There are cars, and there are cars. Some come and stay, many come and pass on. A few appear briefly but don’t make it to the grid, and then they disappear. Thanks to historic racing and car collecting fever, however, a number have managed to rise from the ashes. VR has had the good fortune to get behind the wheel of some of these—the Amon, ATS, DeTomaso, Scirocco—all F1 cars that struggled in period and never made the grade even when so much effort went into them.

Historic racing brought them back, and not only did they experience the miracle of resurrection, they got significantly developed, and in historic events over the last few years they all fared better than they did in period. Well, this is the story of another of those “almost lost” cars, the six-wheeled March Grand Prix car, 2-4-0. This car never made it to a grid when it first appeared—and maybe it was never even intended to get onto an F1 grid—but it’s back in no uncertain terms, and again it shows what might have been.

The Six-Wheelers

When the Tyrrell P34 appeared in historic racing a few years back, virtually all the enthusiasts knew about it, largely because it had been on the scene for two seasons and it had won. But for any newcomer to racing, it was a pretty amazing concept. When the March 2-4-0 showed up on grids much more recently, it really took people by surprise, and many younger fans were heard to say that “there never had been a six-wheel racing car.” That, of course, is not true.

Six-wheelers go back to pre-war days. There were ERAs and Altas that sprouted pairs of twin rear wheels on a single axle, though these were almost all confined to hillclimb meetings. Then the Auto Union Bergrennwagen copied this approach, but whatever future it might have had ended with the onset of war. There had also been the fabulous streamlined Mercedes-Benz M80; though it would have been a record-breaking effort.

Much less well known was the American Pat Clancy Special in 1948, a Kurtis-Offy Indycar with two axles at the back. It was not very successful. It wasn’t until the mid-1970s, when Grand Prix design had reached a kind of dead end, that something new came along. The chassis, engines and tires used by most of the teams were very similar, often identical, and in-depth knowledge of aerodynamics was still somewhat limited. It took Derek Gardner, Ken Tyrrell’s designer, to find an advantage, especially in a car’s cornering capability. It was known that the large front wheels of a GP car tended to generate lift, which was being compensated for by the use of wide front noses.

Gardner worked out that he could decrease lift by reducing the front tire size, and make up for lost grip by having two sets of front wheels, all of which could also steer and improve braking. The racing world was pretty stunned when the P34 appeared at the end of 1975, and even more surprised when it won the Swedish Grand Prix in 1976 where it also scooped up 2nd place. The Tyrrell P34 had flaws; the brake balance took a lot of development, and the front suspension was heavy. The main limit on progress, however, was that Goodyear was less interested in developing the ten-inch front tires for the car, so it did not move forward, and at first did not seem to stir great enthusiasm among its rivals.

However, one thing the P34 did do was to inspire the manufacturers of model cars to produce thousands of examples of the six-wheeler, and that was of great interest to sponsors—and to one Max Mosley at March. We will come back to that shortly.

During the 1976-’77 period, in addition to the March project, there were rumors circulating that BRM was going to produce a six-wheeler with four wheels at the rear, and that Jean-Pierre Jarier had been asked to drive it. It never happened. Then in early 1977, there was the report of a test of a new Ferrari, the 312T6, with four small wheels sharing a single axle at the rear. Carlos Reutemann tested it and frightened the life out of himself. He managed to crash it under the nose of the Commendatore himself, and it burst into flames! It was rebuilt, but Reutemann did not want to drive it. Then in the early 1980s, Frank Williams came up with two variations on the theme, an FW07 and then an FW08 with four rear wheels, each pair on a separate axle. There was even a rumor that the Lion GP car would appear with 12(!) wheels, all driven! But then four-wheel drive and anything with more than four wheels was banned, and that was that. By this time, however, ground-effects and other technical advances were outpacing the possibilities these earlier creations seemed to promise.

Photo: Mike Jiggle

March on Six Wheels

On reflection, I think it is probably safe to say that March never had any intention of producing a serious six-wheel Grand Prix car.

March was formed in 1969, running an F3 car that year but promising to produce a broad range of cars the following year, including an F1 car. The company, led by Max Mosley and Robin Herd, had lots of potential. They sold cars to Ken Tyrrell for Jackie Stewart, and had some great drivers on board—Chris Amon, Ronnie Peterson, Mario Andretti and others. They produced good results, but got carried away with enthusiasm and the desire to build and sell everything, and they just couldn’t do it all. The team looked good for 1972 with Peterson, but the Herd-designed 721X was a failure and they were only just managing to survive, building up F2 chassis to F1 specs to keep going. The efforts and money of Hans Stuck Jr., Vittorio Brambilla and Lella Lombardi kept the F1 team going into 1975.

