1969 Lola T70 Mk3B

Forget, for a minute, the origins of the Lola GT, the Mk6, the connections with the GT40, the Spyder, the Lola-Aston, and the differences between an Mk3 and 3B. We’ll get to some of that shortly. First, let’s get down to basics. When I first arrived in the UK in 1968, it was some three days before the Brands Hatch Six Hour race, but this major change in my life didn’t afford me the opportunity to rush off to that race. Likewise, I missed the Oulton Park 1000 Miles, where the singleton Lola T70 Mk3, entered by Sid Taylor for Brian Redman, beat the assembled GT40s, Ferrari Dinos, and Porsches to win by nearly two minutes.

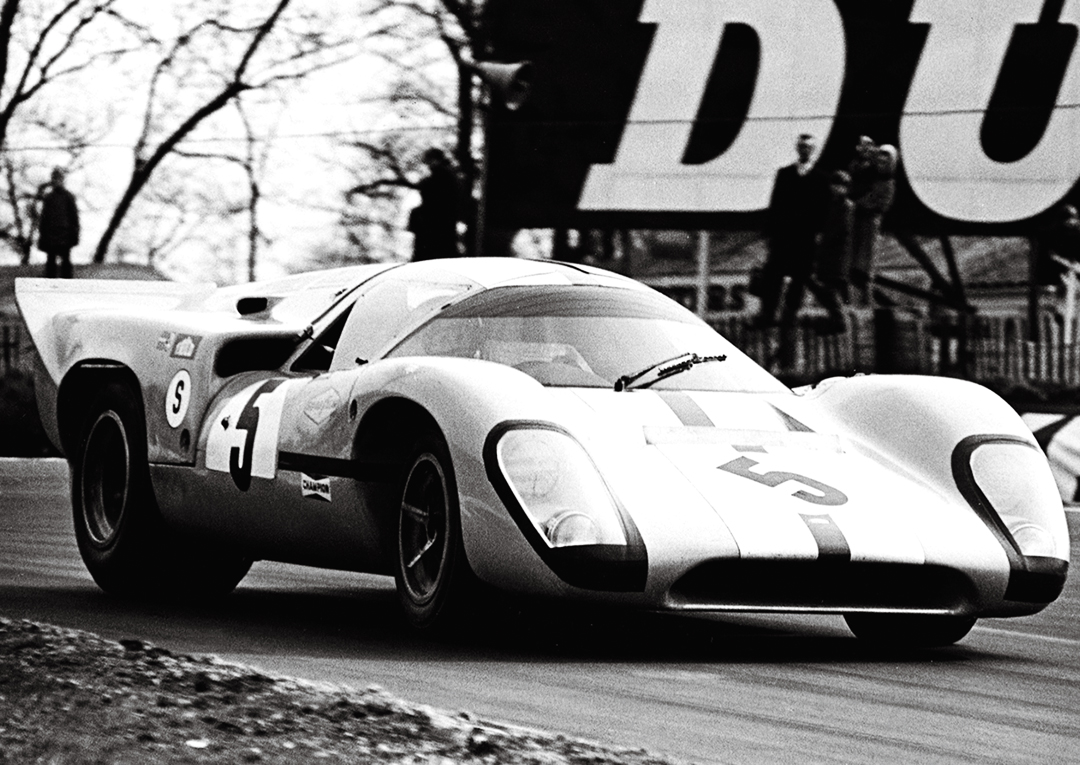

However, I was there at Silverstone on April 27 for the International Trophy race. The Players Trophy race of that weekend was the third round of the British Sports Car Championship where six GT40s, David Piper’s Ferrari 250LM, a horde of Lotus 47s, and Porsche 906s would be up against Denny Hulme in Sid Taylor’s white T70 Mk3 and the colorful Jo Bonnier T70, resplendent in yellow with red and white stripes. I parked myself on the outside of Copse Corner at the end of the pit straight for my first experience of the Lola T70, powered by big Chevrolet engines. This was to be a 20-lap sprint, so it was flat out from the drop of the flag.

The GT40s looked quick, as a massive wall of sound and dust hurtled into the first corner, but a minute and a half later, Hulme and Bonnier came past, already opening up a small gap on Paul Hawkins’s GT40. Just over 30 minutes later, Hulme led Bonnier over the line by three hundredths of a second, 20 seconds ahead of Hawkins. Bonnier set fastest lap, but the shrewd Hulme was in front when it mattered. The Lolas turned into Copse beautifully and the Chevy bellowed out of the corner up to Maggotts. From that point on, I was hooked on Lola.

