1969 Chevron B8-BMW

In my book, 2006 was a good year. Got my pensioner’s bus pass, had two cataract operations, made my Le Mans debut…not necessarily in that order! I can only now reveal that it is possible to race at Le Mans with one eye! This may come as a shock to the team.

The chance to finally race at Le Mans came courtesy of John Ruston and Gareth Burnett who had recently found a tidy and quite significant Chevron B8 and were about to use it as part of a serious team effort at the Le Mans Classic, now regarded as the historic race to take part in…well six races to take part in. The Patrick Peter organization has built up this event extremely well over the few years it has been running and it can now boast a staggering entry. It was well oversubscribed for 2006, an outcome of only running the event every two years. The format, as most of you now know, is to have six grids of up to 72 cars, each spanning Le Mans history from its origins in 1923 up until 1979. Each grid has three 45-minute races and positions are judged on both outright position and index of performance. Teams consist of one car from each grid. Preference is given to cars with genuine 24 Hours history or competition versions of the same models. The Le Mans Classic has become a real showcase of Le Sarthe history, and this year there was also a celebration of the Ford victory 40 years ago, with a reenactment of the finish of that race.

John Ruston had entered several cars which were being looked after by GB Race Engineering: two Talbot 105s, BGH 21 and BGH 23 featured in the January issue of VR, in Grid 1, Stanley Gold’s Porsche 904 GTS being shared with James Diffey in Grid 4, our Chevron B8 and a Porsche 910 in Grid 5, and Gareth driving the famed Chevron B26 “Chocolate Drop” in Grid 6…the ex-Gethin/Redman machine from 1974. This was an exceedingly ambitious project, and meant that team boss Ruston, Gareth Burnett (down to drive in nine races), and chief mechanic Neil Bailey would get little sleep over the weekend. My B8 co-drivers Gareth and Caterham Champion Luke Stevens would also be working on the cars, so really I had the easy job…just go out and drive.

The Chevron B8

The chance to drive a Chevron B8 at Le Mans had a rather special meaning for me, as back at the end of 1971, I had put a deposit down on the slightly earlier B6 model, also with a 2-liter BMW engine, but my then race partner had chosen the same day to order two Formula Ford Mirages from John Wyer himself. I got my deposit back (!) and we went Formula Ford racing in 1972. Well, we all make mistakes. I did, however, get to drive Robin Smith’s Chevron B19 in Angola in 1974, and that was something of a unique achievement, as a rather serious war was just starting in that now-infamous and beautiful West African country.

Back in those days, Chevron had become virtually a household name. Since Derek Bennett had produced his first two Clubman B1 models in 1965, until his untimely death in 1978, Chevron had penetrated almost every class of racing: Clubman’s, GT and sports cars, F3, F2, Formula Libre, FB, Atlantic, F5000, Super Vee and even Formula 1. Chevron won 32 racing titles between 1967 and 1986 in the UK, Europe, South Africa, USA, Canada, Angola, Australia and New Zealand.

Born in 1933, Derek Bennett grew up in a suburb of Manchester, in very modest circumstances, moved with his family to Yorkshire during the war, and then returned to Manchester. It was not unusual for the young Bennett to cycle 30 miles to visit his wartime friends in the Pennines. Like many British boys, the war had inspired a lifelong interest in aircraft, and young Derek not only became an expert model builder and flyer, but learned aviation principles which found their way into his later car construction. He learned the basics of car building by setting up a garage in Bolton, in Lancashire, where he mainly repaired accident-damaged vehicles, often by welding two undamaged halves of cars together! During this period in the 1950s, he also found his way into motor racing with his own home-built machines, and attracted some race-oriented customers, as he was also a good driver.

Race driver Brian Classick, later a well-known dealer in historic vehicles, was a fan and commissioned Bennett to build him a clubman’s racer, with a tubular space-frame. Bennett had no training as an engineer…all his ideas were summoned from his own thoughtful and analytic mind. He became renown for not using any drawings, and his first product won a race in Ireland in 1965 “straight out of the box.” A characteristic of the clubman car was that Bennett found and used the best combination of available “bits” to bolt on, a throwback to his car repair days, but it always seemed to work.

