duo of Edgar and Pollack was soon off and running on a string of mighty MG conquests. In the annals of John Edgar’s involvement with American sports car racing in the 1950s, it was only the beginning.

At this point in his story – lest we lose sight of the man while seeing perhaps too much of his machines – John Edgar requires deeper characterization before going further. Although bystanders often saw my father as a joker and wastrel, he was indeed a brilliant thinker able to understand the complexities of mechanics and engineering that escaped many peers who, like he, could afford the cars and costs of amateur competition, which road racing in most of the ’50s was. Despite what could appear to be a decade-long spree of free-spending on his behalf, my father had to balance the assets of inheritance and his own shrewd investments against galloping expenses of campaigning racecars and winning trophies, and he did it with astounding acumen. In addition, whether by design or not, he was helping build a solid foundation for our sports car racing of 50 years ago that would benefit participants for decades to come, as we will see here in his quality of cars and drivers and, ultimately, his funding of Riverside Raceway. Also, not forgotten by those who knew him well and relayed to those who did not, John Edgar had the fever for racing that makes the sport – in its best of form – so enjoyable and rewarding.

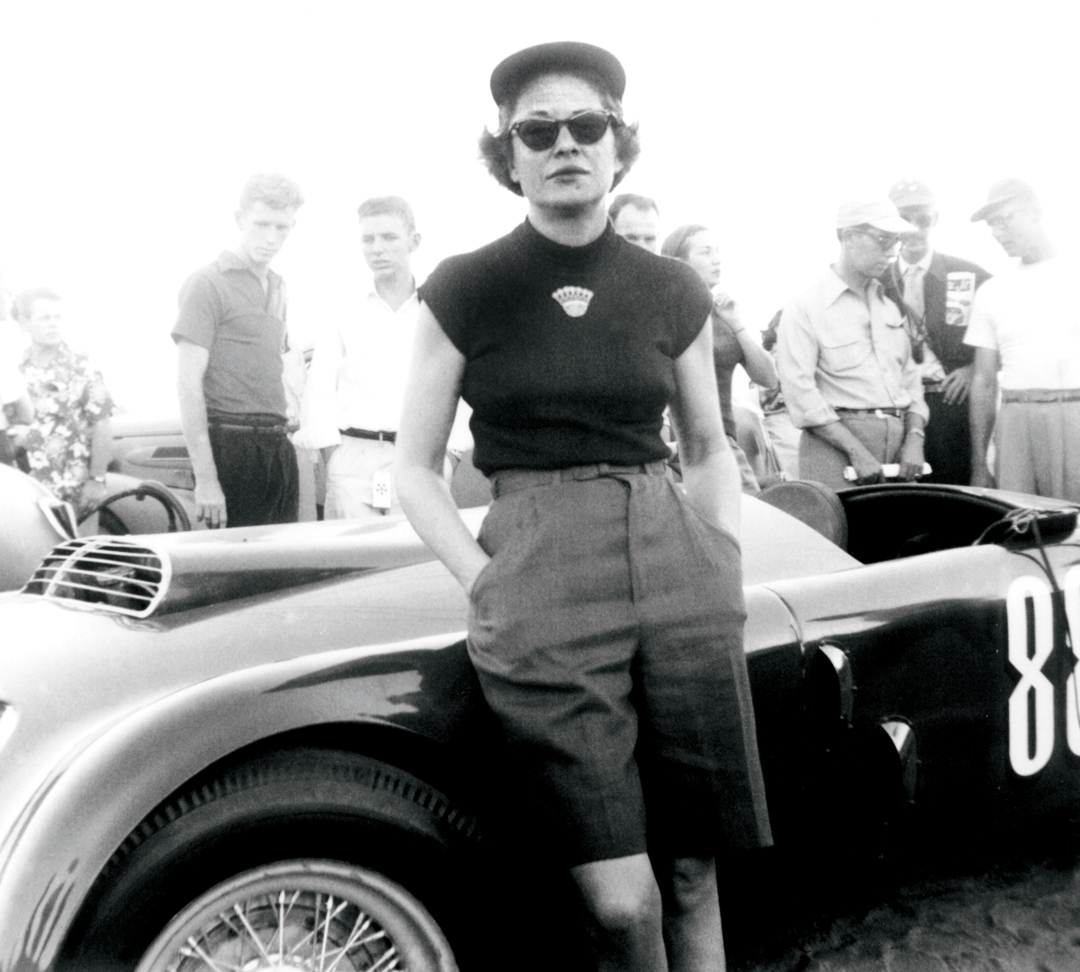

The Edgar MG, with mounting recognition, knocked the socks off California’s sports car crowd. In the hands of Pollack and former dirt tracker, Jack McAfee, MG #88 was pure dynamite, but my father typically tired of it and advertised the car for sale in June 1951’s Road & Track. He asked only $4,500. But buyers were looking for newer stuff, and the lag time was enough for