The 1976 761 was essentially a modified 751 of the previous year; in fact, many 761s used original 751 chassis. Ronnie Peterson won the Italian Grand Prix at the end of the season, but that was the only time a works March got onto the podium that year. The future was not looking bright, and the 1977 effort was going to be another update of a three-year-old car. Where the notion of a six-wheeler came from is not entirely clear. Certainly Robin Herd had a close look at the Tyrrell P34, but saw it as a “dead-end” and did some thinking about the whole car’s frontal area, realizing that the big rear tires created most of the drag problem. He reasoned that four front wheels at the rear would reduce the overall frontal area and could allow the use of four-wheel drive for better traction.

Photo: Ferret Fotographic

It was around this time that Max Moseley noticed just how well models of the P34 Tyrrell were selling in the run up to Christmas, and he thought this would be a fine inducement for a much needed new sponsor, which March was desperately searching for. Thus, he supported Herd’s plan. It was a very low budget project, basically no budget at all. In true March tradition, however, the team thought if they could find the money, they could run for another year and work out the details when the time came. As a result, mechanic Wayne Eckersley was locked in a room with Brambilla’s 761 chassis and told to make the design work without spending any money. The rest of the team didn’t know what was going on in that room and were under threat of being fired if they entered! Eckersley had access to all the existing March parts, but the key ingredient would be the transmission, specifically the gearbox casing, which would have to handle the additional stress of two more wheels. Effectively, the nicely designed and strengthened casing was too expensive, so it was replaced with a much cheaper one. This single move created the “Achilles heel” that would scupper the project.

The launch was “Sex, Lies and Videotape” without the Sex and Videotape!

Today’s F1 technology is so complex that very few ordinary mortals can comprehend it. Thus, the Adrian Neweys of Grand Prix racing don’t spend a lot of time even trying to explain concepts to journalists, never mind the public. It was simpler in the 1970s. You had to have skill in pulling the wool over people’s eyes. March had a team that was good at this.

Photo: Ferret Fotographic

When Vintage Racecar gathered at Sywell Aerodrome to conduct our test, we were joined by some very interesting people. Tony “Taff” Smith owns the car, and he brought it along to Patrick Morgan’s Dawn Treader Performance workshop where much of the technical work had been done to solve the problem of the gearbox casing and its internals. Also on hand was Martin Walters who worked in March’s design team, and at the press launch on November 24, 1976, was named as the designer. Martin explained to us some of the complexities and nuances involved in working at March in that period! During our test day, Dick Scammell, mainly known for his long-term involvement with Team Lotus, also showed up as he was doing some work nearby. It was an intriguing day, full of history and mystery.