The name Chevron did not appear until after several cars had been built. They were first known as Derek Bennett Specials, but it was Brian Classick who forced professionalism on Bennett and he eventually stumbled across the word “chevron” in the Highway Code manual and it stuck. The model designation was retrospective from 1968, so the first two clubman series became known as B1 and B2. A total of six of these cars were built and Bennett started thinking about something to beat the then-dominant Lotus Elan in GT races. Customers wanted him to build a clubman with a roof, but instead he began to develop the idea of a “proper” midengined coupe. He got so far as carving his concept in balsa wood and kept it on his desk. Racer Alan Minshaw, later to become “Mr. Demon Tweeks,” saw the model and encouraged Bennett to build it. Minshaw put down a deposit, but when he found out the car would be a bit more than the £1,700 he was expecting to pay, he suggested that another up and coming racer, Digby Martland, should visit the workshops and talk to Bennett. He saw the model and took over Minshaw’s order. One of the reasons the model was so impressive was that it had been worked on by Bennett’s old aeromodeling friend Bob Faulkner, who was now working in the aviation industry. This pair knew and discovered a vast amount about aerodynamics from their own fascination with aircraft, perhaps even more than Colin Chapman had done.

Bennett then set to work on designing what would eventually become the B8, a car that had a tremendous influence on GT and sports car racing for a number of years. He designed and constructed the space-frame chassis, rear uprights and wishbones, but virtually all the other mechanical components were sourced from a variety of road and racecars, as was the custom at the time. Influenced both by his experience and knowledge of Ford and BMW engines, and by what was available, Bennett decided to develop two engine options, at least at the beginning of the project. A 1.6-liter Ford twincam, exactly as used in the Elan, went into B3 for Digby Martland, and the unit from a BMW 2002 road car was deployed for B4, which was to be Bennett’s own race and development car. Both cars had lovely and graceful aluminum bodies. When completed, Peter Gethin did the early testing on the Ford-engined car, and was immensely impressed. Within a few days, Martland had a winning debut race at Oulton Park on July 6, 1966, another “straight out of the box” victory. These cars were generally referred to as Chevron GTs at the time.

A second Ford-engined B3 was built for John Lepp and the three cars had numerous successes through the end of 1966 and into 1967. In effect, they made the Elan obsolete virtually overnight in GT racing. A good showing in February at Daytona by Gethin, Roy Pike and Fred Opert brought in more orders, and Bennett decided to have the bodies made in fiberglass by Specialised Mouldings. An arrangement for the supply of 2-liter BMW engines was set up in Germany, and this was a major move for the company. David Bridges, however, had a car built with a 2-liter BRM engine for Brian Redman, this being the only B5, and this car was another maiden race winner at Oulton Park in April 1967, and further wins really made Chevron’s name. Digby Martland had also had a good result at the Nürburgring 1,000 Kilometers.

In 1967, seven B6 models were built, six with BMW motors and one with the 1.6 Ford. These cars won a vast number of races during the year, as well as the UK Motoring News GT Championship for John Lepp. With more orders coming for 1968, Bennett decided to seek Group 4 homologation so the workforce was expanded to build the necessary 50 cars. In fact, only 44 of the new B8 were built between 1968–70 but, as the earlier cars were so similar, they were allowed into the count by the FIA, as only the serious intention to build 50 cars had to be demonstrated. Bennett had had to modify his early BMW engine with his own sump so this unit was now running reliably. Martland and Classick finished 8th at the BOAC 500 a few weeks before the homologation was approved in May.