the non-related McAfees, Ernie and Jack, to convince John to go forward with their ultra-modification plan that included special enveloping bodywork by the master, Emil Diedt. Sleek and eye-catching, the result debuted at Palm Springs in October 1951, and “88” quickly gained the reputation as a giant-killer, even racing toward the next decade under new owners. The car was finally crashed and burned for a movie scene in Stanley Kramer’s On The Beach. Like so many outstanding specials of those times, this was a gem lost through hands that knew no future.

Photo: Edgar Motorsport Archive

In the early 1950s, it can be said of John Edgar that he was “Ferrari-driven” – and he went after those powerful red cars with a craving. In 1952, he bought his first from Henry Manney, a 340 America, and at 4.1 liters, it was the earliest of the large-engine Ferraris to make the racing scene. Manney had brought the ex-factory team car to the U.S., and, with its fancy show treatment around grill and headlights, “Serial Number 0032 MT” was a beauty to behold. As soon as John got his hands on it, he took the 300-horsepower stallion out on Hollywood’s Cahuenga Pass, a section of concrete freeway near Ernie McAfee’s shop, and ran it up to 140 mph. This was exactly what he wanted – a Ferrari he could drive on the street and still have Jack McAfee race. John immediately built an enclosed hauler for his ruby jewel, got out road maps, and began entering it in races both in and out of California. In March 1953, “Big Jack” McAfee shot down Bill Stroppe’s strapping Mercury-powered Kurtis with Edgar’s 340 and cleaned the field at Palm Springs, then grabbed 2nd at Phoenix in May, and won again at Willow in November. As good as it appeared to be, the 4.1 was already getting race worn, and newer, better Ferraris were coming to the grid.