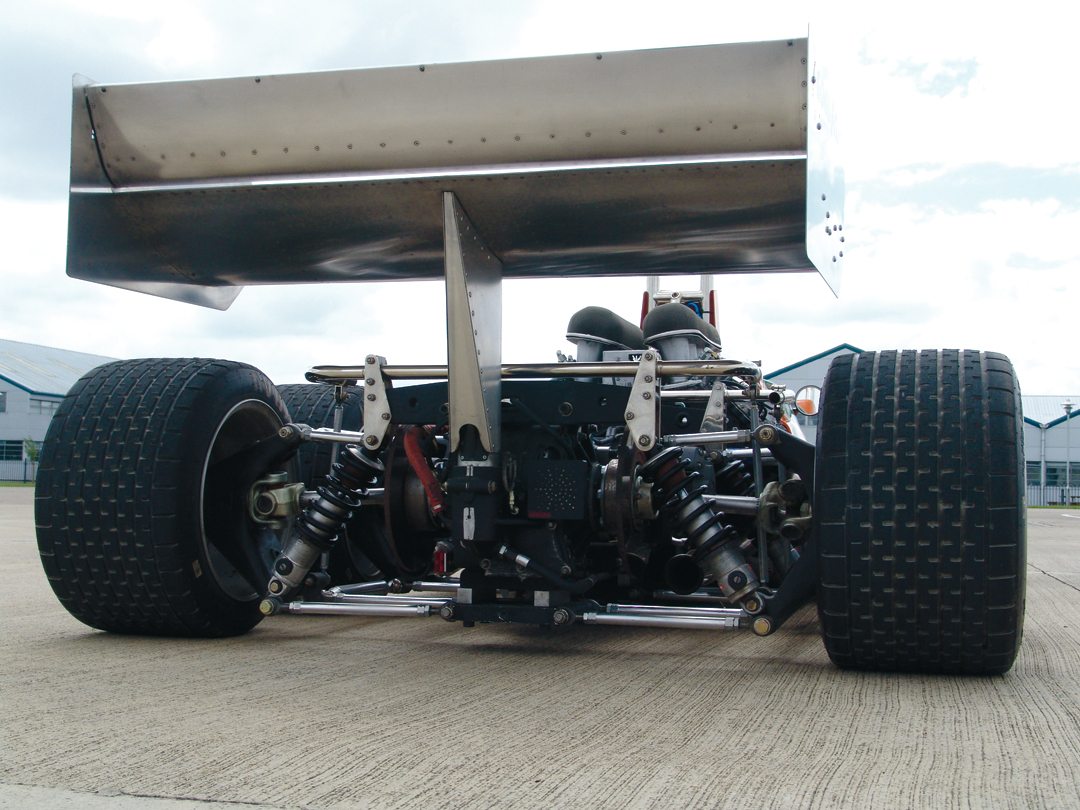

Of course, the key ideas for the car had come from Robin Herd, but BMW was critical of March for spending too much time on F1, rather than their successful F2 team. Thus Martin Walters got the credit, or the blame, for the new project. At the launch, the car appeared with the complete looking rear end—each pair of rear wheels had inboard-mounted brakes, and outboard coil-spring damper units with two sets of lower parallel links from the modified (F3) upright. The gearbox casing was, however, empty and the engine was a dummy.

The car was announced as the 2-4-0, which is railway-speak for two leading wheels, four driving wheels and no trailing wheels. Martin Walters was uncomfortable in the role of spokesman, and he was faced with a very suspicious group of journalists who said, accurately, that they were looking at nothing more than a full-scale model of a car. Mosley started the discussion on the car’s potential, while Herd referred to “full-scale wind tunnel testing” that had never happened—all evasion tactics! Under pressure Mosley announced that full testing was to commence within two weeks. The March team was set to work building a “real” car from Stuck’s 761/2, with Brambilla’s orange livery but a nose from the Doug Shierson Racing Formula 5000 76A.

In the third week of December, the car went to Silverstone for testing. Jody Scheckter’s brother Ian had just been signed for the F1 team and he was going to do the early testing as part of an effort to bring his sponsor to the project. He was busy on the day, so “test driver” Howden Ganley got the job as Scheckter really didn’t want to do it. The cheaper version gearbox casing—now with internals—couldn’t take the strain and broke on the first lap. The details of the second test are sketchy (I’m waiting for Howden’s autobiography for the real story) and there were contradictory reports about how much running it did. It seems likely that it did some twenty miles on part of the circuit rather than full laps, but Ganley was said to be impressed with the traction. However, it does appear that it was running with only one set of wheels driving at the rear!