Hulme repeated this performance in the Tourist Trophy in early June at Oulton Park, beating Hawkins to 2nd place this time, as Bonnier had retired with a split fuel tank. Hulme paced himself to win by six seconds, but a few weeks later Aussie Frank Gardner took over Sid Taylor’s pristine machine from Hulme and he, in turn, beat Hawkins, who at least managed 2nd this time. This was the Guards race at Mallory Park and Mike De Udy in another T70 Mk3 finished 3rd. Only four days later, I watched Hulme do a repeat at Silverstone when he won the Martini Trophy race, and once again the GT40 of Hawkins was the runner-up. Bonnier and De Udy both dropped out, but this time Hulme’s margin was only 2 seconds, after 65 laps, with Hawkins well wound up. The Lola Mk3 was proving to be a sprint racer’s dream.

Back at Oulton Park in August, Hulme was away racing in F1, so Gardner was back but crashed the Taylor car in practice. This allowed De Udy and Bonnier to fight it out and De Udy won, with Hawkins—having given up and gotten himself a T70 Mk3 as well—finishing in 3rd!

The final round was at Brands Hatch on September 2, a beautiful sunny day at the Kent circuit, and I was on hand for another dose of thundering sports cars in the pre-3-liter prototype days. There were six T70 Mk3s there at Brands. Gardner was again in the Taylor car with the green stripe, and Swede Ulf Norinder was on the pace in his lovely light blue and yellow car. Hawkins was back in the GT40, and David Hobbs had the Jackie Epstein T70. David Prophet brought his new car. De Udy was there, and John Wolfe had deserted his Chevron-Repco for a superb T70 in dark blue and yellow. Gardner was the winner on the swooping Brands circuit, and the Lolas were spectacular as they barreled into the tight, uphill Druids Hairpin, went hard on the brakes, and then powered out down the other side. Norinder was on form in 2nd with a brilliant Peter Gethin putting a 2-liter Chevron B8 into 3rd after 50 laps.

The T70s had left a lasting impression on everyone who saw them. They were beautifully built, had an effective and shapely body, sounded great, and made such good use of that Chevy V-8 engine. I had another treat in store for me, when I went to Le Mans at the end of September. The race had been postponed that year after the political disturbances in June. It was a great introduction to the 24 Hour classic for me, and I have enduring memories of the win by Pedro Rodriguez and Lucien Bianchi in the JW GT40, the great result of the 2-liter Alfa T33s, and the thumping Chevy engines of the two T70s. The dark-blue car of Epstein/Nelson lasted until the 17th hour, while Norinder and Sten Axelsson went out after only a few hours. But they were stunning to watch and hear…and they were so sexy.

Whence the MK3B

The term “sports prototype” first emerged in the mid-1960s when it was clear that what had been GT cars and then GT prototypes were rapidly becoming pure, mid-engine racing cars, and indeed were not prototypes of anything. The quest for victory at Le Mans had revived interest in closed coupe designs with big American engines. Group 7 racing had become popular in Europe, with unlimited engine size, and when Lola’s Eric Broadley left the Ford GT40 project, he revived his own firm and produced the open Lola T70, a monocoque “spyder.” For purists, this car was always the T70, but the name spyder got attached to it and never left! The 1965 T70 was designed to accept any of the likely American V-8s, and looked likely to be a force in Group 7 competition.

John Surtees set up a team to run a semi-works car, using first a 4.5-liter Oldsmobile engine, then a 5-liter Chevy and, toward the end of the 1965 season, a 5.9-liter Chevy. John Mecom’s team in the USA was running two cars in the USRRC with 4.7 Ford units. Broadley then designed a lighter, sleeker, and stiffer monocoque for 1966. Surtees tested the new prototype, which won the first time out at Brands Hatch, but he then had his huge crash at Mosport, which took him out of racing for the rest of 1966. However, the new car was immensely successful in Group 7 events. This success prompted Broadley to start work on a coupe version for 1967, about the same time as Jim Hall was working on a Chaparral endurance coupe. Aston Martin supplied the first engines for Lola to test, with the aim of ultimately returning to Le Mans.

Photo: Peter Collins

Plans to homologate the T70 into Group 4 had not been finalized by Sebring 1967, when the new Mk3 T70 coupe first appeared in Group 6 configuration for Buck Fulp and Roger McCluskey, but it failed to start. As cars were being prepared for customers with various engines, including the 5.5-liter Ford, the Aston-Martin-powered machine (known as the T73, though more usually as the Lola-Aston) was readied for the Le Mans test days. The Mk3 was very much the work of Broadley, with assistance from Tony Southgate and others, the coupe body being an effective device attached to an improved Group 7 chassis. The body diverged from common thinking with a rear roofline that didn’t taper in the way that the contemporary Ferraris and Fords did. The T70 showed great promise in all its forms, with a variety of engines in 1967, but just couldn’t produce the results. In 1968, as I mentioned at the beginning, this started to change dramatically. While endurance racing victory still eluded Lola, the car had become immensely effective in shorter races, especially in Britain.