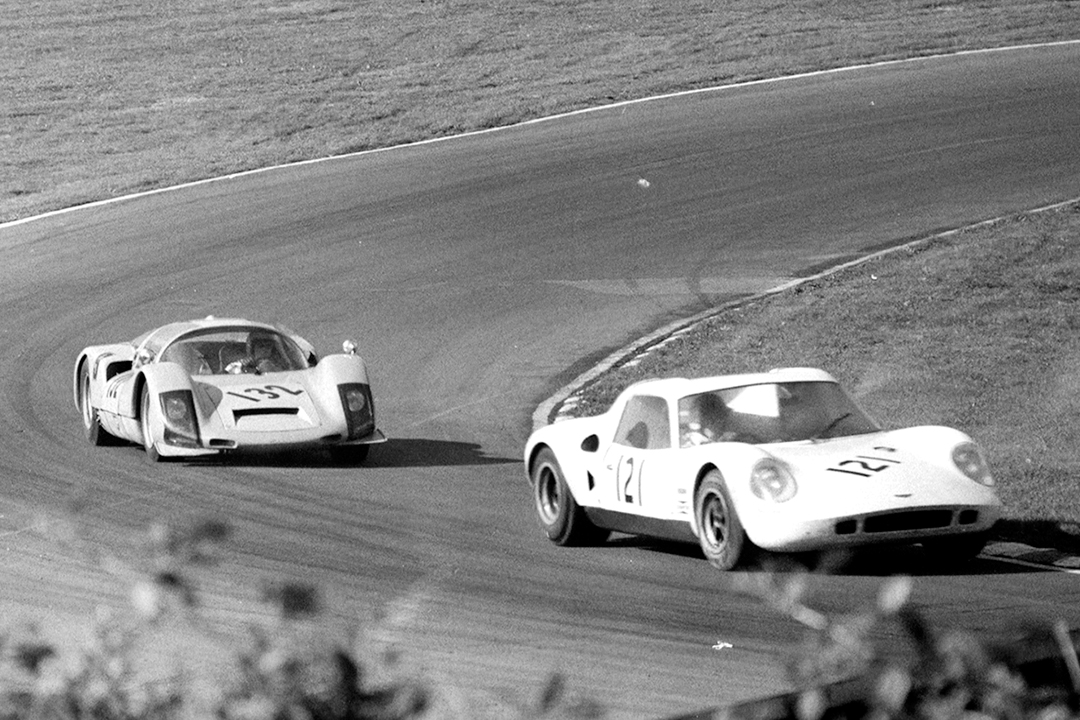

Seven of the new cars were at the Ring for the 1968 1,000 Kilometers, and they were competitive but were not quite on the pace of the German Porsches. However, the B8’s first win came at Silverstone and Barrie Smith won the B8’s first international race outright at the Jyllandsring in Denmark in August. Chevron B8-BMWs were appearing in a wide range of British and international events, and had become very successful cars for the sports car privateer. John Lepp would go on to win the RAC British Sports Car Championship in 1969 in his B8. The Chevron workforce which had built the new B8s was partly made up of a number of Bennett’s friends and acquaintances, many of whom worked odd hours and two jobs. The Bolton factory was always a convivial place, with Derek always on the shop floor. The team would work long hours and then end up in the local pub.

By 1969, Chevron was also a threat in international F3, with Reine Wisell as a works driver, driving both the F3 and the works B8 in sports car events. The 1969 car was built to be stronger and safer, and Bennett masterminded improvements to the BMW engine so it was now producing maximum power. There were bigger valves and changes to the head. The B8 now had bigger brakes, wider wheels, new shock absorbers and an adjustable front anti-rollbar. The car was still some 45 bhp behind the Porsche 910, which presented problems on circuits with long straights. Nevertheless, the B8 was always competitive on street circuits and tight courses, and it could embarrass the Lola T70, Ford GT40s and Ferrari 250s while winning the 2-liter class.

At Easter, the RAC Sports Car Championship had a round at Thruxton. Sports car privateer Paul Vestey had entered his new B8, chassis DBE 71, for the rising star of Formula Ford and Formula 3, Australian Tim Schenken. Charles Lucas was leading the 2-liter class in his B8 but had a spin and Schenken went on to a notable victory in the class, leading John Burton’s B8 by a good margin. The Thruxton race was a warmup for Schenken, as he was to drive the car in the following weekend’s BOAC 500 at Brands Hatch. He was to share our test car, DBE 71, with John Fenning and was considered a strong choice to at least win the class.

During the first day’s practice, however, a track rod link came apart at the exit of Clearways and the car headed into the bank and rolled several times. Schenken was happy that the B8s had been strengthened and he was unhurt, but the car was definitely out of the race. Wisell in the works B8 with John Hine had a tough battle for the 2-liter class with the VDS Alfa Romeo of Pilette and Slotemaker, but eventually moved away to win the class, an important victory.

DBE 71 was rebuilt, and passed through the hands of James Tangye and several others. In the 1980s, this car was bought by one Stirling Moss, by which time it had been fitted with a Hart 420 engine, and was used in the Piper Sports Car Series by Moss. More recently it was purchased by John Ruston in the UK and was prepped by Gareth Burnett’s GB Race Engineering for the 2006 Le Mans Classic in July.