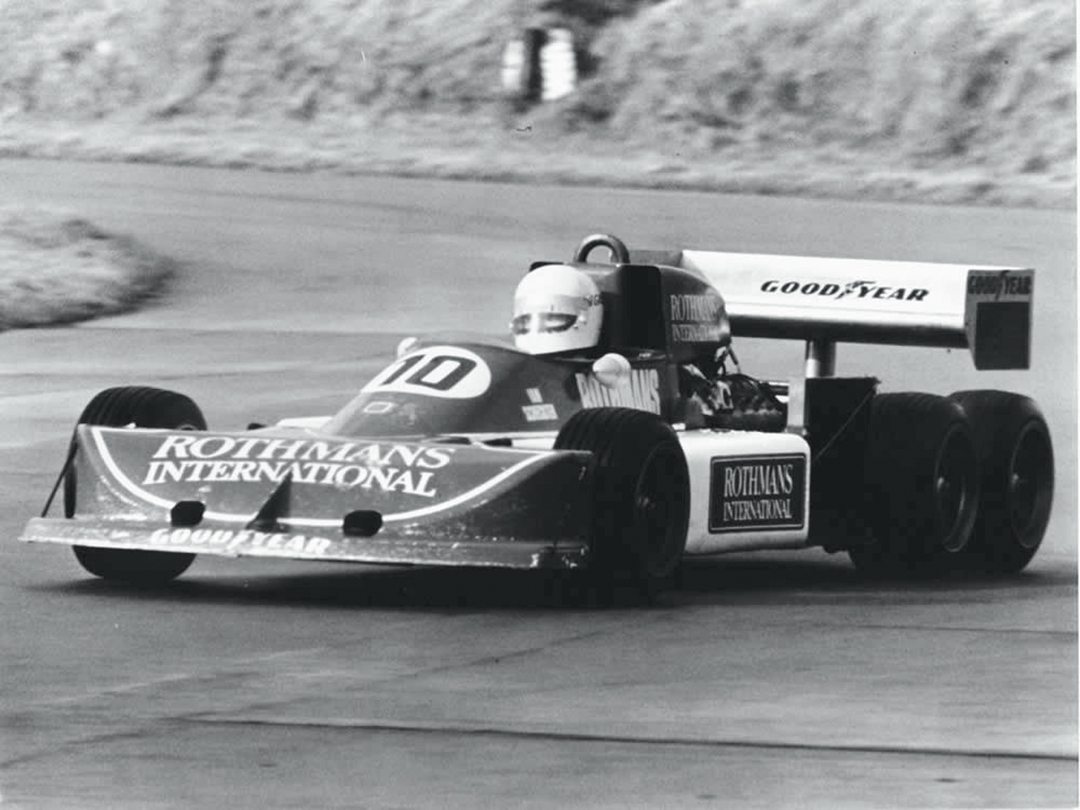

Photo: Keith Long

There then seems to have been a further test at Silverstone or Goodwood in which the casing issues had been resolved and all four wheels were driving the machine. Ian Scheckter did a short test at Silverstone in February, and this occurred after Mosley’s efforts to bring Rothmans sponsorship on board had been successful, though indeed this would all go toward a “conventional” F1 effort. One of Howden’s tests seemed to indicate some serious potential, but a development and weight loss program never happened and the car was put aside, though the idea that it would run was left ringing in many people’s ears. March then struggled on through 1977 and left Formula One. It was tragic that the funding was not there to develop the car for 1977 as it had great traction, brakes and the smallest frontal area of any car in the field.

Ironically, March built up a new show version of the car after the chassis had reverted to regular 761 use, and the Scalectrix company handed over a large amount of money for use of this show car and the model that sold in huge numbers. The car was also used by Goodyear for shows for a few years before disappearing to be locked away.