However, it had been announced in early 1968 that Group 4 regulations were being revised for 1969. This meant that only 25 rather than 50 cars needed to be built for Group 4 homologation. On paper, Lola appeared to be the fastest contender for 1969, but of course, the existence of the Porsche 917 was still a well-kept secret.

Broadley’s contender for 1969 was the Mk3B. This caused some confusion when it was first announced and when it appeared. It had nothing to do with the 1967 Can-Am racer, which was a Mk3B “spyder” and was sold in 1968 as a customer car. John Surtees had played a major role in revising the Can-Am car and helped develop the T160 into the T162, which became the basis of the Mk3B coupe. The new coupe bore a strong exterior resemblance to the earlier car, but was in fact much different. Really it was a new car. The monocoque was now all aluminum with the exception of two magnesium cross-members in the roll hoop. A great deal of effort had gone into saving weight, attempting to get down to the minimum allowable 800 kilos. Fuel was to be carried only in a left-hand pod as a means of balancing the driver’s weight. The car featured a Hewland 5-speed gearbox, but the crown wheel and pinion had been redesigned after numerous failures. The front suspension uprights had also undergone a re-design to improve better airflow to the brakes and to allow a wider range of wheel sizes. The rims were now 15 inches wide, though 13-inch wheels could be fitted to the rear depending on the circuit. Much stiffer springs were being used, and in general, a number of ideas were now following contemporary F1 trends.

When the Roger Penske-run Mk3B coupe won at Daytona, in February 1969, the future looked rosy. But, then, the 917 appeared on the scene and the Lola, with all its new features, looked like old technology in the face of the Zuffenhausen product. Though it struggled in endurance events, Jo Bonnier did manage a 2nd place with Herbie Muller at the Osterreichring that year. However, the Lola’s superb handling was a source of great envy for Porsche—it was wonderful on high-speed circuits and the drivers loved it. It remained a major player in national sports car races for the season, and at Le Mans it had been timed at a hair-raising 215 mph on the Mulsanne Straight!

Chassis SL76/153

Eric Broadley once remarked about the T70 coupe that “it looked nice and it worked quite well.” That was an understatement. It had been a brilliant car for the privateer. He also said: “The 3B was a natural progression. It was a lot quicker than the Mk3. It had wider tires, better suspension with different geometry, and a better monocoque. It was a better car right through.” Broadley also felt the Aston engine hadn’t worked, and that the Chevy itself wasn’t good enough to bring the best out of the car. It had serious engine reliability problems. Nevertheless, in spite of problems in long-distance races, it did very well in shorter events and sold well.

Lola had produced 15 of the “Mk1” T70 open-monocoque “spyders” (the SL70 cars), and then 33 “Mk2” SL71 chassis open cars before the appearance of the Mk3 coupe, the SL73, of which 21 were made. Next, came the 8 Mk3B “spyders,” a further 6 Mk3 coupes before the introduction of the SL76 Mk3B coupes. These 16 SL76 cars were chassis numbers SL76/138 through SL76/153, the car you see here. Chassis SL76/153 was the very last production T70. There were, some years later, 7 postproduction “continuation cars,” mainly cars built up from spares.

Chassis Sl76/153 had been sold to Swede Jo Bonnier in December 1969. Bonnier, of course, had been and remained a fiercely loyal Lola entrant and driver, until he was killed at Le Mans in 1972 in his T280. Chassis Sl76/153 quickly passed to Brit Terry Croker. It was then entered for the 1970 BOAC 500 at Brands Hatch for Croker and Derek Bell, though it failed to appear. Croker took it to the Nüremberg 200 Interserie race at the Norisring, in late June of 1970, but had oil scavenge problems in practice and did not start. It failed to finish at the Hockenheim Interserie meeting a week later, and in November it was sold to Carlos Avallone in Brazil to be driven by Emerson Fittipaldi’s brother Wilson.

According to T70 historian, John Starkey, Fittipaldi raced the car in the four-race Coppa Brazil in December of 1970 and, though he DNF’ed in two of the races, he did manage to win one and finish 3rd in another. The car subsequently was sold to South Africa, where it lived for a number of years. At some point in time it was crashed in a race there, and Mauro Borella purchased the remains in 1994. The current owner, experienced historic racer Nigel Hulme, bought it in 1996, and it was soon restored by Clive Robinson, and has been racing actively since 1998.