Chevrons at Le Mans

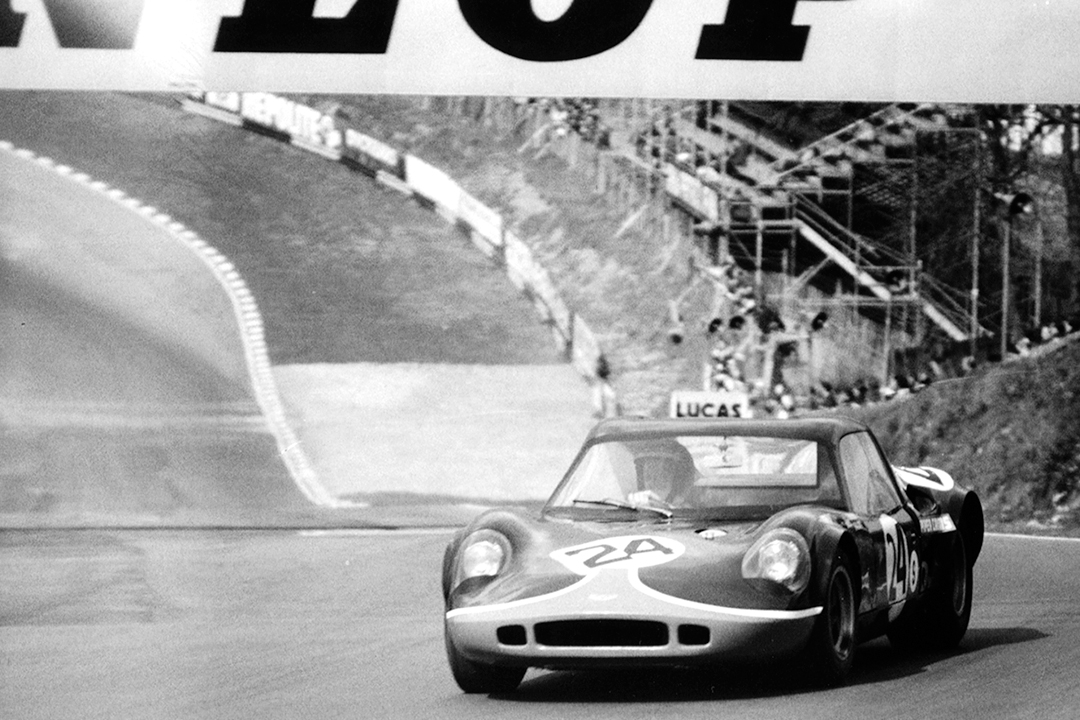

Chevron has never done particularly well at the Le Mans 24 Hours. Thirty-one cars took part in the endurance race of endurance races between 1968 and 1987. Only six made it to the finish, but five of those were class winners indicating their competitiveness against often very tough opposition. The first Chevron at the Sarthe was the unique B12, a B8 with a 3-liter Repco engine for John Woolfe and Digby Martland. It was quick but only lasted three hours. John Woolfe loved fast sports cars and would be killed on the opening lap of the 1969 race in the new Porsche 917. The first win went to the all-female team of Christine Beckers/Yvette Fontaine/Marie Laurent in a B23 in 1974. They were 17th overall but took the 2-liter class. In 1977, the French crew of Pignard/Dufrene/Henry in their B36 were 1st in class, 1st on Index of Performance and 1st in Group 6. The only B8 ran in 1969 when the JCB-supported Brown/Enever car lasted for eight hours. That car would turn out to be our opposition in 2006! Chevrons at Le Mans included the B8, the B12, the B16, the B19, a pair of B21s and several B23s and B36s, as well as the 3.3-liter Cosworth-powered B62 in 1985.

2006 Le Mans Classic

Though I had managed to do some important long distance races in the 1970s at the Nürburgring, Spa and the Osterreichring and several other 24 Hour events, I had never managed to include the great Le Mans race. I saw it as a spectator and then journalist in 1968, 1977, 1984 and a few years ago when Bentley was returning to glory. Earlier in the year, I mentioned to John and Gareth that I would respond very well to being added to their team to do some laps at Le Mans. This would be the ultimate track test!

The amazing thing about the Le Mans Classic is that it manages to happen! Nearly a thousand drivers are involved, and most of them were chauffeured in a variety of vintage buses, military trucks and other odd vehicles through the huge car club display to the biggest drivers’ briefing I’ve ever seen. That was on Saturday afternoon following the two long practice sessions from three on Friday afternoon until eight at night, and from ten until two in the morning. The challenge of getting a 37-year-old racecar through two practice sessions and three races in a short period is daunting enough, but our team was also seriously involved in driving in two other grids, with Gareth keeping an eye on other cars as well. We were hoping that carrying team number “1” was a good omen, but the first blow came in practice for the prewar cars when Gareth pitted early with Talbot BGH 23. It turned out that there was something distinctly foreign in the fuel and that had done its damage, and Team 1 was down to four cars as Gareth swapped to BGH 21 in Team 5. Several other teams reported similar fuel problems.