2-4-0 Goes Climbing

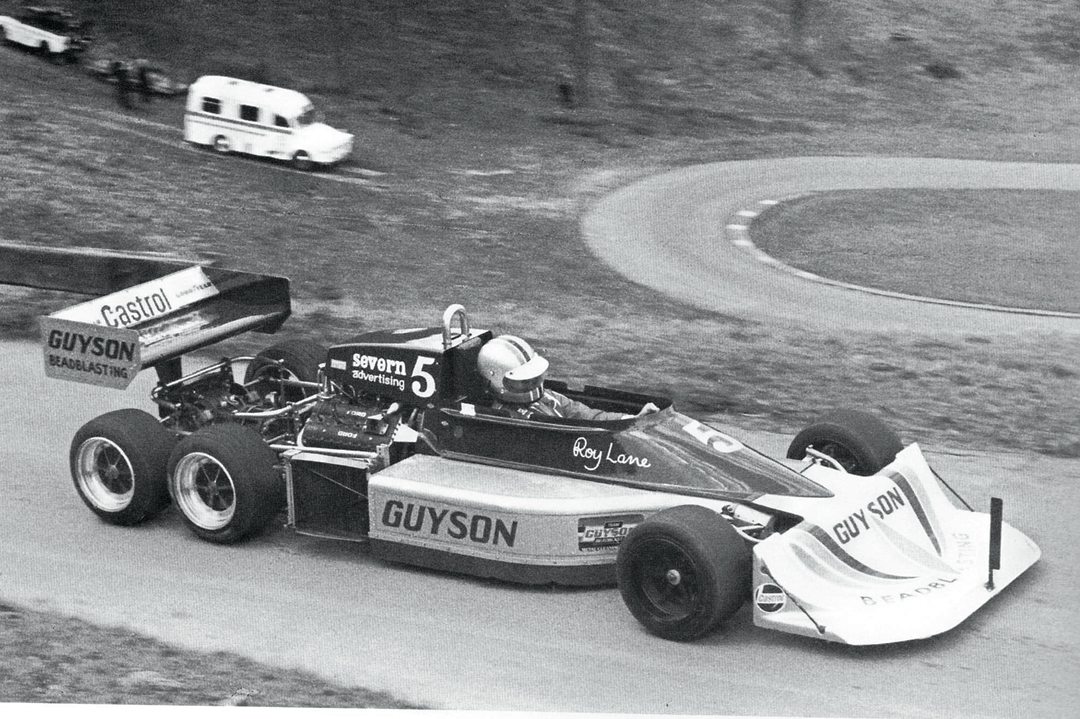

Roy Lane was one of the best known of British hillclimbers, winning the championship four times in the 30 years that he contested it, with 90 victories to his credit. He was the period master of the big engine on the very tight and twisty British hills, and won the title in 1975 and 1976 with an F5000 McRae. In 1977, he campaigned a 1974 March that only started to run well halfway through the season and then went very quickly indeed. He ran that car in 1978 and went to Robin Herd to try and buy Ian Scheckter’s 1977 771. Of course, the original 2-4-0 had been converted back to normal specs, but the rear four-wheel setup was still in the workshops. This was fitted to the 771 chassis and engineer Lane set out to make the system work, as it looked to have great hillclimb potential.

At the first meeting at Wiscombe in Devon, it was a rainy April day and the car was quick in the wet, though his competitors got faster as the hill dried. Lane still managed to win the run-off at the end of the day by nearly a second. It rained again at Prescott and the car won again. At Loton Park, it was dry and Lane still managed to win in the racing car class. In the final run-offs, however, the gearbox broke in half, and though he repaired it for his second run, it failed again. There was another failure at Doune in Scotland, so serious modifications were made to the lubrication system, which had, in fact, been pushing oil away from the gears. The car ran well at Prescott, managing 2nd, and then was 5th at Harewood with a steering problem. He seemed to have the Barbon Manor event tied up in the wet, but was beaten at the last minute by an F2 March 782. Then he couldn’t get into the top ten at Shelsley Walsh, so for the Fintray hill the 2-4-0 rear end was removed and the car returned to four-wheel spec. His problems, however, did not disappear and he finished 5th in the championship, but at least 2-4-0 had given a glimpse of what it was capable.

Resurrection

Lane sold the car—the 771 chassis—to Martin Johnson in 1980, and in 1983 it went to Alan Ratcliffe via John Brannigan, and a few years later Ratcliffe also bought the 4WD system from Lane and had Graham Eccles build it up as a show car. In the early 1990s, the chassis and 4WD were separated, as the chassis was sold by Eccles who then died, so Ratcliffe only had the 6-wheeler components. Then a Liverpool haulier bought a trailer of racecar parts that included the 6-wheeler bits, which were sold in a complex process to Richard Parkin who put together a collection of all the parts for 2-4-0 including tub, bodywork and uprights. This was then purchased by Tony Smith in 2009. It is important to note that whereas it is usually the chassis that retains a racecar’s identity, in this case it is the unique 2-4-0 transmission, which over time was attached to several chassis but is what gives the March its identity. This is unique, though there is another 2-4-0, the show car with a “Mark 1” transmission used in the December 1976 test at Silverstone, and that one is in Holland.

Tony Smith had seen the car sitting in a barn two years before he bought it and it just stuck in his mind. He had run an F2 March 782 and an F1 Surtees TS20, but is a relative newcomer to racecar building. He recognized the remains of 2-4-0 when he saw it with the transmission, the uprights and radius rods all bolted together and rusted solid, sitting as it was when removed from Roy Lane’s 771. Tony sold the Surtees to begin work on this daunting project, most of which he has done himself. The Surtees money went into an engine and getting the gearbox sorted, but building a tub and getting it together took two years. Smith was fully aware of the issues with the car, and had a chance to talk to Roy Lane about it not long before Lane died in 2009.

“Roy raved about it, about the steering and how well it performed and said ‘go for it,’ and I took his advice. I’m glad I did. March had never developed it, so it never really ran on a circuit, and when we started doing ten or twenty laps, things started to appear. One was the connection of the pinion shafts, which had to be modified, and we were running out of lubrication on the bearings where the halfshafts come out of the side plates. This is where I went to Patrick Morgan for help. When I’m in trouble I lean on Patrick!”