Driving the Mk3B

Not terribly long ago, I had the great good fortune to drive Steven Young’s Mk3B roadster, an ex-Penske Team car from 1967, at the swooping and dangerous Willow Springs circuit in California. Given that this was a track I had never seen before, it ended up being a pretty cautious drive. But back on familiar ground at a BRDC test day at Silverstone, with Nigel Hulme taking turns behind the wheel with a couple of other well-known historic exponents, this was a chance to work a bit harder and get the full feel of what the T70 coupe was all about. I didn’t waste any time.

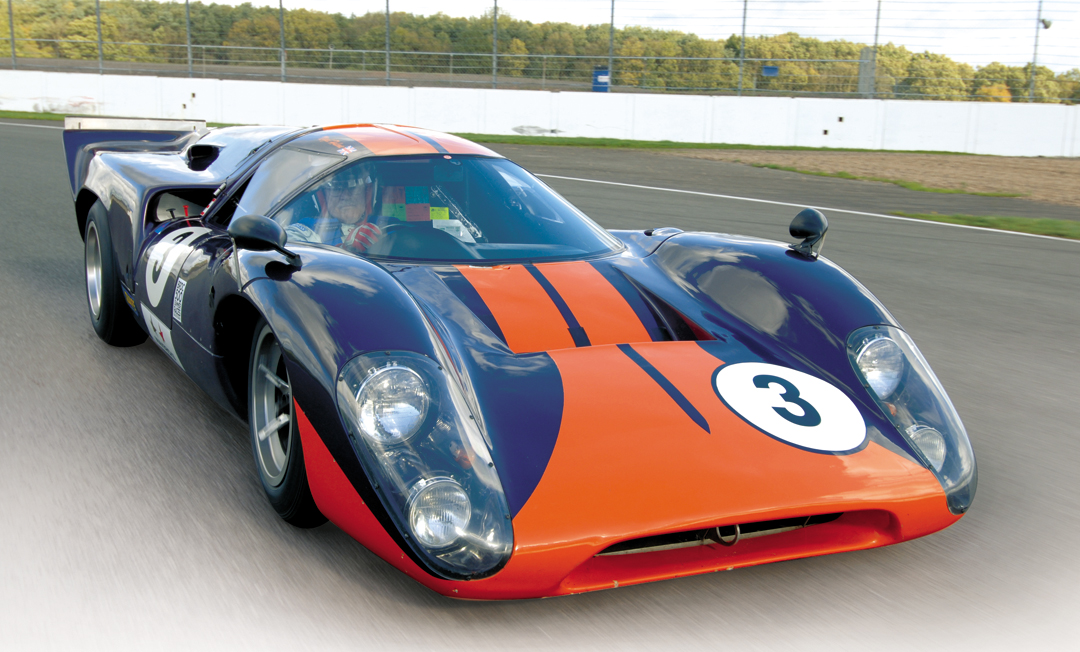

On the run up to this test, I had been looking closely at the range of T70s, both open and closed. While I always loved the striking shape of the coupe, I couldn’t have told you the difference between an Mk3 and a Mk3B, so I had to look closer. First, because Nigel Hulme’s great purple-and-orange beast is so incredibly striking, it’s hard to see the subtleties. But the Mk3B had been re-shaped and the nose was less round than in the earlier car—slightly drooping, flatter, and more purposeful in appearance, with four rather than two headlights. The later nose treatment had altered the location of the radiator, and much attention had been given to better airflow to the radiators, as well as over the body. Broadley was fairly late in coming to the use of lip and tail spoilers, but the Mk3B had them. Hulme explained that the front lip had not been refitted and that might lead to a bit of understeer. There were small spoilers on the rear body section however. Downforce on the Mk3B was much greater than earlier examples, and was quickly noticeable in medium and fast corners. I remember the roadster as having less feel in the corners…this was not the case with this car.