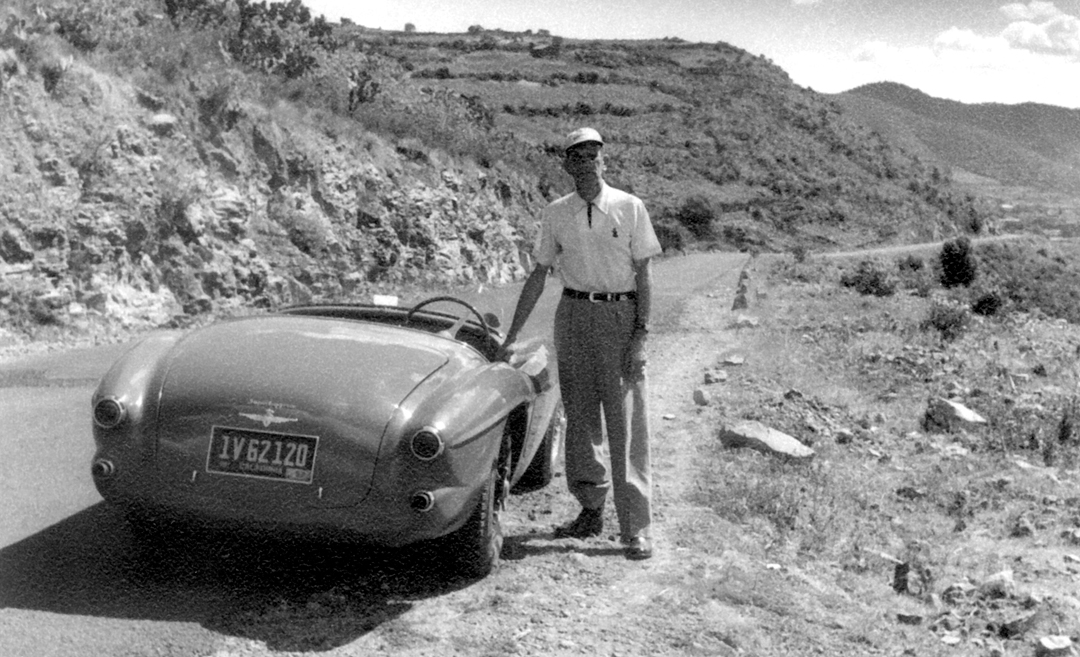

With the forming of John Edgar Enterprises in October of ’53, to umbrella expanding racing affairs, my father’s Ferrari appetite intensified. Sports car competition had become serious business for him, even though the pursuit was still strictly “amateur” in support. Through a developing relationship with Luigi Chinetti (Enzo Ferrari’s man in New York), John arranged to buy the 4.9-liter, long-wheelbase, 1954 Le Mans-winning 375 Plus for Jack McAfee to drive in that year’s 5th Mexican Pan-American Road Race, with Jack’s buddy from hot rod days, Ford Robinson, as co-pilot for the 1,908-mile road race. This ex-factory car (s/n 0396 AM), victorious at Le Mans in the hands of Froilan Gonzales and Maurice Trintignant, was both beauty and beast. Its V-12 power, rated 344 bhp at 6500 rpm, was considered staggering in those days and, unlike standard 375 MMs, the 375 Plus’ transmission was designed in unit with the differential to give the car better overall balance while its de Dion rear axle promised optimum roadability for the major haul. The Mexican race was to be a grand adventure for my father in his 53rd year, and he had long planned for it. Two years before, “to scout the way,” he took my brother, Jack, on a wild 4.1 ride, screaming down the Pan-American Highway as far south as Mexico City before both car and driver were exhausted by the ordeal and too many cantina stops. At one point, they drove under a hay wagon, emerging heads down on the other side…throttle on!

Photo: Edgar Motorsport Archive

Working night and day throughout early November 1954, John’s 375 Plus, sporting a factory-mounted extra fuel tank for the arduous 5-day race, was further made ready by McAfee, pumping up muscle to 380 bhp. My grandmother’s adored ’41 Cad limousine, “Tillie”, would serve as conspicuous hauling vehicle for spares, with a spanking new GMC pickup towing the Ferrari to the southernmost point of the race where it would start in Tuxtla Gutierrez, Chiapas. Meanwhile, my mother’s powder blue Mercedes-Benz 300S cabriolet was fitted out as John Edgar’s personal chase car. Ford Robinson, McAfee’s co-driver, would shoot in-car film and sound for NBC News. Number “1” boldly adorned the big Ferrari’s flanks while McAfee was named in decal as “La Bala” (The Bullet) and Robinson “El Zorro” (The Fox). But this elaborate, favored-to-win scenario had its tragic denouement. On November 19th, moments after running flat out at 208 mph on Day-1’s notorious Tehuantepec Straight, the 4.9’s rear end locked, presumably from an overheated differential bearing, pitching the Edgar Ferrari off the road and into the tangled Oaxacan jungle. McAfee survived with minor injury, but Robinson was killed.

My father was devastated. Death had always been near in racing – he’d barely escaped it himself in his hydroplane accident. But this was right there, one of his drivers in one of his cars. An intermittently heavy drinker for years, John Edgar now went on a month’s long bender of alcohol and depression that led him close to the grave himself. Why did he torture himself this way? Why did he at times drink to death-defying excess? For answers we invariably look to background and upbringing. My father’s father, a circuit minister’s son, was a severe authoritarian, critical to the point of obsession. Whatever John did, no matter what, was scrutinized and challenged by EE Edgar. Rather than let his son go off with friends to Yale where he might study toward becoming a writer, EE made him attend humble Denison, a short distance from Troy – so the elder Edgar could maintain a watchful eye. When it was time for John to join the Hobart staff, EE, a director and general manager of the firm, brought him in not as the junior executive he was so well qualified to be, but rather as underling to a clerk a foot shorter than the tall and brilliantly capable young lion. My father interpreted it as an act of meanness that he never forgot.