Patrick Morgan gives most of the credit for the car’s successful reappearance to Tony and his son Jeremy who drives it, but Dawn Treader played a key role in sorting the sticky problems:

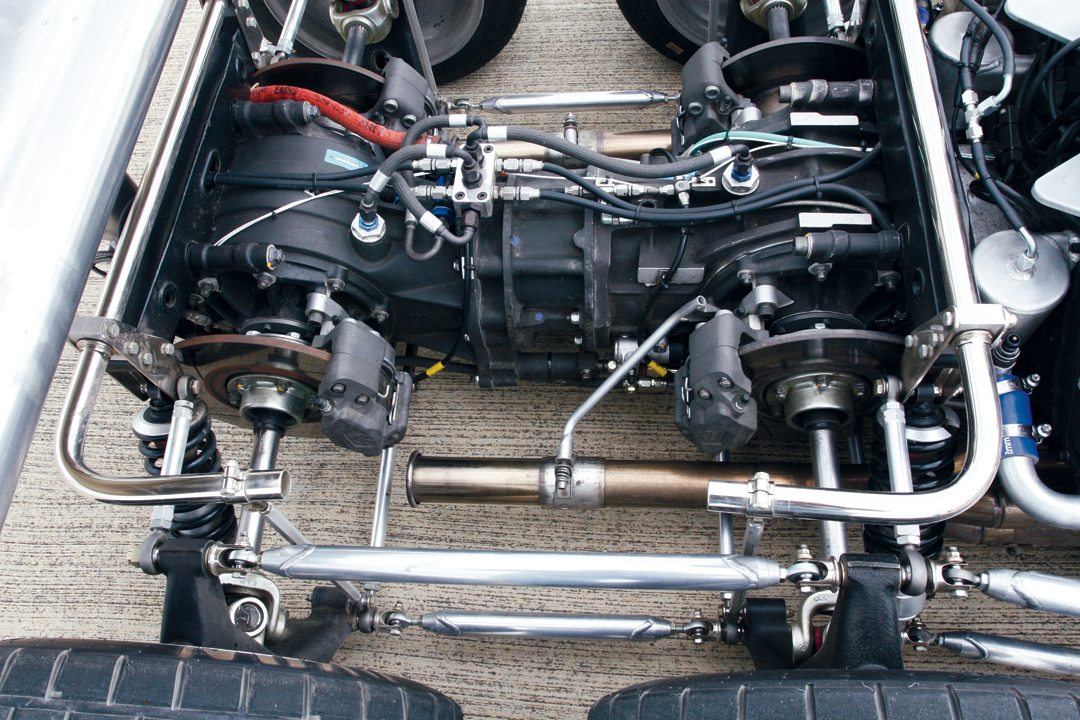

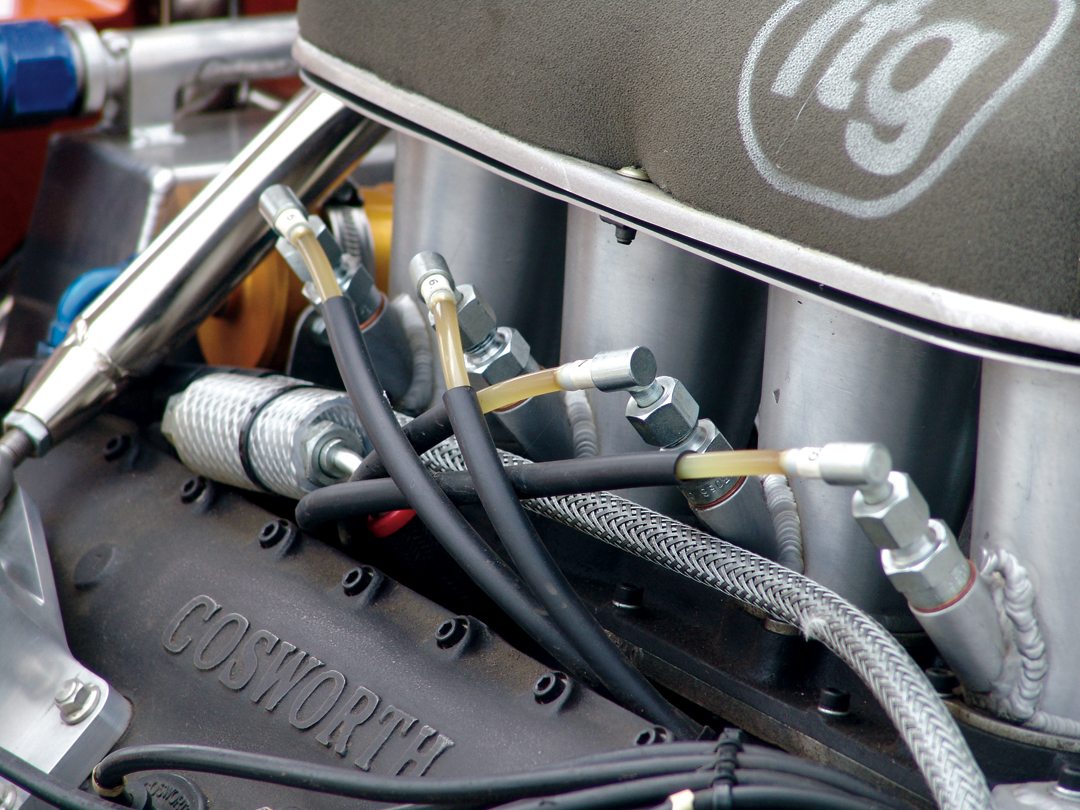

“Basically it was down to the oiling system of the gearbox where there were several issues, probably the most important of which was the oil that was used in it which was a thick, sticky oil based on the belief that this oil would stick to the gears rather than being flung around the gearbox, which made it very difficult to get it into the outer bearings, which failed. The other issue was that at some point the rear squirt jet that oils the crown wheel and pinion had been made into a cap with a hole in it and the orientation of the hole would be completely dependent on the thickness of the washer used to seal it to the top of the casing, and it turned out to be pointing away from the crown wheel and pinion and was squirting into space!”

There was also a problem with the two-sump configuration where if the rear started drawing air, the front had no chance of sucking oil through to the front, so Dawn Treader moved the oil pipe down into the sump. That is a brief summary of the significant work that was done to enable Jeremy Smith to begin to look so impressive with the car. He was 8th in the run-off at the Goodwood Festival of Speed, the work having inspired confidence that 2-4-0 could now be a success on hills and on circuits, where it is looking equally promising.

Driving 2-4-0

Look at the photographs. From the front, 2-4-0 looks like a conventional March F1 car, though without huge rear tires. In fact, it is difficult in some front-on shots even to see there are two pairs of wheels at the rear. The side view, however, is extraordinary. The car looks very long, and I have to admit I thought that would be evident in the driving. Wrong!

Because Jeremy Smith is 6’2”, the cockpit suits him, so some padding was stuffed in for me. It was then quite comfortable, though snug and tight around the shoulders, but much what you would suspect—and want. Pedal access was easy, and everything is within easy reach. The interior is 1970s except for more modern electronic gauges and early-style Momo steering wheel. The gearshift lever is to the right, and I really expected some surprises from this department, and was prepared to treat the transmission very gingerly. Wrong again!