Luke and Gareth did the bulk of the Friday daylight practice, the aim being to get into a reasonable grid spot without overtaxing the car, which Gareth did with a cracking 4:46.995, though there was a stop to sort out a fuel pump problem. He had also lined himself up near the front of the prewar grid in BGH 21 and was 3rd in “Chocolate Drop” in Grid 6. All the grids had a daylight practice, and at 10 PM it was time for proper nighttime driving. Gareth was at 5:16 in the dark. At 1:30 AM, with thirty minutes to go, it was time for my Le Mans debut. As qualifying times were set earlier, this session was relaxed and I was just there to learn the car and the circuit. I had only sat in the Chevron during scrutineering, finding my way around and remembering where things were, a good thing as it turned out, as my next look would be in the dark. Behind the Chevron steering wheel sits the rev counter reading to 10,000 rpm, and I located the water temperature and oil pressure gauges to the left and the oil temperature gauge to the right, with the wiper, washer and flasher buttons. The rain light, key and starter are on the left with other lights, as well as voltmeter and fuel gauge. A large extinguisher sits in the “passenger” area. It was important to be able to reach the light controls and direction signals without hunting for them, given the speed differentials at Le Mans.

Driving DBE 71

Gareth flew into the now-dark pit-lane, having encountered a few laps of light rain, which quickly dried. As I was belted in, Gareth said one of the megaphone exhausts had fallen off at the Porsche Curves, “So don’t run over it!” (It was later found!) Knowing the engine might not be so crisp and there might be some fumes, I headed out into the rarified atmosphere of a Le Mans night. The Chevron caught the rumbling Ciaurriz Bizzarrini on the fast right-hander that now leads to a chicane on the way to the Dunlop Bridge and neatly outbraked it and pulled away quickly in pursuit of the Guerin Ferrari Dino and Kato’s Alpine A210. The track rushes down to what were the old Esses and then speeds up out to Tertre Rouge, now a very fast right-hand bend onto the Mulsanne, barely recognizable as the corner it once was.

As I went up from third to fourth to fifth, lights flashed in the rearview mirror, some way back. The yellow ex-Bonnier Lola T70 pulled alongside, joined by the Richard Meins T70 and, wait for it, the Luco/Guinand Porsche 917 in Gulf colors! This 28-cylinder trio didn’t leave the little 4-cylinder Chevron as quickly as I expected, as we all flew down toward the first chicane. Can you imagine it…it was the early ’70s all over again! Watch the nighttime sequence in Steve McQueen’s Le Mans if you want to get the slightest hint of this experience. I grasped the wheel tighter to stay focused. I realized that I had to chase this lot to see which way the corner went, and indeed the B8 pulled closer to the Meins Lola as the brakes went on. Aside from a little effort to find first gear in the pit-lane, I wasn’t even thinking about the car now, just about hanging on and not making a mistake in this exalted company. It was clear why the B8 often embarrassed bigger cars. I did, however, discover a Le Mans oddity on the Mulsanne. When you look in the mirror quickly, it’s not easy to distinguish between headlights and the tall lamps on this famous straight. I stopped looking as you could hear the big stuff coming!

The B8 was beautiful through the right-left-right of the first chicane and left-right-left of the second, and could hang onto the big bangers at the exit and then began to pull them in again at Mulsanne Corner. This used to be a tight right-hander, but it’s fast in third or fourth now. I stood here for hours in the wet and dark in 1968 on the signaling team for Mike Salmon’s GT40. I was now going through it faster than he did! I caught another Alpine and a black Mustang on the very rapid run up to Indianapolis, where there is a very late dab on the brakes before the complex that leads to Arnage…It was amazing just to know where you were on this historic circuit! There’s a top-gear blast past Maison Blanche, and then the Porsche Curves where I was slow in the dark as it was hard to find the line. In a few seconds, I had that strange sensation of going past the awesome pits and grandstand all alone…heading for another lap. What an experience.