Nigel Hulme’s comment to me as I sucked in my breath and poured myself into the cockpit was that the Lola was “very forgiving, very light to drive, easy to manage at 7/10ths, and a bit less easy to manage at 10/10ths.” I didn’t think I was reading too much into it to think that the objective might be to play around in that 8/10ths–9/10ths region! He had said that people expect the T70 to be heavy, something of a handful, and hard to drive but that it wasn’t. Blasting down the Silverstone pit lane, out into busy test-day traffic, it became immediately clear that Nigel was right. It is also apparent that all of the 505 bhp from the mid-mounted Chevy is on tap and readily available to the driver. This will sound like boasting, but the Lola was, within just a few laps, the fastest car on the circuit. The engine was so surprisingly manageable. When Hulme first had the car, it was finding its peak power at 9,000 rpm, but now it has been refined to do that at 7,200. That makes it quite torquey as well and sends it hurtling out of corners, with the wider power band making it more driveable. The power comes on at 3,500 rpm, with a surge rather than a twitchy burst, and soars to 6,800–7,000. It’s smooth and progressive, and as I sat in the racing seat, trying not to be too awe-struck, I realized I had begun to treat this car like an old Formula Ford of the same period—dive into the corners, allow the backend to slide until you can feel the rear wheels bite and then push the throttle hard. In spite of having 400 horsepower more than my FFord did, it behaved just as well. Mind you, it was soon a lot farther past the top speed of a little single-seater, and the big brake callipers had to work harder to slow it down. But the feel remained similar…you knew everything that was happening. It had been set up for slicks, but was running on intermediates. However, the understeer wasn’t evident, and it seems possible to dial out any minor problems. It just inspired such terrific confidence.

Afterward, I was aware that I hadn’t paid any attention to the interior. The car is shaped around the driver. Static it feels large, but once it’s rolling it gets smaller! Everything works without fuss. The Hewland box was immensely civilized. One of the other drivers thought the brakes were “a little soft” but they were about as good as anything I have ever experienced. The pleasure was in not having to make vast use of them. Into Silverstone’s Copse Corner, it’s a quick touch and power through, first in third gear, but then soon in fourth. With loads of grip, it’s flat out down to Maggotts, brake late, and bang down to third and then second and virtually don’t lift, keeping the revs up as the car swings way out to the left on the exit of the tight right-hander and then it’s flat again down the straight to the complex. The throttle has to be feathered here through the left-right-right and then up the box and pound past the pits again, just seeing 7,000 rpm with all that thunder at the back. No wonder everyone who has one, loves it!

Owning and Maintaining a T70

Photo: Ferret Fotographics

Nigel Hulme has raced this car a great deal since he got it over ten years ago, and that means he has gotten to grips with it, and that it has to be professionally looked after, because it’s a serious racecar, not an occasional machine to take for a spin. It does the South African series now on a regular basis, as well as many other events. During the course of our test, it suddenly decided not to start and some swift but intense work traced this to a relatively minor distributor problem. This took a good knowledge of the 5-liter Chevy engine to eliminate more serious ills. The old head gasket troubles of the ’60s is now long gone, but you have to know what you are doing.

If you want one of these, they are around, but all the owners love them and are hesitant to sell them. Four years ago the prices languished around the $250,000 to $300,000 mark, but now they are up to $500,000 to $600,000. Nigel feels they were always somewhat undervalued compared to GT40s. They have clearly come back in from the cold.

A Legend Continued

Lola Cars have announced a limited production run of new T70 Mk3B chassis eligible for the world’s major historic racing series. While “continuation cars” were at first seen as controversial, strict guidelines have prompted not only Lola but Chaparral and Chevron as well to both move in this direction. The cars are in such demand that the price of £165,000 or roughly $300,000 is being viewed as quite attractive. The cost includes a complete car, with a basic, race-prepared, 5.0-liter carburetted Chevy engine.

The first car will be seen at the UK International Racing Car Show in January 2006. This will be followed by an extensive program of circuit demonstrations in Europe and North America. New owners will benefit from free membership of the Lola Heritage Registry providing online technical bulletins and spares information.

Specifications

Chassis: Light alloy monocoque bonded and riveted providing torsional rigidity of 5000 pound per ft./degree

Track: Front: 57” with 8” rims; 54” with 10 1/2” rims

Wheelbase: 95 inches

Weight: 860 kilos

Engine: Chevrolet V8

Capacity: 304 cubic inches/5-liters

Power: 505 bhp @7200 rpm

Bore and stroke: 4.020 x 3.000

Carburettor: 4 Weber 48 DCOE downdraft

Transmission: Hewland 5 speed

Clutch: Borg and Beck 7 1/4” – triple plate

Wheels: Cast magnesium 15” diameter, width 8” front, 10 1/2” rear, with other sizes used.

Resources

Many thanks to Nigel Hulme and Clive Robinson, and to Glyn Jones and Sam Smith from Lola Cars for helping to arrange this test.

Bamsey, I. Lola T70 V8 Coupes—A Technical Appraisal. Haynes Publishing, UK, 1990.

Starkey, J. Lola T70—The Racing History and Individual Chassis Record. Veloce Publishing, UK, 2002.