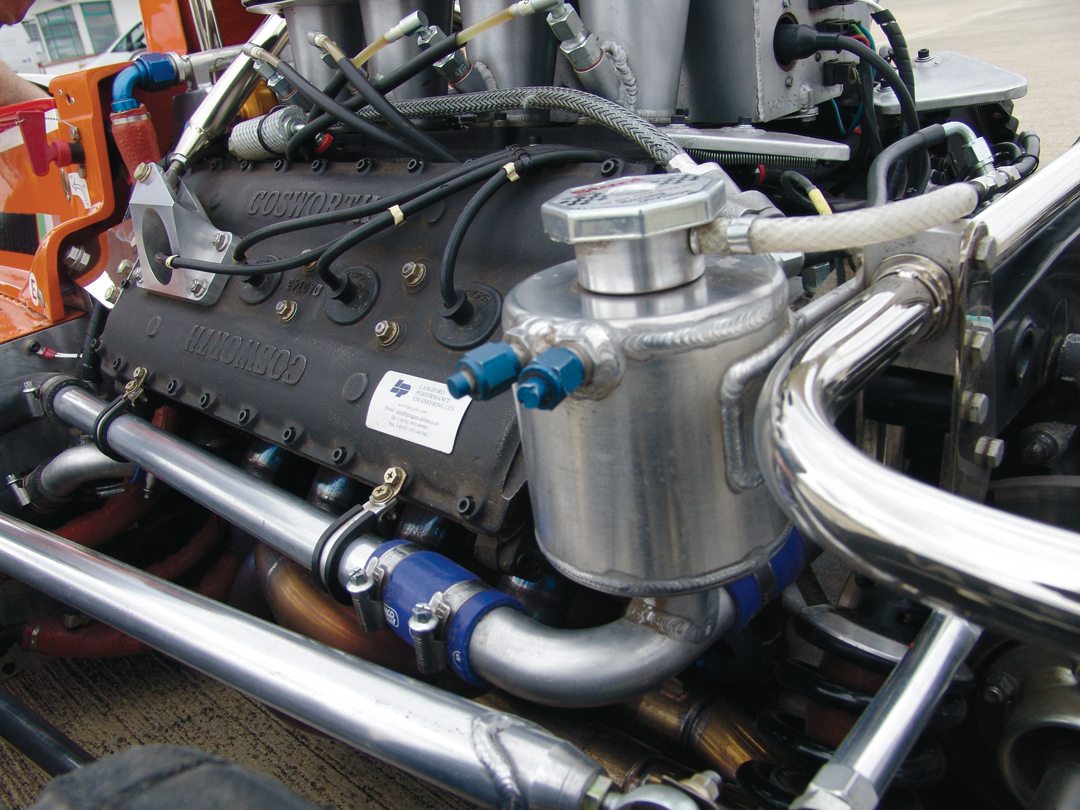

The Cosworth engine uses some 10,000 rpm in competition, and we would be deploying probably 7000 for our test. All the quirks I was anticipating from this historically odd machine failed to appear. It was off the line at 3000 rpm with no trouble, and the 5-speed box was totally indistinguishable from any other F1 car of the period. Now this was a test on an airfield runway, so would it be possible to find out what the novel features were? It happened to be on wet tires—appropriate considering its wet-weather history—and it was a dry day. Acceleration was crisp, braking was impressive as the six brakes warmed up quickly, and there was not the slightest indication that the car had a unique rear end—on the straight.

So, I decided to see what it was like to do a series of turns in each gear, searching for clues to what the traction was like. This was a revelation. Come out of a slow 180-degree turn in first and accelerate, and it was quick as you would expect. It was the same in second gear, and in third, and fourth, and fifth! The transmission was superb at getting the power to the ground. It was even more dramatic at higher speeds, going through a medium speed bend in third, and then trying it faster in fourth and then in top. 2-4-0 sticks and sticks, and now that its Achilles heel has been smoothed and sorted, that magical back end does what it always was potentially capable of doing. It’s hard to know whether Robin Herd believed it could, or ever would, be this good. Tony Smith is adamant that Robin Herd was serious about the car, and Herd was recently quoted in Racecar Engineering, “It would have worked had we been given the money to do so, but we just knocked it together. We were always compromising on money. It would have needed some effort to knock some weight off the six-wheel car. Roy Lane proved its worth in hillclimbs.”

The Smith boys have also proved its worth. No wonder they struggle to get near their own car at race meetings. The crowds are thronging to see what might have been—and now is.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis: Aluminum monocoque

Engine: Cosworth DFV

Capacity: 2993 cc. V8, 466 bhp

Brakes: 6 inboard mounted discs

Suspension: Outboard coil-spring dampers with two sets of lower parallelinks; “normal” arrangement of upper/lower radius arms links; “normal” arrangement of upper/lower radius arms

Transmission: Drive is 4WD at rear; two-differential system; two gearbox sumps with pump at rear; front casing is standard Hewland-type casing; special spec rear casing, the two coupled together

Wheels & Tires: Avon 10.0/20.0 x 13 all around

Acknowledgements / Resources

A big thanks to Tony Smith for the freedom to enjoy his car, to Patrick Morgan and Dawn Treader’s Mark and Kris for making it possible, to Mike Bletsoe-Brown for letting us have Sywell Aerodrome for the day, and to Martin Walters for being the historical authority on the spot, and Dick Scammell for his usual enthusiasm for racecars.

Brown, A. Dossier – March 2-4-0 OldRacingCars.com

Lawrence, M. The Story of March…Four Guys and a Telephone Aston Publications UK 1989.