What a way to go to Le Mans! I will leave the last few words to Gareth:

“The first time I drove a B8 Chevron had been on an icy cold test day at Snetterton in February—the wind chill factor was –3°! Even with this, I was impressed how easy a car the B8 is to drive—a very responsive and predictable chassis that immediately makes the driver feel in control—no wonder they have been so popular!

“Our first major race with the car was the Le Mans Classic 2006—what an introduction. Racing on Avon Slicks this little B8 was simply awesome. With gearing limiting us to 8,000 rpm, the little car was extremely quick. We had done limited testing and the car was suffering from front-end lift at high speed. This meant negotiating the kinks on the flat run down to Indianapolis required precision and balls, especially when passing a Ferrari Daytona on the outside! But through the Porsche curves the B8 was in its element, fast, precise and beautifully balanced. In the last race from Grid 5 the B8 started back in 26th place (as a result of a loose plug lead in previous race) and finished 4th overall—not bad in 45 minutes and a testament to its speed.

“For subsequent races at Nürburgring and Spa, we were able to undertake some more testing and development work—with the result that it was simply the quickest B8. At Nürburgring in the wet qualifying, she was on the front row of World Sportcar Master Race—splitting the Lola T70s, ahead of the B16s and 4 seconds quicker than the other B8s—including the fuel-injected car of Michael Schryver.”

“Simply a little jewel of a racing car!”

The Race

After Gareth had managed a good 2nd in the prewar Talbot, it was time for Grid 5’s first race. The first grid had started at the traditional 4:00 PM so it was now 10:20 PM. After something of a problem with a door flying open and needing to be taped, Gareth handed over to Luke in the first race and they pulled the B8 from its 14th position at the start to 11th and 8th on Index of Performance after the first 45-minute race. This had been won by Minassian’s Ligier-Cosworth, with a Chevron B16 3rd, the JCB B8 5th, another B16 just ahead of us in 10th. Behind our little green Chevron there was a horde of Porsches, Ferraris, Fords and other Chevrons. Looking good.

Our team effort had suffered two more blows as the Hugenholtz GT40 had suffered a fire in the Grid 4 race and was out, and worse still, Gareth Burnett’s Chevron B26 was rammed by Alain Serpaggi’s Renault-Alpine A443 while in 3rd spot and looking very competitive. The suspension was broken so that was that. In the B8, the second race started at 6:00 AM and was running well after starting 11th. Gareth came in for the mandatory stop and Luke took over, but the battery was flat and needed to be changed. This dropped the car to 38th but we managed to bring it back to 26th by the end of the 45 minutes. After the first two races, we were 18th overall and 13th on Index. The second race had been won by Bill Murray’s ex-Gulf GT40 on Index but the overall leader was Minassian in the Ligier JS3.

The team decision was that Gareth would do all the driving in the final race, starting at 2:00 PM on a bright warm Sunday afternoon. From 24th, Gareth started the charge with Jo Bamford in the JCB Chevron alongside. The two B8s carved through Danny Sullivan’s Ferrari 365GTB4, Mayston-Taylor’s GT40, Guillot’s B16, Yves Junne’s Porsche 906, Escande’s LolaT212, another 906, Quiniou’s B16, and the Hottinger B8. By the end of lap one, we were in 14th while Minassian led in the Ligier. Rain started to fall but Gareth was in 12th the next lap. During the pit stops, the JCB B8 managed to get to 6th but our green car soon caught and passed him, going past Rosina’s Lola T70, the Alpine A220 and the Stretton/Hinderer T70. As the flag came down, the green Chevron B8 was in a fantastic 4th spot behind the winning Porsche 917, Thuner’s T70 which had started just behind us, and the Ligier. With 4th on Index in that race, we finished 6th in the general classification and 8th in Index of Performance. That left the JCB B8 one place ahead of us. What a way to go to Le Mans!

Specifications

Chassis: Tubular space-frame

Engine: BMW straight 4

Location: Midengine, longitudinally mounted

Capacity: 1990 cc. (121 cubic inches)

Valve train: 2 valves per cylinder, SOHC

Fuel system: 2 Weber 48 DCOE carburetors

Gearbox: 5-speed manual

Drive: Rear-wheel drive

Power: 240 bhp

BHP/liter: 121 bhp/liter

Resources

Many, many thanks to John Ruston, Gareth Burnett, Luke Stevens, Neal Bailey and the GB team.

Gordon, D. Chevron—The Derek Bennett Story. DBG Publishing 1991. Stockport, UK.