Photo: Edgar Motorsport Archive

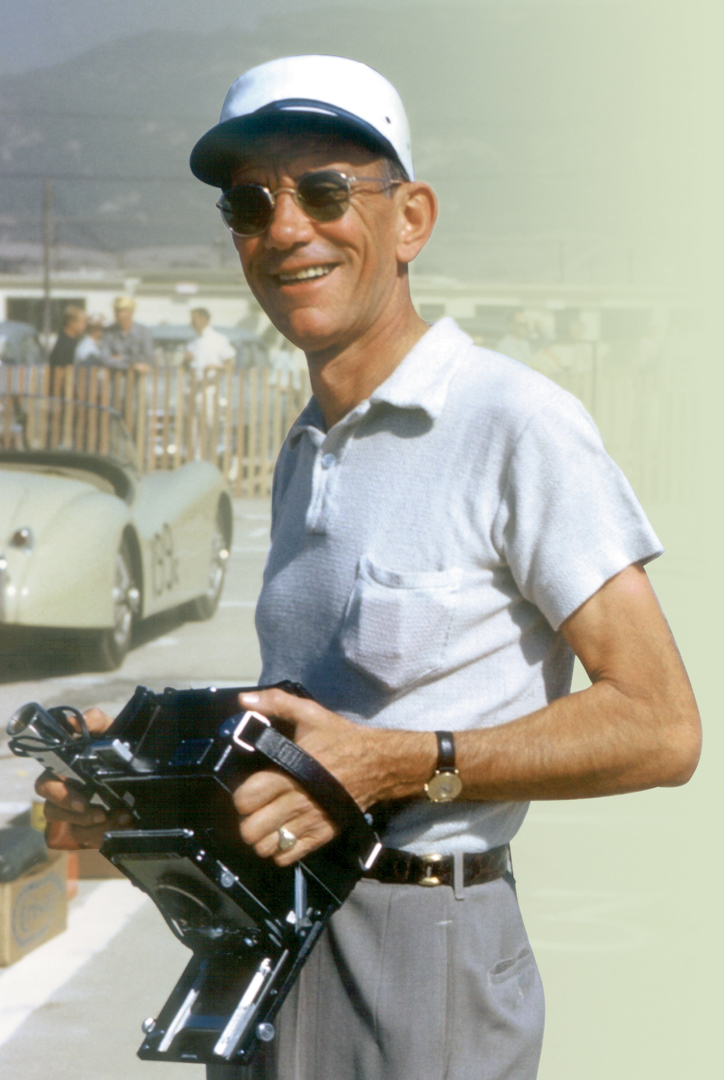

John’s eventual breakaway to California in 1935 was to show EE he could sell Hobart equipment and beat his peers hands down at the game, and he did just that, becoming the Pacific Division’s top salesman for 1937. Four years later, struck with pneumonia in his 70th year, EE died at his winter home in Miami Beach. The reality of it was that John would have the freedom and money now to do what he wished – and it was his task to decide. First it was photography, then investments and importing. Ultimately came the sports car racing scene, a passion spilling over into his business world.

It was not until six months after Ford Robinson’s death that John Edgar sobered up and came back into racing, buying not another Ferrari, but this time a Porsche 550 Spyder – one of the first in America – for Jack McAfee to drive in under-1500 cc races. The little silver car seemed a tonic after the Mexico crash, and Jack described the German speedster as being sheer pleasure to drive compared to wrestling the Italian made brutes through the twisty tests of American road racing. But, the big 4.9 Mexico car also was back again in the Edgar stable, having been in Italy for repair and re-body by Scaglietti. Jack found himself in this 375 Plus once more and making an appearance at Nassau in December 1955, to place only 5th and virtually finish the car’s days under Edgar ownership. Years later, it would be re-bodied back to its original 1954 Pinin Farina silhouette and stand in a collection of revered Le Mans-winners.

Inevitably, then, along came John’s third Ferrari. My father ordered a 3.5-liter 4-cylinder car, convinced it would be one of the new 860 Monzas he could run at the 1956 Sebring 12-Hours. To his surprise the factory sent s/n 0588 M, a prior design 857 S, reputedly the last one they had. My father was not a bit happy but entered the car anyway at Palm Springs in February. Jack McAfee drove it to 2nd behind Tony Parravano’s latest threat from Maranello, a torrid V-12, 4.9-liter 410 Sport piloted by the 33-year old sensation out of Texas, Carroll Shelby. This mismatch of Ferraris at Palm Springs opened my father’s eyes wide to a need for beefier red stuff than meager four-bangers.

He also took notice that Shelby shone like a second sun in the California desert.